ON THE FRONTLINES OF SPAIN by Ivan Dolinsek

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

“The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War”

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks posted and provided links to volunteers.

ON THE FRONTLINES OF SPAIN

Ivan Dolinsek,

Spanija, V2, pp 219-231

With a group of 28 volunteers, most of them Slovenians, I arrived in Paris in October 1936, from the Pas de Calais area (France) where I worked in the coal mines. After a few days of checking and collecting the groups, we leave our belongings and documents in Paris and head for Perpignan. There, the transfer organization is working at full speed. Groups are formed, which are transferred by trucks across the French-Spanish border during the night. I am also in one group. Only before the border do we get passports as Spanish returnees, and so I cross the border under the new name of Juan Ferraro. The night is cold, our teeth are chattering from the winter, but our hearts are warm with impatience to reach the battle site as soon as possible. The next day we arrived in Figueres, where there was a gathering place for volunteers in an old fort. Various languages are heard: French, Czech, Serbo-Croatian, Hungarian, German, Polish, etc., but we are all connected by the common word “compañero” (comrade). We practically already feel like soldiers of the revolution. A few days of rest, and then we are already sitting on the train, which will take us to Barcelona, then Valencia and, finally, to Albacete, the main gathering place of the Interbrigadists. The journey is quite slow, due to the danger of air raids. The train is decorated with Spanish and red flags. Songs are sung in various languages, and the “Internationale” the most, which resounds as if sung in one language, connecting all inflamed hearts. At every station we were met by the people and enthusiastically greeted with “VIVAN LOS INTERNATIONALES”! The Spaniards showered us with flowers and oranges, expressing their hospitality, because they understood that we came to their aid with sincere wishes and a decision to lay down our lives for their just cause.

In Albacete, we are housed in the Salamanca barracks. Checking again, writing out biographies, getting military clothes, weapons and gas masks. Then we were sent to exercises in the nearby town of Tarazona de la Mancha, where the XIIIth Brigade was formed. They assigned us Yugoslavs to the 1st company of the 8th Čapajev battalion.”

Kazimir Krušnjak from Rijeka (former captain of the Yugoslav army, who lived as an emigrant in Paris) was appointed as company commander, and Milan Kalafatić (Nikolaj Nikolajević) as commissar. There were about 46 Yugoslavs, among others: Ivan Krajačić (Stevo Verdić), Vidaković (Kostaluka), Petar Levantin, Ivo Bodlović, Linardo Guberina, Stjepan Prpić, Andrija Černić, Pavao Vrdoljak, Duro Vujović, Mihael Pervina, Jovo Ivanišević, Jozef Kapiš, Franc Sterle, Simon Kranželić, Jožef Kozole and others whose names I no longer remember. Then the Madari {from Madaras Hungary} brothers Varga and three Belarusians, former officers of Imperial Russia, who came to wash away their past (they all died), several Austrians and two Englishmen. At the marches, everyone would sing in their own language. Although there were only two Englishmen, however, they also published their wall newspapers in addition to ours.

After accelerated training, the order came to go to the front. We were all delighted, thinking that we were leaving for Madrid, where the situation was very serious at that time. However, instead of going north, we were directed to the east. When we arrived in Valencia, an honor review was held and speeches were made, and then we were assigned a division of newly arrived Russian tanks, with which we were sent in December 1936 to the Teruel front. The intention was to attract forces from Madrid by attacking Teruel and thereby ease their position.

In a fighting mood, we passed through Valencia on trucks, where the International Brigade songs “Po dolinam i po zgorjam {In the valleys and the mountains}”, “Internationale” and others rang out. Next to us, miserable villages were disappearing, where age-old misery reigned. Clenched fists of peasants were raised everywhere. After Segorbe, a small town, we turned towards the mountains above which the city of Teruel rises.

FIGHTS FOR TERUEL 1936

Somewhere in the middle of December 1936, our offensive on Teruel begins. We surround it from the east, north and west. The “Galan” brigade attacks from the east, our XIIIth brigade from the north, and parts of the anarchists from the west. Hill after hill falls into our hands. The railway to Teruel in the west and the main bridge are cut off. The enemy retreats into the city. We attack up the hill, while the bullets whistle from all sides. Here and there, the wounded or dead fall. In the evening, before our main attack, my company took shelter in a cove under a bridge. In the middle of the cove, hidden from view of the enemy, dinner is being cooked, the smell of which makes our empty stomachs even more hungry. While we sit around in the groves and impatiently expect to eat at least something warm, an explosion and an enemy grenade explodes next to the boiler with dinner. Fortunately, we were quite far away, so there were no losses.

The next day, I think it was December 28, we occupied the main elevation from which the bunkers and the first houses of Teruel were clearly visible. We held the central position. On the left, the road wound towards the city, and on the right was a slope all the way to the railway line. To my left lay Andrija Černić. Bullets whistle around us. At the end of the road, up at the top and slightly to the left, you can see an enemy fortification from which a heavy machine gun is firing. When I looked a little closer, I noticed the head of a Moroccan. “Do you see that Moroccan?” I spoke to Andrija, but he didn’t answer. I turned and looked: he buried his face in the ground, and a hole can be seen on the French helmet, right on his forehead. He was hit by a Moroccan sniper. Poor Andrija, as if he had a premonition, because a few hours ago he told us: “If I fall, don’t forget my wife and two children back home”.

UNDER THE BODY OF AN UNKNOWN DEAD

The command arrives to attack the enemy’s stronghold behind the Russian tanks, from where the heavy machine gun is mowing down our ranks. Pero Levantin and I each got bags with six hand grenades, and I also got a red flag to signal how far we had come. Soon, two Russian tanks appeared on the left side of the road, pounding the enemy’s positions with cannons and machine guns. When the tanks reached our height, we jumped out of cover and ran, I after the first tank and Levantin after the second tank.

Protected in this way, we arrived right in front of the enemy’s stronghold. When the tanks started to turn around to go back for new ammunition, I jumped into the ditch next to the road and immediately threw hand grenades, one after the other, at the enemy fortification. The machine gun fell silent. However, when I looked back, I saw that I had gone too far. So lying in the ditch, sheltered on the left side by an embankment, in front by a tree, and on the right by a slope, I raised and waved a red flag to indicate to our men how far I had come. Suddenly, my right arm goes limp. I felt a sharp pain and blood started soaking the sleeve of my overcoat. The bullet pierced my right arm.

The enemy inserted a new crew into the stronghold and reinforced the fire. The bullets poured like rain, especially from the exposed right side. I was about 50 meters from the enemy, closer to him than to us. I controlled myself not to jump from the stronghold, and I am afraid of being captured. With my left hand, I felt in my bag for another hand grenade. I activated it with my teeth, determined to pay dearly for my life. Yet they did not dare to go out, because our rear also pressed with fire. When I looked to the left, I noticed the body of an International Brigades soldier at arm’s length above me. I pull him by his coat, and he rolls right on top of me. He too was hit right in the forehead. So cover me with your body. Clinging to the gully, and sheltered from the front by a tree, I listened to the bullets smacking against my dead protector.

This lasted almost the entire afternoon. Fortunately, it was quite cold that December day, so my blood clotted. Although I felt the weight of the dead man on my back, he still protected me. Whenever I peeked behind a tree, I could clearly see fez heads in the enemy’s stronghold. Finally, it started to get dark, and the fire started to die down on both sides. I had to think about retreat. I got out from under my dead comrade and started crawling backwards to the tree line by the road. I thought it took forever. I finally heard the voices of my friends in the darkness. When he saw me, Commissioner Kalafatić was surprised: “Well, you’re still alive, and we’d already written you off,” he said and patted me on the shoulder.

We had quite a few losses that day. Company commander Kazimir Krušnjak was killed by a hand grenade. Pavle Vrdoljak, Guberina, Linardo, Ivo Bodlović, Pero Levantin, Petro and others were wounded.

Although the conditions were favorable, this attack did not succeed because the simultaneous attack of the entire battalion was not organized. They took us wounded to a nearby medical center, and then to a village where we waited for the morning on the floor of a shed. When the ambulance arrived, they transferred us to the hospital in Valencia.

IN HOSPITAL

After so many days of dirt and lack of sleep, it was a great blessing to be in a clean bed. However, too soon we rejoiced at the much-desired peace and rest. Somewhere around 10p.m., a long whistling sound was heard, followed by an explosion. I told Pavlo that it would be airplanes, but he said that according to the sound, it would be artillery shells. Where did the artillery come from here, when the front is far away? Suddenly, a powerful explosion shakes the entire hospital. – Well, we didn’t die at the front, but we will die in bed like grandmas – said Pavlo. Later we found out that we were targeted by an enemy cruiser, which approached Valencia under the cover of night. It was a greeting card for the New Year 1937.

Every day they examined us and bandaged us. It’s hard for me to listen to Pavlo’s moans, when he is being swaddled with gauze in the heel wound. My wound on my right hand has festered. A bespectacled doctor after staring for a long time said:

“It would be better to amputate the arm than to have gangrene”.

When some friends, members of the KP, came to visit us Spain, I told my friend Pilar the doctor’s opinion.

“No matter what kind of amputation, I’ll send you our doctor who will fairly heal you.”

And it was like that. Another doctor came and thoroughly cleaned the wound. It was quite painful, but within a few days the wound began to heal and I was soon able to leave the hospital. So, thanks to my friend Pilar, I saved my right hand. Then I found out that among the hospital staff there is an organization called White Aid, which works for the enemy. Its goal is to disable as many of our soldiers as possible.

During my stay in the hospital, I diligently studied Spanish, which, thanks to my knowledge of Italian, I mastered quite quickly. So, in the afternoon I went out with Leventin (who later died on the Ebro) and got to know the city and the people. Everything was new for us. Kindness and hospitality everywhere. As soon as they hear that we are interbrigadists, they invite us and honor us. It is clear that we also got revenge on them. They made sure to offer us the local specialty “La paella Valenciana” (Valencian risotto). Unusual, but very tasty, especially when washed down with good Spanish wine! While the battle against the Fascists was taking place on the front lines, here in the rear there was a struggle for greater production and aid to the front, the fight for ideological and cultural elevation, etc. We read on the banners, “Literacy is freedom, illiteracy is slavery”, “Learning and fighting means freedom”! When the government of the Popular Front came to power, half of the Spanish population was illiterate.

AGAIN IN ALBACETE

Sometime in the second half of January 1937, I returned to Albacete and reported to the personnel department. Since I was still unable to fully squeeze my right fist due to the wound, I was sent to work in the censorship department with Comrade Gustinčić, who managed the organization of mail for the International Brigades. With my knowledge of foreign languages, I was welcomed to him. I knew Italian, German, French, Russian, Spanish and Esperanto, and the press came in various languages. Janhuba, a student from Prague, and Jose Vergan, who delivered mail as a courier and was seen everywhere and eagerly awaited, also worked there.

Due to the conspiratorial nature of the soldiers’ stay, correspondence was quite complicated.

So, for example, I was sending a letter to my aunt to France, that of the Alfreider family in Sušak, and my mother would go there from Rijeka and pick up my letters. In the same way, only in reverse, the letters would reach me. I stayed there for a short time. Already at the end of January 1937, I was invited to the Headquarters of the International Brigades by Comrade Fein (Filipčić), the head of SIM.

Since I kept asking to go back to my unit, I thought that now I will get a rifle again.

“Comrade Ferrara, I called you because I have a special task for you”, explained Fein.

I thought, surely they will send me to the rear of the enemy as a guerilla, like Krajačić, Vujović and others were sent. And that’s what I wanted the most.

However, Fein continued: “You know Spanish and Russian and you will be assigned to work as an interpreter for Soviet advisers.”

When I said that I would rather go to the guerrillas, Fine answered: “This is not about personal wishes, but about the needs of war. And that is a confidential duty and a party task, so there is no discussion about it.”

I was a little disappointed. I was reassigned the same day to the Soviet headquarters and assigned to a Russian colonel, who had to work on anti-aircraft protection on the entire Republican territory.

At that time, anti-aircraft weapons arrived from the USSR: cannons (80 mm), searchlights and listening devices. They immediately started with the training, which was very short, but successful, because the battery crews and officers were chosen from among the Spanish artillerymen. It was the most difficult for me, because until then I had never dealt with cannons, and even less with artillery terminology. However, with good will, studying day and night, I overcame that too.

IN DEFENSE OF MADRID

At the beginning of February 1937, we left with two batteries for Madrid, which suffered the most from enemy aviation. We arrived around 3 o’clock at night and immediately reported to the headquarters for the defense of Madrid. General Miaja, defender of Madrid, was unusually happy about our arrival, as was Jose Dias, general secretary of the KP of Spain. The observation post is placed on the telephone switchboard, the tallest building in Madrid {the Telephonica}. One battery is deployed in the suburbs of Puente Vallecas, and the other on Cuatros Vientos, so that they can protect the skies of Madrid with cross fire.

At 7 o’clock in the morning, the batteries were already dug in, camouflaged and ready for action. From a distance came the rattling of machine gun fire and explosions in the Carabanchel and Casa del Campo sectors. The weather was cold, and thin snow covered the streets and roofs. I was in the 11th Battery, located in the square of the suburb of Vallecas, surrounded by small houses. I was impatiently waiting for the arrival of the plane. The artillerymen were shivering from the cold and cutting wooden sticks, which, due to the strong air pressure when firing the cannons, they held between their teeth to protect the eardrums with their mouths half-open. Due to the frequent loss of these sticks, fighters tied them around their necks.

Around 8 o’clock in the morning, the first 6 “Junkers” appeared. They were flying at an altitude of about 1,500 m. We were given shooting coordinates. Commands for height, distance, speed were also applied, and then “fire!” echoed. The cannons roared, and the windows of the surrounding buildings were blown out. In the sky, in front of a group of enemy planes, white clouds from the explosion of shells are getting louder. They did not expect such a welcome, so they immediately started to gain altitude. We made a correction and then fell again! We hit right in the middle of the flying formation. One Junker burns and falls. The fighters are delighted with their first baptism of fire and their first success.

The brazen raiding in the sky of Madrid and the unpunished bombing of that brave city where women and children suffered the most have stopped. The remaining planes dropped bombs at random and disappeared. Our fighters also appeared over the skies of Madrid, who daily and courageously fought against ten-fold superior enemy forces. The population of Madrid daily followed the battles between “Messerschmitt” and “Fiat” on the one hand, and Russian “Chatos” and some old fighters of the French squadron on the other, and applauded every victory of our fighters.

Due to the small number of field cannons of the Republican artillery in that sector, we were tasked to shoot at the enemy positions on Carabanchel, where the enemy’s pressure was greatest.

The defense of Madrid succeeded, and the enemy was stopped. Trench warfare is gradually turning into underground warfare. Our miners dug a tunnel under the enemy positions and blew up houses with Fascists. They responded to this by attacking the buildings of the University City, which was defended by our troops, with flamethrowers. Basically, the battle for Madrid was winding down, and so was the aerial bombardment. The enemy limited himself to pounding the city with Polish artillery. Despite the government’s strict order to evacuate the non-combatant population of Madrid, it did not comply. It bravely and heroically endured all the hardships of the war: bombing, food shortages, etc. As early as 2 o’clock after midnight, queues would start in front of shops for rationed food. Each one patiently, sitting on a small table, waited for his turn. It was not uncommon for a shell to fall among them and blow them to pieces. And yet they would rather die in Madrid than agree to leave their city. By doing so, they proved their faith in their Republican government and army.

During that time, I was promoted to the rank of sergeant and served as the political delegate of the 11th anti-aircraft battery.

IN GUADALAJARA

After their failure at Madrid and in the offensive on Jarama, where they were held in February 1937, the enemy was preparing an offensive on Guadalajara. In March 1937, our battery was sent to Alcala de Henares, to protect the gathering of our forces.

In March 1937, the Fascists struck from the northeast through Guadalajara. About 40,000 Italian soldiers and about 20,000 Legionnaires, Moroccans and Phalangists under the command of General Roata participated. After a short initial success, the enemy was stopped, and the Republican forces went on a counter-offensive. The enemy was beaten and forced to flee. Italian motorized and mechanized units suffered a particularly heavy defeat.

The Garibaldi International Brigade also played a prominent role in these March battles. In the 11th Division, under the command of Lister, the XIth and XIIth International Brigades, in which there were also Yugoslavs, participated. they shouted: “Guadalajara no es Abisinia…”(Guadalajara is not Abyssinia…) And our two anti-aircraft batteries, which were placed near the front lines, were effective not only against enemy planes, but also beat targets on the ground.

In the south, Malaga fell, and enemy forces advanced towards Almeria. In order to protect this port and the city, as well as the refugees from the south who were mercilessly pursued and machine-gunned by enemy aviation, anti-aircraft batteries were also sent there. And there the enemy (Italians) were stopped, so that only his aviation continued its activity. However, on May 31, 1937, there was an attack on Almeria from the German cruiser “Deutschland”, which bombarded the city and the port with all its guns, destroying a large part of it. Over two days, the city was covered in thick smoke and dust, dead and wounded. When the situation calmed down, we were sent north again, to Madrid, and then we were transferred to Valencia to protect the city. During the lull on the fronts, the enemy attacked the cities with aviation, in order to break the resistance of the Spanish people.

The anti-aircraft defense did not have sufficient weapons to defend such a large territory of the Republic. There were only seven heavier anti-aircraft batteries, of which two were old and stationary – one in Cartagena (military port) and one in Barcelona and five mobile Russian batteries: 11, 12, 13 and 14 with Spanish crews and the 15th battery, “Gottwald” with International Brigadists (Czechs, Germans and some Yugoslavs). In addition, there were several lighter anti-aircraft batteries of 20 mm type “Oerlikon” of Swiss origin, which were mainly used to defend heavy batteries from airplanes in low flight. Sometimes, in extremely difficult situations, these batteries were also used to fight against tanks. There were also some four-barreled anti-aircraft machine guns, mounted on trucks, which served to defend the infantry on the march and in position. There were few searchlights and devices for eavesdropping and detection of the enemy, mostly concentrated in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia. Due to such a shortage of anti-aircraft weapons, we were forced to constantly transfer batteries from one end of Spain to the other, to change the positions of guns almost daily, either for combat needs, or to create the impression that we had a larger number of weapons at our disposal. We often changed positions so that bombers or artillery would not destroy our batteries. We usually operated during the day, and at night we moved to a new position, dug trenches around the guns again and camouflaged them. And so, from day to day, which greatly exhausted the fighters, who often envied the infantry. At least they could rest during the lull. Only the rains, which are rare in Spain, allowed us to rest and sleep, even in the mud.

ON THE BRUNETE FRONT

When the offensive of our forces began in the Brunete sector in July 1937, our 11th and 15th “Gottwald” batteries were also transferred to that sector. The fighting was very difficult and bitter. The enemy aviation completely dominated and almost continuously machine-gunned and bombarded the positions of our units. From the July heat on that karst terrain, the explosions of airplane bombs and artillery shells, it was like hell. Enemy aviation focused especially on our anti-aircraft batteries. Suddenly, there was an attack from all four sides by planes in divebombing. The order was given for each cannon to fire on its own side, directly without the use of devices. A real hell broke out. Suddenly a terrible explosion and flash, then darkness and silence. When I after some time regained consciousness, I saw that I was lying in the bushes of a small valley, almost 30 meters from the battery. I hear the sound of the plane. I open my eyes. I can see with one, the other is filled with blood, which flows down the forehead. So, I’m still alive after all! I feel dazed and beat up. My chest is bleeding on the left side. I try to get up, but then I notice that my left leg is also bleeding. I was wounded in the head, chest and leg, and also quite contused. I call for help and soon two friends arrive with a stretcher and take me to the changing room. The bomb fell in the middle of the battery and killed half the crew. Of the four cannons, three were overturned, the ammunition ignited.

A machine gun set up for anti-aircraft combat

A rather large group of wounded was waiting at the dressing station. Finally, I was also bandaged and put in the ambulance. I lost consciousness again. I just woke up in a Madrid hospital bed. Thanks to the good care and procedure of the hospital staff, as well as the visits of the girl from Madrid, Pilar, my condition quickly improved. After a little more than three weeks, I left the hospital at my own request, although not completely cured, and reported to my headquarters in Madrid. I was assigned to the headquarters of the anti-aircraft defense division with Russian advisers. I was a liaison officer with the rank of captain. During the day I was at the battle positions of the batteries, and at night I maintained contact with the headquarters.

ON THE ARAGON FRONT

In the Zaragoza offensive, which began at the end of August 1937, our troops broke through the enemy’s wide front and occupied Quinto, Belchite and some other smaller places. The Yugoslavs from the “Daković” battalion, who were the first to capture Quinto, stood out in particular. Our two batteries shot down several enemy planes. New twin-engine Russian bombers also appeared and bombarded the enemy positions. I watched the shells of the German anti-aircraft batteries explode far behind our planes. “Look, look, they shoot worse than us,” remarks Captain Hernandez, the commander of our battery. The Poles penetrated farthest from us. They could see Zaragoza with the naked eye.

However, despite very nice initial successes, the enemy managed to stop our further penetration. The front becomes somewhat stabilized such a situation – the trench warfare with smaller units lasted until the end of September 1937, when it completely calmed down. Here we suffered a lot from the heat. Over 40°C, and nowhere cool. No trees, only sand and some dry soil, and no water for medicine. It is not for nothing that the Spaniards call Aragon the Sahara of Spain. Water was brought to us by tankers and distributed only one liter for the whole day – for drinking, washing and shaving. We dipped the handkerchiefs in a glass of water enough to remove the sweat.

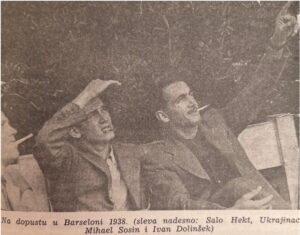

On leave in Barcelona in 1938 (from left to right: Salo Hecht, Ukrainian Mikail Sosin and Ivan Dolinšek)

One day we shot down a “Junker.” I was assigned to escort a captured German pilot, who had saved himself by parachute, to the Divisional Headquarters. We were both almost killed by enraged fighters. They wanted to liquidate him, I barely protected him with a gun in my hand. It was severely forbidden to kill officers, especially captured pilots, because we later exchanged them for our own. I barely managed to get him to the car and take him to Headquarters.

Looking at his burned and wounded face, I asked why did he come here to bomb innocent people. He shouted: “I have come to fight against Bolshevism!” I was seething with anger, but I had to restrain myself.

We left for Barcelona, which is bombarded more and more frequently by Italian Savoys and German Messerschmitts from the island of Mallorca. Here, for the first time, we had a carpet bombardment, so they tear down one neighborhood after another.

We stayed in Barcelona until December 1937, and then we were transferred to Tortosa. We had to defend that critical point, because our troops attacked Teruel again, which they captured in January 1938 despite the severe winter and enemy resistance. But, in February 1938, the enemy recaptured that place and then launched an offensive towards the sea with strong forces. Despite our fierce defense, the enemy managed to penetrate to Tortosa and cut the Republican territory in two.

OFFENSIVE ON THE EBRO

At the end of July 1938, the Republican offensive began on the lower course of the Ebro River. Our side broke through the enemy’s defenses, crossed the river at Mora de Ebro and penetrate deep into the enemy’s rear. But they were stopped there. The fighting in that sector lasted with alternating success until November 1938, when the enemy broke through the front with strong forces and began an advance towards Barcelona.

At Caspe there was such a mixture that it was no longer known where our men were and where the enemy were. When I sought out the General Staff for further instructions on battery position changes, I was told, “Well, your battery is surrounded.”

I managed to break through the enemy lines at night and reach the battery, but it was good luck they were not yet aware of the situation. However, at night we managed to take a detour to get the battery to Gerona. Because of this, I was awarded a medal for bravery at the General Headquarters in Lerida, where I learned about the withdrawal of the International Brigades from the front.

Even though I was the only foreigner among the Spaniards, I was still recommended to retire. So in December 1938, I said goodbye to my war comrades and went to Barcelona with my chauffeur, Joaquin. We kissed and I gave him my Astra pistol as a souvenir. Despite the difficult military situation, a large farewell meeting for the International Brigadistas was organized in Barcelona. The Spaniards said goodbye to their comrades with sad hearts, decorating us with flowers. Above the speaker’s stand, it was written: “Spain will always be your homeland”.

We were directed to Calella, on the sea coast, the gathering place for the repatriation of members of the International Brigades. There we were accommodated in private houses, where the family welcomed us as their own. Despite the difficulties in eating, they shared the last morsels with us. Here we were given commemorative diplomas for our participation in the Spanish war. From here we were taken to Ripoll and Llers near Figueres, and then to a small fishing village near the French border, San Pedro de Pescador.

The president of Mexico Cardenas approved the entry into Mexico of International Brigadists from Fascist countries, who could not return to their homes. A boat was also chartered, which was waiting for us in the French port of La Rochelle. We were placed on the train, but after endless waiting, the French reaction succeeded in preventing us from crossing the French territory and we returned to our earlier place. At that time, the Fascists reached Barcelona and, at our request, we are allowed to return to the front to protect the retreat of the people towards the border. We are forming the Balkan Battalion, to which all those who are able have volunteered.

In this nightmare and uncertainty came the order to leave for Figueres and towards the French border. We arrived there on foot, in the rain, just after the heavy bombardment of the fascist aviation, which was constantly pounding the retreating troops and people. There was a real chaos of fire, ruins and mutilated corpses, especially women and children, who did not manage to take shelter in time. A terrible sight! Barely clothed, hungry, wounded and exhausted, we retreated in the February winter before the enraged enemy. Endless columns of Spanish refugees, with too cold and hungry children and with the remaining bundles of their poor, moved towards the French border. Here and there they would stop and build fires to warm themselves, and prepare something to eat from the killed mule. Finally, we arrive at the French border, where everything has stopped. It was closed. The mass of people anxiously waited for it to open, because the enemy fire was getting closer and closer. Finally, after they took away our remaining weapons, we crossed the French border on February 10, 1939. A flood of over 500,000 refugees; fighters, women, children, old people, cold, starving and exhausted descended down the slopes of the Pyrenees and headed to the French concentration camps under the escort of gendarmes.

Ivan DOLINŠEK