VLADIMIR ČOPIĆ By Vlajko Begovic

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

“The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War”

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks posted and provided links to volunteers.

VLADIMIR ČOPIĆ

By Vlajko Begovic in Spanija, Volume 5, pages 96-104

Vladimir Copić came to Spain in the first days of January 1937. At that time, the XVth International Brigade was being formed and he was appointed its political commissar. On the Jarama front, in mid-February 1937, he was appointed commander of that brigade and remained in that position until the beginning of August 1938, when he was called to the USSR. He led a brigade in the battles at Jarama, at Brunete, Zaragoza (Quinto, Belchite, Fuentes de Ebro), at Teruel in the Aragon operation, in the battle of the Ebro, etc.

The life, work and struggle of Vlado Čopić, a participant in the October Revolution, one of the most outstanding personalities of our Party from its founding until 1939, are very rich, stormy and dramatic and it is not easy to show them in a few pages.

Čopić was born in Senj in 1891 in a family of bricklayers. It’s there he finished high school, and then studied law at Zagreb University. He supported himself with scholarships, working with his father as a bricklayer, and later also in auxiliary office work. He graduated from law in 1914.

As a student, he initially belonged to the Croatian nationalist student organization “Mlada Hrvatska”. Later, he joined the progressive youth high school and student movement. When, after the dissolution of the Croatian Parliament in 1912, Slavko Cuvaj was appointed by the Austro-Hungarian government as commissioner in Croatia, there were protest meetings and demonstrations. High school and student youth take part in them and come into conflict with the police. Many young people were arrested, some were also wounded. High school students responded to this with a strike in which about 10,000 students participated. Young people twice tried to assassinate Cuvaj. Čopić is one of the organizers of these demonstrations and strikes. That is why he was imprisoned the first time and since then he has been on the list of the Austro-Hungarian police as a suspicious element. The police searched his apartment and, looking for weapons, wanted to link him to the assassination of Cuvaj.

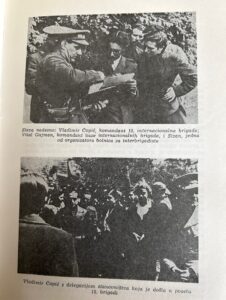

Vladimir Copic, Commander of the 15th International Brigade

At the beginning of 1915, he was mobilized into the Austro-Hungarian army and, as a suspect, was often transferred from one Hungarian regiment to another. That’s how he got to Prague, where he got to know the Czech people’s resistance to the Austro-Hungarian government. This broadens his political horizon.

In April 1916, he was sent to the Russian front as a platoon commander. There he surrenders with the whole platoon and ends up in a Russian prison camp. Until then, Copić was still a Croatian nationalist and a supporter of the radical, revolutionary struggle for the national rights of Croatia. He was also close to the idea of uniting the South Slavic peoples.

In Russia, at the end of 1915, volunteer units of Serb, Croat and Slovene prisoners began to be organized to participate in the war against the Austro-Hungarian monarchy. At the beginning of 1916, the 1st Serbian Volunteer Division was formed. The occupation of Serbia and the atrocities committed by the Austrian and German authorities on the Serbian people prompted Copić to volunteer in that Serbian division, which became part of the volunteer corps. He gets the rank of lieutenant. However, this is where he comes into conflict with the militaristic views of the officer cadre, their harsh attitudes towards soldiers, harsh punishments and the ban on political work. Copić opposed those relations. He also refused to take the oath to the Serbian king. They tried to break his resistance, threatened to shoot him, and when they failed, they returned him to the prison camp. A large number of volunteers left the volunteer corps with him.

In the camp, Copić gets to know the position of the Bolshevik Party on the war and its political orientation, which he accepts. When the October Revolution began, he stood among the prisoners for the support for the October Revolution and for the Soviet government. He organizes the fight against those prisoners who sided with the imperial government. Later he joined the Red Army and became an officer in the headquarters of the 4th Army. In the spring of 1918, he came to Moscow and joined the Bolshevik Party. Yugoslav communist prisoners organized their own group.

In the middle of 1918, he became a member of the committee of that group, then soon became the secretary, and then the president. This group of communists, together with other national groups, is linked to the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) as a section and Čopić is its representative in the Central Committee of the RKP(b). He is one of the founders and editor-in-chief of the Serbo-Croatian weekly newspaper “Revolucija”. The main work of this group of Yugoslav communists consisted in political activity among the prisoners, supporting the Soviet government, recruiting prisoners for the Red Army and preventing attempts by the embassy of the Kingdom of Serbia to recruit our prisoners for the White Army.

A group of our communists, together with communist groups of other nationalities, played a major role in political work among hundreds of thousands of prisoners, they won many over to the revolution, to the Soviet government and to fight in the Red Army.

On the twelfth of November 1918, at the conference of delegates of the Yugoslav communists, the leadership was elected, which was called the central committee. That leadership decided to go to Yugoslavia and help establish the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. They also recommended other members of the Party to return to the country.

Copić arrived in Yugoslavia together with the leadership of the Yugoslav communist group at the end of November and soon proved to be the most active and capable among them. They, like other prisoners (15,000 of them, who arrived or were arriving from Russia), were under police surveillance, persecuted and imprisoned. Copić worked on organizing the Communist Party in Croatia and already in January 1919 he was imprisoned in a military prison for a month.

At the conference of the Zagreb social democratic organization, where the left won a large majority, Čopić was elected as a delegate for the Unification Congress. At the congress, Copić was elected to the Central Council and in the Executive Party Council of the United Socialist Workers’ Party (Communists). He was working on organizing the Party to provide assistance to the Hungarian revolution. He organized a meeting in Novi Sad, in the spring of 1919, at which it was said that the Red Guard should be organized, and weapons collected, in order to protect the revolution from intervention from Yugoslavia. He establishes a council with Ivan Matuzović, the commander of the Red Guard in southern Hungary.

He was imprisoned together with a group of leaders of the Party for “destructive work in Russia and “the spread of Bolshevism in the country” and tried before a military court in May 1919. He was under investigation in Nova Ves military prison in Zagreb for almost a year. The court cannot obtain evidence. The prisoners start a hunger strike, demand a trial or release. This action of theirs is supported by young people in Zagreb with mass demonstrations. They were handed over to the civil court, which acquitted them.

Čopić is again involved in mass political work, as a prison organizer and tribune. Before the Vukovar Congress of the Party, the fight is being waged by opportunists and centrists. The Central Committee and the Political Bureau were re-elected at the congress. He becomes the organizational secretary of the KPJ. In the elections for the Constituent Assembly in 1920, he was elected as a representative of the Rijeka region. In the Assembly, he is the secretary of the Parliamentary KPJ Caucus. When the KPJ, the Communist Youth League and the revolutionary unions were banned after the »Obznana«, then the Parliamentary KPJ, protected by immunity, played a very important role.

The regime took advantage of the assassination attempt on the Regenta Aleksandra to take away the mandates of the Communist deputies and abolish their Caucus. KPJ and its leaders were accused as the organizers of assassination, and the main accused were Filip Filipović, Vladimir Čopic, and Nikola Kovačević. In court, Čopić defended the Party and its politics. In his closing speech at the court, he said: “The regime of our leaders is looking for prisons, as a sanction for its crimes against the working masses. If you pass the judgment they are asking for, we will proudly and honorably put on prison uniforms, and we will stand coldly before the courts of capitalist justice, convinced that the working people will draw new strength from our blood. To fight and die for lofty ideals is our sacred duty and we are always ready to do so.” (Borba, Zagreb 1922, No. 1 of February 19)

Since the accusation of assassination could not be proved, they were sentenced to two years each for communist propaganda. After prison, Copić is back on political work. He was elected as the secretary of the Independent Workers’ Party for Croatia and the main organizer of “Borba”. At the 2nd Conference of the illegal KPJ, the Central Committee and Poliburo were re-elected. He was a delegate of our party at the 5th Congress of the Comintern. In the middle of 1924, the regime banned the Independent Workers’ Party, Independent Trade Unions, Alliance of Workers’ Youth and “Borba”, which at the time served as a legal form of KPJ work. Copić was imprisoned on the charge of attending a congress of the Communist International. He was soon released and organized the publication of “Borba” under the name “Radnicka Borba {Labour Struggle}”.

In mid-December 1924, he was imprisoned again and accused of his activities as regional secretary of the Independent Workers’ Party and editor-in-chief of “Borba”. In the minutes of his hearing with the police, he says: “As the regional secretary of the Independent Workers’ Party, I extended my work despite the ban from July 11, because that ban was in conflict with the Constitution and existing laws. We do not consider that ban as an illegal act and we will not recognize it. The working class has the right, within the limits of the law, to all political and civil liberties, just like the other classes, and this right cannot be taken away from them by any unlawful and violent acts” (Labor Struggle 1925, No. 17 of May 7).

The state prosecutor asked for the death penalty or twenty years in prison for Copić. The process caused great interest in the public. Copić defended himself in court, accusing the regime of violence and crimes committed against the working class. There was no evidence for conviction, but he was sentenced to three and a half years in prison. However, Copić escaped after a few months and went to the USSR. In Moscow, he studied at the International Lenin School for three years, together with Duro Daković and Blagoje Parović.

At the beginning of 1930, the Comintern sent him to Prague to work as its instructor at the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, where he successfully performed this function for two years. At the beginning of 1932, the Czech police discovered him, imprisoned him and exiled him to Germany, from where he went to Moscow. For a short time he worked in the Comintern. He soon left for Vienna to take up the position of organizational secretary and member of the Politburo of the KPJ.

In 1934 he returned to Moscow, there as a representative of the KPJ and the Comintern. At that time, he developed great political activity with our cadres who came there for education or to live in the USSR. At the Fourth Land Conference, he was re-elected to the Central Committee of the KPJ, and in 1935 he was a delegate of the KPJ at the VII Congress of the Comintern. At the end of the same year, he went to Vienna, where he works as a member of the Politburo of the KPJ Central Committee. In 1936, he worked illegally in the country. That year, he came into conflict with the general secretary of the KPJ, Milan Gorkić, and in the fight within the Central Committee at that time, he was expelled from the Central Committee of the KPJ as a “left factionist”. He went to work again in the KPJ of Czechoslovakia, from where he arrived in Spain at the beginning of January 1937.

I met Copić for the first time in Prague in 1931. He was in the company of a leader from the Central Committee of the KPC and his name was Gregor. I didn’t know he was from Yugoslavia. I was surprised by his great interest in Yugoslavia and also celebrated the fact that, speaking Czech, he pronounced the names of our cities and people well. Then and later when we met, we only spoke Czech. I suspected that he was not Czech and believed that he was of some other Slavic nationality and that he had lived in Yugoslavia for a long time. I liked him and his interest in Yugoslavia and I was glad when I could meet him. Disappeared. I heard he was locked up. Comrade Marjan Krajačić came out of the police prison at that time and told me that he met a Yugoslav Copić there. He described him to me, and according to the description, it could only be him, Gregor. We knew about Vladimír Copić and his role in the KPJ, we remembered his character from photographs from 1920 with a distinctive black beard and moustache. We didn’t believe that it was Copić.

Later in the fall of 1932, leaving Prague to work illegally in the country, I stopped by Vienna, where the Central Committee of the KPJ was then. Copić was the new organizational secretary under the name “Vinter”. I also met him in Vienna in 1933. When I came to Moscow in February, our representative in the Comintern, “Senjko”, was Copić again. Sonja Fijalova, whom I knew from Prague as the chief of staff of KPC organizational secretary Rudolf Slanski, was his wife. They had a son Zoran.

In 1937, I was together with him again in Spain. We worked in a group whose task was to help organize the XVth Brigade. I spent most of the war in Spain with him in the XVth International Brigade or was in contact with him working in the headquarters of the Interbrigade base and in the headquarters of the 35th division, which included the XVth brigade.

Working with Copić before Spain and in Spain was pleasant, working with him had a certain concrete content and was organized. He brought his experience in working with people to Spain. He was happy to go among the fighters and trenches and talk with them, sometimes singing. He had a musical education and a beautiful voice. In addition to folk and revolutionary songs, especially Russian ones, he also sang arias from operas. At the time of the October Revolution, when the Yugoslav group found themselves in difficulty without money, they organized concerts and Copić would sing. He also performed at events of Comintern associates in Moscow. He became legal in Spain and often told us about the events of his revolutionary work in Russia and Yugoslavia. He always remained measured in his relations with colleagues, never familiar.

From all those meetings and cooperation, Copić remained in my memory as a capable man, a good organizer, experienced and calm, who knew how to keep his cool and be brave in the most difficult situations. He systematically and meticulously studied what needed to be carried out, and in carrying out the tasks he was persistent, and sometimes so a little stiff. He was not a man with the pretensions of a theoretician, nor did he engage in abstract considerations. He organized and acted systematically within the set framework.

During the operations, his headquarters is always close to the front, near the front covered by his brigade, he is often surrounded by olive trees, in a hole by the side of the road, in a dugout, in a ravine, in a trench protected by sandbags, and sometimes in abandoned houses. Sitting with the maps on his lap, he reads the received orders and prepares his own, picks up the phone and conducts short conversations, talks with the battalion commanders, listens to the reports of the liaison officer, and then stays for a long time at the observation post of the brigade headquarters. He is persistent in his efforts to find out the real situation on the front line and the effectiveness of individual units, he follows every stage of the implementation of orders. When there is a break in the battle, he holds meetings with commanders and commissars. If necessary, he does not sleep for several nights.

In the beginning, it was not difficult for Čopić, as the commissar of the brigade, to fulfill his role, but he lasted very little time in that role. He became a Brigade Commander in very difficult conditions during the battles at Jarama, the biggest battle in Spain until then. With his persistence, organizational ability and cooperation with the Brigade staff, he overcame all difficulties and became one of the capable and favorite commanders of international brigades.

All the time he was in the XVth brigade, where the “Dimitrov” battalion, which also included our fighters, was in the beginning. He developed very nice relations with them. Later, when the French-Belgian battalion and the “Dimitrov” battalion left the XVth brigade, the Brigade became American-Canadian-English. Čopić remained as brigade commander, learned English well and was very well received in the brigade.

When he came to Spain, he still bore fresh scars from the internal struggle in the KPJ Central Committee. He did not want to talk about those relations, except for scathing remarks, especially against Gorkić. He was bitter and avoided any connection with the leadership of our party at that time, including many cadres who came to Spain. The KPJ leadership at the time was afraid that he would be active among our people creating opposition to the leadership. However, Čopić isolated himself from the management, and initially from a good part of our staff in Spain. Later, he developed more and more ties with our people in Spain, especially with the fighters.

The connection with the fighters, the war and the Spanish problems distanced him from the old disagreements, and he began to reason more calmly about everything. On the other hand, the Central Committee tried to bridge the created gap. Parović, appreciating Čopić and his role in the Party and Spain, worked to smooth out the old conflict. Čopić’s editorial was published in the organ of our fighters “Dimitrovac”, his own photos and writings appeared in which he is spoken of with respect. Then “Proleter” wrote about him as a prominent military leader in Spain and published his picture. This brought him closer to our party leadership.

At the end of August 1938, he was informed by the Comintern that he should go to Moscow to join the leadership of the KPJ. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Spain, while organizing his departure, accommodated him in Barcelona in a villa. Everyone treated him as a future leader. And he behaved like that: he consulted about future work and personnel and prepared for upcoming party work. However, when he came to Moscow, he did not even see his family, but was imprisoned, convicted and shot as an “enemy”. Later, in June 1958, the Supreme Court of the USSR established that the charges against Čopić were unfounded and he rehabilitated him as innocent.

Vlajko BEGOVIC {aka Stefanovic}