LEAVES FROM THE DIARY OF ONE WHO IS NO LONGER THERE by Ales Bebler

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks made several minor edits and added additional footnotes for clarity.

LEAVES FROM THE DIARY OF ONE WHO IS NO LONGER THERE

Spanija, Volume 3, pp 26-44

The column climbs the hill one by one. These are the last slopes of the Pyrenees on the Mediterranean side. We are still on French territory and approaching the Spanish border.

Each of us is up to the last stage, the small fisherman’s wharf at Sète, arrived in his own way. However, most of them were sent here by the center for collecting volunteers, organized with the help of French trade unions in Paris. My group, five Yugoslavs, political émigrés, with about twenty other unknown comrades, soon after arriving in Sète, were loaded into a fishing boat and hidden in its bottom. But, after several hours of waiting, we disembarked again. The owner of the boat changed his mind. We had to take refuge in the surroundings, with peasants, winegrowers, who were organized by the Communist Party of France for this type of assistance to Republican Spain. After a few days, in the middle of the night, a large number of volunteers from various hiding places gathered again. On the main road, near our villages, we came across a line of buses. In them we move towards the border. We pass through the town of Perpignan. The gendarmes at the intersections don’t seem to be surprised and don’t stop us. The government of the Popular Front, the government of Leon Blum, does not strictly adhere to the agreement on non-interference in the Spanish Civil War. Its internal affairs bodies in the border nom region they close their eyes. At least in this sector even in those days.

The road climbs and at one bend, the line of buses stops. This is where the hike begins.

I have been sitting in a French prison for the last few months. The police found me in Paris without documents, but they identified me. The court convicted me of a violation of the individual decree by which, many years ago, I was deprived of the right to reside in France and expelled from that country. The decree was personally signed by Pierre Laval as the Minister of the Interior. I became very weak in prison. The food was insufficient and desperately bad. And now to climb the slopes of the Pyrenees for hours! I carry a couple of cans and a large scope in my backpack. I “invested” my last money in with the assurance that they are well spent. In addition to myself, here, but also this material aid to the Spanish Republicans. But in my “condition “, even that small load is heavy for me. I can barely move. Every step uphill is a pain. My heart is pounding so I can hear it and feel it painfully. However, when you have to, it’s not difficult, as they say in our country.

We did not know where and when we crossed the border. I guess somewhere where the path turned to the other side. At dawn, we descend, and in front of us is a new column of cars. The drivers speak Spanish. So here we are in Spain!

Figueres awaits. Barrack life. Blankets and portions, here getting up with a trumpet, a cauldron and many other things reminiscent of military service.

Mass of volunteers from all over Europe. Some are from America. They are students. And from Europe, the majority are industrial and agricultural workers. Many semi-literate people who ask us to translate for them from one language to another, to write letters to relatives for them. A few Germans, fugitives from Hitler’s “paradise”.

The train has just left Figueres station. It is full of volunteers. It’s morning. March, 1937. We are talking in the compartment in European languages. It’s cold, and in the heart. Through Figueres we have just marched on, but the city seems to be dead. To the front let’s go, and the streets are empty?! Maybe it’s too early, maybe people they are still sleeping, maybe they haven’t been informed about our arrival? Where is he going? maybe? What awaits us? Spain, do you want our help? We brought you your life, and you seem to be indifferent!

The sun is starting to warm up. Cypress trees, olive trees, houses with red roofs. It’s getting brighter, warmer on the train, guys louder. Suddenly the train stopped. Here we are, at a station in the middle of a larger village. There are many people here. Girls with flowers, blushing faces. They shake our hands. They offer us oranges from large baskets. Whistle. The train should leave. The girls shake oranges out of the train windows. The whole floor is covered with oranges. Exclamations, song. We climbed onto the benches and waved to the girls through the windows as the train left.

Spain, the working, peasant worker, met us for the first time and hugged us.

Albacete, a larger town. It is the main base of the International Brigades. Guys are lying on the floor in the barracks. Some already have aprons, some are uniformed. They line up in the yard. Some exercises are starting. The streets are full of people. They are mostly Internationals. Those who already have weapons are on the trucks, and they are probably going north, towards Madrid, to the front.

I was walking in that crowd, when suddenly a small car stopped in front of me. Next to the driver sits an officer with a familiar face. This is Vlajko Begović. We said hello. And when they found out that I had just arrived and that I hadn’t even found my way around yet, he said: “If you want to be at the front in a few hours, get in my car.”

What is there to think about such an offer? Begovic came from the XVth brigade from the Jarama front, where the brigade had heavy losses and is looking for reinforcements. He quickly completed the formalities at the base headquarters.

*

Front on the Jarama in the vicinity of Madrid, south of it. The Fascist attack was stopped here when, a month ago, the Fascists tried to bypass Madrid and surround it from all sides. Our men stopped them on hills covered with olive trees. There was a big battle here, in which many of our people disappeared, and many were seriously wounded. Veljko Vlahović was also wounded there. The rest dug trenches in the olive groves, buried themselves in the ground. Olive trees all around. But these are no longer olives either. Their foliage was torn from the shower of grenades and bullets, so their branches stick out towards the sky like the hands of wounded men calling for help.

The air is unbearable. Between our trenches and the Fascist trenches lie unburied corpses, dead horses and mules. Above them, millions of flies and flocks of crows.

The XVth International Brigade is in the trenches. They say that there are 22 nationalities in it. All languages are heard here. Some battalions have a national character: French, English, American. There is also the “Dimitrov” battalion. Yugoslavs, Bulgarians and Czechs are in this Battalion. The first company is Yugoslav. There are Yugoslavs from all over our country: students who came from Prague, Croats – woodworkers and forest workers from Canada, Slovenian miners. from northern France.

The brigade commander is a Yugoslav, old communist Vladimir Copić.

In the trenches – silence. Only in the evening, sometimes, a quiet song can be heard. At night, scouts come out of the trenches in the direction of the Fascist trenches and return with information. And it happens that someone on the other side defected to us. Spanish worker, peasant boy. Once an Arab, a Moroccan.

I remember, it was a hot, steamy afternoon. I was approaching the position of the English Battalion along the path. There I met a guy with blond hair. I thought he was English. I asked him where his battalion was. He doesn’t understand English. He must be French, I thought. I asked him in French. That works, but his accent is, it seems to me, German. Okay, I’ll try German. He speaks German. But it seems to me with a Czech accent. — “Are you Czech?” I asked him. “No,” he says, “a Yugoslav.” — “And where are you from, brother?” “From Slovenia!” It was Rudi Janhuba.

In the evening, sometimes the front comes alive. Who knows what the reason is. Real or imagined reconnaissance? A shot of some guard in the bush because it looked like something was moving in it. From one shot on one side, there are five or ten on the other. Ten from the other, hundred from this one. And so, suddenly the whole front is on fire. Rockets are thrown from both sides. Everyone expects an attack. It’s as if two lions are roaring, preparing for battle. After an hour or two, the front calms down.

Our armament is weak. We all have rifles, but there is little ammunition and few hand grenades. The machine gun is our weakness. Only a few per battalion, and they are old, mostly of the “Maxim” type, from the time of the First World War, and they are forever broken.

In the Brigade Commissariat, we also deal with propaganda for those on the other side. We found several megaphones in Madrid. At night, small groups of volunteers crawl out of the trenches in the direction of unfriendly positions and mount megaphones in the bushes or on olive trees. Through them we speak to those there, we explain to them what the war is about, we invite them to come to us. We often provoke the fire of Fascist machine guns. But the success is still near, and the number of people defecting to us is on the rise.

In the larger village behind the front, Perales de Tajuña, we organized a course for non-commissioned officers. The village welcomed pleasant and well-disciplined young men. They are worshiped, sewn and washed in all houses. The peasants are for the Republic, it gave them land, not the landowner’s. One part of that land was turned into another. The girls’ brigade – the men are in the army, they go to the front early in the morning with a song to work. The month of June. The first harvest on the cooperative land begins!

Most of the course participants are young people, almost boys. They are chosen according to their performance in the great battle of Jarama. Great guys. From Yugoslavia, among them is the Slovenian Franz Rozman, in our war “Commander Stane”. A former baker’s assistant, with several grades of elementary school, and now, he studies military science in a foreign language! He works day and night, writes Spanish words in a notebook, which he always keeps in his pocket. During lectures, he regularly sits in the first bench. His blue eyes shine, his forehead is wrinkled with tension. He swallows every word. He wants to understand everything, he has to understand everything.

The best soldiers from the neighboring Spanish brigade also came to the course. There are also anarchists among them. But at school they get along well with our men and love to learn. The officers, Spaniards, are mostly members of the Republican Party. Among them is Captain Garcia, whom we called “Garcia Orden Serado”, which means “Garcia, marching machine”. He was a Guardia Civil non-commissioned officer. Like all the old Spanish army, it never went to war. The only thing he could teach the students were exercises in the marching machine. And that became his specialty. But he is also burning with the desire to learn to fight, which is why he became very friendly with a French non-commissioned officer, an older man and an old Roman warrior with the false name of Perat. That man, who knows what stupidity he did in his youth, served in the Foreign Legion for 25 years. In the end – he often says in conversation, I still fight with my heart, for something that is worth it. The old fox was a master of exercises in the machine gun, to use, to advance from cover to cover and to retreat, to use hand grenades and for hand-to-hand combat.

There is also an old cook, an Irishman. We just call him John. In the Irish uprising during the First World War, he lost one eye. After the defeat, he served ten years in prison. He is without a wife and without children. He is close to sixty years old.

John came to me one day, pulled me away from the others to tell me something. He would like to get married, and he has found a wife. “Help me,” he said. I asked him if it was about obtaining a certificate that he was not already married in his country? “No,” said John, “it’s more difficult.” “What then? Do her relatives get in the way?” “No, what kind of relatives. She doesn’t have any relatives. She is no longer young. She is a widow, she is fifty years old. The children have grown up and they have left her.” “Then what’s the problem?” “A big problem,” said John. “The thing is, she won’t marry me. And you are the Commissar, you speak so beautifully, you could convince her”!

*

Madrid. – Sometimes I have to go there for contact with the Commissariat of the International Brigades. Life in that city cannot be compared with anything. The front is in the suburbs, in the university town. Shooting is heard from there. Sometimes the artillery also comes into the city. And, it seems, people are used to that. There are wounded, dead. An ambulance appears, which takes them away and life goes on. Even cafes and cinemas are full. Children are the only things that don’t exist. They were evacuated.

There are posters on the walls: “Evacuate!” Every morning at a certain time, in a certain place, buses are waiting. Meanwhile, those who have not evacuated until now are used to this life and stay. Everyone tells stories about the great battle, when the front stopped here last fall. Then the whole city started to fight. Battalions were formed according to the professions of tram drivers, textile workers, bakers, waiters. And they went to the front with one rifle for five fighters. And they stopped the Fascists at the approaches to the city.

It’s quiet now. A calm before a new storm. What will this storm be like? In Velasquez Street there is a large house that we call Casa Velasquez (Velasquez House). It houses the Commissariat of the International Brigades. Here I meet Italians: Luigi Longo and Pietro Nenni. Our Central Committee member Blagoje Parović also works there. At his place, we, Yugoslavs, gather and talk about the war, about the relations of the great powers towards it, about our country and about our movement.

Parović – we call him Smith, he is a kind man, warm, kind and often sad. We know that he had problems in the Party and that he is now not happy to be appointed to a position outside the army itself. He obviously wants to be with us all the time and not just visit us when we are at the front or gather us here, behind the front. That’s why we could, a little later, imagine his joy, when he was appointed Commissar of the XIIIth brigade, right before our first major offensive.

Casa Velasquez organizes radio broadcasts in all languages. And in Slovenian. That will be my task for a while, sometimes not daily. In the evening, on the day of the show, we climb up to the top floor of the radio station. Upstairs, that means the sixth, highest floor. Once we had just climbed up, the artillery fire started, shells falling quite close. Each falls a little closer to the radio station. Maybe they want to destroy it. We are about to enter the announcer’s room when a shell falls so close that the windows shake. I looked at the Spanish present and silently we agreed that we will work as long as we can. Until it falls on us, we will tell the world about our struggle.

*

July 1937. The new government, the government of Juan Negrin, launched its first major offensive. We are coming down from the Jarama slopes in convoys of trucks, we start at night, with dimmed headlights, towards Madrid, around it and before morning we arrive under the Sierra de Guadarama Hill. We camp there in the meadows by the river of the same name. The river is warm and clean. It falls over weathered rocks, making small pools. The whole brigade is fighting. There are many new faces. Many new Yugoslavs, including Slovenians. We get permission to form a Slovenian company, and yes- we name it the “Ivan Cankar Company”.

On the second day, the fascists noticed a sudden concentration. Italian “Caproni” formations, appear above the camp heavy bombers. Bombs fall on the camp. After the attack, we first see the wounded, we bury the dead. We also buried the former chief of staff of the brigade, an Englishman, Nathan.[i]

On the third day, at dawn, the movement and operation begins. We go down the steep slope and go across the pasture towards the village of Villanueva de la Cañada. There will be the first battle.

The village, like all Spanish villages, all made of stone, surrounded by quite high stone fences, appears at the end of the plain. The sun rises and the heat rises. The boys are throwing away unnecessary burdens, especially gas masks. They do not believe that Fascists will use gas. Sometimes he throws away a blanket and a steel helmet. The terrain for hiking is getting worse. The plain is criss-crossed by ravines, dried-up streambeds. Connections between units are lost. The plan of attack, so simple on paper, as it was shown to us the night before, is no longer clear to us. The new Chief of Staff collects scattered groups of fighters in the ravines. We “charge” with him to the glade. But there are no enemies there. No one shoots at us and we have no one to beat. We enter a new ravine. The Sun is at its peak. Someone figured out how to get to the water. He dug a hole in the sand at the ravine bottom and got hold of the water. He drinks through a straw. Many follow his example. Contact is established with other groups and the order to move comes from the headquarters. Several battalions bypass the village. In the evening, we attack the village, from all sides at once. A short fight for the first few houses. The Fascists surrender first. We send the columns of prisoners to the rear.

Except at these established points, the resistance is weak. A surprise for the eyes. Maybe we’ll succeed in this whole operation. Its goal, as we now understand, is to relieve Madrid, for our army to attack from behind the Fascist front in the University City in front of Madrid.

On the same day, another brigade occupied the town of Brunete. After that, the offensive was later called the Brunete Offensive. The town of Villanueva del Castillo was also occupied. Columns of prisoners move from there past us towards the rear. Our casualties are not great, but we learn that Blagoje Parović has fallen as the Commissar of the neighboring XIIIth brigade.

At the heights, where we arrived on the third day, we encounter a greater resistance. We dig in. During the night, Fascist artillery shoots at us. And we are so exhausted that no one even moves if a shell fell near him.

I fell asleep by the side of the road wrapped in a blanket. There is a bridge over the river nearby. Fascist artillery is pounding that bridge. The shell fell so close to me that the earth and sand covered my head. Without opening the blanket, I turn on my elbows and descend like a roller down the slope, a little further from the bridge. Isn’t there water? No, it’s a dry field. And fell asleep again.

On the third and fourth day it is even more difficult. On the fifth day, hell begins. Fascist aviation concentrated on our sector. And there are very few of our planes. We count: one of plane of ours to ten of theirs. Later when taking up new positions, I was wounded in the right leg. It hurt as if someone had hit me with a whip. They bandage me, put me in an ambulance. Soon we hope to live in a small villa converted into a temporary hospital behind the front. The next day, while dressing the wound, I noticed that the bleeding had stopped. The leg is stronger. I can stand on it. I jump into the truck and I’m going back to the front. I can hardly find my brigade. What’s more and it is not a brigade. These are the remnants of the brigade, incapable of a new attack. Under the olive trees by the road – dead comrades. Air formations are flying over us every hour, dropping bombs and firing machine guns. Sometimes one of our smaller units or its remnant retreats without a plan and permission, so the others bring it back. The whole front retreats.

On the tenth day of the battle, the remains of our brigade were replaced by a fresh unit – a brigade of Italian volunteers. But the fight is over, and without success.

Will Europe allow Franco and his associates Hitler and Mussolini to win? Or will they also give us weapons? That’s the question the fighters are asking as we retreat in the trucks to the deeper rear.

Towards the end of August, new big movements begin.

We boarded the trains, traveled via Valencia along the coast to the north, then through the Ebro valley to the province of Aragon. The target of the second offensive of Negrin’s government is the major traffic center of Saragosa, the capital of Aragon.

Our train stopped in the middle of a vineyard. The grapes are ripe. The boys jumped off the train and grabbed the bunches. And I, the Commissar, have to keep order, so I call them back. I warn them that the grapes are not theirs, that they have no rights, that they have no permits. But here, two peasants emerge from the vineyard and shout at me: “Leave them, Commissar! Maybe they see grapes and sun for the last time!”

This time, the offensive seems to be better prepared and thought out. We are also better armed. We have quite a few automatic weapons of Soviet origin. We like the “Degtyaryov” machine guns a lot. We also have new anti-tank artillery. They say it’s Czech.

We concentrate and organize for several days. They replenish our food supplies, we buy in the villages what we don’t have enough of. In one village we buy “albardes”, wooden saddles, for mules. Peasants, all old men and women. All the male youth are in the army, and the girls are mobilized to help the army in the offensive. People are ready to give us everything we need. Brand new, just out of the printing press, money with which we pay albardes, they take it as exchange. Many no longer believe in the value of that money or in the victory of the Republic. It’s hard for them. They are sad.

On the third day, our Brigade approaches the fortified town of Quinto. We attack the first outer bunkers. Bloody bloody onslaught! I found myself in the place where the Fascist machine guns were mowing our Yugoslavs down. There lies the commander of our company, Mijat Masković, bloodied, gray-pale face. He’s a wonderful, big guy, with a beautiful determined face, thick black hair. Someone has already closed his eyes. There also lies Sapir, a Lithuanian, an officer in the Brigade headquarters.[ii] He advanced with us. The survivors gather. The new commander, Peko Dapčević, counts them.

I find out that a Spanish company attacked to the right of ours and lost all its officers. They all charged at the head of the company. Major Chapayev [Mihaly Szalvay], a Hungarian, takes command of the company and asks me to take over as temporary commander of that company. I gladly accept.

We enter the town. Here is the church. Like most Spanish churches, this one is a real fortress. They are shooting at us from it. We shoot at church windows. We’re bringing in an anti-tank small gun. We punch holes in the church tower with it. A white scarf is shown on a window. Surrender. A dozen Falangists, mostly wounded, leaves through the window. We send them to the rear. Where are the other Fascists? The town is all stone. Every house is fortified. There are sandbags on some windows: machine gun nests! One street seems suitable for a maneuver, to bypass the center of the town on the left. With the rifle unholstered, I start walking along the sidewalk on the other side of the street, which seems to me to be safer from possible fire. I am approaching the corner of a wider, probably the central street. Far away, about fifty meters behind me, are two of our Spaniards. Suddenly, a soldier appeared in front of me. I can see the Fascist tag on the shirt. We met face to face. We look at each other confused and surprised.

I remembered that there are no Republican insignia on me! I lost my cap in the rush, I don’t have a coat. We have no markings on the shirts. Therefore, he cannot conclude that I am the Republican. Maybe I can learn something from him! I pretended I was a Franquista and asked him: “Where are ours?” Noticing my foreign accent, he thought I was German and called me Mr. German. He said he could take me to his own,”ours”. They are there, in the third house. The headquarters of the battalion is there, he doesn’t know about the others. I thank him for his kindness and ask if maybe he knows where the “Reds” are actually. He said that they are up by the church. “I know that too,” I said, “shooting can be heard there. But here, in the center of the city. Are the “Reds” here already? Did you get to the city center somewhere?” He said he didn’t know. “I have to go to the headquarters for a drink.” “Okay, I said, “now I’ll come there too, just as long as I look around the other corner.” So I broke away from him and returned to our group. I found out at least approximately what the situation was on the opposite side of the “front”.

I took this second street at the head of the Spanish platoon. A tank is advancing in front of us. When we approached the corner of the central street, I entered the gate of the house on the very corner. The house is quite big. It will be an important position for us if we take it.

I enter the house with several Spanish comrades. It’s empty. I climb the stairs and look out the window. It’s a good position. But then I heard our tank retreating. I realized that I was left alone with those few comrades and with ordinary rifles, i.e. without a machine gun, without a launcher, in such a prominent position.

I looked out the window at the street. I see a tank pulling up. In front of the tank lies a dead comrade, stretched out, with his face turned away from me. But I recognize him by his suit. He was a wonderful friend, a Pole by nationality. His name was Gede. He was a painter, a good painter. He drew sketches for our propaganda posters, and edited the brigade newspaper. He went to this action with me, without someone’s order. “To be together,” he said. And there, for him, the fight was over. I feel sorry for him, very sorry.

I go down the stairs to inform my friends about the situation and to bring reinforcements. A machine gun burst through the door and I felt a pain in my knee. I’m hit. My leg can’t hold me anymore. I’m falling. The other fighters retreated. I am alone. Where am I? I look around me. I’m in a shop full of tobacco, cigars, cigarettes, and my leg hurts more and more. I picked up as many cigars from the shelves as needed to make a bigger stack. I put my leg on the cigar pillow.

I put the rifle down, take out the pistol and count the bullets. There are five of them. If necessary, four are for the Fascists, and the fifth is for me. At that moment, an acquaintance from the headquarters enters through the gate. I forgot his name, but I remember that he was a Slovenian from Ptuj. I later found out that he fell a few days later in the battle for Belchite (the town after which this offensive was called the Belchite offensive).

“There you are, I finally found you. I will come right away with a stretcher”. I told him not to do that, because from somewhere they were shooting at this very gate through which they would have to take me out, so we could all die. However, he doesn’t listen to me. He went out through the gate and in five to ten minutes he returned with two more Spanish comrades and a stretcher. Miraculously, while they were taking me out through the same gate where I was wounded, not a single shot was heard.

Ruins of Quinto

*

The doctor at the first aid station is Bulgarian. I can see the concern on his face as he looks and bandages my wound. Another wounded man, also a serious case, our man, started joking. “I hear, he said that you were going down the street in front of the tank, to protect the tank, right?” I’m not joking. My whole body is shaking. someone moans, and another consoles him: “Why are you moaning! I guess you knew that in war you don’t shoot with biscuits”

By train, full of wounded, we arrived at the hospital center Benicassim near Castellon de la Plana. These are villas, once the escape areas of wealthy people. Every villa is a small hospital. There are other wounded Yugoslavs in the villa where I am staying. There are Ivan Gošnjak, Peko Dapčević, Kosta Nad. There are the Canadian Croats, Edo Jardas and Anton Drašner. In the bed next to me is a young guy from Liubliana, Stane Bobnar. He will be my neighbor for months.

We are divided into two categories: those who are wounded in the legs, and therefore immobile, like me, and those who are wounded in the arms, shoulders, neck and chest and are mobile. They hold the link between us and the outside world. In the morning they go to buy newspapers and bring them to us other news, they sit on our beds and talk. They visit us several times a day. They provide us with everything we need in addition to what is more essential, food, which is brought to us by the Spanish nurses. A company of Yugoslavs often gathers around my bed. We talk about the homeland and the war, about the last battles and discuss international events.

Prime Minister Juan Negri is visiting us here for the first time. He walks through the rooms and shakes everyone’s hand. He thanks us for helping Spain. A strong man, with a healthy appearance. With a face and presence instills in our hearts some confidence in victory.

We are also encouraged by another visitor, the secretary of the Central Committee of the KP España, Jose Dias.

We are staying here for several weeks. They are evacuating us further south, to Murcia, a large university city. The university building was turned into an international hospital. We will survive the whole winter here.

I will never forget the head of the hospital, Professor Gomez, a neurologist. He cares the most for wounded people like me, that is, for wounded people whose nervous system has been injured. Our wounds interest him as a scientist. He often forgets about how we feel and treats us like medically interesting cases. He comes in sometimes in the morning, after several operations, with a bloody coat and a frantic look, he goes straight to one of the wounded, whose case is “ripe” for him to operate on. He appears before him covered in blood, points his finger at him and says : “Ese ombre ” (this man). The wounded man pales, but the professor is unaffected. The victim is placed on a stretcher and taken to surgery.

The same Gomes performed an operation on me that, even after twenty years, the doctors were amazed that it could have been performed then. Today, such an operation is common. It is performed on the spine (ganglion) in order to save the leg, which is infected with gangrene and which would otherwise have to be amputated.

After the operation, they separated me into a small room, far from main corridors. There is a department for the most serious cases. In are in the sitting room lies an even more seriously wounded German with a mangled body spine. Next to me is also a German with a serious injury on the upper part of the spine in the neck, and the other neighbor is a young man who I know him from the front, a Slovenian miner from northern France Pavle Krivic. He was seriously wounded in the head. His skull was injured and the speech center of his brain was shaken. With the greatest effort he’s looking for the word he wants to say, and sometimes he can’t even find it, gets sad.

Comrades, the mobile ones come to visit us. Mostly Karlo Mrazović. He regularly informs us about the news of which there is nothing in the newspapers — about our fronts, about events in our country. He entertains us with his stories from the Hungarian revolution and other memories. He tells us about illegal work. About Russia.

Nurses Maria and Antonia, from Spain, limit visits and conversations, according to the doctor’s order. They are quiet and peaceful. They take care of us as if we were their children. Maria, an elderly woman, has a husband and a son at the front. Antonia, a twenty-year-old girl, is engaged to an aviator, who is also at war. Together we comment on every event on the fronts and look for hope for victory in them. The senior nurse is Liza Gavrić, Austrian, married to the Yugoslav communist Milan Gavrić. She implements the Professor’s instructions.

Professor Gomez spends an hour every morning in our small rooms. He carefully monitors the consequences of each operation. Preparation for an operation on Krivic’s head. From a piece of bone from a leg or ribs intending to mend his skull.

He feels me, turns me over, looks at the wound below the knee. He squeezes the whole half of a lemon into it with his hand. Vitamins, he says, are necessary for tissue regeneration.

One morning he comes to pick up Pavle. Pavle already knows what it’s about, he also knows that operations on the head are performed while fully conscious, without anesthesia. For what little strength he has, his step is determined when he leaves the room.

After one hour, they bring him back on a stretcher. He looked at me with a smile. “It was strange,” he says, “but not too scary.”

The operation was successful. The very next day, Pavle felt himself quite well. He asks Gomez for permission to go to town, for a walk. Gomez politely turns him down. But – in the evening Pavle gets dressed. We urge him not to violate the Professor’s ban. But Pavle believes in his strength and resilience. “I’m a good boy,” he said and left. He comes back after a few hours, completely between her. Pale, sad, he lies down in bed, speechless. We’re all worried.

An elderly wounded man appears, an Italian, a peasant from the vicinity of Lago Maggiore, whom we jokingly called after that lake. He came to fight against Mussolini together with his son, a young man in his twenties. In Belchite, the father was seriously wounded in the shoulder, and the son was killed next to his father. “Lago Maggiore ” was showing us his son’s photo. We all noticed that the boy looked a bit like our Pavle. I guess that’s why “Lago Maggiore” became close to Pavle. He would visit him several times a day. He learned how to help him speak. “Lago Maggiore” would understand what Pavle wanted to say in half a word, even without saying a word, and he would pronounce Pavle’s thought himself, while Pavle nods his head and smiles contentedly.

That evening, after Pavle’s premature exit, “Lago Maggiore” also came to visit his friend. Pavle looked at him with sad eyes, speechless. “Lago Maggiore” turned away from him to hide his tears. He left the room, but soon returned, and went out again. Pavle started saying something incomprehensible. We called the doctor on duty, and he called Gomez on the phone. We told the Professor what happened. He watched Pavle with concern. He explained to us that the mechanical movement of the lips and tongue a symptom of inflammation of the cerebral cortex in the place where the speech center lies.

Pavle’s speech grew louder and louder. The eyes lost all expression. “Lago Maggiore” came and went more and more often. He was distraught. This lasted the whole night. Both nurses were there. Gomez appeared twice more. We could tell from his face that there was no hope. Before morning, Pavle fell silent. “Lago Maggiore” was standing next to him. The nurses shielded Pavle from us. Old Maria bent down – she covered his eyes. “Lago Maggiore” left the room. Tears ran down his unshaven face and beard. He lost his son for the second time.

*

In the spring, Gomez moved me to a large sunny room where about thirty wounded men were lying. I started to move around, on crutches, and to participate in social life. My neighbor was Stane Bobnar again.

Social life had developed a lot. Discussion circles were formed by language groups. Lectures were held for everyone in Spanish. There were also cinema shows in the big hall of the hospital. There we watched Eisenstein’s film, The Storm over Mexico. A singing choir was also organized.

City organizations, especially youth organizations, organize visits to the wounded and bring us gifts: books, oranges, and cigarettes. For the more mobile wounded, they organize trips around the city.

From that time, I vividly remember the conversations with the Spanish fighters. When we were at the front, we still didn’t know enough Spanish, and there weren’t many opportunities to talk, because we were divided into battalions by nationality. But just as there were Spaniards in our brigades, sometimes even entire Spanish battalions, there were also many in the hospital for Internationals. All those who participated in the battles and were wounded with us, were placed in the hospital with us.

Few of our people speak Spanish. Due to my earlier knowledge of Italian and French, I learned the language relatively quickly. Because the Spaniards often gathered around my bed and talked about their lives. They were mostly boys from the village. I remember their stories about the Catholic village church. In addition to the landowners who they had to pay rent, about how their life was made difficult by their privileged position, the church collected its tribute. The young man told us about how his brother and his fiancée worked and saved for several years to collect the church tax for the funeral, which was so high that the whole family had to contribute enough money to pay for the wedding. When someone in the family dies, they fall into debt that they cannot get out of for years.

In these stories, we found an explanation for the frenzy in the Catholic press throughout Europe about how the Church is being persecuted in Spain and how the Republic is anti-Catholic. Some of the wounded said that on the day when it became known that the reactionary government in Madrid had fallen, the revolution started in their village when they caught the Priest and expelled him from the village. These were simple people, mostly illiterate and with so little knowledge about the world and people that they often astonished us with their questions and claims. I remember a Spaniard who brought me another International and asked me to translate for him. The International was Hungarian. Since I don’t know Hungarian, I explained that I can’t interpret for him because I don’t understand that friend’s language. And the Spaniard was surprised and said: “How is that possible? You and he both speak a foreign language, so you don’t understand each other!” Someone else asked me one day: “Comrade, I would like you to explain one thing to me. I heard that since the Republic, the Sun no longer revolves around the Earth, but the Earth around the Sun.”

*

Major operations were taking place at the front. Among the biggest was the battle for Teruel. Then, in the middle of winter, many new wounded came to our hospital, and even more soldiers with frozen arms and legs that often had to be amputated.

In the meantime, Asturias fell. But, the main part of Republican Spain remained untouched. The Fascist offensive began in the Ebro valley. Exactly where we tried to penetrate to the north in the Belchite offensive, now the Fascist are advancing to the south.

A map of Spain is hung in the hospital yard. The flags mark the positions on the front. Every morning we gather around the map and watch how the front approaches the sea little by little in the Ebro valley. It may happen that the Republic is cut in two. And we are in the southern part, cut off from the French border. Evacuation by sea would be difficult. The Spanish navy is a crippled, it practically does not exist. Mussolini’s submarines rule the sea.

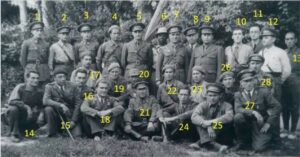

Our wounded in the hospital in Benicassim: Sitting from left to right: Kosta Nad (second), Ivan Gošnjak, Ahmet Fetahagić and Aleš Bebler (lying)

What will happen to us? There is excitement in the hospital. Some talk about it, among them Karlo Mrazović, that we will form guerrilla units. If the Fascists approach Murcia, we will go to the hills and forests and continue the war there!

The second thesis, which also had many supporters — I was among them — and I told them that we would defend the hospital. In the last days, anarchy will arise in the city, so we will to be able to stock up on weapons to your heart’s content and barricade ourselves. We will put sandbags or crates on the windows, and machine guns and a cannon if we find some somewhere we will put on the roof. And we will fight until the last drop of blood.

It only dawned on me later that we made decisions based on where someone was wounded. Mrazović was wounded in the hand and head, but his legs were intact. Of course, they like him and similar wounded were more likely to be guerrillas, and we, wounded in the legs, were ready to die on the spot, since in motion we would not only be useless but also a burden to the moving guerrillas. Mrazović promised me the best mule if I went with them, but he still didn’t sway me.

However, soon all our discussions turned out to be unnecessary. One evening, around eight o’clock, the order came to close all the doors and no one to go out! There was a commotion. That it is not about betrayal? Maybe some camouflaged Fascist in the city command wants to hand us over to the Fascists! Soon we will know from the Doctor that it is about evacuation. It starts at midnight. We should all be ready and gathered in the yard. Carriers will be provided for immobile wounded.

And indeed, around midnight they load us into trucks and take us to the train station. There they load us into cattle wagons. On pathos is straw. The group moves towards the north.

At dawn the next day, we had already moved quite far. We are approaching the critical point, where the railroad crosses the Ebro River, near the sea. We hear cannon fire in the distance. A formation of Fascist fighter aircraft suddenly appeared above us, machine-gunning us. The train stopped. Some comrades jumped from the train.

Another plane crashed. With the immobile and weakly mobile, I lie on the straw and listen to bullets and stones falling along the railway line. Nobody says a word. We are alone, unprotected, at the mercy of Fascist aviation. The shooting stops. Some comrades are coming back and some are not. The planes move away and the train moves on. But after an hour or two it stopped again.

What is going on? We are listening. Artillery fire is stronger, closer. The news reaches us that the Fascist artillery is already hitting the railway bridge over which our train is supposed to pass.

What now? How will we clams cross the big river? After some time, we learn that the bridge is badly damaged and that it is not certain that the train will be able to pass.

Later they brought new news: the bridge could support wagons, but not a locomotive. There is a possible solution: that one locomotive pushes us onto the bridge, and that the other, on the other side, pulls us off the bridge. But that still needs to be organized. We waited for an hour, maybe two. It seemed like an eternity had passed. Finally, we feel the maneuver of the locomotive: it pushes us in front of it onto the bridge. We stopped in the middle of a half-destroyed bridge over the river. Minutes pass that seem like hours to us, until the locomotive, which arrived from the other side of the bridge, hooks us up and drags us to the other side of the bridge. Tortosa train station is nearby. It has already been completely demolished.

We arrived in Catalonia, in that part of Republican Spain, which borders France.

Bad news comes from the front. The Fascist offensive cut the Republic in two. Few new weapons come from abroad.

We learn that we will be evacuated to France as unfit for the front. Evacuation is expected soon, in a few weeks.

First we met in the village of Mataró. We are located in a church, the only larger space in the village. My neighbor is Dušan Kveder. And there are many others Yugoslavs. There is a Frenchman – a former commander of the French battalion of our Brigade, Gabriel Fort. He lost vision. A bullet went through both of his eyes. A special nurse was assigned to him, who takes him around the city.

We are being transferred to S’Agaró soon. It is a seaside resort. In villas and gardens — August 1938, political and cultural life develops. Lectures are held on Spain, its history, this war, Fascism and the danger of a world war, and the USSR.

There are most Yugoslavs in the villa next to ours. In it, Veljko Vlahović is the oldest. In that villa there is the best order and the greatest cleanliness. Their wall newspapers are the best. And the most beautiful. The equipment and decor are the work of the Yugoslav architect Gašparc. Veljko has an exemplary system for rewarding and punishing — cigarettes. They receive followup collectively. One part is distributed to everyone equally, and one part remains as a prize fund. Orderliness, participation in joint works are rewarded. Disciplinary errors women are fined by bringing cigarettes into the common fund.

A cigarette is— gold. There are so few of them that often the three of us smoke one all day. A third of the cigarette, folded into a thin but long cigarette, is smoked together after breakfast, another third after lunch, and the third after dinner.

Juan Negrin is visiting us for the second time. This time there is time for a longer conversation with a larger group of wounded. He speaks to us about how many weapons Franco gets from abroad, from Hitler and Mussolini, and the Republic – very little. First of all, there is no aviation. All that came from outside were Russian fighters “Chatos”, and there are too few of them. If each of us would, after returning home to his own or any other democratic country, whichever he happens to be gave shelter, sent a plane from there, it would help a lot, the fortunes of war could still turn.

The evacuation time is approaching. They give us civilian clothes. Uniforms and everything that reminds of the Spanish war, whoever has a pistol — photographs, documents – must be handed over. Edo Jardas protests that it is his, I guess he has everything, we have to hand it over. Some are entitled to a miserable uniform. He returns to Canada; why can’t he appear there, at the gatherings to help the Spanish Republic, in the uniform of a Republican Officer? Ivan Kolar, the son of a miner, a Slovenian from northern France, who writes poems about the Republic, agrees with Jardas.

But nothing can be achieved. Everything has to be handed over and we get on the train like civilians. We will soon be at the border. And our comrades, who are luckier than us, continue to fight, the Republic probably cannot save itself, and it can defend itself for a long time, and who knows, maybe there will be an upheaval in the European and world frameworks. And we will not wait for that here, with the Spaniards.

Ales BEBLE

The following photo from June 25, 1937, at Ambite Mill during General Gal’s “soirée” has the entire XVth Brigade officers. Ales Bebler is standing left rear as #1. rmh

[i] George Nathan was actually killed in action on July 26, 1937, the last day of Brunete.

[ii] Sapir did not die at Quinto – rmh.