ALBACETE by Dr. Gojko Nikolis

“The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War”

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks posted and provided links to volunteers.

ALBACETE

PASSAGES FROM SPAIN

Dr. Gojko Nikolis, Spanija, Volume 3, pp86-122

The seat of the headquarters of the International Brigades of Albacete, with the help of the imagination of the romantics, could be imagined as the one from which its natives were evicted and where the new Spanish alcazar was established on the cliff, or, at the very least, as building order, the order of staff strictness, where everything it moves and happens according to a certain established plan, where movements and words are kept to a minimum, the town is rational and efficient at the same time.

In fact, at the first step, Albacete presented itself to me as it is: a gray, desperately gray palanquin. And only the combination of war circumstances, as often happens in wars, could have prevented this previously unknown and unattractive town to rise to the top of the list of geographical names that were mentioned in Spain and the world at that time. Of course, dusty streets and houses of disreputable architecture remained from its original appearance. The specific wartime novelty was represented by banners and loud microphones on the streets, shelters in parks and the crowd that was pressed all day long until late at night in the darkened streets and towards the fans: the domestic world, the Spanish world, and the international world, of various nationalities, the most diverse professions and function, people who, with their selflessness, created and spread the glory of International Brigades and those other accidental companions and combiners who, like lichen on an oak tree, they lived off that fame for their own account. I stepped in front of Comrade Telge, head of the medical service of the International Brigades. When he asked what I had done so far as a doctor, I mentioned to him, honestly and naively, my work at the skin-venereal department of Niš hospital.

Telge happily exclaimed: “I really need it! You will go to Pontones.”

I had a hunch that “Pontones” meant something similar according to my wishes. My wishes? Like all the volunteers who went to Spain, I could not imagine my service to the Republic and our common cause in any other way than to be at the front, clearly, as a doctor, where, as we thought, the only way to pass the test of morality and justify one’s existence in a war of such character as the Spanish one. At first glance, this kind of desire may seem naive and romantic, because the front is really any place where there is something to do, where there are difficulties, and in the background of the war there are plenty of such fronts. However, there were also very real psychological reasons behind this desire: every normal person in war, with the exception of extreme individualists, tends to fit in somewhere, to disappear to a certain extent in the ranks, in the column, in the crowd. Along with this desire in the warrior, there is also another, the opposite: to stand out, to lead, to guide a column, a unit behind him, when this falls into a crisis. It is a kind of due return for the patronage that the column provides (if it provides) to the individual. So harmonious the mutual relationship between the personality and the unit, if it is established, then the emotional and rational awareness of their interdependence is one of the essential bases of combat morale.

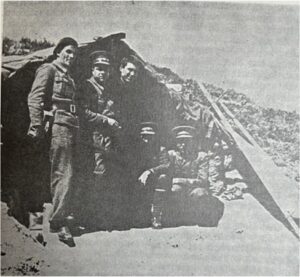

Infirmary of the “Dimitrov” battalion in position. From left to right: Tabakov, political commissar of the battalion; Dr. Franek, deputy chief of health care of the international brigades; Angelov, paramedic in the battalion; Telge, head of the medical service of the international brigades and Filipović, officer of the headquarters of the base of the international brigades

For us, volunteers from Yugoslavia, there was another factor that acted to make the concept of “units” reflect in our minds as the promised land: our people in Spain were scattered everywhere for a long time in various units at the front and in the various units in the background. From the point of view of internationalism, this practice was justified, it had good results, but a significant number of people, especially those who did not speak a single foreign language, felt lost. That is why our people had a constant longing to meet “their own”. It must be admitted that until the establishment of the “Dura Dakovic” battalion, it was not easy to satisfy this desire, but after the establishment of our battalion, it was even more difficult to explain to the Yugoslav that some “greater needs” demanded that he be assigned to another, and not to the Yugoslav unit.

I asked Telge, what is Pontones and where is that place?

“You’ll see when you get there. We’re leaving today in an “Ambulansija”[1] Be ready.

All my assurances that I came to Spain to fight in the afternoon I’m leaving on the front, in the unit, that I don’t want to work somewhere in the background, that I want to be together with my compatriots, etc. are just what any reasons are worth after the decision which was already brought by the Officer. Comrade Telge, like everyone else Sanidad officer of the past, present and future, remained uncompliant:

”Pontones is also a front, and a very difficult front. You are going to Pontones!”

Although I felt that the word “front” had only a metaphorical, and perhaps ironic meaning, and that Comrade Telge used that word with the cunning intention of hitting me in a weak spot, I must admit that he achieved that: if Pontones is really in this difficulty, then, I concluded, I should go there; it is not worthy for me to shrink from difficulties.

“Ambulance”, all painted in protective colors, took me with a lot of noise along the winding Madrid road. But not for long. I guess after about twenty kilometers we turned off the road onto something called a road, actually a track dug by motor vehicles in the bare steppe. I asked the Responsible, what kind of hospital we are going to?

“Pontones! Hospital de Sangre!”

“What is that? Sanatorium for tuberculosis?” I asked not understanding him.

“Yes, for tuberculosis, but only of certain organs”, added the chauffeur with a mocking smile, surely considering me a patient too.

“Was it at least nice?” he asked me, but I didn’t immediately understand the true meaning of his sarcasm.

I look around from the driver’s cab towards the patients. All sailors. Only then did I begin to understand Telge’s delight when he heard that I worked in the skin-venereal department. Are there any such patients in Spain? To hell with it! Why didn’t I keep silent for those three months of my medical biography? Why didn’t I just mention surgery? So that’s the “front” I’m headed to from distant Yugoslavia!

Soon, the “ambulance” plunged into a thicket of young pine trees that bent, but also scratched the metal sides of the car. The driver did not pay any attention to it, performing real slalomskiing between the trees. The car and us in it bounced high, crossing at full speed over gravelly dry riverbeds. The whole atmosphere and driving style reminded me irresistibly of a stagecoach race in western movies. Fortunately, we were in the deep back of Spain, so there were no bangs in this race, but I still feared that the “ambulance” wouldn’t be flying any wheel. In fact, it was my first encounter with one of the phenomena of war that I will be able to follow countless times.

In war, a new relationship between man and material is established: the only weapon becomes the object of his attention, but also of love. A man serves a weapon. Everything else, man thinks, should serve him, and in that service he can and must be mercilessly wasted and destroyed. Only used for the first time, but still valid material (shirt, shoe, vehicle) is discarded at the same moment when the first opportunity arises to be replaced with a new one. For his dedicated service to weapons, combat, war, homeland, ideals, man seems to want to reward himself and to somehow confirm, compensate and indemnify the integrity of his personality, which feels threatened by being “too much”, as it seems to him, gave himself to weapons, to war, to ideas. Only a warrior of average consciousness is somewhat freed from this tendency. That’s why, among other things, glory be to the Quartermaster team, pharmacists and other guardians of “state property”!

The “ambulance” nevertheless reaches a settlement in the middle of a pine forest and suddenly stops there. Pontones? No. Pozorubio[2] military camp. Barracks in a circle, masked in greenish paint; that this machine gun model is called “Maxim”. Weapon! This is my first encounter with the weapon of our revolution and that’s why I shout to him in my heart: healthy weapons! These are no longer pebbles, rolled out of the Belgrade cobblestones, but the steel-bullets of Russian rifles, the steel-bullets are high-powered, lethal, the shots reach the enemy or stop at one hundred meters, eight hundred meters, one thousand two hundred meters. So keep a decent distance: I love you so much, weapons!

Then, while I was standing in front of the machine gun, a soldier of athletic, almost martial stature, arms crossed on his chest, and gentle, somewhat absent eyes, approached me as if in a daze.

“Where are you from?”

“From Yugoslavia.”

“Me too. I’m here in officer school.” It was Dušan Kveder.

Finally, we arrived in front of a rather lonely farmhouse, surrounded by a wall. A typical Spanish cortijo.[3] What am I doing here? I’m not an agronomist. But it is Telge’s “front”, Hospital de Sangre.

PONTONES

The head of the hospital and the only doctor in it welcomed me joyfully. It was Dr. Šajnberg {Dr. Matifia Scheinberg, 545/3/669/1 – rmh}, a Lithuanian, young and very lively, who had come from the Soviet Union. Even my first impressions of the environment in which I was going to spend exactly eight months, did not at all coincide with the term “front”, and that term was supposed to mean that I was going to encounter extraordinary troubles there. The hospital was mostly functioning normally in everything. The spirit of staff and patients was quite high.

The cortijo rises on the very bank of the timid and quite clear Jucar River. In all directions, the bare plateau, the steppe, stretched endlessly. Only here and there on the horizon a lonely tree. We were in the heart of La Mancha, the birthplace of Don Quixote. Windmills have disappeared, but not Don Quixote.

Over time, life in Pontones even became interesting to me. There was enough medical work. Admittedly, medicine at that time could not boast of quick results in the treatment of Pontones patients. It required a lot of patience, and we were often overwhelmed by the feeling of complete helplessness. During those eight months, several hundred patients from all over the world, from Canada to China, trusted my conscience and the skill of my hands. I got close to extraordinary people there and, as a doctor, I gained grateful friends to them.

Apart from a few of my unfortunate compatriots, I don’t know of anyone else who still exists in this world. Where is

Franz List now, an older sentimental German, contemporary comrade of Rosa and Leibknecht?

For days he told me how things went with them and why they lost the battle. Where is Ernest Kunčik, a youth from Vienna, a member of the illegal youth organization “Roter Falke”[4], a participant in the February uprising of the Viennese proletariat in 1934 and, until recently, a warrior from the Sierra Nevada? Where is that benevolent, fat black man from Cuba who, with so many patiently put up with my searches for his cubital vein: you can’t see it, because his skin is blue-black, you can’t feel it because he was fat! They say it’s not easy to find a Negro with that body. It’s even harder to find a vein in a fat Negro.

After Spain, all those sick Internationals scattered all over the world, or were swallowed up by Nazi camps, or perished on the battlefields of the Second World War, or… maybe there is someone else alive who continues his life in veteran isolation?

The working collective of the hospital was a truly homogeneous collective. I don’t remember any significant dispute between these people. During my entire stay in Pontones, not a single punishment was imposed. It was worked according to the principle, “all for one, one for all.” Everyone knew his task, but if he couldn’t complete it on time for any reason, someone was immediately found to come to his aid. I will explain what we have to thank for such a degree of mutual understanding in the Polish collective.

We had neither party organizations nor party life in the conventional, statutory sense of the word. It seems to me that the internal conditions in Spain did not allow it. However, the presence of conscious forces, the Communists, was felt everywhere. They, without any previous meetings and “concluded waiting” by their example, brought the spirit of camaraderie, respect and interpersonal solidarity into the team. I think that was very important.

The Political Commissar of the hospital, an Austrian called Sep, an invalid from Jarama, made sure that patients and staff were both constantly informed about the situation on the fronts and political events in the country. Stamps were plentiful. We held cultural events every week. With my help, a Spaniard, a student, translated Matić’s poem about Anita into Spanish. The recitation was an extraordinary success. In fact, every meeting of the hospital, called for any occasion, ended with a “fiesta”: singing revolutionary songs. Their value was enhanced by the contrast: we met and sang – in the church! There was one hospital dining room in the church. At the end of each “fiesta”, the “Internationale” was sung, in a calm attitude with clenched fists. I could never get enough of the people singing the “Internacionale.” Each national group brought some of its peculiarities to this singing. The Germans sang to the rhythm of the march and grimaced.

Italians: with longing eyes and molto, molto cantabile.

The English: my attention was only attracted by their words, nothing like: uaj-uej, haw-quau.

The Spaniards performed their own variation in the chorus of “Internationale”. That’s why after the first two verses, we usually give up the attempt to say anything. We would settle for a melodious humming.

That’s how the days of summer and early autumn of 1937 passed and I still couldn’t understand why Pontones got an honorable place in the ranking of Telge’s problems. Admittedly, our isolation from major events was complete. We never even heard a plane fly over us, and we only knew about the battles on Brunete and Belchite from the newspapers. My boss, Dr. Sajnberg, showed more and more signs of impatience and he managed to scrape {escape} from the Pontones at the beginning of autumn.

I am sorry that we are parting, because we understood each other very well. I learned a lot from him about medicine and how to manage a hospital team. From his speaking, admittedly restrained, as if between the lines, I could only guess something that I would find out more definitely only in 1948 and after.

After his departure, I took responsibility for the further life of the hospital in Pontones. But now in somewhat changed conditions.

Late autumn arrived, and along with it came cold water to our farm, water from the sky and water from the violent Jucar River, which flooded our yard and ground floor rooms every hour. Damp seeped into the sick beds. How will we winter in this mud and November? The patient’s moral thermometer began to decline and dropped almost to zero.

We asked our friend Telge in Albacete whether the hospital could be located somewhere in the Mediterranean. We also found out about a suitable town on the sea coast. We were even persistent in our request. One day in Pontones, Comrade Telge was invited to an inspection to find out what was wrong with us. Unfortunately, as it always happens when the inspectors come, the main arguments fell out of our hands that day. The sun was shining over our hospital and it was dry in the yard!

Telge didn’t even want to hear about moving.

You should stay in Pontones and spend the winter. To think of moving to the sea would mean backing down in the face of difficulties – Menshevism!

My persistence and Telge’s collided, Telge concluded the discussion with a sharp assessment of my attitude.

“You are a young communist, and you are also from Yugoslavia. It’s a shame that you pose the ‘question’ like that.” I will inform the comrades responsible in your party about your attitude.”

Telge touched my pride and thus took the victory. For me, staying in Pontones became a test and a test of my “Bolshevik ” approach to difficulties.

No sooner had Telge got into the car and drove off towards Albacete, it started raining again! We held a consultation on what to do. We proposed the only possible way out: the entire yard and the approach to the hospital were filled with a thick layer of gravel. Gravel had to be brought by one’s own efforts from a distance of about half a kilometer.

At the hospital’s general meeting, none of the patients even wanted to hear about this action.

“We came here to be treated. Digging and carrying sand will worsen our health condition.”

After my declaration that I would go out to the work site tomorrow morning, five volunteers came forward. They were all Yugoslavs! I left the hospital staff to their regular work. The six of us found some wagonettes and some narrow gauge nearby, all piled up like scrap metal. In one afternoon, we managed to mount the track (among my companions were two forest workers from Gorski Kotar, who were very good at this job) and in the afternoon of the same day, a narrow but thick strip of gravel stretched across the yard. It was really pleasant to walk on it while the whole environment was a disgusting mire.

Then there is a change in the patient’s mood. The next day there were more volunteers than tools. Everyone dug or threw gravel for only five minutes, percussively, with full force, and then the shovel would pass into other hands. I still tried to keep the lead in digging. On the third day, the patients chased me away from that job:

“He does his medical work. After digging, when you give us injections, your hands tremble a little. We will finish everything.”

And it was like that. After a week, we achieved the desired goal: the entire yard was filled with a thick layer of gravel. And the hospital team became stronger and merged again into a monolithic whole. Intensive cultural and artistic work developed again. So we overwintered in the Pontones den without serious consequences.

In the spring of 1938, a great danger loomed over the Spanish Republic. A great fascist offensive through Aragon began towards the Mediterranean Sea. A large number of units and institutions had to be evacuated from the central part of Spain and transferred to the north in Catalonia. According to this plan, Pontones was also evacuated.

At the end of April, to my great joy, I got a new position. Dr. Langer, an Austrian, who worked in the Directorate of International Brigades, assigned me to the 15th Corps with the aim of expressing and achieving my basic desire there: to work as a Doctor in a combat unit. I handed over my patients to an old Pole (he was related to the “king of alcohol” and his hands were shaking more than mine after the work in Pontones). The patients protested against this shift, and in front of them I felt somewhat like a deserter.

THE BATTLE ON THE EBRO RIVER

At the end of the Fascist spring offensive in 1938, the front towards Catalonia was established along the Ebro River. It’s a big river, like the Sava near Belgrade. In July 1938, the Republican People’s Army undertook a sweeping counter-offensive. On the night of July 25, 1938, across the banks of this river, on a front about 150 kilometers wide, three of our corps 5th, 15th Corps (both consisted of the most elite units) and 17th crossed suddenly and violently. On the direction of the main attack: Mora de Ebro – Gandesa – Zaragoza, the 15th corps, i.e. the 35th Division, which included three International Brigades, operated: 11th German “Ernest Thaelmann”, 13th Polish “Dombrowski” and 15th Anglo-American “Abraham Lincoln”. In the first echelon of the 11th Brigade was my battalion, called “Hans Beimler”. That battalion found himself at the very top of the huge wedge, they were forming the Army of the Ebro.

The battle on the Ebro River lasted a total of 115 days. Already after ten days, it became clear that the basic goals of this battle would not be achieved. However, the general strategic goals of the Republic demanded that the battle be prolonged. The Ebro Army fought a much superior enemy for another 105 days. They fought knowing full well that there was no prospect of achieving the initial goals of the offensive, knowing full well that even the captured area would not be able to be held, they fought for the highest military and political interests of the Republic. Awareness of the operational senselessness of the battle and awareness of its strategic and, so to speak, national sense, this completely contradictory awareness permeated the entire composition of the Ebro Army for a full 110 days.

LIFTING TO THE RIVER

From the reserve positions, around the town of Falset, the 11th Brigade overcame the dry and narrow mountain ridges during the three-night march to the Ebro and slipped unnoticed into all the barrancos[5] that flowed from the mountains to the left bank of the river. Barranco de los Corraptes! Despite the terrible name, this barranco was one of the good ones: vineyards, figs, olives and wells. The brigade ate, fell asleep and soon forgot about all the hardships it had endured during the previous three nights and three days: the soldiers falling apart from fatigue and fever (someone in the Supreme Medical Command thought to order a general vaccination against typhus on the day before the movement towards the Ebro! (Gross tactical error). Then the angry statements of the German comrades when clearing the congestion on the roads, and curses. I found it difficult at first. Why do they have to swear and scream so much? Then I forgave them as if they could not do otherwise. The driver fell asleep in the cab in the middle of the road, there was a column on the road, an ambulance with patients was trying to get through from the opposite direction. Gathering in the pitch black, and even a pocket battery must not be turned on. How are you going to do it now if you’re not going to run over a fighter who’s stretched out on the road in a deep sleep? How are you going to do it if you’re not going to swear and shout: “Vorwärts! Vorwärts!”[6] and I am glad that this word is heard on our side and that someone of ours has it who pushes and pulls this force of ours forward.

Before evening, my Battalion was given the task: during the night, to cross the river upstream from the village of Asco, drive out the outposts, destroy the enemy, capture the high ground, etc.

There is also Major Dr. Arco, a Romanian {Leo Arco, 545/6/669/1 – rmh}, the head of the Brigade’s Medical Department. That tame and cold-blooded fellow came to give me instructions for tomorrow. We went to the hill to scout the enemy coast.

The shore of the enemy!

I’m shivering. Is it from the vaccine (which I injected myself with in front of the battalion machine? to show with my example how it’s “nothing”, or from excitement?) And here, what I see. Actually I don’t see anything special. just as I recently read the legend under one photograph of the battlefield in front of Brunete: “the characteristic of the modern battlefield is that nothing can be seen”. My eyes dart from the left to the right to the edge of the horizon, the river seems to be asleep, a band of willows on a shallow muddy bank on a slight rise covered by a vineyard, the village of Asco on the left clings to the river below the slightly steeper bank of the road. No one alive anywhere, except that a mule with a two-wheel cart is moving calmly along the road on the bend above Asco. A peasant on a two wheel cart. Is that the enemy? Arco explains to me:

“The evacuation of your wounded will be supported by the Brigade Company of stretcher bearers. There is nothing else I can do, because tomorrow the ambulances will not be able to reach the other shore. I wish everything turns out well for you. Healthy and happy.”

FIRST MORNING

In the first dusk, the movement towards the coast began. About half a kilometer before the river, my Commander, Major Mirales, a Spaniard {maybe Miguel Jose Miralles, 545/3/669/43}, said to me:

“Stop here and wait for my courier.” The Battalion immediately crosses the river. “There probably won’t be any wounded and don’t approach the river without my order.”

We found a stone house in the olive grove. My paramedics were immediately overcome by sleep. I let them sleep because, I reckoned, it will be good for tomorrow. In war, you should use every moment to sleep. They were honest comrades on whom I could rely in everything: Albert from Switzerland: Peter, a German with a yellow mustache threaded à la Kaiser William; Abundio, a Spaniard, and Leo Mendaš, a student from Slovenia.

Time passed in silence. I was overwhelmed with worries. How are we going to cross the river? Swimming or floating? And what if Fascists are lurking on the other shore, while we are on the water? Maybe they already know about everything we are preparing? What did the Russian adviser Grigory say at the meeting of all the officers of our Brigade just seven days ago? He presented the topic “Forcing water obstacles” and at the end reminded us to keep military secrets. Even then, I winced a little at his sarcasm: “And now, look at that road above Falset!” Trucks transport boats from Barcelona to the Ebro in broad daylight. Is there such a “fool” who wouldn’t understand what it was about? Indeed, I also watched those boat processions for several days, but I must say that I was one of the small number of “fools” who did not even think that our offensive was being prepared. So said Grigory, a calm and composed Russian adviser, tall as a mast, with a handsome and furrowed face like Kirov’s.

What if his premonitions come true?

Suddenly, after several rare gunshots and explosions, the front in front of me goes up. Is it already a fight or a random shooting in the middle of the night? Rare beams of luminous bullets whizzed high above us. There is no courier. An empty space darkens around me, I no longer notice any movement, as if the entire rear has become empty, as if the last fighter has gone forward and found his place in the general assault, and we, the paramedics, seem to be forgotten and redundant. Thinking that there must be wounded people in that hell ahead, a restlessness grew in me that fought with sleep and fatigue from tense anticipation. I am sending a paramedic to get in touch with the Battalion Headquarters. But he is not coming back either. “To hell with my staff and this whole organization,” I protest to myself. Then the fire started to die down. I decide to move forward. Arriving at the shore, some sailors told us that we had to go upstream for quite a long time, because the place where my battalion is crossing is much further up. We now had fire from the left flank on the other side, but it was rare and disorganized; we could only feel it by the whistling of bullets and by the willow branches that, cut off by the branches, fell on us.

In the air, in the sky, you can feel the beginning of morning. I’m already starting to tell trees from people. Sleep crisis again.

On the bank, at the crossing point, in the crowd, Commander Miralies was the first to recognize me. He exclaimed and hugged me:

“Well done, Medico, you came at the right time!”

“Are there any wounded?”

“There are none. Everything is going well. The battalion is already on the other bank. We drove the “guys” out of the first trenches and now the fight is on for those about one kilometer deep. Jump into the first boat.”

The morning is still coming. Pale blue and rebellious. Before long on the shore itself, commotion. Splashing water and dull blows in the boats. As far as I can make out people, it seems to me that most of them are hanging around and don’t really know what they are doing. Caustic ammunition {tracers?}. The only sense of meaning in the line, which, from hand to hand, loads the crates of ammunition. I’m waiting for an empty boat and in that waiting, comparing myself to my friends, I felt unemployed and therefore redundant. I want actions, just any actions! There are no wounded. That’s why I run without any goal. How well it’s all going for us… Something is choking in my throat because we’re doing well and there are no wounded.

We left the shore, and behind us, something downstream, someone cried out desperately: “Los remos! Donde están los remos?”[7]

“What is the meaning and what are the consequences of someone raising oars to someone?

Don’t ask, go ahead!”

Now something happened that seemed completely impossible to me, as a war novice: we found ourselves on the mirror of the river, in the “wiped space”, about which I had previously only heard from the old warriors, twisting and crawling. But what do you do in a boat that is full of fighters and preparations? Is there a chance that it is not a target for the enemy but a boat on the clear glass of the river? The dawn has already broken in a big way. Now it is a pink sunrise. The enemy is on the high ground, although already amused by the fight, he could clearly observe and guess.

The machine-gun spray went off. For the first time in my life, I saw the roar of small waterfalls in the river around us. “So that’s the war!” I remembered my fellow villagers’ stories about the crossing of the Drina in 1914. There were many deaths on the Drina. Will it be the same this time? Is it possible that things will be different now? Leave the boat and dive under the water like a pond grebe? But all the people around me were apparently calm. They were just looking ahead. I pulled myself together and gave myself an order. “Enough with these fantasies! Don’t think about anything! Stop thinking! Stop thinking and just look ahead! Think only about getting to the other shore, that everyone is watching how you behave and that you must not embarrass yourself. Go ahead to the other shore!”

Today I present these elementary psychological details as an experience and a lesson on how, through a certain conscious process, the state called war rapture is reached, in fact a state of reduced awareness. The closer we got to the shore, the deeper we went into the blind spot and the more and more bullets were thrown over us (lesson: boldness and persistence reduce danger, and hesitation is ruin).

In a rush, we dock along the muddy coast. No one was injured!

But what is happening in front of us?

Through the middle of the willow forest they carry someone in their arms. He stopped in front of us. I see Karl Ernsteta’s {believed to be Karl Erik Georg Ernstedt from Sweden who died in the Cave Hospital at Falset?} pale face, as pale as the morning. The tame blue Commander of the Scandinavian Company in my Battalion. The first bandage came off his chest and through the gaping wound the size of his palm, I can see his heart beating. The young Commander struggled to catch the fresh morning breeze. Open pneumothorax! I did for his life what I had read a few days earlier in a Spanish manual, the only thing I could do: I put over and covered the wounds with thick layers of gauze and glued several generous strips of leucoplast over everything. The Commander was immediately transported to the other bank, and I, with my paramedics, extended the front line to meet it.

The first day (July 25, 1938) About a hundred meters from the banks of the Ebro, behind a belt of willow thickets, we came across a vineyard and rare machines. Even further towards the front, the hill on which the fight was going on stretched, a little more calm. The fire seemed to originate only from our units, because no more bullets came from there.

I wanted to develop a changing center in a lonely field house. My paramedics, like experienced warriors, dissuaded me from this intention:

“The house will be pounded by artillery and aviation. Away from her!”

We set up under an olive tree in the immediate vicinity of a deep trench in which the “Fascists” were until a while ago. In the trench: a few empty shells, a box of ammunition and all kinds of other things in a mess. That means: they broke off suddenly. For the first time then, I also experienced some a strange feeling that followed me throughout my war every time I stepped on “enemy” land, newly liberated. Feeling curiosity, disgust and fear at the same time. “That’s where they walked a little while ago”. Paths, trenches, objects, barracks, and even entire settlements, all this beckoned to be looked at, touched and searched, in order to determine if it was the same as ours or if it was very special, significantly different, “hostile”, stronger than ours and still dangerous for us. As if they are still there.

A small group of wounded men was coming down the slope. With the exception of Karl Ernstedt, whom we instantly and silently encountered on the shore, these are our first wounded. The wounded! Excited, I run in front of them: as fast as possible, as fast as possible to them, as soon as possible to do something for them. Look how well they hold! One cheerful, the other seriously calm, but no one, absolutely no one moans. And why would you? The boys performed the task properly, “they did their best”, they were greeted by the gaze of their comrades who continued the fight and now, here in the infirmary, on the way to the rear (a dream of sleep and rest) there is nothing more to desire, because honor and glory have been gained; what is physical pain compared to that satisfaction, and even less to complain about anything except for the comrades who remained to shed more blood. The comrades remained. That is why the wounded of this moment are both sad and will immediately, as soon as the wound heals, leave the rear and all its good and bad things and return to this world of purity, clarity and familiarity. We accept the wounded: some give them water, some wine, some a crate of ammunition to sit down and rest. Comrades, quickly bandages, give it quickly!

Then send him to the shore, in the boat.

We learned from the wounded that Vigo Peterson, a red-faced, thin guy, still a boy, a medic of the Scandinavian company, the best medic in the battalion, had died. They said that he got hit right in the throat and stayed in place as if he was lying there.

I’m in a sort of frenzy and I barely manage to, in the hour before my breath, surveying the whole environment, understand where we are and what’s happening around us. The fire on the front of our battalion, on the hill, was moving somewhere in the depths, barely audible and already muffled by the breaking color on our left flank. At a distance of about 1 kilometer to the left, I see the village of Asco, illuminated by the first sun, squeezed between the river and the high bank, house to house, house above house, all round like a laid egg, and in the middle a church tower. Our artillery is firing from the left bank, enveloping the village in smoke and dust. Machine gun barking woven into a single thread. The “12th February Battalion” is there, Austrian, which means that Asco must fall. Behind us, on the left bank, just now you can see the smoke, the land rises abruptly like an escarpment or a palisade. Who knows, the area where we gathered this morning to board the barges must be quite narrow. I don’t like tight spaces. I have no contact with the Battalion Headquarters. I conclude: this place where we developed a changing center belongs to the narrowest belt on the even the bridgehead. Cabeza de puente!

The day dawned. One of those days in life that seem endless to us, that they cannot be survived, or, if they are survived, that then they will live forever. First, from somewhere in the depth of the enemy, several shells whizzed over our heads and exploded on the left bank exactly at the boarding point. I winced at the thought of Karl Ernstedt and the other wounded, if they were still there. The cannon soon fell silent.

Then the main thing started. The first scout plane appeared. In a wide zigzag circle, he nervously flew around the entire battlefield around. Searching along the river, down the river and disappeared. My paramedics knew but what will come after him:

“Ljegaran las pabas.”[8]

Really. Around 9 o’clock the sky thundered from the west. In these formations, the planes covered the bridgehead. I count: five, ten, fifteen, thirty-five, fifty, paba”.

They are still just circling, sort of lazily and, regardless of our anti-aircraft artillery, they are still in their perfect order. More

Awaiting evacuation

I have time and patience to observe their shapes and colors. They all seem huge and sluggish to me, some dark-colored, others with greenish-blue, almost transparent wings like those of a fairy horse {I think he is referring to a dragonfly, not to the literal “orko” or mythical being – rmh}. It means that their main goals are boats, rafts and a bridge which, as we heard, is already being raised lower than Asco. Our dressing station is in that circle. And now the show can begin. Without falling and continuing in circular horizontals, the “pabas” simply got rid of the load of bombs. With small interruptions, it lasted the whole day until sunset. The most difficult for me was during the breaks when there were no wounded, when there was nothing to do and when a man had nothing left, nothing else but to fall down in the trench and to look with envy at the ant that, in the end of the world , carelessly pulls its straw.

I envy an ant now. And then I felt the earth in a new, previously unknown way. The Earth literally breathed, as the waves of the sea breathe.

I only longed for a wounded man to appear. I was grateful whenever one came. Is it selfishness? Out loud: Ljegan los heridos[9], we jump out of the trench, shake the earth off our face and, look, this whole horrible reality becomes bearable, you don’t stop caring about yourself, you part with your personality and identify with the wounded.

We were angry with our anti-aircraft artillery. Although the sky was almost covered with whitish clouds of smoke from the exploded shells, still, as if some kind of stronger fate was directing this event, we could not see any plane in flames. The “pabas” were still circling motionless, as the heavenly bodies circle, submitting to laws beyond the reach of men. This comparison with the heavenly bodies filled me, along with all other evils, with a feeling of bitterness and impotence, but I could not avoid it. And, at last, to bring our anger to a climax, we were threatened by our anti-aircraft guns, and we ourselves more than, as it seemed to us, Fascist planes! Namely, fragments of exploded shells fell from a height of 3000 meters causing a rustle in the air as if a flock of pigeons were flying. But behind this idyllic comparison of wings was a great danger to the people on the ground. We had to put on our helmets.

Asco fell around noon.

Nothing to do with headquarters. The bombing continues until dusk.

Then everything went quiet. The silence lured people out of the barrancos and trenches. Couriers, quartermasters, telephone operators and reserve units started to move, and in this apparently chaotic confusion, everyone contributed in their own way to the preparations for tomorrow’s battle.

And us?

We loaded the material on our backs and went in search of the Battalion headquarters. We found it under a tall dry medina, not far away, only a few hundred meters from the dressing station. Commander Miraljes explained to me on the map tomorrow’s task of the battalion: the movement towards the village of Fatarella and the clearing of any remaining enemy groups. The Battalion will leave tonight.

“You sleep and leave early tomorrow. Here is the main axis step of movement (la directrica general del movimiento): constantly to the west, parallel to the mountain Montes de la Fatarella which will appear on your right. Do not go too far to the right under the mountain but due west, in the middle of the entire space between mountains and roads from Asco-Gandesa. Listen to the fight and follow up after us.”

“Entendido!10

In fact I understood very little of what awaited me the next day.

___________________ 10 Understood!

Second day (July 26, 1938)

The very dawn indicated that this day would be unusually hot.

We set off with our equipment in the direction that Major Miraljes told me, more precisely, the direction that, after last night’s instructions at headquarters, I had created in my imagination. I have neither maps nor sketches in my hands. I am orienting myself only by the sun, which beats mercilessly into our backs, by the land that gradually rises, and by the echoes of rare bursts from a great distance. All other elements are the result of free reasoning or imagination. Still, as long as I hear the fight, I reckon, I’ll be sure I’m on my way.

Immediately after sunrise, the aviation continued its work done yesterday. Endless circling over the Ebro and dumping bombs. We don’t even look back at the planes anymore. Now it’s just bothering the people who build bridges. In addition, someone said last night that the Fascists could open large dams in the upper reaches of the Ebro and release huge amounts of water. A flood can wash away all bridges, rafts and boats. Does anyone think of that danger?

They are carrying a wounded man on a stretcher to meet us. Femur fracture. Spanish. Proud and painstaking. The wound is very large, caused by an explosive bullet. The wounded man says that there is no longer a front or an organized fight. He was wounded by a group left behind, from an ambush.

“Carobnes”[10] said the wounded comrade.

Bandage, splint, anti-tetanus serum and, finally, salud comrade, mucha salud! The heat is growing, and the sizzling of the buzzers is penetrating the brain. Rare, very rare olive trees begin to flicker from the glow. In front of us is a bare hill, and on its top, in contrast to the whitish sky, we saw a dot, some kind of black object that strangely floated above the horizon, as if it was suspended by some invisible rope. It was only when we were close to the object that we realized its nature. It was a corpse. A corpse on top of a cuckoo. The corpse was dressed in black chakshiras {??} and a black shirt and was all black from rotting, tense and huge in the pose of a “sleeping giant.” He apparently fell yesterday morning. Whose is it?

From the high ground, we saw an undulating area that split in front of us far to the west, an area limited by a mountain range only on the northern side. Judging by the map I saw last night at headquarters, it could be Montes de Fatarella.

No one anywhere. No sound of weapons, no calls of people. Just kill the exact noise of the buzzers, the thunder of the bombs behind the rocks and the hugean apparently empty, heated space in front of us, which makes me feel uneasy. Where is the Battalion? Where is anyone? Discomfort from feeling lost, lost and redundant. Eh, we are also part of your “order of battle”.

Maybe we left late, moved slowly and therefore, through our own fault, lost contact with the Battalion? Maybe you should hurry with all your might, keeping to the given “axis of movement”? But, what is the axis of movement in this case? It is neither a road nor a mountain ridge, but an interspersed, furrowed space that we can’t stop staring at. On such a terrain, you can walk past the battle without even seeing it. After all, it could be that the Battalion is now living in a dead sleep in some shady barracks, and we are breaking cover without any sense. That thought seemed pleasant to me and, once I got hold of it, I made the decision that it is best that we too look for shade and rest somewhere! At noon, we passed by the Fascist artillery camp. One 75-millimeter gun was still looking towards the Ebro with its throat, but now immensely powerful, in the middle of the general rubble of crates, scattered straw ammunition. Bites of “corned beef” from a can and sips of disgusting bland water from some kind of well in the vineyard. I wanted to lie down in the straw for a bit, but my paramedics stopped me:

“No, it must be full of lice.”

We slept for a good part of the afternoon. I don’t know if we were awakened by our conscience or silenced by the thunder of cannons that we listened to from a great distance with our ears close to the ground. Where is it from and what is it? Direction: southwest. Southwest? It means that it is neither from the Ebro, nor from the direction of our battalion. It can only be from Gandesa. Is it possible that some other Brigades are already fighting for Gandesa, while our Battalion is hanging around this desert without contact with the enemy and while we, in search of the Battalion, are thinking about what to do, instead of all of us already being there, or at least on the way to Gandesa? We have decided to slightly change that famous “axis of movement” on our own and at our own risk, to the extent that we will turn a bit to the left, towards the southwest, so we will, we calculate, break out onto the Asco-Gandesa road. And on the road, we will get closer to the battle faster than if we break through this dead road. After all, we will no doubt come across many units on the road and find out where our battalion is. At the end of the day, I guess the battalion itself will have to hit the road somewhere, Gandesa is our main goal for now.

We hit the road in the evening. We found that we are not far from Asco. A whole day of marching, to determine the result of only five useful kilometers in the direction of Gandesa at the end of the day! We spent the night just above the road at the oblom {dead end?} bare hills. Another night in half sleep (every hour I twitched and asked myself: where am I?). The night ended too early in the morning. Movement in primeras luces del alba.10.5

Third day (July 27, 1938)

All my predictions yesterday turned out to be correct. No, I don’t find satisfaction in that, on the contrary, there is no end to my anger. Yesterday afternoon, the Battalion turned its “axis of movement” to the left and broke out on the Asco-Gandesa road, but much earlier than us and much closer to Gandesa! There, on the verge of an important strategic crossroads, called Cruces de Camposines, the Battalion was stationary yesterday camped, slept and stayed at an ancient home. And we, if we had consistently followed the orders that Miraljes had given me the day before yesterday, we would still be roaming the hills around Fatarella, ten kilometers to the right of the main line of action of the 11th Brigade.

I reported to the Headquarters and kept calm without asking for any explanation, although the question was boiling inside me and pounding in my temples: why did they send us where we didn’t go ourselves? Why did we even have to move separately and at such a distance from the main part of the Battalion, when the rule of the service dictates that the paramedics march, admittedly, “at the back of the column” but as part of it? What would have happened if the Battalion on the march had been surprised by aviation ? Who would take care of the wounded? Does Batallion’s headquarters not know the elementary rules of tactics, or does it all have some special meaning? Why, at least now, no one at Headquarters asks me how we did today? Wasn’t that Commissar Dominguez’s duty? While I spoke with Commander Miraljes, Dominguez was typing on a typewriter. And a topographer! That man gets on my nerves from the first meeting. An Argentinean, who speaks German fluently, handsome, always in an impeccably tight uniform. I can’t stand his Somiar yellow leather boots, I can’t stand the fact that I’ve never seen him at work. And now he was freshly shaved (yes, he’s the only one in the entire Ebro Army these days who has the time and opportunity to shave) and now he was sitting on the ammunition box, calmly smoking and, it seemed to me, looked at me cynically. But, maybe these impressions of mine are more the fruit of my skeptic, suspicious imagination and nervous overexertion? Still: why couldn’t a fellow topographer make sketches of this terrain to make it easier for us to move? That’s his job.

I didn’t even complain to Dr. Arco, the Brigade Doctor, when I saw him riding next to us on the road towards the Camposines intersection. Good Major Arco. He was riding on a small mule, bareheaded, in a shirt with rolled up sleeves, without the marks of his rank and, as his feet were almost dragging on the ground, he looked like Jesus to me! He stopped in front of me:

“But is everything going well?”

“It couldn’t be better.”

“How many wounded did you have on the Ebro?”

“About a dozen. I don’t know about the dead.”

“And yesterday and today?”

“No one… except me…”

“What happened?”

“No, nothing, I was just joking.”

Arco grabbed his saddlebags, handed me a can of meat and walked towards the intersection.

Now I could pay attention to the events around me. From the pine or olive grove, where the Hans Beimler Battalion was encamped, the road gently descended for another three kilometers to the Camposines intersection and from there, almost in a straight line to the southwest, it stretched towards Gandesa. To the left, along the entire road, from the Camposines intersection to Gandesa could see the ridge of a ridge that became darker and more inaccessible as it moved further west. However, for me, as before, it was an extraordinarily exciting picture of war that now appeared to me. The entire valley, on the left and right sides road, it was pressed by thick layers of dust and smoke through which, here and there, the rays of the setting sun broke through, illuminating the valley and the mountain slopes with sometimes purple, sometimes blue, and sometimes yellow spots. One could dwell on the beauty of this picture for a long time what if its creator were not war.

War.

“Artillery Duel.”

This is what war looks like in one of its countless forms. This time, for me, who was watching this artillery duel from a distance of about five kilometers, the war seemed to me to be lighthearted, almost romantic.

Grenades from one and the other side were falling systematically, relentlessly, and somewhat lazily, as if they were already bored, but since my battalion was out of their range, this duel seemed to me like an interesting game. The first and, hopefully, the last time I felt artillery fire like that!

Movement towards Gandesa. Tonight, we also enter into a fight, this time much different, more difficult than the day before yesterday on the river. Now we won’t be able to use surprise anymore. Here is an enemy after his retreat from the banks of the Ebro, he managed to settle in Gandesa for the winter. Our 13th “Dombrowski” Brigade, they say, bravely made its way to Gandesa on the first day, but, not having any heavy weapons with it, had to stop there. The town is being attacked tonight and our entire division with its three Brigades needs to occupy it.

Fourth day (July 28, 1938)

During the night we passed the village of Corbera, destroyed, dead and with the bloated corpses of mules and horses on the main street. There are still four kilometers to Gandesa by road, but our column will turn right, on the initial field road. Morning is outlined by the hilly edges of a long valley, Barranco de Valdecanalles. One of the barrancos that will remain in the permanent memory of the 35th Division. Barranco feats and hopes, barranco many deaths and the bitter knowledge that our offensive power has come to an end.

While the column was moving across the plain, the enemy spotted us from the heights on the left and rained heavy fire on us. Explosive bullets break olive branches. We run across the field to the left, soon we reach a blind corner under the hill. The Battalion ran up the hill and soon joined the general attack that had already begun. It seems to me that we are a little late. We developed a dressing area under a stone wall and, while there were still no wounded, we dug a protective trench. I am leaving for a few hundred meters by the barranco to consult with Doctor Lenhova, the Doctor of the neighboring Battalion, “12th February”. We agreed to bandage, each in his place, every wounded person, as he came across, regardless of which Battalion he belonged to.

The fight broke out on the entire sector of Gandesa, in a half-circle ten kilometers long. Thousands of rifle and machine gun shells buzzed above our heads and disappeared somewhere in the hill in the opposite rampart of the barranco, while many mortars flew over the hill, exploded in the plain next to us, and I was happy that that huge amount of steel did not hit the fighters in position.

Wounded people also started arriving there, not individually, but in a continuous flow. We print a wounded card for everyone (copy remains with us). Those who can move well and the first dressing fits well, we send them immediately further to Corbera, where the Brigade has set up its dressing station on the western outskirts of the village, in the olive grove. We put new bandages and splints on the more seriously wounded, give them drink, anti-tetanus serum and morphine. We had enough morphine, in tinfoil tubes, on which a sterile needle was already attached.

Behind the front line

In the afternoon, the fire reached its peak in the sector of our brigade. Mortars are especially active. Now the wounded are coming down the hill somewhat hurriedly, almost running. There was some unrest upstairs. It seems that the Fascists have counterattacked. Will we last until nightfall?

They are carrying someone on a stretcher. This is the Platoon Commander in the Third Company, a Spaniard. Under the helmet, I recognize his black, thin, almost ascetic face. He is now in a deep unconsciousness. The bullet pierced his helmet and skull. The wounded man was breathing very slowly, deeply, laboriously and with longer interruptions. Cheyne-Stokes type of breathing. A very bad sign. A symptom of severe brain injury. There is no more help for him. We kept the wounded man next to the dressing table, in the shade of an olive tree, to wait for his death.

The pace of our work is constantly increasing. There are not enough of us for this much work. Now I can only allocate actions to my nurses. “Abundio, put a splint on this, Alberto, give an injection of morphine here, Leo, loosen Esmarch’s curtain!” Leo is my right hand. Actions become automatic, we don’t even feel what is happening around us, my head is pressured by the forced repetition of the term, “Cheyne-Stokes, Cheyne-Stokes”.

The momentary interruption in the arrival of the wounded brings us to the ground. Let’s just wipe the tarry sweat from our faces and rinse our mouths.

But in that, a terrible scene appeared to us. In front of us stood a scarecrow of a man. In the place of the former human face, there was now a huge bloody hole that drained just below the eyes. The remains of the lower jaw hung, like an apron covering the upper third of the chest. Blood and saliva dripped down the entire body of the man who stood before us upright and speechless.

I recognize Emil. {An Emil Neilsson was killed 7/30/1938 – 545/3/74/45 rmh}

I recognize him by his huge stature and by his eyes, very meek eyes, with which he stood out from all his compatriots (Look, a German, and a meek one). Veteran, warrior, still in the First World War. He told me earlier about the horrors at Ypres, but even then, while he was talking, he was smiling with his face and eyes. And now, while we are strapping his broken face, Emil is smiling with a smile that he doesn’t have, that he will never have again. A smile of satisfaction, but only with the eyes: I gave everything now. The one at Ypres in 1917 was Scheisse.[11] And this now makes at least some sense. It makes some sense. We bandaged the wound, gave him an injection of atropine and, after the rest, I gave him a paramedic to accompany him to Corbera. He refused. Showed him the nurse and twirled his hand around his arm. He wanted to say: Let the paramedic stay. He needs to bandage.” He left accompanied by a slightly wounded man. Farewell, Emil, farewell soldier of the world revolution and defender of the honor of the German people!

The Platoon Commander exhaled. We buried him under an olive grove. Before nightfall, the battle temporarily calmed down. No results for either side. It bled out. I sent a report to Headquarters: 60 wounded in our battalion.

Twelfth day (August 5, 1938)

On that day, the 11th “Ernest Thaelmann” Brigade was withdrawn to rest and reserve. From the day it arrived in front of Gandesa (July 28), the Brigade, without a single night of rest or sleep, was thrown from one skirmish to another. Just when they would attack on one wing of the Divisional front, immediately afterwards it would have to transfer most urgently and feverishly to the other wing in order to close the suddenly created and extraordinarily critical breach there. In doing so, wonderful examples of solidarity between all units were manifested. And in the units themselves, in the fire of day and night battles, the process of their internal hardening was fast. The young Catalans, newly recruited before our offensive, mingled with the old warriors, competed with them: and not infrequently took the lead in bravery. Bravos muchachos![12]

From the crossing of the Ebro (July 25) until August 1, the Brigade had about 400 wounded and dead.

But we could not take Gandesa.

And the enemy was bled to death. With the day and night attack of our divisions, we did not manage to move them even an inch, but they managed to hold Gandesa. And, in addition to that, the enemy brought in and piled up every day new resources of material and manpower. We didn’t have them, or hardly anything.

Noting all these facts, the Command of the Ebro Army concluded already on August 1, 1938, that there were no reason for the extension of our offensive, and that the second phase of the battle was coming, a persistent defense with the aim of extending it to occupy the area. The general command of the Republican People’s Army also demanded that the great bridgehead in the narrow bend of the Ebro destroy, attracting, pinning down and exhausting a hundred and more of Franco’s divisions, with the main goal of relieving the rest of Spain’s fronts and thus gaining time to achieve some more significant change on the International level. In the aid of such goals, and not achieving the capture of Gandesa, it was necessary to continue with constant counterattacks, especially night (golpe de mano), and above all, it was necessary to interweave the entire terrain, along the front and in depth, with a network of trenches. That’s how the slogan was born: “Fortificar es vencer”12.5. The slogan never left the minds or the hands of the Ebro fighters. Before the will of the men to dig in, to resist the superior technology, the very rocks of Sierra Pandols, Sierra Caballs, Gaeta and terrible hill 565. On those slopes, raging in continuous waves for a hundred days and nights, the most elite troops of Spanish and International troops melted.

The Brigade camped in the Barranco Bremonosa area, about eight kilometers behind the front. Neither the thunder of airplane bombs on the bridges of the Ebro, nor the fight, completely foreign, on the front, nor the battles in the air between us and the enemy’s aviation (after all! what a pleasure it is to watch the glimmer of aluminum in the atmosphere and the flames of Fascist planes falling!), nothing is could disturb our feeling of absolute and well-deserved silence in the barranco.

Thirteenth day (Barranco Bremonosa, August 6, 1938)

The mobile bathroom and the same laundry went away. For one, we bathed and changed. Bliss.

The fourteenth day (Barranco Bremonosa, August 7, 1938)

Now we can already remember the past and think about what has been done. Some bitterness came to my throat. I search myself, did I not get too carried away by impressions, by my heart, by a dream about people instead of relying on facts and on people as they really are. No. The facts are still there: they stayed with us all night on the left bank of the river; they left us on the second day to wander on the empty road, and later it turned out that the enemy’s units were still wandering through that terrain, broken, but ready for anything; on the seventh day, around midnight, they ordered us to come to the machine gun, because allegedly, there are so many workers that there is no one to bandage or evacuate them; when we got up, it turned out that there were no wounded, and on the way we ran into the densest mortar fire, the likes of which I have never been in before or since.

Why all that?

I go to headquarters. There was no Commandant Miraljes whom I loved, because he was good natured and honest, although, it seems to me, he did not understand the essence of medical care, and maybe he simply did not even understand it. I found Political Commissar Dominguez and, of course, the topographer. This time, the topographer shone with external neatness and cleanliness. His idleness and his perfection bother me. Perfection in dress and perfection in knowledge of the German language (and he came from a Spanish speaking area). I’m bothered by his attitude of a fiddler and a cynic. I doubt him and subject him to suspicion in myself. Was I right? Is it all his fault that he doesn’t fit my scheme?

But Dominguez?

I ask myself, do I have anything a priori against him? No, nothing at all. On the contrary, I really like the character: thin, long face, beautifully sculpted lips, sharp, sensitive nose and thick hair. He looks like a bullfighter. I also like him because I always see him busy. In addition, without any doubt, he is also a Communist.

“Camarada commissario!”

“Si, doctor!”

We moved a little to the side, although I felt the topographer was among us. Just the thought of him like that puts me in a state of reduced self-control.

I presented my “points” to Dominguez. I couldn’t hide my anger and he grew with every word he said, and finally condensed into a protest:

“I am a volunteer and I came from a great distance to defend your country! I don’t allow such actions!”

Dominguez could barely wait for my last word, then burst into fireworks:

“Volunteer! That word is not a phrase that you want to turn into. International volunteer! That word obliges you a thousand times more to respect your Officers and to be disciplined. . .”

“What do you say? Give me a single example that I was before violated discipline, that I did not carry out the order. What would the hundreds of wounded people who passed through my hand these days say about that? And I’m still forced to run after you like a dog! (como un perro).”

“Bastante![13] It’s not the first time I listen to your lectures and phrases. I remember in Falset what you said about the opportunism of our headquarters . Nada mas.”[14]

Dominguez jumped off the ground and walked away.

So here we are. Everything is clear to me now. “Opportunism of the staff”. I also remember that meeting well, but I never imagined the consequences of my criticism. It was in the bivouac near Falset, at the beginning of July, before our offensive. The bivouac was full of flies, they did not have bathing pits and the Battalion had dysentery. I repeatedly reminded them what needed to be done, but things went on as before. Then I spoke at the headquarters meeting:

“Dysentery will ruin us. It’s not my job to clean toilets. We just meet and talk. You should do, not talk. This is called opportunism.”

So, everything I experienced these days on the Ebro, it’s all some kind of retaliation for criticism? Retaliation for an insult to the superior’s vanity? Is that possible? We are brothers in ideology, we are one, and yet there is something that separated us, me and Dominguez, something that is deeper in people and currently stronger than common goals.

I felt crushed, and yet, I understood this “conversation” with Dominguez as a deep lesson: not everything is in the essence of the thing you present. The essence is also in the way you present it. Sometimes the essence needs to be wrapped in three sweet wafers, or uttered between the lines. It’s sad, but it has to be reckoned with in order to move forward.

Seventeenth day (Barranco Bremonosa, August 10, 1938)

I explained my troubles to the deputy Brigade Doctor. He understood everything quickly and promised me that he would transfer me to another battalion.

That day, the entire area where we bivouacked was hit by concentric howitzer fire. They brought a wounded man to our shelter. I was overcome with excitement when I recognized him as my friend Sveta Popović, the editor of NIN. The shell tore his shoulder blade. A few moments before Sveta was wounded, he and his anti-tank battery took a position just above our shelter.

Nineteenth day (Barranco Bremonosa, August 12, 1938)

The order arrives that I have been transferred to the “12th of February Battalion”. This is the Battalion in which, in addition to the Spaniards, all the volunteers from Austria are grouped. The Battalion bears the name of the date from 1934 when the Viennese workers rose up in an armed uprising. With much sympathy, I remembered Erenburg’s passionate brochure about the Vienna Uprising. What awaits me in that unit? With a heavy heart, I left Leo Mendaš and the other comrades in the Battalion Sanidad. Our relations were, at least for me, impeccable.

Battalion “12. February” was also on rest, not far from “Hans Beimler”. While the artillery was randomly, and already tired, roaming around, the Battalion Commander, Willi Benz, stood upright on the edge of a high cliff. Willi Benz, German. At first, I was a little petrified when I stood in front of this phenomenon: a middle-aged, with dahlia green eyes, a sharp nose and pursed lips. A true Prussian. But the most Prussian of all Prussian things on him was — the cap! He was the only one, among all the Germans of the Ebro Army, who had an officer’s cap shaped in the Prussian way: its front part rose like a pyramid, a foot higher than our caps, and on the top of the pyramid there was a five-pointed star!

I introduced myself to him in a strictly military manner. It seemed to me that he was satisfied with my performance. We sat down. We were silent for a while. The Commander drew on the ground with his stick. Then he spoke.

“Ja”[15]

And I replied:

“Ja!”

Silence again. I notice his oblong face, somewhat haggard, and blue-green eyes, unusually, quite unusually mild. Finally, Willi introduced me to the situation in the Battalion with stingy but precise words. We will stay like this on rest for a few more days. and then we have new tasks ahead of us. He also showed interest in my past work and life.

Willi finished:

“I wish you to feel good in our battalion. I think we will get along well in everything.”

After parting ways with the Commander, on the way to the Battalion Headquarters, I couldn’t find my way: what is this now? For the first time, I experience a Senior Officer sitting down to talk to me, to acquaint me with the situation in the battalion and on the front. And finally, welcome me! My first impression of Commander Willi began to change rapidly. What a contrast between his external appearance and his interior. In fact, we are starting to have such people in our ranks. The precision, calmness, military openness and humanity of Willi’s “cool night”, let them be the antithesis of familiarity, chatter, detention for petty mischief.

I found everything in the best order in the Battalion medical center, buried deep underground, in the steep bank of a ravine. Doctor Lenhof had already left for another duty, and he was represented by Walter Vahs, a physician from Vienna, a Communist, a very loyal friend and a skilled medical worker. Five more brave Spanish young men and there is a team that will resist all temptations in never-disturbed camaraderie and brotherhood during the upcoming battles on the Pandols and Caballs Sierras.

And Willi Benz continues, as during our first meeting, to always remain composed and calm, always willing to explain both news, always interested in whether “everything works” well in the infirmary and with the wounded. In moments of calm in the sector of our Brigade, I would gladly go to the Headquarters. I sat next to Willi on a stone to watch the artillery fire, or aerial combat. We also had a conversation:

“JaI!”

“JaI!”

I will be under Willi’s command for another 43 days of the Battle of the Ebro. I will get to know him well. Willi Benz: locksmith, sailor on the Kaiser’s submarine 1917-1919, in Pula, Trieste, Split, Dubrovnik and Kotor, in 1920 a fighter of the red squads in the Ruhr and a member of the KP Germany, a student of the military-political school in Moscow, etc. and now as a Battalion Commander, probably aware, certainly more aware than us ordinary soldiers, that all this that is happening in front of us, all our attacks, counterattacks, night raids (golpe de mano) in which our units melt, that all of this actually no longer has any military sense, that this war is already lost and that we are not even fighting in the present, that this is already the beginning of one of our future wars, a battle for the salvation of proletarian international nationalist honor. You have to endure in this military “nonsense”until the end. To endure in the name of that future sense that must come once again after Spain. He has to come. It seems to me that my commander Willi Benz thought so.

The last day of the battle (August 23, 1938) {sic}

In the second half of September 1938, the “Thaelman” Brigade took up positions on Sierra Caballs. No one among us even imagined that these would be the last battles and at the same time the bloodiest in the entire history of this Brigade. The Brigade was supposed to expel the enemy from Hill 565. It is, in fact, a single cut rock that dominated the entire sector of the 35th Division. Like a black eagle, the hill towered over the positions of the 11th Brigade. It rained non-stop day and night. To no avail. The Fascists on the top of the hill needed nothing else but to drop a barrage of hand grenades on the attacking fighters. Some of our men, masters in mountaineering, sometimes managed to climb up the cliffs to the very shelters of the defenders. But not a step further. The other Brigades of the 35th Division also endured unceasingly. the attack of the most elite Franco’s troops, supported by artillery and airplanes that pinned us to the ground. The entire area in the range of about 60 km turned into one general vortex of destruction in those days. Centuries-old olive groves were wiped from the ground, and vineyards were crushed by jets of shells, so on the ground sometimes human blood could not be distinguished from the juice that flowed from the black grapes that were just ripening. The density of the artillery fire from Lleria was so great in some sectors that some mounds were literally plowed over. In one of the daily reports of our Supreme Command, a sentence appeared in those days, unusual for the strict style of military communication. The sentence is exciting and difficult: “The shape of the Spanish soil is changing”. The units on one side and on the other were melting under the red-hot steel, columns of reserve units were moving towards the front, and rivers of wounded were flowing from the front. And, as if the evil fate wanted to mock, on those very days, negotiations were held in Geneva on the withdrawal of the International Brigades from Spain. My men seemed to want to defy that fate, so they waited even more cold-bloodedly to be attacked and killed. On the twenty-fourth of September 1938, the International Brigades were really withdrawn from the front, and the day before, on September 23 in the afternoon, the Battalion “12. February” was still holding its positions. But what battalion! Of the entire battalion, only the Headquarters and accompanying platoon remained, and everything else was wounded or killed. Well, nevertheless, they kept the positions until night.

During those September days, a fighter came to me every morning from the trenches to the changing room. He would sit patiently, squinting

on the ground until I finished my work with the wounded. He complained to me that he was “all sick”. Every time I would patiently examine him, but I would never find anything except general exhaustion that could easily be seen from the sunken eyes that looked hopelessly out of his bearded and dusty face. But who wasn’t he exhausted in those days? I would always end the review with a short and dry bow:

“Comrade, you’re not sick. You have to go back to the company.”

The fight against vasaka {is this a Malabar nut?}

Every morning the same procedure would be repeated.

Finally, that day, September 23, I angrily interrupted him:

“Comrade, don’t take up my time, it’s nothing to you. Anyway, tell me once, what really hurts you?”

He answered me in a contrite tone, as if he was ashamed of his actions. For these thirty years, the image of that man coming before my eyes countless times and as if begging me for mercy:

“Genosse Doktor, meine Sehle ist krank”[16].

And I always ask myself: am I correct? Was he acting, or did I make a mistake about him as a man? It probably is both are true. I have never encountered a single similar case before, not even afterwards in his war practice. I didn’t know anything about it then of acute psychoneuroses nor of “nervous breakdowns”. That terminology did not exist among us. We only admitted organic disease, and everything else was a “cowardly withdrawal from the battle”. But if I had known something more about war psychiatry, of what use could it have been in this case and in those hours that our Brigade was going through? Could I, were I allowed to act in any other way than to return this tired and mentally broken fighter to the front again? That was what the law of war demanded, the kind of war we were fighting there. I had to act as a soldier, not as a doctor, because in the war that leads to “to be or not to be”, if we have already consciously and voluntarily opted for such a war, the soldiers have the main say, and then sometimes the voice of the so-called pure “medical conscience” can be listened to. That day on Sierra Caballs, when our entire front began to shake and sway under an avalanche, there was no time or place for psychoanalysis and persuasion. Only a firm military stance was possible and justified in this case. That stance was clearly inhumane in relation to that Comrade as an individual, but it was that much more humane compared to the fighters who at that time were exposing themselves to death on the front. To recognize as an illness just one “mental breakdown” in those circumstances would mean opening wide the door for a dozen others similar to it. That is the essence of a medical decision in war.

The last morning (September 23/24, 1938)

Night fell over the battlefield, dead from mutual exhaustion. We sit in front of the shelter in quiet relaxation. I still can’t pull myself together, nor can I place myself in time and space. Everything that is here in front of me and in me, everything is still the same as it started two months ago: “Cosmic” circling of planes over the river, attacks on Gandesa (every time we say: “today must come”), floods of wounded, running under by artillery fire in a column, one by one from one wing of the front to the other, mouth parched from thirst and tension, raged at dawn, hands hardened with the blood of the wounded, Emil with half his head and – finally, that pro- cursed elevation 565 under which so many people remained.

And now, through the remnants of the Battalion, a confidential message spread: our government announced before the League of Nations the decision to withdraw all International Brigades from the front. We will be withdrawn tonight.

Is that possible? Isn’t it just a “bulo”?[17] I have neither the time nor the strength to put this news into a rational and political framework. Feelings and only feelings are holding me to these sierras and barrancos and I am not able to understand that for me, forus survivors, there is some other world and that it is given to us to step into it once more.

We came back down. We weren’t woken up by the white dawn, but by the sound of weapons. Next to us, in the direction of the front, a column was climbing, tired and drenched in sweat, the smell of which mingled with the freshness of the dawn. It’s a replacement. So what was shared with us yesterday is true.

“What unit is that, mate?”

In one single word of his answer, the fighter summed up the joy and defiance of the Spaniard:

“The Campesino!” [18]

I don’t know how that fighter, who was climbing a steep path to his position in a column, exhausted from battles, marches and a sleepless night, how he found strength and pride. I guess he discovered in my pronunciation that an International was standing in front of him.

Farewell, good friend. Hold up well. We went to the rear. I’m not allowed to tell you this, but it’s really not our fault.

Here is the pink dawn and my order:

“Muchachos, pajaros,”[19] ready to go! This rubble of bloody bandages to be cleaned. And a dead friend to bury. And nothing to clean up. Everything should remain clean behind us. Do you understand me, guys, everything needs to stay clean.

FAREWELL AND EXODUS