REBELLION IN GURS by Veljko Kovacevic

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

“The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War”

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks posted and provided links to volunteers.

REBELLION IN GURS

Veljko Kovacevic, Spanija, Volume 4, pp. 171-184

Two months have already passed since our second year in the camp. Who would have thought that France would reward us like that democracy only because we fought against fascism

in Spain! I am fascinated by the glorious past of the French race. A land of revolutions, uprisings, rebellions, a school of street fighting, how suddenly everything was betrayed. Now, on that revolutionary soil, concentration camps have sprung up in the morass, mud, and sandbars. They are packed with thousands of Spanish refugees. Several thousand fighters from International Brigades are with them. The glory of the Internationals gained in the trenches of Spain must be checked once again, it must be paid for, even though it has been paid for with thousands of lives.

When, one night, we were crammed into wagons waiting for our reception camp to leave Saint Cyprien, we had no idea where we were going. water, but we were somehow satisfied. Change. We’re going somewhere. It can’t be worse. We may no longer inhale wildly sand beaches of the Mediterranean, where sandstorms raged like in the Sahara. Just further from the sea. Ah, how we were resented. Ah, how its blue is clouded by sandstorms.

We’re driving. The wheels rattle monotonously under us. Only when our composition would stop in some places, we could judge by inertia what is in front and what is behind. But in which direction is our “forward” and what we are leaving behind, where we are going, we could not figure out. Oh, so they don’t take us to Paris – I hear someone else in the bottom of the dark carriage. We all laughed. We somehow drilled a small hole. We approached it one by one, taking turns and adjusting the eye. Once, leaving camp after a long drive, we managed to read the name of the Toulouse train station. So, we stick to the Pyrenees again. No way to part with them. What obstacles were there when we made our way in Spain! What a blockade the Republic had! And what a tragedy they were when the Republic expired! How freedom is buzzing now!

The excrement bin suffocates us with its breath. Day met directly with night. We can’t see anything, and as if to spite, none of us 50-60 comrades, how many of us are in that wagon, has a watch to tell what time of day it is. After a long ride, the train finally stopped. The command was heard: – “Get out, one by one, line up.” At the back of the head, the policemen in black uniforms surround us like hungry wolves, yelling, laughing, as if they want to say that we just got there where is our right place.

A large settlement of rectangular barracks surrounded by barbed wire stretched out before us. It seems to me that I have seen that settlement somewhere. Perhaps on some photo of German Concentration Camps, which were shown to us by German comrades in Spain. On the outside of the wires rose tall towers manned by policemen in black uniforms. Each one was decorated at least with one machine gun each. The Camp is also divided by longitudinal and transverse rows of wires. Everything is laid out in a straight line, forming several large rectangles, so that “the herd does not mix”, as one internee jokingly said. In each such rectangle there were dozens of shacks, with small windows under the roof itself. Sections like this were marked: A, B, C, D… On our gate, in large letters, it said “CAMP B” . Why exactly, “B”? Who did they give “A” to? We were always first on the list in terms of starvation, mistreatment, housing, and name. Who could be before us? Aren’t they some old prisoners? But it soon becomes clear to us that we are not neglected this time either, even though we are not under the letter “A”. Camp B relied only on one side, the shorter part of the rectangle, on the external wires, while our neighbors in “A” and C ” they leaned on two edges on the outer wires. That free outer side of ours was well fenced, studded with towers and police. Who could escape there? There is no reason for our landlords to be much afraid. It is a long way to the other side of the wire! How many will it take time to free ourselves from this wire mesh?

Our new Gurs camp is below the Pyrenees, near the corner where the Pyrenees meet the Atlantic. Good shelter from all the jets. And some rivers surround us. An expert must have been present when this land was selected for the Camp inmates. Did they did not bring any expert from Germany, or did they use the experience of the Germans? Entire rumors have already developed about the camps, which is understandable when millions of people are surrounded by wires. Concrete and thick-walled wires are cheaper.

In front of the guard in the Gurs camp

We will soon mark the anniversary of the detention in this camp. The war flared up widely. France is threatened. The third imperative is to take up arms again. We did not hesitate to express our unanimous willingness to fight together with the French people. This readiness of ours seems to be considered a serious sin. And why should it not be a sin now, when we have already been dragged away and condemned because we fought against Franco in Spain? We have to come to terms with the mud and dust of the camp, which changed periodically, conditioning the special “fashion” of the inmates.

Who was the first among the camp inmates to invent the new footwear for mud will never be established, but within a few days the new “fashion” flooded the camp. Until that discovery, during the muddy days, the feet were planted in mud up to the knees. People looked like dwarfs, true Lilliputians, some special human race that only walks on its knees. Even Neumann, a German, two meters and twenty centimeters tall, who on dusty days would have towered over all the inmates by a whole head, seemed to have shrunk in half. The new footwear lifted him and all of us above the mud. It is a kind of mud shoe, similar to a stool-three-legged stool. The new shoe is composed of four parts: upper, rounded board on which the foot was placed and three (and there were cases of four) wooden legs 40-50 cm long. That was the thickness of the mud. In the beginning, it was difficult for us to move. It took a lot of strength to pull such high heels out of the mud. But we got used to it. It’s true, we were never in a hurry. When I saw Neumann waddling with such a device on his feet, I was sincerely happy. He got his height again.

Even the days when dust reigned were not pleasant. The Pyrenean winds made real clouds out of it. One would often get the impression that the Camp was burning in some yellow smoke, through which the inmates could be seen like firefighters in a raging fire.

In the first months of 1940, the regime of the Camp Authorities became much stricter. Hunger pressed harder and harder. The faces of the inmates became elongated, and our “hospital” became too small. The large urinal qiblas [strange word, meaning direction to Mecca??], which we carry to the river every day, to be emptied and washed with our hands, although they are much easier, are getting harder for us day by day. How skillful is the camp sewage system is solved! And we really look like a canal when they line us up in long lines, two by two, qibla after qibla, accompanied by policemen. Those in the “hospital” don’t have to wear qiblas. So, shouldn’t a man envy them? Dysentery is not even considered a disease. Who would carry the qibla? Should the entire camp be declared a hospital? Our doctors-in-camps thought of some coal to cure us, but they can’t even heal themselves. Doctors say that starvation is the best medicine. If there was any truth in that, then no one would get sick. And when one day this misfortune befell me, my two “roommates” spoke with their own pathos: “Starvation, comrade, starvation. From today until the next day, we will eat your portions. We hope to repay you.” For three days they ate my vegetable portions and that wretched piece of gooey bread, “wishing” that the disease would not be treated gradually. Soon, both of them paid back. I ate this unforeseen contribution with special pleasure, returning their wishes that the disease should be treated as gradually as possible, in a more natural way. The game of dysentery continued continuously, without detouring. It will remain our inseparable companion in the wires.

The German offensive seemed to be floating in the air. The police more and more often break into the camp with dogs, which, it is true, they keep on a chain. Rumors spread through the Camp about the alleged formation of some work companies for the needs of the front. On Mazinov’s line, it looks like unarmed people would be welcome. There are works there for mining and demining and places to “honorably” die and to “honorably” solve the problem of Internationals. “Mines are weapons, too. Interbrigadists, you have experience, here is your chance to prove yourself once again in the minefields for the good fortune of France,” is inserted more often. “Only if armed are we are ready to fight at every place on the front”, we answer. “Only without weapons. If you don’t want to be kind, you want to go by force”, threatened by the police.

The plan was all too obvious: to destroy the Internationals. Governments would be grateful for that, especially ours, which has long since revoked our citizenship, prohibited us from returning to our country, and referred us to the French police. True, before that she also sent us her emissaries with printed penances, calculated for the needs of the police and the press. We were asked to sign them personally, to declare that we regret having fought in Spain, to spit on our struggle, to become traitors. “Only this signature and you are free, the door of Yugoslavia is open for you,” the emissaries said. Instead of signing, we spat in their faces.

The police tirelessly agitated and asked for volunteers for the work squads or, as we called them, for the “death squads”, which, in fact, will be the case for many who fall for them.

Since there were no more volunteers, the Camp authorities began to designate Internationals and Spaniards according to lists, according to orders, and to classify them into work companies and send them to the front. Several companies made up of members of several nations have already been dispatched. It was not our turn, the Yugoslavs, even though all the other national groups had already started. It looked like the International Brigades had come to an end. What does the Party Committee of the camp do? Why did he cross his arms and accept such a reality? Do you bend your neck and put up with the order of the police? The slaves also find a method of fighting, and often very successfully. If there was at least one Yugoslav sitting in it, I am convinced that nothing would be done. Should we be satisfied only with the fact that no one volunteers for labor companies anymore? Why do the Yugoslav police bypass us? That he is not preparing something more difficult for us than other Comrades? We resented them a lot, we know that. A few days ago, when they suddenly broke into our barracks, they found a truck full of Marxist literature in various languages. They were baptized by a miracle. They couldn’t possibly explain how it got into the Camp, how we brought it in, how it slipped through the wires. They remember it, they do. It will certainly never occur to them that all our flasks, in which only the neck was covered with water, were hiding one or two books each. There were other ways, no less successful. We are aware that we will not be able to avoid that moment when they will try to examine our group as well. Danger was looming ever closer. We saw it, although it was not revealing itself. It has its own invisible signs, which some invisible senses of the camp inmates feel. And the last barrack around us was built. And all this is happening in front of our three barracks, but, not even to feel sorry for us. The Yugoslav group is not waiting idly by. Everything is ready for roll call. As for the actual decision of what to do, it was made as soon as it was established that the work comps did not mean the physical and political liquidation of the International Brigades. We are waiting for the roll call. The Party Secretary of our Committee, Ivan Gošniak, presented the Committee’s conclusion that the Yugoslav group must oppose the police by force. To fight until the last breath. Do not allow a single Yugoslav to be dragged away.

A group of Internationals next to the camp wire (Ante Mioč in the middle)

A group of Internationals next to the camp wire (Ante Mioč in the middle)

We have been waiting for the roll call for days. The decision is simple: resist by force. And where is that force among the unarmed, starving prisoners who could deal with armed men? What does resistance by force look like in such conditions physical? Physical resistance of 300 bare-handed Yugoslavs! If you would have been joined by a mass of about twenty thousand inmates, so we could do that and be, although bare-handed, still a great force. We could not be blamed for this kind of decision. We have no directive from above for such arbitrariness. It was really brought about arbitrarily, in a group of several hundred people, who carry the thought that they can perform a miracle, but that they can also lose their heads. We even have to keep quiet so that word of our intention does not spread.

All, despite the ban, the word about the group’s resistance is already breaking through that crowd, and new work companies are leaving one after another every day. The queues were seriously forming. Camp gates open and close more and more often. No letters or messages arrive from those who are leaving. However, the police seem to really forget us and spare us.

And here it is at last on April 1, 1940. April Fool’s Day. I have to deceive someone. Ever since I was a child, I haven’t missed a single one without deceiving someone. And on April 1, I told a group of comrades as special news that I had learned from reliable sources that we would be released within three days. I threatened them not to tell anyone, because the spread of such voices could only get in the way. At first they believed me, but someone remembers the date. We laughed — bitterly.

Around eight o’clock a policeman came and read from his list the names of the ten Yugoslavs who should be there the next day in front of the administration building, where it will be assigned to a working class company and leave the camp. So they could get drunk too. Isn’t that some trick by the police? And he too he can joke. Where else did the police make fun of the arrested, even on April 1.

April 2 is upon us. We are only one night away from it. And what could that April 2 be like? At the front, we often expected raids, and that expectation was always more difficult for me than the raid itself. Man thinks, fears what tomorrow can bring him. Do others think like that? This tomorrow threatens, it seems to me, beyond all previous ones.

There is mud in the camp like never before. Our heels fall all the way to the feet. It’s constantly in my head the committee’s final decision:

“Thwart the plan of the police. Do not allow any Yugoslav to be dragged into labor companies. To resist physically until the last breath of strength”.

“There will be mud plowing tomorrow,” I heard someone say. What kind of plowing does he mean? I can’t understand.

April 2 dawned. In front of the administration building of the camp, about fifty people gathered from other national groups were staring. Candidates for work companies are being called. What names are there! Responses are heard. No one responded to the roll call of the ten Yugoslavs. The policeman repeated the names several times, but in vain. Immediately after that, a police officer came running with a message from the Camp Commander that certain Yugoslavs should report quickly to the meeting place. The whole group is waiting for you, and the train has a specific departure time. You are always the most undisciplined novice. Just wait a bit – I hear some ironic voice behind me. Some Comrades cough forcefully and unnaturally. Maybe the policeman will understand that cough better than the remark of the one who said to wait a little. The policeman leaves, repeating over and over again: “Just quickly, quickly, everyone is waiting for you.”

After half an hour, another policeman, who also had a rank on his shoulders, ran in enraged. He read out a threatening order by which the camp administration told us that they would use force if the Yugoslavs who were called did not respond within half an hour. Again someone throws in: “Who will pay for the train being late if we don’t make it on time?” This time no one coughs.

The whole group was together. Three hundred scowling faces like I’ve never seen before, as if something threatened. By all accounts, a storm is on the way, but no one can yet foresee its strength and duration. We wait for 8:30 AM. The first ultimatum has expired. Here is that policeman again with an even harsher ultimatum than to me, but with a deadline of one hour. We cannot understand why they extended our deadline so much. Maybe we should think a little more seriously about our procedure. If they wanted to achieve a psychological effect, they really achieved it, but the opposite of the one they expected. A friend showed me pockets full of small stones, as big as chickens. Ah, my mighty weapon. That second class also goes by and there are no tickets.

It wasn’t until around 11 o’clock that we saw a well-armed group of police officers approaching our three barracks. They wore helmets on their heads like never before. And that means something. All of them are large, strong, well-nourished, and their faces are somehow more red. The mass of camp inmates from other national groups, not yet really knowing what this meant, moved away, making way for them. And it’s not convenient for them to get in the way. They stopped in front of our second barracks. One of them commanded “calm” and started calling out. The first on the list was Vicko Antić. Ah, that cursed alphabetical order can be inconvenient for some people. And at the front, for special tasks, it’s “A” and “B”. first to strike. The police officer says that name and stops to hear the response. Instead of Antic’s response, three hundred throats burst out: “Hooaah, Hooaah “. As if on command, that ” Hooaah ” began to conquer shack by shack, capturing every camp, all national groups, thousands of inmates. It soon turned into one continuous ” Hooaah “, which, it seems to me, made even the mud tremble. Camp inmates are on their feet in wheat mud. Their frenzied voice echoed continuously with undiminished ferocity. The Pyrenees seemed to accept them and return them stronger. With that unique cry came strength and a willingness to face bayonets and barbed wire. Our group was no longer alone. The latent power of the mass, everything that had been accumulating in it, suddenly, literally, burst through, washed away.

The surrounded policemen quickly retreated towards the gate, “B”, with the screams of the detainees: “Long live the International Brigade! Long live the Spanish Republic”. The song of Madrid was also heard: “Iron Companies are going to fight”. Battle cries rang out from the Spanish front. The mass rolled through the mud towards the road fenced with wire, which divided the Camp into two parts. In front of the strong fence, thousands of dwarf-looking detainees were crowding. The feet were sinking deep into the mud. The Spanish slogans were replaced by new ones: “Long live the French people!” Down with Fascism! Down with the tyrants! Give us weapons to fight!”

The police retreat and occupy the towers around the wires. Barrels of machine guns and rifles are coming from all sides. Just one command “fire” and thousands of people would find their death in the mud. Will it come to that? For such an order, only one step of a camp inmate would be enough. It was not the time for that. “Bravo Yugoslavians imprisoned in wires. What it didn’t hit you earlier. Today there would be more of us together,” Camp inmates shout at us from all sides.

After a few hours, the rumbling of trucks was heard in the distance, which grew louder from moment to moment. A motorcade was approaching the camp. Soon we saw the front of the column, which stopped in front of the main gate. The whole column could not be seen. It was too far. We also see the formation of some army in blue uniforms, quite different from the police uniforms. Maybe it was a new police force that arose during the war. Maybe it’s worse than the one we’ve been dealing with for more than a year. Excitement among the inmates grew more and more. The heated mass got even hotter. Just so that he doesn’t attack the wires, just so that he doesn’t forget, so that he doesn’t miss the moment after which the fire starts.

We, the Yugoslavs, who won the battle, should wait as long as possible. Big unknowns and big risk, big responsibility. In military terms, the main strike should be carried out by us. He is yet to come. What will be the confrontation between armed columns and unarmed people?

The camp doors opened wide. A column of uniformed men, in double rows, with bayonets on their rifles and helmets on their heads, appeared with a solid, intimidating image. The front marches all the way to the end of the road and stops there. We could see the beginning behind the main gate. The French army, part of which we would like to join if we were to fight together against Hitler! Will they use weapons against us? We are also a disarmed army. Republican uniforms still prevail.

At the Officer’s command, the halted column is split lengthwise into two symmetrical parts. On both sides of the camp, they turned in two rows. In front of our group, their ranks are the densest. We look eye to eye with the soldiers. The command was heard: “We’re done”. Hundreds of barrels were pointed at us. Just one bomb and hundreds of inmates would fall. Another command was also heard, but from the inmates: “Into the barracks or we’re going to show up and shoot.” From the mass came the thundering cry: “Les soldats sont nos freres”, broke out from all throats in unison as if under the baton of a possible conductor. And we consider them brothers in arms. On their front stood the same enemy from Spain, with whom we fought for two and a half years “Long live the French people”, “Down with tyranny”, “Soldiers are our brothers “. The “Marseillaise” also spread out. The enraged looks of the soldiers began to soften. They looked at us with a different look, somehow closer, more friendly. Their guns from the “ready” position began to fall “to the leg” one after the other, until the last one.

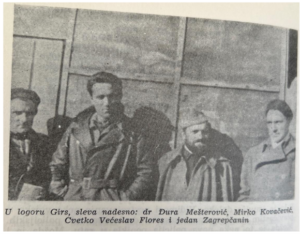

In the Gurs camp, from left to right: Dr. Dura Mešterović, Mirko Kovačević, Cvetko Večeslav Flores and a man from Zagreb

“Army forward”, repeated command after command. Not a single soldier moves. Now they looked at us, it seems to me, as accomplices in our resistance. The fearless attitude of the people on this side of the wire developed human feelings among the soldiers, who remained very deaf to the commands of their officers. “Marseillaise” echoed again among the inmates. And for the tenth time they heard the command, “Forward”. Soldiers seem to be deaf. Finally, he gave the command: “To the left circle”. He led them back to where they came from. The inmates’ applause lasted until the last soldier walked through the gate.

A few hours after the army left, the rumbling of trucks was heard again. Surely it will no longer be an army. The column was black, as if it was covered with a long black cloak. And the helmets on the policemen’s heads are black. Only the weapon glitters.

The policemen skillfully jumped out of their vehicles, even more skillfully than the army, and quickly lined up in attack order. We are aware that this time it will not be like with the army. For them, the song “Marseillaise” or our calls do not stick. A great danger loomed over the mass of the Camp. And what next? How long can we go on like this? This time, the barrels pointed at us did not fall on our feet. “Ready”, they cocked the trigger. “To the barracks, we order for the last time,” the Command was heard. In fact, that was the last moment. We are retreating to the barracks. The mud cleared from the inmates. But shouts echoed from the barracks as before. Police officers in cordons in the mud. One group of several hundred surrounded three Jugoslavian barracks. When they had tightened the hoop well, we began to fall in between the rows of wooden beds, made of some old sheets. Two long rows of beds, 50 on each side, stretched along the shack. Between them stretched a corridor a little more than half a meter wide. We huddled by our beds, expecting an attack. A group of ten policemen broke into our barracks. Jelisija Popovski‘s bed is next to the door. It should have started from him. And in fact, everyone falls for him.

“Will you work in work companies?”, one of them asked.

“No”, Jelisije answered, so that the whole barracks could hear him.

The five fell on him as if they were going to tear him apart. Four guards had their rifles pointed at us, and one, the strongest, stood at the door. Strict distribution of work. The leader of the group, at Jelisi’s answer of “no”, firmly grabs his beret to pull him outside by his hair. But to the general laughter of about a hundred of us, the beret remained in the policeman’s hand, and Jelisi’s bald head seemed to flash. This irritates the policemen even more, as if they have been tricked, so they come to hit him. Jelisije threw himself on the floor, grabbed the legs of the bed with his hands, but they quickly pulled him away. Two of them dragged him by the legs, and the others hit him until they pulled him out the door. We could clearly see how Jelisje left behind a deep furrow in the mud, along which he was dragged on his back. This is the plowing that I mentioned a little while ago. In such a way, they grabbed and dragged them away one by one, with more and more forceful physical confrontation. Each victim would be made to stand up at the door, in order to give the large policeman, who was waiting there, a chance to knock him unconscious with a punch to the head. His task was just that. The resistance stopped at the door. People were falling into unconsciousness and then dragged through the mud somewhere into uncertainty.

Constantly the same question: “Will you work?” And the answer is the same: No”. After that, an unequal struggle began, the struggle of one starving and unarmed inmate with a group of police officers, and it would last until the detainee was unconscious.

About thirty have already been picked up from our barracks. I envy the first one. The hardest part is waiting for your turn. Just once to talk to you and those worries. Each comrade defends himself in his own way, each wants to surpass the previous one. Here’s the turn of my nearest neighbor, bed to bed, Ivan Pihler. He did not wait for the police to ask him about his work, but before they fell on him, he threw himself on the floor and firmly grabbed the legs of two opposite beds with both hands. Two policemen grabbed his legs and started dragging him, two of them hit his hands to somehow pull him out, but surprisingly, Pihler didn’t give in. Holding tightly to the legs of the bed, he also pushed those thirty empty beds in front of him. A real gift. We just envy him. No one can beat him. But the tamer at the door calms him down too.

Finally, it was my turn. I did what others did. I don’t remember how I got through the door. I only regained consciousness behind the second shack broken into. Romanians were imprisoned in it. When I opened my eyes, I saw my legs under the armpits of two men with half-faces showing. My hands dragged somehow behind me, as if they had been ripped from my shoulders. The eyes and nose, like fins, were out of the mud and I feel myself breathing and looking. I have to admit that this kind of skating is not particularly unpleasant for me. I feel the fine mud moving under my feet, on my back, under my armpits, around my neck, like some cool water stream. Only if you didn’t watch it. His head is down instead of his legs, and his legs are majestically feathered in front of the policeman’s shoulders. And the policemen are muddy. This is really plowing with human bodies. A little later I noticed a few of these carts. They all went from our three barracks. It seems that it is up to the Yugoslavs to pay the bill for the entire Camp. Some distance away I see a strange group of policemen, they are fighting with someone. A large man towered over them by a head. They rushed at him, and he would turn around, wave his arms and body, and knock down several of them at once. I soon recognized that it was Laza Latinović. I still remember him from the Spanish front when he alone, without anyone’s help, pulled an anti-tank gun up a hill. Today, it seems, he will not be plowed like us. They rushed at him to knock him down, bounced off like a rock and charged again, but they had no way to knock him down.

When they dragged me to the road, they let go of my legs and I stayed down. A policeman kicked me in the ribs when leaving. It hurts me somehow dull and deep. Some others spit on me.

On the right were three trucks full of Yugoslavs. The trucks were facing away from the gate. What is that? I can’t possibly understand where they intend to go with us, when there is no way out on that side. I’m still lying down. I pretended to be dead for a while. My head was spinning. They called me from the truck, but I don’t respond to them. Again, a policeman kicked me in the groin and spat in my face. Okay, I mean, I’ll play a little more. They are calling louder and louder from the truck. I turned and winked at you. They laughed: “Get up, you fool,” someone tossed in.

“Carriage” after “carriage” continued to arrive. A Camp inmade was dragged down, lifted up and loaded into the truck. I saw how they also deal with the celebrated hero from the Spanish front, Mirko Kovačević. His hands are wrapped around his back, they are pushing him forward

themselves and hit his back and head. As soon as he saw me lying down like a dead man, he jerks hard and pulls out one arm, but they quickly tamed him. I winked at him and smiled a little. He understood me. He smiles back at me. Realizing that my posture is senseless like this and that I can get even more beatings and be more and more nastily spat out, I jumped to my feet and jumped into the truck. “Hang on, let us help you too,” one friend joked and hit me knee. “I would like us to cry over you.” Someone sang from the corner of the truck: “Las compañías de acero cantando a la muerte van”1.

The trucks finally started in the opposite direction from the exit. But after a few hundred meters they stopped in front of two of the military barracks, which were surrounded by several rows of barbed wire. A Camp within a Camp. A kind of solitary confinement in the Camp. Out of a total of about 90 arrested There were 76 Yugoslavs who were put in the bottom of the barracks. The barracks were only used for selected inmates, like prison cells. And we deserve such an honor. And we were enough, no matter what else awaits us.

There were no beds in the barracks except for a floor of muddy planks, which we muddied even more. For the first two days, we received neither food nor water. Instead of us going on hunger strike, the police used our weapon. But the food came through invisible channels, slipped through so many wires and through so many guards in a magical way. It was sent by our group, emptying our “golden reserves”, as we called those small stocks, which we created for rainy days from the packets we received from the Party from Yugoslavia with the help of the Red Cross. Well, by God, this paid off. “Only to last like this”, – says a friend jokingly and chews a good piece of bacon with plenty of fresh white bread. – “And when we go back there, it will be a piece again bacon as a sugar cube, for three days.”

In the eyes of the Camp inmates, we became heroes. The whole Camp was watching over our fate. We would often sing a song because it was sung to us, and so that the surrounding barracks would hear us, and in that way give a voice about ourselves and our attitude. The police were raging, banging their butts in the barracks, storming inside. We were getting louder, more defiant. And when, somewhere on the tenth day, the news arrived that since April 2 the police had not even tried to draft anyone into the labor companies, we were really happy. All that we suffered before on April 2 was too cheap a price for what we achieved.

Somewhere on the twentieth day, a Company of Regimental troops came to our barracks. They quickly lined us up, surrounded us well and led us towards the gate. What are they up to? What should we do now? We were in no doubt. However, we believed that we were not being herded into labor camps. True, the police immediately told us that they were taking us for a haircut. As soon as we hit the road, the inmates started running out of the barracks. Within an hour, thousands of prisoners were lined up on the wires. The Camp looked like it did on April 2. All the calls were addressed to us.

We greeted them by waving our hands like true celebrants. The police stopped us in front of the barbershop, in plain view of the inmates, in order to appease them. There they cut our hair, then photographed us one at a time, from the face and profile, and took fingerprints for the tenth time. After that they returned us to our separate barracks.

For people like us, there were worse camps than Gurs. We had heard about the infamous Vernet, it’s true, before and never thought that we ourselves would soon be visiting there. In the middle in May we found ourselves in its wires. In the next weeks other Yugoslavs and other nationalities also came to us because the authorities have convinced themselves that there is no difference between groups.

The uprising in Gurs on April 2, 1940 had an inestimable significance and was above all earlier and later ones, and there were quite a few. We completely thwarted the intention of the French authorities to destroy the Internationals. It’s true, we, the Yugoslavs, have experienced the most, but that’s nothing compared to the kind of victory we won. The experience gained from that great action was a great lesson in our further struggle. Not even in the infamous Vernet for the fluid, cruel police regime could it be maintained for long.

___

1 Steel companies go to their death singing.