ON THE NORTHERN FRONT by Vojislav Milosevic

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War

It was assembled by Editor-in-Chief Cedo Kapor and published by the Initiative Committee of the Association of Spanish Fighters, The War History of our Peoples, Book 130, Military Publishing Institute, Belgrade, Yugoslavia, 1971, 5 volumes.

Chris Brooks made several minor edits and added additional footnotes for clarity.

ON THE NORTHERN FRONT

Vojislav Milosevic[i], Spanija, V2, pp 319-331

At the end of October 1936, I traveled from Bordeaux with a group of volunteers by train to La Rochelle, where we arrived before nightfall. Three friends waited for us there and took us to a nearby pub. We refreshed ourselves and had a snack in it. At around 11 o’clock at night, we left the tavern and headed for the pier where, after a short wait, we boarded three fishing motorboats and transferred to a ship of the Spanish Republic, which was anchored offshore outside the harbor. (That ship was actually evacuating children from Spain to France.) When boarding the ship, we were ordered to enter the cabins and not to appear on deck for the duration of the trip.

The ship left the waters of the port of La Rochelle around 4 o’clock in the morning and headed for Spain, accompanied by an English and an American destroyer. The destroyers followed us until 6-7 kilometers in front of the Spanish port of Bilbao, and then they left us.

When we disembarked, we were greeted enthusiastically by a crowd of citizens. Then we were approached by representatives of various political parties (nationalists, communists, socialists, anarchists) asking us, according to our political convictions, to choose one of them, although all these political parties fought for the Republic and against Fascist and monarchist rebels. Understandably, all the Communists approached the representative of the Communist Party of Spain, who immediately took us to the municipal building of the city of Bilbao, where their premises were. There we were warmly received by the comrades who worked in that committee, and after a pleasant conversation and reception, we were taken to the “Quartel de los Capucinos” barracks. In fact, it is a Capuchin monastery on the outskirts of the city, converted into a barracks. In the barracks around 1,000 people were gathered, mostly Spaniards. That’s where I got my Spanish name – Mariano Valdes.

After a few days spent in the “Quartel de los Capucinos” barracks, where we had a good rest and where we had the opportunity to familiarize ourselves with the conditions in Bilbao, we were invited to the command of the city. There they were interested in our military education so that we could be assigned to units. The largest number signed up for anti-aircraft artillery. I signed up as an infantry-machine gunner, because I served my military service in the infantry in the former Yugoslav army and trained as a machine gunner. After our enumeration, we returned to the barracks.

Although we were given military uniforms and rifles on the second day after arriving at the barracks, we were allowed to go out into the city every day for leisure and getting to know its population and cultural values. During those outings, I noticed that the city lived an almost normal peacetime life, as if the war didn’t exist at all, even though the front was only 45 kilometers away and even though enemy planes often flew over and machine-gunned the unprotected city, because there was no anti-aircraft defense, artillery and PA machine guns. The store functioned normally, although there was a shortage of many items, the cinemas were open, the cafes were noisy, and in the parks you could always see people walking or resting. Since we had some French francs, we had the opportunity to spend time in the city. Namely, these were savings from France, because for the entire time we were in Bordeaux, we received a daily allowance of 12 francs from our organization, in addition to food and accommodation in a hotel. While my friends usually went to bars, I went to the cinema. I was modest in my needs, so I had a lot of francs saved up, but because of that I also had trouble with an Englishman who liked to drink, so he kept asking me for money (later I found out that he escaped from Bilbao and came to Spain as adventurer).

In the city, I met the sympathies of the citizens and in those encounters, I felt their respect for internationals. This is certainly because we, exposing our lives, have come to help them in their righteous struggle.

Through talking with the Basques in the barracks and in the city, I got the impression that the Basques are a very dignified and civilized people and that they are proud of their history. Basques inhabit three Spanish provinces: Gipuzkoa, Alava and Biscay. The capital is Bilbao, located in the province of Biscay. Álava is the largest by area, but Gipuzkoa and Biscay are the most populated Basque provinces.

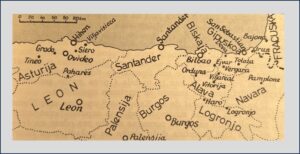

Map of Northern Spain

Biscay and Gipuzkoa are next to the sea, rich in coal and iron and have a relatively developed industry. Their foundries are famous and they also produce weapons and ammunition. There were about a million Basques then. The largest number are peasants (40%), followed by workers (30%), then artisans, officials and other professions (30%). The Basques value freedom the most and are proud of the fact that they were the only ones not conquered by the Moors on the Iberian Peninsula. Throughout the Middle Ages, they had their own independent state and, for those times, very advanced legislation. Now, on the other hand, they are delighted with the autonomy obtained on October 1, 1936, when the parliament of the Spanish Republic approved the statute for the Basque Country (Basconia). The president of the Basque regions is Jose Maria Aguirre, a representative of the Nationalist Party, which is also the strongest. After them in terms of strength are socialists, then communists and anarchists. The Basques are particularly proud of Dolores Ibaruri, La Pasionaria, who is from their midst.

After ten days of stay in the barracks, where everything was reduced to military training, and less to political-ideological work, we were invited in groups of 5-6 people for an interview with the Soviet representative Goriev.[ii] Goriev was also interested in our military education, gender and service, as well as in our biographical information. During the conversation with Goriev, one interesting scene remained in my memory. Namely, during the talks, the artillery bombardment of Bilbao by Franco’s navy began. Explosions echoed in all directions. One flying shell broke through the roof and fell on the attic of our building. Surprisingly, it didn’t explode. One of the Spaniards, who happened to be there, grabbed that grenade and wrapped it in paper and brought it to the office near Goreiv. The grenade was still so hot that it

soiled the paper, and the Spaniard’s hands were enveloped in steam and smoke. It looked like it was going to explode at any moment. That scared us, so we all ran out of the room, except a Spaniard, who also called us cowards. After a few seconds, when we regained our composure and realized that the grenade would not explode, we returned to the office. Humiliated and ashamed, we looked at the 150 mm caliber grenade that our Spaniard held with dignity in his hands. For us, it was also the first test of mental and nervous endurance in the face of mortal danger.

In the “Quartel de los Capucinos” barracks, I met the German Neumann, who worked as an expert on weapons training. I asked him to help me go to the front as soon as possible, because I did not need longer training on infantry weapons. He helped me with that, so sometime after November 20, 1936, I was sent to the shock battalion that bore the name of a Spanish leader, “La Raniaga”. Around 200 people from the barracks went to the front. Moving towards the front, we met transports of the wounded who were being transferred to Bilbao, to the hospital. Whenever they met an ambulance or a truck with wounded people in it, something would startle me and some dark forebodings would take hold of me. I would have preferred to have arrived at the front in a good mood and with a song, but war is not a trip to nature.

Upon arrival in the battalion, I was assigned to the 3rd company, where most of the foreigners were Czechs. However, the largest number, both in the company and in the battalion, were Spaniards. The company also had its political commissar, whose name I no longer remember. The company commander’s name was Antonio. The May Battalion, deployed in a position towards Guernica, led defensive battles for the city of Bilbao. The area where the defensive battles were fought looks reminiscent of our Dalmatia. It is a rocky and unforested area with occasional low scrub.

The very next morning, we newcomers experienced our first baptism. The enemy attacked our positions with an artillery preparation of about a minute. We welcomed and repulsed him. But the enemy was not satisfied with that. With the support of the Italian army, and during the day also the aviation, they organized several assaults with the aim of throwing us out of our positions. The fight lasted all night, but the Francoists did not manage to suppress us. And most of the victims were from artillery shells and airplane bombs.

We remained in these positions until the end of November. The enemy made occasional attacks, but we always brought him back to the starting positions with our help. Lieutenant Neumann visited us from time to time, in order to check the correctness of the weapons. I enjoyed meeting him, because he was good and attentive

mate. Unfortunately, he died after a month driving in a car that was machine-gunned by an enemy plane. At that time, I also met some of our Yugoslavs. Radovan Pavlović left France for Argentina. Along the way, he stayed in Spain, and when the general rebellion broke out, he joined the Spanish communists to defend the Republic. The other introduced himself to me as Miloš (I forgot his last name) from Split. I learned from them that there are about 15 Yugoslavs in our battalion. I met some later, but I forgot their names.

Preparations for the offensive of the Republican forces in the north began after my arrival at the front, when General Llano de Encomienda came here, whom the Republican government had appointed as the commander of all units in the north. Reinforcements in manpower and weapons were also obtained. At that time, the front stretched from the sea to the border line of Biscay with the provinces of Gipuzkoa, Álava and Burgos, further along the border line of the province of Santander with the provinces of Palencia and Leon, and from there through Asturias to the cities of Oviedo and Grado. The goal of this offensive is to attract enemy forces from the south and weaken the pressure on Madrid, which has been resisting the violent attacks of Franco’s troops since November 6.

The offensive of the Republican forces in the north began sometime in early December in all sectors simultaneously, in several directions: from Biscay towards San Sebastian, Vergara, Vitoria and Burgos; From Santander towards Burgos; from Asturias towards Galicia and Leon. The fighting was very fierce, because the enemy was persistently defending itself. Nevertheless, the Republican forces broke through the enemy’s defenses on all offensive lines already on the first day. In a few days, most of the territory of the province of Gipuzkoa and a good part of the provinces of Avala and Burgos were liberated. The troops from Asturias penetrated deep into the province of Leon, cut the road to Oviedo Grado, and penetrated about 45 km to the east towards Galicia. Being frightened, the enemy withdrew his forces from Madrid and transferred them to the north with the aim of stopping the further encroachment of the republican forces on this front, which he achieved. The goal of the Republican government has been achieved. Limited success was achieved in the north, but the defenders of Madrid could rest, because the enemy’s pressure weakened.

Since the enemy failed to regain the lost territory after many attempts, the front somehow stabilized with organized occasional attacks and counter-attacks from both sides. Both sides have fortified themselves well. My battalion was on the Irun front towards San Sebastian. We remained in that position until the end of February 1937.

After solid preparations on March 31, 1937, General Mola’s troops launched a new offensive in the north with the aim of liquidating the Republican forces in Biscay, Santander and Asturias. The enemy went into this offensive with 50,000 well-trained, equipped and armed soldiers. In my battalion’s sector, the attack began early in the morning with artillery and aviation preparation, and later infantry support. I remember that morning it was quite cold with frost. The attack was so violent that the enemy managed to break through our defenses and force us to retreat. We stopped somewhere in front of Guernica and Durango, where we offered him strong resistance. The fighting during April was very tiring and exhausting. However, in April, the enemy troops organized an offensive again and exerted strong pressure on our units defending Biscay and approaching the city of Bilbao. The battles for Biscay and Bilbao lasted more than two months, until June 19, 1937, when the enemy managed to break the ring around Bilbao and finally conquer it. That defeat fell hard on us, and the Basques, who were proud of their capital, experienced it the hardest.

After the fall of Bilbao, my battalion retreated and took up positions near Valmaseda. During one enemy attack on our position, I lay in a shelter made of stones and punished the enemy soldiers who were attacking. Next to me, in the immediate vicinity, were a Spaniard and a Czech, Vaclav. We were well covered and masked and there was no danger of bullets from rifles or machine guns. But the enemy was also shooting at us with artillery, using shrapnel shells. At one point, one exploded above us. The shrapnel pierced my helmet and buried itself in my head. That blow simply paralyzed me, I lost my strength and was powerless to get up and pull myself away. The Spaniard and Vaclav came to my aid and dragged me to the medical dressing station. In the dressing room, they were not allowed to take off my helmet, because they could not see from it the position of the shrapnel and how deep it had buried itself. They were afraid of injuring one of my brain centers, so they immediately sent me with a helmet to the military hospital in Santander.

When I arrived at the hospital, the doctors immediately examined me. They took off the helmet, removed the shrapnel, and cleaned and bandaged the wound. However, everything ended well. The shrapnel did not penetrate deep into the head. If it wasn’t for the helmet, who knows how I would have made out. The doctors told me that a concussion was a bigger consequence, but that it would also disappear quickly. And indeed, within a few days I already felt better. Only the eyelids on my left eye twitched, but that soon stopped.

I stayed in the hospital until the middle of August 1937. The time spent in the hospital remained a pleasant memory.

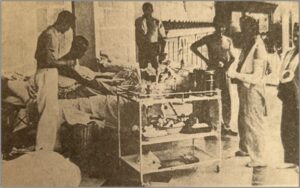

Dressing the wounded in the hospital

The doctors and hospital staff were very attentive to the wounded and sick, and the food and accommodation were good. I met many friends there and became friends with them, so my time passed faster chatting with them. Unfortunately, I forgot their names. We were mostly informed about the situation on the fronts through the press, and we especially followed the events on the northern front. Every day we commented on the information about the offensive of the Republican forces near Brunete, which lasted from July 6 to 25, and which made it possible to weaken the pressure of the enemy on the northern front. In our imagination, we wished for the joining of our southern and northern forces and the splitting of the territory held by the enemy. This pleasant atmosphere in the hospital was disturbed one day by the news that there were Fascists among the doctors and hospital staff. This scared us a little, so we were careful according to the advice of the doctor and the staff.

In mid-August, I left the hospital and went to my unit. It was, somehow, at the time when the enemy organized a new offensive against our forces in the north, with the aim of conquering the province and the city of Santander. In that offensive, the enemy used 106 against our 60 battalions. In addition, their troops were far better technically equipped, and they were also abundantly supported by aviation. The pressure was very strong, so we constantly retreated under the fighting, until the enemy managed to cut the Santander – Torelagua communication, which leads to Asturias, and to break out to sea. That way it worked for him to surround a number of our battalions and definitely liquidate them, on August 23, 1937, when he captured the city of Santander. Even the Republican offensive near Belchite, which began on August 24, could not help these battalions, but it eased the situation for the rest of our forces, which were still retreating.

Retreating, one day my unit found itself in Torrelavega. I was quite exhausted from the constant movements, fights and disordered eating. I looked quite miserable when I met Viktor Sidorov, a Ukrainian, whom I had met earlier in the city. Viktor was in the company of his friends, several Czechs and Russian emigrants, who were in a sabotage group. They grabbed me by the arm and took me to Vasili, the leader of that sabotage unit, also a Russian. They pushed me to stay with them, convincing me that it would be much better and easier for me with them. In fact, they all looked good, far better than me. I hesitated a little, but then firmly refused. I didn’t want to separate from the unit where I had already bonded with the people.

Somewhere at the end of August, my unit was defending positions in front of the town of Cabueringa. Enemy aviation was very active in that sector. During one of their raids, I was contused by an airplane bomb. They pulled me out and sent me to the hospital located in Gangas de Onis. I stayed in the hospital for only a few days, until the arrival of a senior Spanish officer (Commissar), who picked up all the Internationals and took them to Gijon, in Asturias. There were 15 of us in the group. That was at the time when a new enemy offensive began in the north by crossing the Dede and Selia rivers.

In Gijon, we found a large number of Internationals who attended the anti-aircraft artillery school, which was located in the village of Deva, about 6 km from Gijon. In that school there were also comrades whom I met back in Bilbao, who then registered with the local command as artillerymen. We were also included in that school. We took shooting lessons. The teachers were Russian and had Spanish ranks. I remembered Captain Antonov, the head teacher and lieutenants Ivan and Vasha. It was explained to us that ships with artillery and PA weapons should arrive in a few days. Unfortunately, those ships never arrived. They were rumored to have been sunk by Franco’s navy.

In mid-September, while advancing through Asturias to the east, enemy troops cross the river Pilonia, thus endangering the city of Gijon itself. Seeing that we are useless at school, I and 6 other friends (1 Czech, 2 Dutch, 1 German and 2 Danes) agreed to ask for permission to go to

the front. We went to the headquarters, which was located in the suburb of Gijon, in La Guia, to a Russian instructor from whom we got the permission. He explained to us in detail the situation at the front and said that the ships with weapons would certainly not come. We left Gijon and headed towards Villaviciosa. Somewhere halfway, between this place and Cangas de Onis, we joined the “Guardia de Asalto” battalion. It was a police unit, but in these difficult moments it was also sent to the front. As soon as we attached to the unit, we immediately entered the skirmish. The enemy was much stronger, so day by day he pushed us, all the way to Villaviciosa. We fought persistently for this place, but it was absurd, because the enemy was attacking us and from the sea, transferring his units by ship. Villaviciosa had to fall into the hands of the enemy.

After Villaviciosa fell, we had another difficult clash with the Franquistas in the next position. There we fought hand to hand. Then we were completely shattered. There was demoralization and desertions. All this took place in the second half of October. I saw that we were definitely cut off from the center and that this was the end of the free territory in the north. Everyone realized this, so they left the units and saved their heads as they knew how. I realized that I can only get my head out if I arrive in Gijon on time.

When I arrived in Gihon, I saw such a scene that I could not imagine even in my dreams. There was a general commotion. Everyone, both citizens and the army, rushed to the pier, where several ships were anchored. I went straight to the school administration. I thought I would find my comrades and Russian instructors there, who would probably organize our evacuation.

However, I did not find anyone. I assumed they had already evacuated. I went back to town and went to the pier. They boarded the wounded, they did not accept others. There I met the Bulgarian Arsen Vasev, whom I met at school. We agreed to look for a way out of this situation together. He assured me that there was a way for us to get out, but first he had to go to school to get his things. I waited for him until 9 pm, but he did not appear. At one point, my Spanish comrades from the “La Raniaga” Battalion came by and invited me to join them. They were accompanied by 1 Czech, 1 Dutchman and 2 Danes. They explained to me that there was a private fishing boat anchored offshore. It had an armed crew. They have already asked the owner of that ship, but he has refused to transfer them. It will be necessary to we force it with weapons, if he refuses again. Several armed Spaniards got into a boat and rowed towards the fishing boat under the protection of darkness and fog.

Soon we heard some gunfire, and then everything fell apart. After some time, two boats docked at the shore. We took them to the fishing boat in two groups. There we found out that there were two crew members on the ship who refused to accept their comrades and opened fire on them from the gun. On that occasion, one was wounded in the shoulder. However, the Spanish comrades jumped on board and liquidated the crew.

We are sorry that it ended that way, but our dear Spaniards could not help themselves, especially when they wounded our comrades. There were a total of 32 Spanish Republican soldiers on board. The Captain of the ship was a Spanish soldier. He immediately imposed strict discipline, arranged us around the ship and ordered us to open fire on any enemy ship or boat that approached us, to fight while we had ammunition. However, the position was quite uncertain. None of us were sailors, and except for one Spanish old man, none of us even knew how to steer a ship. But we didn’t need much navigation, so it’s obvious to us where to orient ourselves by the stars.

We went out into the open sea and headed towards Bordeaux. We did not stay close to the coast, because the enemy would have detected us. The steamship moved quite slowly, max 10-15 km per hour. We had water on board for a few days, and in fact, garbanzos. In addition, each Spaniard also brought other food, so that was shared equally with everyone. Poverty and hunger will not trouble us.

When we got to open air, at one point I looked at my friends. The tension passed, they relaxed and stared blankly at Gijon from which we were moving away. I believe that they, like me, were thinking at that moment about the fate of those who remained in the city. Not only the fate of the fighters of the Republican army, but also the great people of the Basque Country and Asturias, who, since the first day of the Spanish War, stood up in defense of the Republic and bravely defended their territory for a year. At that moment, I remembered the festive reception in Bilbao and compared it to this dramatic departure from Gijon. Tears came to my eyes. It’s a pity that there were no ships, so that those fighters and people could have evacuated and saved themselves from Franco’s terror. (One of my Spanish friends, who was with me as a wounded man in the hospital, did not manage to evacuate. He hid for more than a year in the mountains of Asturias, and then transferred to France and arrived at the Gurs camp. He then kept quiet about the great atrocities committed against the soldiers and the people). However, this was contributed to by the policy of the non-interference and the navies of Italy and Germany, which together with Franco, prevented access to ships for the Republic, or they sank them. Thinking thus about the fate of the people who remained, I firmly decided to return again and fight for the just cause of Asturias and the entire Spanish people.

We traveled like that for approximately two days and two nights. Everything worked well and we didn’t meet any enemy or other ships anywhere. However, on the third day, when we were about 40 miles from the coast, just as we entered the territorial waters of France, we were hit by a gale. Coal fuel is gone. The engine stopped working and we surrendered to the sea current. Luckily for us, a French fishing boat came across us. We signaled him to approach us, and then we explained our situation and asked them to tie us up and drag us to their shore. However, the French refused. That’s why we resorted to trickery. We told them that we had run out of water and food and asked them to at least give us something. They agreed and demanded that we send two or three others to their ship by boat. We hastily agreed to use weapons to force them to tie us up. Four of us went with hidden pistols in our pockets and machine guns in the boat. I had a gun and 3 bombs. When we boarded their ship, we again tried to convince them to tow us away, referring to maritime regulations, i.e. that ships and people in distress at sea must be helped. They didn’t want to agree this time either. Then we told them that we would use weapons if they didn’t do it. Seeing that we were armed and had no other way out, they tied us to their ship, even though we did not draw our weapons at all. We all transferred to their boat and requested that they transport us to the port of La Rochelle.

On the way to the port of La Rochelle, we managed to establish a more intimate contact with the crew of the French fishing boat, and especially with the owner, who caught the eye of our little boat. We promised to leave it for him. Since I spoke French quite well, I pressed this thought on him more and more. I convinced him that I could solve this matter for him with the Spanish consul in La Rochelle, if he would allow me not to fall into the hands of the French police, who would be waiting for us on the coast. I convinced him that I was Spanish and that it would not be difficult for me to do it. As proof, I showed him my party card in the name of Mariano Valdes. He believed me and promised that he would hide me in a fishing net, and in the evening take me off the ship and escort me to the consul. That’s what he did. All my friends knew about this, but no one revealed me to the French police.

When night fell, the owner of the ship brought a cape, which I immediately put on over my military uniform. Then we went to a tavern where he introduced me to the Spanish consul of the Republic, with whom he had previously arranged this meeting. My goal was to go to Spain again, through the Consul, to the south to join the International Brigades. He listened me, but when he saw that I was still in uniform, he whisked me off to a taxi and took me to the local KPF committee. There I handed over the guns and the bombs, and an official took me home. I rested a bit and we spent some time talking about the situation in the north of Spain, and he explained about the political situation in France. He was an attentive and pleasant interlocutor The next day I received from him a second-hand civilian suit from him so I went to the train station with his son. He has a ticket for me to Paris.

As soon as I arrived in Paris, I contacted my friend Robert at an address I already knew. I found him in his apartment in the hotel, “Excelsior”. I told him in detail my Spanish biography and my desire to return again. He then ordered me to rest well first and promised that I would probably be cross the Pyrenees in 14 days.

However, it was not even ten days, and I received an order from Labud Kusovac and Bora Baruh[iii] to go to the province of Ardennes. There, as a Spanish fighter, I was supposed to connect with our emigrants who were working to cut down the forest. I was to agitate amongst them for going to Spain. However, they forbade me to tell them about the collapse of the northern front. I was supposed to have introduced myself as a fighter from the south, who came to France on leave. Bora falsified my ID in the name of Ivan Poia.

I established the first contact with our emigrants in the village of Lunua, in the county of Charleville. In the tavern of that village, after a few days, I was arrested. The gendarmes asked for an identity card and when they looked at it, they told me that they were looking for me. Allegedly, they were informed that Ivan Poia had stolen a bicycle. I immediately understood that it was an Ustasha setup. The gendarmes took me outside, put me in the “marica” that was waiting and took me to the county prison Charleville. There they searched me and found a hidden party book in the name of Mariano Valdes.

After a three-month investigation, I was brought before the court where I was presented with documents confirming my true identity as Voislav Milošević. I was sentenced to 6 months in prison and lifelong exile from France, for falsifying personal documents and recruiting workers for Spain. The period spent under investigation is included in that sentence. I filed a complaint so I was transferred to Nancy, where the appeals court of the province of Ardennes confirmed the original sentence. I spent the rest of my time in prison in Nancy. After that, the police set a route for me to leave French territory.

Instead of leaving France, I went to Paris. I explained to my friends what had happened to me, so they made it possible for me to cross the Pyrenees with a group in April 1938 and to meet again in Spain. From Figueres, I went straight to the “Divisionario” battalion and stayed there until the end of the war.

Voislav MILOSEVIC

[i] This is likely Bora New who was in charge of recruiting students.

[ii] The memories of Vojislav Milošević, taken from the tape that are kept in the archives of the Association of Spanish Fighters, with subsequent consultations with him and the use of other material, were prepared for the press by Radovan Panić.

[iii] Possibly V.E. Gorev “Sancho” rmh.