FORTRESS COLLIOURE By Svetsilav Dorevic

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

“The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War”

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks posted and provided links to volunteers.

FORTRESS COLLIOURE

Svetsilav Dorevic, Spanija, Volume 4, pp. 116-152

The end of our fight has come, the last engagement of the Internationals was to help the Spanish comrades to keep the enemy at least a little bit, so that the evacuation of what had to be done without panic and in order could be carried out, so that it would not fall prey to the enemy, as well as to avoid capture of people who were in mortal danger.

The enemy was staring.

In the last days, they mercilessly bombed and destroyed the city of Figueres — a wonderful border town — needlessly. Probably more out of hanging and revenge…

We were ready for evacuation. Several of us patients were placed in ambulances and early in the morning, February 8, they were sent from Llers to the French border.

Due to the effort I made during the last days of the war, my legs were very swollen, and my feet hurt so much that I could hardly stand on my feet. And my heart gave way, I also had a rather high temperature. In the car, next to me, there are some other patients including engineer Dragutin Gustinčić, Aca Mirić, Franjo Serafin and some other comrades.

In the beginning, we moved without holding back. But, we were getting closer to the French border, the column was gradually slowing down, and it started to stop. The danger from aviation is great, because there is nowhere to hide. Everything is clean, like in the palm of your hand. The road winds uphill full of trucks, cars and pedestrians, loaded with various things, which people hastily picked up and took with them.

No one knew the exact cause of the slow motion, but everyone guessed the reason. The French accepted refugees in their own way. They were in no hurry. They were not in any danger. Well, nevertheless, we are slowly approaching the border. It is already afternoon, the sun tends to fall. We can see the border crossing as well army and police. The soldiers are black Senegalese, and there are also Guardmobile Police, famous for their brutality.

Weapons of disarmed Internationals

The order comes for us all to get out of the hospital car and cross the border on foot. They conduct a search but superficially. They mostly take away weapons.

Gustinčić is in front of me. The Gardmobiles take his revolver and let him go, laughing with satisfaction that they have disarmed another Spanish officer.

Seeing this I returned back to Spanish territory. Across, I took my Browning, emptied it and scattered the ammunition everywhere on the sides. With the Browning, I chipped the stone until it had taken enough damage and then threw it far into the field.

The police officers shout something and get angry. I guess it’s their fault that I didn’t hand them the revolver.

We thought they were going to load us back into the ambulance. We were mistaken before. They sent the car on the road, empty, and left us to go down to the Cerbere Station on our own. They transported only the literally immobile wounded and sick.

It was a terrible picture: thousands of people, women, old people, children, overloaded with various things, they moved downhill, down the Pyrenees Mountains, on a roadless track through a fairly dense forest.

The most loaded women are women who, in addition to belongings, also carry children in their arms. The downhill is long and the terrain is slippery. There is no way. Children fall and cry. Mothers too. We help them, as much as we can, to go down the hill with the children.

At the bottom of the mountain, a wide meadow. Meadows. The weather is nice. Warm. The sun is setting. We are at the railway station Cerbere. But there is one more barrier to overcome. The gendarmerie is stationed in front of the stands. And they conduct a search. They are taking away “cold weapons.”

They searched me and found an ordinary small penknife with two small blades. The gendarme takes it from me and puts it in his pocket. I was already too irritated from fatigue and fleas, so at the end of nervous exhaustion.

I asked for the penknife back, and the gendarme just smiled sadly and gave me a hand signal to go on. I pointed with my hand that he was a thief, using the Spanish word “ladron” This seemed to offend him, so he started shouting and pushing me. This exhausted my patience. Like a madman, I grabbed his chest and started shaking him. This confused him. He took out the penknife and handed it back to me.

At that moment, Gustinčic shouted: “Are you crazy?” What are you doing? Let him go!” But everything was already over, so we moved on.

They brought us to the Cerbere station and placed us under the covered platforms for unloading goods. Apart from a roof over our heads and straw mattresses with straw for lying on the platforms, we didn’t get anything else. This is how the reception point for the wounded and sick was arranged. The others could sit around in the field, wherever they wanted.

I was completely exhausted, fainting, so I immediately lay down. Gustinčić called the doctor, who helped me by bringing me drops and some pills a few minutes later.

I lost myself again in unconsciousness and deep sleep. The night was cool, and we were lying without a blanket. The cold woke me up. It was easier for me, but my temperature was still quite high. When they measured it in the morning, it was over 38 degrees.

After the examination and careful selection of the patients, they attached some printed cards to our lapels, as a pass to enter the train, which was already set up at the station. The others, even those wounded in the head or another part of the body, only if their legs are intact, they had to walk to the Argeles Camp.

They took us by train to Argeles and disembarked at the station. Then the funeral attendants directed us to the camp, which was located at the end of the city, on the very seashore.

Argeles is a small town that at that time had barely two thousand inhabitants. It is beautiful and attractive and was probably full of tourists during the summer, because it has a very spacious and wonderful sandy beach.

As we passed through it, barely dragging our feet, the residents looked at us with pity, and some even greeted us.

Finally, we passed the town and approached the beach. We came across a gate made of barbed wire and saw that the entire area extending for several kilometers was surrounded by wire. Towers were also built for the observation of the Camp. Behind the entrance was a building that housed the Camp’s Administration. Next to it, some barracks were erected, probably for the needs of the Police and the Administration. Farther into the distance, bare sand stretched to the left and right. And in front, and slightly to the right, at 300-400 m, you can see the coast with the beautiful blue Mediterranean Sea.

As soon as we passed the gate, we were completely “free.” We could choose a place on the beach to our heart’s content. There were already tens of thousands of people, women and children, of various nationalities. New ones kept arriving.

And the accommodation is the same for everyone: sand, on a long and wide coast. The month of February, and no sign of yesterday’s sun. It is quite fresh. Even a light breeze blows, and we are in an open area, on bare sand.

No matter what, people manage. They are grouped by national, regional or military affiliation. We encountered our Yugoslavs who came before us and settled next to them.

There is no food and no water to drink. There is also no sanitary devices. What will happen with this many people?

The night is approaching. You should get ready for bed. I still have a fever. Some friends brought me some aspirin tablets. Others procured and gave me two blankets. We divided into groups of 4-5, spread two blankets over the sand, and covered ourselves with the rest. That’s how we met and spent the first night in the Argeles sur Mer Camp.

Miraculously, I slept unusually well, I didn’t even feel the cold. In the morning, we went to the shore and washed ourselves with fresh sea water. My temperature has dropped a bit, but my legs are still swollen, especially the soles. That’s why I was forced to sit down.

The beach is getting more and more crowded. The alarm is getting bigger. Like at the fair. People are hungry and thirsty. It’s worst for children. Gendarmes begin to bring bread on trucks. They give it out without any organization. Water tankers are also arriving. Whoever is stronger takes two loaves of bread each, and supplies himself with water faster. The others will wait until the second tour arrives. There is no organization that would make the distribution.

Guardmobiles are everywhere. They observe that we are tired and it seems that they are satisfied watching how starving people grab each other for bread and water.

Canopies on the sand in Argeles

The first days pass in such chaos that it is difficult to even describe it. And then the Party steps into action and tries to organize life. The grouping by nationalities begins. Spaniards are grouped mainly by Brigades, and also by places of origin. We were among the first to organize our group of Yugoslavs.

After the intervention of the Camp Authorities, supplies began to be made by groups. A few days later they also gave us military kitchens with the necessary accessories. Soon we start to raise the roof over our heads. In fact, they were mostly canopies, raised on a few sticks and covered with a tent wing or some other textile item. Many found their tent wings, and some were also found in quartermaster trucks. Apart from that, we constantly made requests to the Camp Administration and asked for tents or barracks. Soon we received the material for the construction of a prefabricated shed for the kitchen. Our friends quickly assembled it. In a few days, each group of several hundred people received its own prefabricated kitchen.

Life is normalizing, we get food fairly regularly, and in sufficient quantity.

The camp is already full. There are maybe over a hundred of us. Boiling like an anthill.

After a few days, my friends found our truck with things. We received our suitcases, backpacks, or bags that we handed over when leaving Llers. That’s good, among these things people had something that was necessary for their life.

Now I feel good too. The temperature has completely dropped, and the swelling on the legs has decreased. Even in the worst conditions, the organism fights for survival. We satisfied our hunger. We even have tobacco, and we also acquired stationery. We are contacting our relatives to know where we are and how we are.

In the tent buried in the sand, next to me, there were other comrades: Fadil Jahić, Aca Mirić, Pera Stokić and Bogdan Milošević . In the Camp, regardless of the harshness of the living conditions, a pleasant atmosphere was established. We loved a joke, so they would create a cheerful mood in no time. Most often, such an atmosphere was created by the always cheerful Bogdan Milošević, whom we also called “Pilićar”. That’s why I especially liked him.

I met Bogdan in Catalonia, on the day when the “Divisionario ” Battalion was formed. We met quite by chance. He was accompanied by a Soviet adviser whom he also served as an interpreter. I immediately noticed that he was a very poor interpreter. Instead of Spanish, he used French, and instead of Russian, Serbian. I proposed Isa Baruha from Sarajevo as an interpreter to the Soviet adviser. He accepted it, but it was difficult for him to part with Bogdan, whom he praised as a good friend and a very resourceful and brave companion. However, happy to meet the Yugoslavs, Bogdan gladly accepted the exchange, just to join us as soon as possible. He immediately told us everything about himself. He is from the village of Ripnja near Belgrade. He left Zemlja ten years ago and went to France to look for a job. Soon he encountered agents recruiting for the party legion. He did not know the life of a legionnaire and it was not difficult for a skilled agent to put him on thin ice. He signed a contract for five years and served as a legionnaire in Algeria, Madagascar and Indochina. At the end of his duty, he returned to France and got a job as a laborer, and in 1937 he came to Spain.

He was a fighter in the Spanish units, until he became an interpreter. As the “Divisionario” Battalion was being formed that day, and the supply had not yet been organized, I was without food and hungry. Bogdan noticed this, so he suggested to us (me, Mirko Marković, Bora Pockov, Cedi Kapor, Peko Dapčevié and others from the group around him) that he get food. We collected and gave him a lot of money and he left immediately. Since a lot of time has passed since Bogdan’s departure, our friends started laughing and teasing us for our naivety. However, when we already believed that we were deceived, Bogdan appeared with a heavy load on him. He brought two chickens, some bacon meat, bread, many almonds and a flask of wine. We all rejoiced together, although we felt ashamed because of the mistrust shown towards the other. Soon a good dinner was prepared for the whole group. We praised Bogdan, but jokingly gave him the nickname “Pilicar ” by which many people will recognize him in the future. Bogdan stayed with us in the unit until the end of the war and his resourcefulness was always useful to us.

Even here in the changed camp conditions of life Bogdan took on a delicate job. He supplied our group with food. How and from where he procured it, we never found out. The assumption I believe he had close ties with the person responsible for the supply. However, one detail was the most interesting. One day Bogdan brought 25 kg of sugar and about 40 kg of flour to our tent and accompanied them with the words: “There was no need for evil”! We all rejoiced, and Fadil to him jokingly said:

“Eh, my friend, if you had brought more oil, I would have made such halva that you would eat your fingers with it.”

Bogdan promises to get that too. He disappeared during the night and only returned before dawn with a bucket of oil. We were already awake and praised him. He laid down in my place and immediately fell asleep.

When we were sure that Bogdan was sleeping soundly, we got up. Fadil suggested that we joke with him and check if he would be able to get the oil in the middle of the day. We took the oil to the kitchen, served it, and poured water into the bucket and put it in the place where he left it.

When Bogdan woke up, Fadil and Pera Stokić “attacked” him for tricking us into bringing us water instead of oil. Understandably, he was surprised and swore to everyone that he had brought real oil. When he made sure that there was water in the bucket he became sad and made an excuse, saying that someone must have stolen the oil or replaced the bucket while we were sleeping. We insisted that it was impossible, because we were no longer asleep, and we opened the bucket and found that there was water in it as soon as he fell asleep. We told him that his “action” surprised us, but that we didn’t want to discuss it until he got some sleep. However, even though he pretended to believe us, he was still convinced that we had fallen asleep again and that someone had stolen our oil, so he said somewhat offended:

“Well, now I will bring you oil from the same barrel in the middle of the day, no matter what happened to me.”

He fulfilled his promise. After two hours, he brought another can of oil. During that time, Fadil made halva in the kitchen and distributed it to everyone. One portion was also left for Bogdan.

When the halva was given to him and we all started laughing, he realized yes we fooled him and that the prank was successful. At first he was confused and angry, and then he started laughing and joking himself. We were also in a good mood because we now have another can of oil in reserve, and our favorite thing was that we made sure that Bogdan was capable of performing such a feat, which was very risky in the camp conditions, even in the middle of the day. However, Bogdan never revealed to us the secret of how he procures it.

Various voices are heard among the soldiers and the refugees. The enemy does not sit idly by. Spaniards are invited to return to Spain. Propaganda is carried out among the Internationals with the aim of demoralization. The same thing happens with the Spaniards. Recruitment for the Foreign Legion begins. It seems to be quite a lucrative business for recruiting agents.

That needs to get in the way. We approach the organization of party cells. We connect with each other by nationalities and create an organization of Internationals. We also organized a Camp Committee. The Committee is headed by Comrade Otto Flatter-Dr. Ferenc Minih, Hungarian, who lived in the Soviet Union for a long time and was in the 9th Brigade.

We organize systematic work. We give reports on our situation and perspectives, we give organized information from the press and instructions on how to suppress enemy propaganda in order to preserve the morale of the Spanish comrades and among the Internationals.

From our group, a group stood out, so-called anarchists. There are similar ones among other nations. They impose themselves as the leadership in the Camp. Most of them are dissatisfied for any reason, mostly personal. Among them there are also enemy agents, previously inserted into Spain, who have become active and are openly working against us, the Communists, at the same time blaming us as the “culprits” for the defeat and all other troubles.

The best Communists of our group, in cooperation with the Communists of other national groups, were the initiators of the struggle for the right to asylum, better accommodation and food in the camp, as well as for a dignified but also decisive attitude towards the French Command in the camp. Namely, the Command did everything to disunite us. Among other things, they tried to impose on us the treatment of a prisoner who was captured by the self-appointed management of the Camp, among whom were some of our Yugoslavs. Standing up against such an opportunistic, unworthy attitude, we asked André Marty, through our connection (a nurse), to remove the self-appointed management and appoint another. Marty agreed with that and sent a written message in that spirit. After that, the situation among the Internationals changed significantly and our political work revived.

There are representatives from the League of Nations who do the registration of refugees. From the Yugoslav embassy, he also comes before our representatives and promises return to the country, but on the condition that he repents.

Our organization is working at full steam. We keep people together. We are unique. We are also starting to issue wall newspapers. I was in charge of arranging them, and there were many collaborators. In addition to articles about life in the camp, there were also some illustrations and even caricatures. It was a real joy for all our people when they saw and read those wall newspapers.

But the French police did not sit idly by either. They were, it seems, well informed about everything that is done here. And under these conditions, it is not difficult to find a traitor and a denouncer. They started calling us and entering information in a special form. This was the basis for them to create special personal files for each of us. Over time, these files were quite well completed. I received my file, after the liberation of France 1944, and brought it with me, as a rare souvenir.

Time is running fast. It was already March 14, 1939.

That day, in the evening, a large group of armed guardmobiles arrived, with one large “maricom”. They came to our part of the camp and read the list of 14 comrades, namely:

Abramović Josip Ludek, Dapčevic Petar Peko, Dorđević Svetislav, Kalafatić Milan, Kurt Vladimir — Maier, Jahić Fadil, Jazbinšek Viktor, Rainer, Juranić Oskar, Mirić Aca – Kabanjero , Mitrov Slobodan, Popović Vladimir, Serafin Franjo, Stanisavljević Dimitrije – Furman and Stokić Petar.

After they called us, they ordered us to collect our things and come immediately. None of us tried to hide or avoid arrest. After all, we didn’t even know what they were thinking of doing with us.

It was already night when we were ready and together. When guardmobiles, with guns ready, chased us out of the camp, ours International Comrades and Spaniards, as a sign of solidarity and protest, followed us all the way to the Camp wires, seeing us off with raised fists. Then they loaded us into the “Paddy Wagon” and left from the camp towards Argeles.

From Argeles, the road to the right leads in the direction of Perpignan and beyond, and to the left – in the direction of the Spanish border.

We thought that they would transfer us to another Camp or prison in order to isolate us from other Yugoslav fighters. The police were well informed about who we were and what we were doing in the camp, so we assumed that they wanted to get rid of us. Looks like we were right.

We reached Argeles and the “Paddy Wagon” turned left. We know that leads us in the direction of the Spanish border. Nervousness increases. But I guess we should be taken away and handed over to Franco! Anything can happen, the French government, headed by Mr. Daladier, was not a bit in our favor. Even, on the contrary. Franco became closer to them and they did everything they could for him. We talk and think about what awaits us.

Fortunately, this uncertainty did not last long. We soon arrived in a small town, passed through a small square and entered a large fortress.

It was the Collioure fortress.

It is located in the town of the same name and named after it, “Fort Collioure”.

They disembarked us and took us to the courtyard of the fortress. dead silence. And complete darkness. They lined us up in the yard with things and left a guard to watch over us and not allow us to talk.

To the right of the entrance to the courtyard, almost at the bottom of it, was a large office with a fairly large window. Soon the Lieutenant – Adjutant of the Commander of the Fortress-prison, a second Lieutenant, a Sergeant called Brka, a Sergeant “Kvadratna glava” (square cabbage) and two more guardmobiles arrived there.

I don’t remember who was first. But as soon as he entered, he was greeted with slaps. We observed all this from the outside. I guess they wanted to create the right impression, in order to confuse us so that later, when searching and confiscating things of value, it wouldn’t even occur to us to complain or protest. Neither the second, nor the third, nor the fourth comrade Milan Kalafatić fared any better.

All that procedure was very humiliating and caused a terrible revolt among us. Seeing how the previous Comrades fared, I decided to resist them, but I couldn’t hope for the best. I understood, they wanted to scare us and let us know that we can’t behave with them like in the Camp.

It was my turn. I took my suitcase and purse and entered the office. I hadn’t even managed to put my things down to take off my hat, and Sergeant Brka waved his hand and knocked it off me, yelling, I guess, that I was coming in with a hat on my head.

That was enough for me to fire away at him in pure Serbian language at “p.m.”{probably Pička Ti Materina – your mother’s vagina}, throwing the suitcase and purse on the floor, ready to confront me physically. However, to my great surprise, and that of the others, Brka burst out laughing with the comment: “Ooh la la — Serbo – p.m.”

Everyone was amazed and asked “Brka” what I said. In the meantime, while Brka was explaining, a gendarme handed me a hat. Of course, I didn’t understand everything, but by the expression on his face and from what he was telling them, he understood that he had already learned these words from the Serbs on the Thessaloniki front and that they were an expression not only of our dissatisfaction, but also of good mood. Everything depends on the circumstances in which they are said.

Finally, the Lieutenant warned Brka not to exaggerate in his actions towards us, so there were no scoldings and rough treatment of the next comrades. At last, we all calmed down.

The search began. They looked through everything in the suitcase and wrote it down, mostly larger things. In my suitcase, I had, among other things, a box in which there were buttons made of Toledo gold for a shirt, a pin and a tie clip. It’s not that expensive valuable objects, but they were important to me, because I for them got the memory from a friend from Canada, after the Brunete operations. The gendarme liked it and, so that others wouldn’t see, he put the box in his pocket.

I noticed that and demanded in Spanish that he return the box. At the same time, I used the word “ladron” and showed with my hand what pickpockets do when they steal. Since they live in the border zone with Spain, they know the Spanish language quite well and everyone understood me, so the Lieutenant, followed by Brka and the others, shouted to the Gendarme and ordered him to give me back what he took. The Gendarme bowed his head and returned the box. But at my insistence that they also put it in the list of things, they waved their hands and told me not to be afraid that it will disappear.

In fact, they were lying. Later, when I was taken out of prison and taken to the hospital, the box was not in the suitcase. They stole it, along with some other things. When I asked them where these things were, they told me that everything on the list was there. And I can’t ask for that it is not even recorded.

What can be done there?

The procedure surrounding the search, confiscation of personal belongings and entering them into the prison book took quite a long time. During that time, we were forced to stand in the yard. We still weren’t allowed to talk to each other. I guess so as not to “disturb” the other inhabitants of the Fortress.

After the search was over, they took us upstairs, in the same wing of the building, and locked us in a larger room. There was no lighting. The floor is made of ceramic tiles. It used to be a palace building of the Aragonese rulers. In its time, these were probably beautiful rooms. The windows are single-hung, but still well preserved. After all, they don’t practice double windows here, because the climate is quite mild.

We sat on the floor, some even lay down. We talk about where we are and what they intend to do with us. No one told us why we were brought and whether we would stay there. Maybe we will just spend the night. Nervousness is therefore quite understandable. In such circumstances, the secretion of urine increases. There are fourteen of us, but they didn’t give us any place to know how to go. One friend who knew French, opened the window and asked the guard for guidance. The gendarme just shouted at him and ordered him to close the window.

What to do? It was impossible to urinate in the room. We couldn’t even sit on the floor without getting wet. Nevertheless, a way out was found. Franjo Serafin had rubber boots. He took them off and after we had done the work in one, we spilled the urine through the window into the yard. The guard reacted furiously, cursing and threatening. But that was the end of it. When we did that later, the guard’s reaction was much weaker. Who knows, maybe it was another guard?

The main thing is that we were able to rest lying on the dry floor, even though it was quite cold. We even overslept a little. Those who had weaker nerves did not even flinch.

In the morning, they took us out of the room and formed us as a special section. There were over 100 Spaniards in prison, most of them Communists, some Internationals, who were forced to do forced labor. (After three or four days, they separated us and put us among the Spaniards, two each in a section).

We received cutlery: tin military portions and spoons. We washed up and had breakfast. For breakfast, there was quite a good spread of soldier’s bread. It was even greasy.

From the Spanish comrades with whom we were together, we soon found out where we were, what the regime was like and what was being done. Everything was clear to us.

This was a real prison with forced labor. Maybe even with useless, but necessarily hard physical labor and constant beatings. We agreed to sabotage that work as much as possible. We informed our Spanish Comrades about this and they accepted our suggestions.

Prisoners are divided into sections of 18-25 people, which depends on the room where the sections are located. Two sections are located in large spaces. Each section had its own boss. It was a member of the Guardmobile. He took care of the section, carried out roll call, control, took mail for sending and handed over incoming mail, controlled the order in the rooms, took us out to work with the assistance of armed soldiers.

These soldiers were black Senegalese. Their officers prepared them well to be as cruel as possible to us. They lashed out at us, without any reason for it. One would say real savages! No wonder. They were informed that we were Communists, godless and real bandits, who were slaughtering all over Spain women, children, old people, burned down churches, tortured and killed priests, etc. Such people cannot be treated differently, only cruelly and without mercy. And they, in most cases, acted in the same way. At least in the beginning.

But nothing is eternal. And lies have “short legs”. Some of our Comrades who knew French managed to explain to some of them that what their Officers told them was not true, but that we were fighters against fascism and imperialism, that we were fighting for the freedom of the Spanish people, for the freedom of the oppressed and oppressed.

And that quickly spread among them. Their cruelty is reduced and sometimes turned into friendship. It was later that some of us were also given cigarettes. The Officers noticed and started to punish them. They simply beat them like cattle. But that didn’t help much. Finally, they replaced them. In place of Senegalese, French soldiers were brought in. They are also in charge of us in the same way as the Senegalese. But the French did not believe, because they read the press and already knew everything about us. Besides, there were Communists with them, who sympathized with us and often helped us. Therefore, it was much easier for us with them. But prison is prison.

A few days after arriving, we agreed to collectively ask the prison Commander for an explanation about our arrest. If we are guilty, let them file an indictment and bring us to court. If we are not guilty — and we claim that we have done nothing against the law, then let them return us to the Camp from which they brought us. Otherwise, we will not go to work and announce a hunger strike.

Before starting this action, through a fellow Spanish truck driver, we sent a letter to the Committee for Aid to Spanish Fighters in Paris. In that letter, we informed them in detail about the regime in the Collioure fortress and that we would go on a hunger strike. We also informed the Spanish Comrades in Collioure about our action. The Spaniards agreed with us, but they could not start a joint action. However, this action greatly contributed to raising morale among the Spaniards, and especially to the influence of the Communists among them.

There were several comrades among us who knew some French, the most prominent being Oskar Juranić, a lawyer from Rijeka. He was given the task of formulating our demands in writing in French, which, later, together with Vlad Popović, on behalf of the whole group, he would submit and present orally to the prison Commander.

The request was formulated on the morning of March 21, so the two of them, through their boss, reported to the Prison Commander. I no longer remember how the commander received them and told them everything. In summary, from their conversation I know that he was unusually angry, almost to the point of rage. For him it was lightning out of the blue.

The commandant of the prison was a well-known legionnaire captain, Mr. Rollet. He is the son of the old legionnaire General Rollet {Dordevic says Role}. A tall and well-built officer, rough and strict to the point of brutality, who often aspires to worldly sophistication, quite educated. He knew the German language well. His face was pimply, it was easily quite red even in his forties, as is the case with a large number of people his age, who enjoy a large amount of wine. He was also loyal to his subordinate guardsmen. They feared the squad, nobody liked him. Later, I noticed that he had left the habit from the Legion, of not giving peace to anyone. He forced everyone to train, especially on motorcycles with a trailer. He was a real master and acrobat in driving a motorcycle with a trailer. He demanded from the Guardmobiles that, like him, the motorcycle was driven on two wheels, and the trailer had three wheels. This was not easy to do because the trailer was loaded with one of the Guardmobiles. In addition, he constantly demanded from them that the prisoners be treated more harshly.

When he read our request, he got angry. They gathered us up. It wasn’t even difficult, because we were all already together because we refused to get in the car and go to work.

They lined us up in the yard. Captain Rollet approached the formation and touched each one of us on the cheek, asked:

“You don’t want to work?”

Of course, the answer was negative.

“Well, we’ll see who is stronger, who will last longer!”

The Commander left the guards next to us, and he and his associates, angry as a beast, went to his office, probably to agree on the further course of action towards us, and also to inform their superiors about it.

After some time, we noticed gendarmes running around the Fortress. A little later, the isolation operation began. They divided us into three groups. There were only two in the first group: Oskar Juranic and Vlada Popovic. They are the submitters of our ultimatum, so they are qualified as “group leaders”. The other two groups each had six each.

The first two were placed in a cell, which was located in the inner wall of the fortress. It is a small room without windows. Suitable for leaving some old things, which are not for use, it was by no means suitable for human life.

They put the second group in a real prison cell designed for 2-3 prisoners. Maybe four at most.

It also had good “dusema” {corrupted French} (beds made of boards) for sitting and lying down, a window with a grill and a door with a peephole.

They placed the third group in a large “hall”, which is in it was probably beautiful in its time and who knows what purposes it served in the former castle. But now it was just an empty room, about 50 m in size, over 3 m high, from whose walls and ceiling the plaster had long ago fallen and covered the entire floor surface. The only large window, facing the sea, had already been broken a long time ago. That hall was in the immediate vicinity of the large outer wall of the fortress, built on the rocks of the sea coast. The sea itself is no more than 20 meters away, but the height of the window above the sea was much higher. Our guards gave us a completely free hand to “freely” jump from the window if we wanted to commit suicide. It only depended on our personal mood.

Before being placed in these rooms, there was also the usual strict personal search and confiscation of writing utensils, shaving and the like. They went so far as to strip us completely naked and even, individually, peer into our buttocks and order us to cough.

When they accommodated us so “nicely”, they informed us that according to the Commandant’s order, since we don’t want to work or eat, we won’t even get water. And if someone wants to eat, let them know and we will get a meal and water.

And what can be done there? An order is an order. But our decision was also firm. Persevere until victory or death.

It is interesting that the Gendarmes could not even imagine people going on hunger strike. They understand when people strike by stopping work, but it never occurs to them to go on a hunger strike. In total, they shook their heads and said that we are just crazy and that hunger will soon make us wiser.

They visited us occasionally, two to three times a day, to see how we were doing. On that occasion, they beat someone or threatened to beat them, but that was always the end of the matter. It seems, however, that they were ordered not to beat us. Otherwise, if it wasn’t for that, they probably would have had a very bad time, because almost everyone in the Guardmobiles were unusually revolted by our insolence.

Immediately after receiving our letter, in Paris, as well as in the whole of France, a broad campaign against the “Collioure system” developed. The actions of the military and police authorities against the Spaniards and Internationals in the French camps and prisons were also contested in the French parliament. The names of some of our friends were sent letters of support with hundreds and thousands of signatures, then packages with food, cigarettes, etc.

We ourselves, only found that out after the strike was successfully completed, that is, after returning to the Argeles Camp.

After two days, they exchanged rooms. We from the “Salon” were transferred to a prison cell, and those from the cell to ours. On that occasion, too, there were no shortages of minor taunts and big threats and curses. Gendarmes work.

We were completely calm and determined. We are certainly hungry – the feelings are unequal, some suffer more because of hunger, while others find it easier to bear. However, it was much more difficult when we were without cigarettes, the bowels were cramping, but all this could somehow be tolerated. We asked the Gendarmes to bring us some, and threatened to answer if anything happened to us because of the tobacco, but it was all in vain.

“Those who don’t eat don’t even need to drink” – they would say.

However, at the end of the third day of the strike, they brought us a full bucket of water and a large cement can. I couldn’t wait for my turn. I drank a full cement on the excavation, and later I was still drinking {translation does not make sense}.

That was our first victory.

The Commander and his superiors had to capitulate. They knew that after three days of thirst, various complications can occur, dangerous for our lives. And, they were not allowed to take risks, probably because of a possible international scandal.

We found out later that the French public found out about our strike. While we were well isolated from the rest of the world and knew nothing of what was happening outside, there was quite a stir in the press. His superiors visited the Commander and gave him instructions on what to do and how to deal with us.

On the fifth day, the Commander ordered us to be brought to the front of the infirmary, which was located on the first floor, in the left wing of the building. They brought us in groups, as we were isolated. My group was the last. We entered the infirmary one by one, including the Commander tried to convince us, in a fairly calm conversation, to let me know we are not in a prison, that it is an ordinary military institution with that answers to yesterday’s military discipline. After some agitation, which was unsuccessful and completely futile, he sent the prisoner to the neighboring room with a glass door, from which you could hear everything that was going on, and see the interlocutor’s behavior.

I was among the last. When I got inside, Mr. Rollet greeted me with a friendly smile and I was asked to sit down. Then, through an interpreter, a Spanish doctor, he asked me how I felt and what I was thinking next. He told me that what we were doing was nonsense. And he repeated, I guess what he proposed to others:

that we be organized into a special group and that we would receive special treatment. He told me that we are not in prison. That this is an ordinary military camp, with military discipline, but, well, we Internationals are not used to military discipline, so we that’s why it seems that we are under a prison regime.

The interpreter carefully translated his presentation for me and I listened to him until he said that we do not know what military discipline is. And then I confronted him and told him, roughly, the following:

“Mr. Captain, it is not true that we do not know military discipline. We couldn’t do without solid military discipline to fight successfully with the Fascists at all, because they were always better armed than us and in every respect better supplied, how weapons and ammunition, as well as other means for waging war. On the contrary, Mr. Captain, we had such discipline. It was the discipline of conscious fighters who know why they fight. During the fight in Spain, I didn’t have a single case where the soldier would disobey me. On the contrary, when I had to go on the most difficult tasks, I always had more volunteers than I needed to complete those tasks. I doubt that you will have such disciplined soldiers if war comes. Our soldiers respect their Officers and treat them as older Comrades, they greet them and carry out all tasks, not because the law obliges them to do so, but because they are aware that it is necessary to do so.”

This made him quite angry, so he said in a raised voice that we know little about order and discipline, that we are primitive, uncultured Balkans, and so on.

I didn’t want to be in his debt. I answered him:

“Mr. Captain, you know little about our history. That’s not our fault, it’s yours. The history of the Balkan nations says the opposite. In the Middle Ages, the culture of the Balkan peoples was at a much higher level than that of many Western peoples people, including you French people.”

When the interpreter translated my words for him, the Captain became terribly offended and simply rushed at me, saying to me in French:

“March, Communist bitch!”

Entering the other room, my friends greeted me with joy and congratulated me for giving Mr. Rollet a good lesson. Vlado Popović even hugged me.

The conversation with the last two others was very short. The principal saw that nothing could be achieved with us in this way, regardless of the fact that we were in a rather difficult condition, due to starvation and unbearable conditions in the prison.

Soon the lambs were removed one by one to separate rooms, in order to completely separate and isolate us. They wanted to deprive us of mutual agreement and collective influence, and to create conditions for processing each one individually. On that occasion, they also handed us some things from the warehouse. It was probably already planned that they would evacuate us, so they wanted to hang together less later.

They placed me in a room on the sixth floor of the eastern part of the building. It was a kind of mansard. It probably used to be used for the needs of the court servants. The room was about 5 x 6 with a larger window that looked out on the sea and with a smaller window on the opposite side. The floor was of beautiful ceramics. But, as the windows were without glass, and the room was at a great height, the draft was unbearable. At that time, a strong wind was blowing from the sea.

Across the hall was another similar room. It housed Milan Kalafatić.

After some time, the Lieutenant, Sergeant Brka and two other Guardmobiles came to visit me. The lieutenant asked me if I had any wishes. I demanded that they glass my windows, give me my blanket and, with my money, buy me cigarettes and matches.

The Lieutenant replied that I can get all that, but only on the condition that I start eating or at least drinking wine, which will warm me up.

I told the Lieutenant that I didn’t need food. Wine, too, because I’m on hunger strike, and it’s nutritious. I asked him to convey my request to the Commander and to tell him that he will personally bear full responsibility for the consequences for my health due to this kind of accommodation.

The Lieutenant smiled cynically and as he was walking away snapped to me:

“Look, please, he still dares to demand, and even threatens!”

Soon they brought me a dish on a tray, a ragout with plenty of meat, a quarter of a liter of wine, a sizeable piece of white bread like snow, and a glass of milk. For the conditions at the time, a real abundance. The smell of the food was enchanting and challenging. I demanded that they take it back immediately, because I don’t want to eat it. Once again I demanded that they glass my windows, bring my blankets and buy cigarettes. They didn’t pay attention to the others, when closing the door, one of the guards threw in a package. They put the tray with food on the window and went out. However, I picked it up and unfolded it, and to my great joy there were six or seven cigarettes, a dozen matches, and a piece of lighter box.

It was a big surprise for me. This meant that the guardmobile gave way. I had barely smoked a cigarette, when the guard Sergeant “Square Head” came in with a German International, who was also a prisoner. He soon “glazed” both of my windows with transparent, armored paper. Life will be more bearable now.

After that, they “glazed” Kalafatić’s windows as well. I called him and asked if he would like me to send him cigarettes. He answered yes. There was a black man at the guard post and when we started talking, he walked away. Kalafatić after that he called and in French asked me to transfer the cigarettes to him. However, the black man left and soon brought his cigarettes and gave him his own cigarettes. So we were both, at least temporarily, provided with cigarettes.

In the evening they brought me dinner and took away my lunch untouched. Besides they also brought cement bucket full of water. I drank water little by little, until I even looked at the food. It was already time to sleep, but the floor is too cold. I lay down for ten minutes and got up. I sit and think. If I fall asleep on the bare floor, my cold does not go away, and maybe something worse. I, on the other hand, cannot stand walking or standing for a long time. Fatigue will overcome me quickly. At one point, my gaze stopped at a closet with two smaller doors on it. I had to get really stuck to pull the door together with the hinges out of the door frame. Then I placed them on the floor next to each other, since they were quite narrow. I used the suitcase as a headboard, lay down and fell asleep.

When they brought me breakfast in the morning, Sergeant Brka was shocked by the “barbarity” that I had committed over a wardrobe of historical value. He roared and threatened. How dare I destroy their state property! Since he knew Catalan well, and quite a bit of Spanish, I answered him that I was as much concerned about their state property as they were about my life.

“After all, it’s your fault. You are not allowed to convert buildings of historical value into prisons and dungeons for innocent people.”

He kept his mouth shut as much as he could, took the untouched dinner and left. He got his own.

However, that day I had another conflict with him when bringing lunch. Brka was not a smoker, so he immediately smelled tobacco, because it didn’t even occur to me to ventilate the room.

“So you smoked?”, he asked me, “where did you get your tobacco from?”

“God is good, so he sent him to me, so that I would not suffer” I looked at him ironically.

This caused laughter among the other gendarmes, but Brka demanded that I reveal to him who I got the cigarettes from. He didn’t even allow himself to be confused, he tried to get the matter out into the open. I didn’t see the one who persistently threw cigarettes at me. That’s why even if I wanted to tell him, I didn’t know him at all. The Gendarme continued to joke with the “good God”. And when he explicitly told me that God does not come down to earth, but that some man did it, I answered him:

“Well, if a man did it, then maybe you did it, according to God’s or the Commandant’s order.

You are my most frequent visitor and guardian.”

Everyone burst out laughing. And the Lieutenant, who was standing by the door, invited him to leave his idle work. When leaving, the Gendarme who was closing the door, interjected I have almost a whole pack of “Gauloise” cigarettes and more than half a box of matches. He probably honored me because of his “fair” attitude and banter and with “Brka”.

And for the next two days, they brought us regular food, but now milk and strictly diet food, with the fact that it was prepared and served like in a hotel. Finally, they saw that it was futile, so, on the eve of the last day, they stopped bringing it.

I was weaker and weaker with each passing day, but also more cheerful. I didn’t feel hungry at all. I’m already used to not even thinking about it. Maybe I could unlearn eating, like Nasradin taught his donkey, only the donkey still farted.

On March 28, I heard when they took Kalafatić from the room across the street. I didn’t know where.

They came for me the next day. The gendarmes took my suitcase, because it was quite difficult for me to move without it. A pickup truck was waiting for us downstairs. Fadil Jahić was already there. They gave us a money and the rest of our things, put us in a truck and left the prison.

Fadil asked the undertaker what about the others? He is replied that they were all released yesterday. We are the last ones and they drive us to Perpignan, to the hospital.

On the way out of the Fortress into the city, they stopped in front of a grocer and asked us if we wanted them to buy us anything. I asked them to buy me cigarettes, and comrade Fadil ordered biscuits. They brought us what we ordered and set off on the way to Perpignan.

Comrade Fadil immediately opened the package with biscuits and asked me to take some too. I turned him down, telling him that after nine days of starvation, nothing should be eaten. I advised him to suffer a little, because we will probably get tea and cleaning products in the hospital, and then we will start eating. I nicely explained to him that now we are more in danger of eating than earlier than starvation. But that didn’t help. Comrade Fadil eyed the biscuits, telling me that he is not afraid of it, because he has a good and healthy stomach. I realized that it could be dangerous for him, so I warned him again and he, although a little offended, still stopped eating.

In the cell, a drawing

It didn’t take long, and he started to feel pain. He paled before and clutched his stomach. It’s his luck that we had quickly arrived in Perpignan and the hospital, where the doctors accepted him and immediately washed his stomach. That’s how they saved his life. If, by any chance the journey would have taken longer, he would surely have died.

On that occasion, the doctors scolded the Gendarmes for allowing Fadil to eat. When handing over the documents from the Gendarme’s conversation with the doctors, I understood that they should let them know when we recover. I was convinced that they would send us back to prison.

The whole hospital was occupied exclusively by wounded and sick people from Spain. The hospital staff — doctors, paramedics and other staff, were mostly Spaniards. Only the manager of the hospital and some department heads were French. And all of them were military officers.

The treatment towards us was very good, especially the Spanish people who treated us like our own brothers. They were informed about our struggle in prison and admired us. Lighter food the next day. Only after five days we started to eat more or less normally, but still only diet food.

And soon we recovered.

I spoke with the Spanish doctor, who, in the absence of the French hospital manager, was a kind of his deputy. I explained our situation to him and asked him, when the warden is not in the hospital, to include us among those who have been written to return to the Argeles camp. In this way, they would avoid being returned to Collioure prison again. He agreed and promised to do so.

On Sunday, April 9, on Easter, the doctor quickly checked us out together with other Spaniards, they were sent to the Argeles Camp in an ambulance. I thought we were saved. We talked to our Comrades from the Party Committee to help us escape from the Camp, as we were convinced that they would send us back to prison. Our Comrades told us that a directive had arrived not to escape from the Camp. It was difficult for me to understand the justification of such a directive. But we had to put up with it. We also spoke personally with the secretary of the Internationals Camp Party Committee, Otto Flatter. And we got the same answer from him. What’s more, he was even a great optimist and said that outside there was a big press campaign about our hunger strike, and that the French would not dare to imprison us again. If they even come for us, he told us, they will take appropriate measures to prevent them from doing so. We trusted Comrade Flatter and our other party leaders. We did not want to violate the party directive, on which their decision was based. That there was no such thing we would manage ourselves or at least try. After all, in those days it was not difficult to escape from the Camp, even in broad daylight. But discipline is discipline. Upon arrival at the Camp, we also learned about the fate of the other comrades. The eight were sent to two Camps (four each) in Spain, while Franjo Serafin and Kurt were in another hospital in Perpignan, and Aca Mirić Caballero and Peko Dapčević were in a hospital on a boat in Port Vendres near Collioure.

On the afternoon of the fourth day, a whole bunch of armed Guardmobiles came with unsheathed clubs in their hands. They called us and ordered us to pack up and go into the “Paddy Wagon”. It was sudden. No one moved a finger to resist them. We were a little surprised, but what can be done. The promise was just a “promise — crazy joy.”

They took us back to Collioure prison. They’d already brought Caballero and Peko Dapčević there. They separated us by sections, among Spain.

Through Dapčević, who served as a translator, Mr. Rollet cynically asked me:

“Do you know why you are in prison now?”

I answered him that I now know as much as I did before and that I consider it a simple lawlessness.

To that he said to me:

“Now you have been arrested on the basis of the law, because you violated it by protesting and declaring a hunger strike.”

Then he asked if we intended to hunger strike again; I answered him that we will see about it. But, if there is a need for a strike, you will be notified in time.

We expected that they would also bring the others to prison. In that case, it would be worthwhile to renew the strike. However, it only ended with the four of us being sent back. Still, it’s a success. Ten of our comrades were saved from the torment of this infamous prison, which was getting worse.

They brought in new people every day. There were mostly Spaniards, but also a lot of Internationals. Sometime in June, the prison was already overcrowded. There were over five hundred of us. In addition to adults as prisoners, a whole company of Spanish minors was also brought. There was a special regime for them, somewhat milder, but still not humane, given that they were children from 10 to 17 years old.

The rooms where we stayed and slept were too full, so we were packed like sardines. We slept on the floor on straw, which was changed only when it turned into dust. In addition to other things, our life has been made worse by the lice we couldn’t get rid of. Even though we killed them every day, they just kept on us.

Beatings were a constant occurrence. Every day, some inmate was beaten, without any serious reason.

The food was simple, but quite deliciously prepared. However, for a large number of people, especially young people, it was absolutely insufficient in terms of quantity, as much as before we had to work a full 8 hours a day at hard physical work. Because of this, people suffered, became weaker and less energetic. In addition, taking food was a kind of harassment. They fed us not far from the toilet, which smelled terribly. The cauldron was reached one by one, along a narrow path fenced with barbed wire, which passed by the toilet itself. The tireless sergeant Brka was usually standing by the door. He supervises the cooks during the distribution of food. But Brka often had the habit of beating prisoners on the hand, because the latter approached the cauldron improperly, for not greeting him by taking off his cap, or for looking at him grimly. The reason for this was always easy to find. Upon receiving the meal, each the section went to its designated place in the yard and quickly finished the meal there, sitting or standing. Because it was necessary to wash the portions in time and wait for the invitation to enter the room, for rest. And, we always went on break after the end of the working day from 7-12 in the morning and from 15 -18 in the afternoon, that is, on holidays from 7-11. That’s how our days progressed, which were getting harder and harder.

One night, as I remember at the end of June, when I regained consciousness, I saw that I was in a bed in the infirmary. I was amazed. The Spanish doctor was next to me and looked quite upset. I was drenched in cold sweat and completely weak. During the conversation, he explained what happened to me. Around 11 o’clock while I was sleeping, I started gurgling and suffocating. My friends heard this, alerted the guard and took me to the infirmary. He did everything he could to bring me back from unconsciousness. He told me that my heart was not right and that I had to be careful.

I stayed in the clinic until the morning, and then the doctor told me to go to his section and to come around 12 noon to get a new pill. If I get sick before that, I should contact him immediately.

During the morning I was at work, together with other comrades. We were arranging the field in front of the entrance to the Fortress. I was in the shade more than I was working. Because my section chief also found out what happened to me at night, he told me to take cover from the sun.

Around noon, I came to the infirmary and encountered a French doctor, a Lieutenant of the Guardmobile. He asked me what I wanted. When I answered that the doctor told me to come and take the pill he had prescribed, he lashed out at me:

“What doctor? I’m the only doctor here and no one else!”

“A Spanish Doctor”, I told him. “He saved me from being suffocated last night”

At that, the Spanish Doctor came and explained to him what was going on, he gave me a small pill which I swallowed. The Doctor told me to come again tomorrow for the pill.

That’s what I did. All, again I ran into a French doctor, a Lieutenant. He scolded me and rushed me, telling me that he is the only one who prescribes medicine, and that I am healthy and an ordinary faker.

I answered him:

“Mr. Lieutenant, when you see me again in your room infirmary, you can order me to be put in jail immediately.”

Call that doctor, he was worse than all the gendarmes in this prison. After the case with me, he accused the Commander of two Spanish prisoners of being dangerous fakers. As is the order in such cases, Commander Rollet sentenced them to 10 days each in a prison cell – a dungeon in the Fortress wall. The sentenced was read in front of the formation. During the reading of the order, both Spaniards fainted from excitement and fell to the ground. Certainly, there was no simulation. They were immediately transferred to the prison clinic. At the end, the imposed sentence remained in force. They had to endure it, only that, instead of a dark cell, they were put in a clean and bright room, specially arranged with hospital beds, where they were treated by a Spanish doctor and where they received better and more abundant food during the entire sentence.

Somehow, right at that time, one afternoon I got sick again. I was in the sun a little longer. My friends from the section accepted me, took me to the shade and cooled me down with water. At that moment, Captain Rollet, his adjutant and the French medic came by.

The Doctor ran up and grabbed my hand, probably to check my pulse. I tore it off and told him that I don’t need his help, that we have enough Gendarmes without him, and that I don’t want the Gendarmes to be my doctors. I also told him that just a few days ago he rushed me out of the infirmary like a simian, and that the same was done to those two sick Spaniards.

When the Commander intervened, I asked them to bring a real doctor – a Spaniard, whose help I will gladly accept.

Soon he nursed me and gave me some drops, so I’m coming to get pills again regularly. Because I didn’t want to say that I was going to the infirmary, he was going to treat me in the yard.

A few days later, the French Doctor was dismissed. It seems that it was also clear to them that he was overreacting with his actions.

The reporting system in this prison was introduced from its inception. The prison administration made sure to provide its own informants in each section. Only we were really careful and quickly found out who the informers were.

However, one day two Catalan officers and Peko Dapčevic set up such an informant. They were invited to the office and the French, instead of thanking them for their hospitality, were duly beaten, allegedly because they had insulted France. Comrade Peko could not bear these humiliations, so when he left the management office, he spoke in Spanish at all costs. shouted:

“Comrades, these are real bandits and executioners! They beat us without any reason or fault!

How long will we put up with it?!”

At that moment we were all in formation. The Gendarmes spoke quickly. They grabbed Peko and both Catalans and dragged them back to the Administration premises. Gardmobiles ran outside armed with rifles and surrounded us, to prevent a riot. Immediately afterwards, they took us to our rooms and locked us up.

They nearly beat Dapčević and his fellow Catalans to death, and then transferred them to prison. The next day, as a punishment, they were transferred to the penal section, which was under a special regime. Namely, they were isolated from other prisoners, constantly under guard from morning to night and under beatings, they did the hardest and dirtiest jobs.

Shortly before, Fadil Jahić had started working as a carpenter. He also had a very good boss. He seems to have been a supporter of the Socialist Party. He often expressed his affection for us in front of him and condemned the actions of the Gendarmes. That is why I told Comrade Fadil to ask his boss if he would like to do us a favor and take the letter that we are going to write outside of Collioure and drop it in the mailbox, so that it would reach the newspaper “Humanité” without prison censorship. It’s a risk, but we trusted his honesty. And we were not deceived.

Fadil’s boss promised to take the letter all the way to Perpignan and drop it in the box there. He told Fadil to write immediately, because he is already traveling in the afternoon. Namely, he asked and got permission to go home, because supposedly his child got sick.

In the letter, I described our situation in prison in detail. I personally described the actions of the prison authorities towards the Catalans and Peko Dapčević. I asked the editors to do what they can to stop such criminal actions. I wrote the letter in Serbian, and at the top of the letter, I put a note to the editors about it.

After the events that took place, Mr. Rollet tightened the regime even tougher than before.

He conferred with his Gendarmes and reprimanded them and leniency, encouraged them to be stricter, because, supposedly, the prisoners abuse their leniency.

For a couple of days, it was Sunday morning, before they were brought out to work with us, the Commander Rollet ceremoniously presented each guardmobile with a horsewhip woven from willow branch. Then he ordered them to always use them on the prisoners when they were unruly. Probably, so people wouldn’t hurt their hands. After that, as usual, they took us out to work outside the prison.

However, in the town of Collioure there was a real upheaval In the garden of a tavern, which was located right next to the exit from of the fortress, barely fifty meters from the main gate, there was a protest meeting against abuse of prisoners in the fortress. The protest meeting was called by the People’s Front, led by the Communist Party.

When the Prison managers found out about this choir, they quickly returned us to the fortress and locked us in our rooms. Although we didn’t know the real reason for returning from work, we had a hunch that something unusual was brewing in the city. Soon, we heard loud noises coming from the direction of this tavern loudspeakers intoning first our Republican anthem “De Riego”, and then “Hovengvardije”, “Internationale” and “Marseillaise”, and later the sounds of other revolutionary songs and marches. So we could also hear the noise of human voices from the meeting, which was lasted somewhere from 10:30 a.m. to almost 1:00 p.m., and then gradually, everything calmed everything down. After that, they took us out and gave us lunch.

We noticed the Gendarmes without their waistcoats. Looks like they got them at an inconvenient time. We never saw them with them again.

We found out later that they contributed to the protestors sheets of “Humanité”, “Ce Soir”, “Popular” and others that had published a large number of information and comments with large headlines about the situation in our prison. Among other things, there was also information from prison that were sent in a letter under my signature to the editors of the newspaper “Humanité”. There were even photographs of prisoners in the courtyard. These photographs were probably taken by soldiers from the window of the building in the fortress. At the meeting, the public of the city of Colliour strongly condemned our torturers. There were even calls to all of them wanted to rush us out of prison. Of course, that didn’t happen. But the regime change in our prison happened very quickly.

The Prefect of the Department from Perpignan came to visit us the next day. He was a member of the Socialist Party. Since he got involved with the situation, he ordered with terror and harassment of the prisoners to stop. In a conversation with some of the prisoners, he promised that the situation would change quickly, that he would order that the causes of being brought to this prison be investigated individually, and that those who were not guilty would be released and returned to the camps.

After him came the commandant of all the Spanish prison refugee camps, by rank army general. This old and honest soldier did not hide his great displeasure when he got acquainted with the state he saw at first sight upon entering the court of our Fortress. The wire passages in the yard, in front of the toilet, immediately caught his eye, so in our presence he asked Captain Rollet why they needed to install them. The Captain gave him some explanations, but he did not agree, so he ordered that it be removed immediately. And when he got acquainted with the other conditions of life in our prison, he acted like the Prefect of Perpignan. It seems that the General received the appropriate directive to liquidate the current situation.

The regime suddenly relaxed. The food has improved, the prisoners have come alive. They no longer separated us from each other, but we could mix and talk with each other. In order to cool us down a little in our excitement, Mr. Rollet took advantage of the arrival of another General, who was probably his acquaintance. On that occasion, in front of the formation of prisoners, this General gave a threatening speech, so among other things, he also said that we should not pretend to be too naive and innocent angels, because we are all political criminals and very dangerous for the social order of their country, etc.

When it was over, a Spaniard asked him a question :

“Mr. General, let’s agree with you that, yes, we are not angels, but political criminals and very dangerous for society. But, please, is it possible that you also classify these children as dangerous criminals? Will anyone believe you that even these small and weak children are politically dangerous for French society?”

The general looked in the direction of the company of minors, turned around to us with his head and, as it seems, he was very uncomfortable that he was tricked into appearing in front of us like this. He turned to Mr. Rollet and whispered something to him, and then he turned to us again and said:

“Well, they will be released soon.”

And, indeed, soon the minors were taken out of prison.

And Captain Rollet, as well as some Guardmobiles, also disappeared. The new Commanding Officer, the Captain, came, and with him also a Guardmobile comrade. After that, a certain number of Spanish prisoners were released, mostly elderly and sick people. The number of prisoners has significantly decreased. The regime has become much milder and more accommodating.

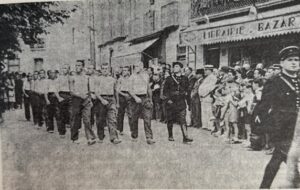

The town of Collioure, July 14, 1939. Parade of International camp inmates on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of the French Revolution

They divided us into rooms. Now there are much fewer of us, so it was more comfortable. The rooms were disinfected and cleaned. They gave us new straw and sheets, and plenty of soap for washing. We all tried to clean ourselves as soon as possible. We didn’t even go to work those days, so we soon got rid of the lice. In addition, we received new, blue, worker’s trousers and shirts. We were all nicely uniformed. On July 14, 1939, they took us out to the city and lined up on the square in front of the Fortress, where the ceremony of the 150th anniversary of the Great French Revolution was held. Photographers took pictures at that ceremony, so we recently received the pictures. And we keep those pictures as a memory of that day. Work became easier and food better. Several times they took us swimming, to the city beach. Everything was much better than before. Sometimes some of the Spaniards would be released and leave the prison. After all, these were people who were released on the basis of special interventions. Since our release, based on the investigation of our crimes, there is still nothing.

However, this state of affairs did not last long. Already in the middle of August, to our great surprise, Captain Rollet returned and took the position of Prison Commander again. With his caress, the gradual tightening of the control began again. However, it was much easier, because he was not allowed to return to his old relationships.

This led to international tension.

Hitler was preparing an attack on Poland. Negotiations between the Soviet Union and England and France were terminated. The Soviet Union signed a non-aggression pact with Hitler’s Germany. There was real confusion and misunderstanding of that act among the Spaniards. We were confused too. The anarchists, of whom there were also quite a few among us, raised their heads and, together with the Gendarmes, attacked us, the Communists and the Soviet Union.

We defended the policy of the Soviet Union as best we knew how, even though we ourselves were not convinced of the justification of concluding a pact with our blood enemy. However, we believed that there were some deep reasons for such a procedure. Lately, I have received a fragment of an article, if I am not mistaken, by Mr. Eduard Erio, which appeared in a Marseille newspaper. In it, Mr. Erio evaluated the action of the Soviet Union as a consequence of the badly conducted policy of the governments of England and France. Namely, they were conducting negotiations with the USSR for the conclusion of a non-aggression pact, but in such a way that it does not come to that pact at all. According to the author, the governments of England and France wanted an agreement with Hitler and promote a confrontation between Germany and the USSR.

Soon there was a German attack on Poland, and immediately after that, a declaration of war between France and Germany. Mobilization was carried out in France and a state of war was declared. The state of war brings with it other consequences, and for us prisoners it meant a tightening of the regime.

But the French needed willing allies to fight against Hitler’s Germany. And who could be a better fighter against fascism than us Internationals and Spaniards! Mr. Rollet probably received the appropriate directives to invite us to enroll in volunteers for the defense of French “democracy.”

And our Prison Committee of the Party, which was organized during the period when we could breathe more freely, and worked quite well in the illegality, received a Party directive that all of us should enroll as volunteers. That directive allegedly came via a special courier from the Communist Party of France, with which the other parties were supposedly in agreement. We have already heard something about the alleged split in the Communist Party of France, which occurred after the conclusion of the pact between the Soviet Union and Germany, but we did not know exactly the true state of affairs.

When Peko Dapčević, whom we delegated to the founding committee, informed me of the aforementioned directives of the KP of France, I was quite surprised. I could not understand that the Communist Party of France could issue such a directive. It would have been a different matter if they had first released us, and then asked us to fight for France. He told Peko to convey his opinion to the prison committee. Namely if we already agree to enroll in volunteers, then certain conditions should be set, such as for example, that we be organized into Interbrigades, with our own command structure, the committee accepted that opinion. Then, all comrades were asked to set this condition when registering.

Commander Rollet, later, lined us up and gave a fiery speech about the fact that now is the time to show in action how much we care about freedom and the defense of French democracy against Nazism, and invited us to enroll in the volunteer service . Delegated comrades presented our conditions. Miraculously, Rollet stated that he has nothing against the creation of Interbrigade units and that this is completely understandable. After his statement, we all signed up as volunteers for the defense of France. The exception was about twenty anarchists, who declared that they did not want to enroll with us. Other anarchists also signed up.

Thus, we became allies, “comrades in battle”, even though we were under guard and still in prison. Admittedly, relations with the Gendarmes became almost friendly, so Commander Rollet was also very pleased and proud of his success and, as it seems, was happy that we became “allies”.

But with the education of our brigades, something was delayed. Rollet explained to us that it is necessary for some time to pass until a decree on this is passed in the “Official Gazette”. Only then can he proceed with the formation of our units.

Finally, that hour has arrived. The decree was promulgated. In the afternoon, they were supposed to read it to us and call us again to register. Our prison committee also received a directive from the KP of France, which was conveyed to me by Peko Dapčević. According to the decree of things, Foreign Legions are created, on the basis of already existing legions, as well as with everything else that is foreseen for the Legion and Legionnaires in terms of rights and obligations. The directive was to enroll in the Foreign Legions.

I immediately told Comrade Dapčević that I would not obey such a directive, even if it came directly from the Comintern, and not from some dubious party committee from a French province. I told him that it was beneath my honor to be a Legionnaire, and that I would not enroll. I also advised him not to join the Legion, and I also asked him to fight for the amendment of that directive in the committee.

Dapčević immediately relayed our conversation to the committee members. They discussed it and passed a new directive according to which no one should apply for enrollment in the Foreign Legion.

Soon after that, we were lined up in the yard, usually in sections. Based on the earlier results, Mr. Rollet was convinced of the complete success of his campaign. To make this moment as solemn as possible, he also invited some of his supposed elders. Then he gave us a short patriotic speech and read the decree of the French government and the military ministry. When he had finished reading, in a solemn voice he invited us to declare and enroll in the Foreign Legion and to contribute to the defense of the French Republic against the German Nazis. During his speech, Rollet avoided using the word because he himself was of that political conviction, “fascist”.

To his great surprise, there was a deafening silence and no one wanted to answer. Everyone remained silent and remained in their places. He was very confused and surprised. He repeated his call and reminded us that, just a few days ago, almost all of us signed up as volunteers for the defense of France. He asked what it should mean now? Why are we silent? Why don’t we answer? He suggested that all those who want to enroll, two to one side.

Only after a long pause, a dozen anarchists stood out. It was only a small part of those Spanish anarchists, who last time they didn’t want to join the volunteers, when we all joined reported, understandably, on the condition that we defend France organized in special Interbrigades.