Arthur Witt by Peter Arthur Witt and Bert Witt

Arthur Witt lived an interesting and full, but all too short, life. The first child of Herman and Ida Witkowsky, he was born on October 4, 1907, in Brooklyn, New York. The family changed its name to Witt in late 1916. He died February 27, 1937, fighting the Fascists on the battlefield at Jarama, Spain during the Spanish Civil War. [i]

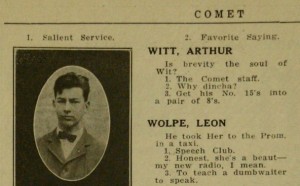

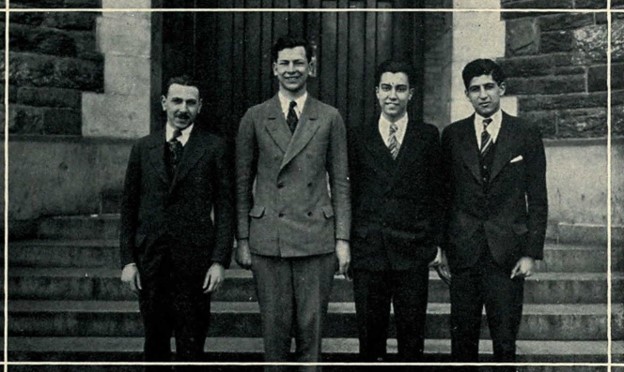

Arthur grew up in the Bensonhurst district of Brooklyn where he attended grammar school through the eighth grade. He then went on to New Utrecht High School, from which he graduated in 1923 at age 16. Lanky and handsome, Arthur at 6’2″ towered over most of his classmates. In his senior year, Arthur was the assistant editor for a semi-annual school publication, The Comet.[ii] He was also a member of the Arista Society, the school’s honor society.[iii]

Arthur grew up in the Bensonhurst district of Brooklyn where he attended grammar school through the eighth grade. He then went on to New Utrecht High School, from which he graduated in 1923 at age 16. Lanky and handsome, Arthur at 6’2″ towered over most of his classmates. In his senior year, Arthur was the assistant editor for a semi-annual school publication, The Comet.[ii] He was also a member of the Arista Society, the school’s honor society.[iii]

His graduation listing in the June 1923 yearbook indicated that his ambition was to “Get his No. 15s [shoe size] into a pair of 8s.” In the listing of class celebrities, he was called the Class Stretch, probably referring to his height. Another listing also noted that Arthur would begin his academic career in journalism at City College of New York (CCNY), but added “Lord knows where he will finish it.”[iv]

Arthur’s late teens coincided with “The Flapper Years” and the period known as “The Roaring Twenties.” In the euphoria after World War I, life seemed just a bowl of cherries to the young generation, while their elders speculated in rapidly-rising land, buildings and the stocks of corporations. Given to recklessness, Arthur and his friends in high school, and later at CCNY, balanced their hard studying with many a wild party at which cigarettes were plentiful and The Volstead Act (prohibiting consumption of alcoholic beverages) was ignored.[v]

Arthur enrolled at CCNY in September 1923. He became a member of the Associate Board of the student run publication, The Campus.[vi] According to his brother Bert, at the end of Arthur’s freshman year, he lost interest in CCNY, announcing a new and consuming interest in journalism. He applied for transfer and was accepted into the University of Missouri, where he enrolled in January for the Spring 1925 semester.[vii] [viii] The School of Journalism, in the shadow of Joseph Pulitzer, was highly regarded. On the other hand, Arthur’s mother was as devastated as if he were leaving for the jungles of Borneo. To her, Missouri and Borneo were equally foreign and probably equally dangerous. Arthur left for Missouri, refusing any more money than he had been allowed for the public college, CCNY, with a battered suitcase – only half-filled with clothes – and an extended thumb to hitch rides.[ix]

During the one semester Arthur spent at the University of Missouri, he wrote a series of letters and postcards to his parents. He listed American History, English Life and Letters, English Masterpieces, Geology, and Military Training as the classes he was taking.[x] According to his brother Bert, Arthur loved the Cavalry Unit of the Reserve Officer Training Corps (R.O.T.C.), as he had always loved horses and riding.

From Arthur’s letters to his parents, he got good grades (mostly Bs, 80-90s). He wrote home about his friends (a number of other students were from Brooklyn), his job (typesetting and printing the lunch and dinner menu for a local hotel/restaurant, for which he received three meals a day). He gave no hint in his letters that he was dissatisfied with school, although he did say that he thought that in general people learned more outside than in classes. [xi]

At the end of the term, Arthur wrote to his parents that the only real education was to be had at Harvard and that he had been studying during the final part of the term to take the entrance exams to get into Harvard. He also revealed that he had abandoned that idea as he found that he would not be able to prepare sufficiently to pass the exams. He also told them he would not be returning to Missouri in the fall, his plan being to return to CCNY.[xii]

Wanderings

On May 30, 1925, having finished his first semester at the University of Missouri, Arthur wrote his parents that he planned to hitchhike home to Brooklyn. The same day, he wrote his parents again from Columbia, MO telling them: “I’m on my way! Before you get this I’ll be out of Missouri and halfway thru Illinois.” He sent them another postcard on Sunday, May 31, from St. Louis saying:

Hit St. Louis last night at 5 p.m. Unexpectedly met a college friend with the phenomenal name of Al Sunshine who picked me up in his car and took us away to his city’s pride “The Municipal Open Air Opera,” a delightful light opera performance in a large bowl. Then to a sound sleep. Thus endeth the first day and begineth the second.

Later in the day, he wrote from Terre Haute, Indiana saying: “So far, not so bad. Breakfast in Missouri, dinner in Illinois, and supper in Indiana. 1,175 more miles to go. Having a keen time.”

By 11 p.m. that night, however, it appears that Art’s plan to return home had changed. He wrote his parents a letter, mailed the next day, saying that he had met up with four boys at a hotel — three of them were students at the Art Students League in New York, and the other, David Farber, had known him “vaguely” at CCNY–and would be traveling with them across the United States to Seattle.

David told Art that they had made a deal with a New York newspaper called the Graphic to do a bicycle trip from New York to the west coast. During the trip, they would “write Sunday Specials for those papers, pretending to be travelling on their own hook, broke.”[xiii]

David also told Art that because one of the four boys was leaving the group, Art could get his job. But, from reading Art’s account of the conversation, and Dave’s diary (Art seems to have come into possession of Dave’s Diary about the trip), the group had abandoned their bicycles and were now hitching across the country, getting rides in cars or freight trains, stopping at big cities to be photographed and to write their story. Dave indicated that their expenses were being paid by the newspapers.[xiv]

Dave’s diary indicated that he f left the east coast on May 18, by bicycle, with three companions: LaVerne Squires, Christopher (Chris) Graham, and Albert (Al) Darver. Their travels took them through cities in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Washington, D.C., and then West Virginia, Ohio, and Indiana. They had ditched their bicycles along the way due to faulty equipment, strenuous nature of riding the bikes, and dangers of being hit on the road, and continue the trip hitch hiking.[xv]

Dave’s June 1, 1925 diary entry was: “Catch Arty coming home from U of Mo. With friend Jules. Al & Chris don’t show up. LaVerne decides to travel alone. Art & I continue to Seattle.” Interestingly, there is only one more entry in Dave’s diary, dated June 2 – “Hit St. Louis on truck. 215 miles.” (Art begins to use the same diary book further on in the summer – by this time he has split up with Dave).

Art’s letters to his parents after he leaves St. Louis did not mention Dave by name again. However, in his letter home from Kansas City on June 12, he talked about extending “their” trip through the Angel City [Los Angeles] “from which we will travel up the Pacific coast north to Seattle.” There are then no additional letters until July 5, when Art is in Denver, seemingly without Dave. Art now appears to be traveling alone (or perhaps occasionally with people he meets along the way), until he heads back to New York in August.[xvi]

Besides the letters home about his summer adventures, Art also kept a journal beginning May 31, the date he left Columbia, supposedly to head home. The journal often contains materials not included in his letters; therefore, some of the journal entries are interspersed with the letters to provide more detail. It appears that Arthur filtered some of his experiences by not including them in his letters, perhaps to not cause worry to his parents.[xvii]

Arthur’s trip was plagued by a shortage of funds, inconsistent access to work, and a poor diet and unhealthful sleeping conditions, which produced rashes and illnesses. During his two months traveling to and around Colorado, Art sold kitchen gadgets at a County Fair in Colorado; barked programs and souvenirs at a Fourth of July Weekend Rodeo in Cheyenne, Wyoming; and tried to sell tourists bus trips to Pike’s Peak. He also worked as a fourth cook for the railroad, which meant he washed all the heavy pots and pans. In his journal Art described his frustrations and experiences after his first month of his trip west:

I’ve quit. I’m going home. Let the other boys travel around from China and Paris – I’m not big enough for that. Too many things have happened to me. I can’t hold them all. I’ve got to write them down or tell them to somebody or both. I can’t just go on having things happen to me.

It’s less than a month since I left college – what a month.

I’ve left one buddy for a second and finally dropped him too.

I made up my mind to travel around the world and I decided to go back home.

I went east to Terre Haute, Indiana, and came west to Denver. When I get well, I’ll be headed east again.

I’ve been a baker, a dishwasher, a harvest hand and a flunkey.

I’ve slept in jails, parks, fields, flophouses, gymnasiums, and hotels.

I’ve eaten at restaurants and lunched on a loaf of bread and a jar of jam.

I’ve been searched by police for concealed weapons.

I’ve dogged the streets of many a city looking and feeling like a bum.

I’ve seen sunrise and sunset in the Kansas flats.

I’ve slept at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

I’ve served dinner to seventy Mexicans.

I’ve been given hats by a Kansas City salesman and a travelling Mexican tattoo artist.

I’ve had my name in many newspapers as a hobo artist travelling round the world.

I’ve been given a dollar by Jimmy Costello, vaudeville equestrian.

I’ve been in Terre Haute, St. Louis, Kansas City, and Denver.

I’ve been in Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, and Colorado.

—Arthur Witt Journal, approximately June 20, 1925 (Arthur Witt letter collection).

Despite Art’s statement about coming home, he spent another month in Colorado, trying a variety of different jobs and schemes to make money. At several points, his parents sent him money to supplement what appear to be his meager earnings. On August 1, he got a car ride east, the beginning of his efforts to return home. He arrived home about August 10.[xix]

While it is not clear what Arthur did from September 1925 to March 1926, it does not appear he was enrolled at CCNY. On April 14, 1926, Arthur wrote his parents from Pittsburg that he was “busting loose again” to travel “west to the coast and beyond.”

Arthur’s 1926 travels took him back to Colorado, where he had spent part of the previous summer. Unfortunately, there are no letters or other information to document his travels between April 14, when he informs his parents he is headed west, and August 16, when writes them from Denver, Colorado. By September 20, Arthur is in San Francisco. His letters from there express interest in catching on as a seaman on a ship heading west. On September 23, he wrote that he had obtained a registration card to enable him to be employed as an ordinary seaman in the deck department of a ship. However, he also noted that there are many other individuals looking for work as well, so it could be awhile until he is given an assignment, most likely on a coastal line ship, not one headed to China. Meantime he notes that he will try to get a “landlubbers job.”

The next day Arthur wrote from Sausalito that he has gotten a job as a dishwasher on a ferry boat that traveled between Sausalito and San Francisco. By September 29, he had moved onto what he calls El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, which was the name of the Spanish pueblo founded in 1791, which became the modern-day Los Angeles. He is still hoping to catch on with a ship, maybe an oil tanker or a passenger ship to Honolulu.

His letters talk of Los Angeles as a boomtown, its rapid growth, and people hawking land deals. He also laments “the hundreds of young people that come here in search of their fortunes,” for whom “Los Angeles is the City of Broken Promises.”

On October 2, he wrote that he is not having luck “trying to get a ship to someplace. It’s a hard proposition, what with seamen’s unions and oriental labor and hipping boards and marine service bureaus. Nothing to do but wait for something to turn up.” On October 5, he was back in San Francisco saying that “All is well, I shall not write for 2 weeks.” And here the available letters end.

According to his brother Bert, Arthur “sailed back to New York as a seaman aboard a freighter through the Panama Canal. For eight hours every day Arthur, and the other novice seamen hung over the side of the lumbering ship, in calm water or rough, scraping the metal plates and painting the entire hull. He never saw the engine room or the bridge.”

After his western travels, Arthur was a changed man in almost every way. Perhaps most significantly, he had listened to the stories of countless lives; he had seen and experienced firsthand how most Americans had to earn their daily bread with their hands and backs and had precious little to show for it.[xx]

Arthur returned to his studies at CCNY in January 1927, and took classes until fall 1929 (verified by the Registrar’s Office at CCNY). He officially graduated in early 1930 with a Bachelor of Science in Social Science. [xxi]

Activism Replaces Wanderlust

When the 1929 Crash hit and the working people of America couldn’t even keep their poor-paying, un-unionized jobs, Arthur moved to Cleveland’s black ghetto, joining the staff of The Friendly Inn Settlement House and later The East End Neighborhood Settlement. [xxii] These well-established settlement houses, galvanized by The Great Depression, became centers of community organization and agitation for food for the hungry, against eviction of those who couldn’t afford rent, and equal job opportunities for blacks (“last to be hired, first to be fired”).

Arthur Falls in Love

Attending a regional conference of community activists in Chicago around December 1929, he met Ruth Cizon, a social worker from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. [xxiii] Ruth was born in Russia on November 25, 1907, and immigrated to the United States via Canada in 1921. Ruth received her bachelor’s degree in social work from the University of Wisconsin.[xxiv] For a few months, Arthur “bummed” to Milwaukee every time he could get a few days off, traveling all night both ways if necessary, to spend a few hours with Ruth.[xxv]

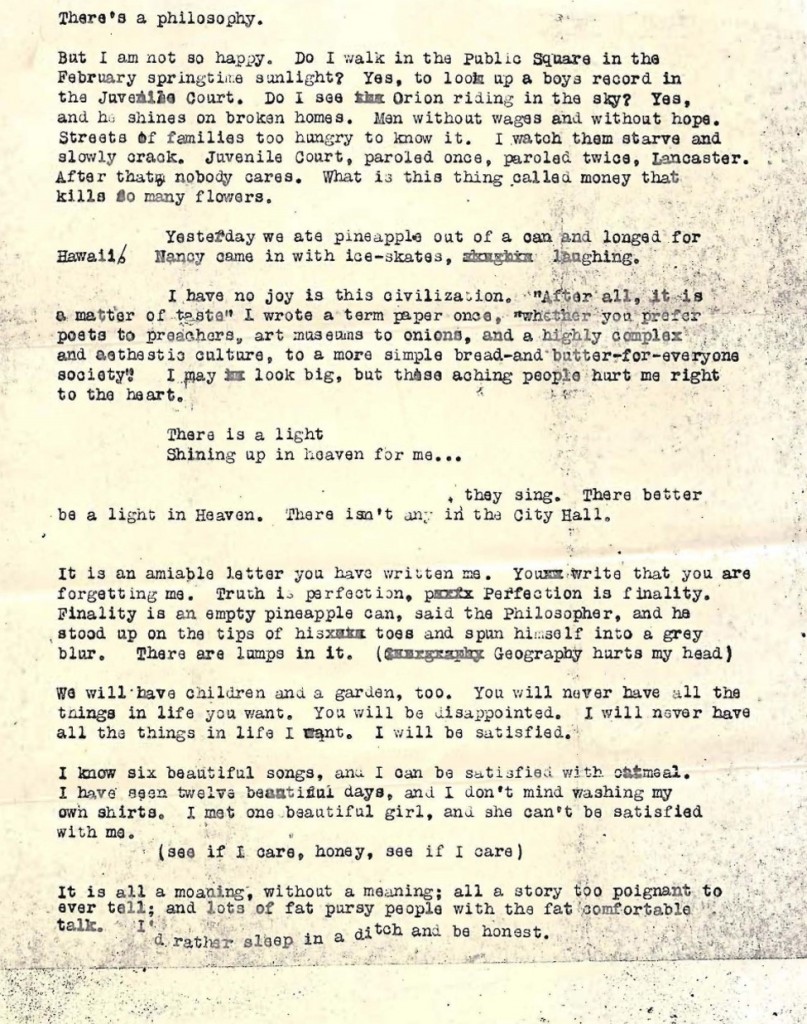

Letters from Arthur to Ruth (First one appears to have a first page missing). They were written before they were married (1930).

Arthur and Ruth were married on March 17, 1930, in Cleveland, Ohio.[xxvi] Apparently, Arthur had not told his parents about Ruth. On March 19, 1930, he wrote his mother and father to announce his marriage and introduce them to Ruth.

Here is a little item of news for which I am afraid you will be unprepared, although it is by its nature an event over which, if you love me, you will be happy. I have not been writing you about a little girl in whom I have been very much interested ever since she came to Cleveland (last December), but there is such a one. I think you will be inclined to believe me, we have fallen in love not only with speed, but with intelligence, honesty, and permanence. Now if you are not too surprised, I will tell you the story of how we got married.

The letter goes onto describe a wedding celebration that took place at the settlement house.[xxvii] An announcement about the wedding and celebration appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on March 23, 1930.[xxviii]

The letter goes onto describe a wedding celebration that took place at the settlement house.[xxvii] An announcement about the wedding and celebration appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer on March 23, 1930.[xxviii]

After they were married, Arthur continued to work at one of the Settlement Houses in Cleveland and, at least initially, Ruth worked for the Associated Charities. Arthur also was taking graduate classes at what is now CASE Western University in the School of Applied Social Sciences (Spring 1930 to Spring 1931 semesters).[xxix]

At some point after they were married, Ruth moved to back to Milwaukee, her hometown (probably for work reasons), with Art continuing to work in Cleveland. During their time apart, Arthur wrote Ruth letters with news of the day, but sometimes he just poured out his love.

Honey chile:

I love you. I love you more than tulips and the smell of fresh mown grass in the summer time. My love for you is like eating strawberries underneath a tree by the Art Museum; it is like swimming at night by lantern light. I have been to New York and I have been to Jersey, yea, I have been stalled at midnight on the mountains in Pennsylvania, but the image of you eraseth itself not from my heart. By a motor truck I romp the streets, yes, even with a rundown battery I careen by woodland and central, to take the young men and the boys swimming, but all the while I think of you. The drum beats every night where I walk the boards of stagery, and Emperor Jones fires blank pistol shots at me, but I wish you were here.

My girl is like the taste of rain running the face’ like snow melting down the side of a mountain. She is far away but I am not alone. She writes to me and I am comforted. Kisses she sends me by words and sentences caress me. Soon she will come and we will eat spumoni together. On the edges of roofs we will sit and I will bit her ear for joy. She will sing again, the songs of the Cossack lover.[xxx]

In summer 1931, Arthur wrote a letter to Ruth describing a visit from his 15-year-old brother, Bert, who with a friend had hitchhiked to Ohio to surprise Arthur. Arthur was working at Hikiwan camp at the time.

Merrily merrily they hitched from New York, with blankets and a pup tent on their backs, and right this minute Bert is flopped in that little tent, just around the corner from mine, reading All Quiet on the Western Front. And he can stay about 4 more days, and still get back in time to start school. The campers are just his age, and he is having a ripping time.[xxxi]

At some point, prior to 1933, both Art and Ruth moved to Chicago.

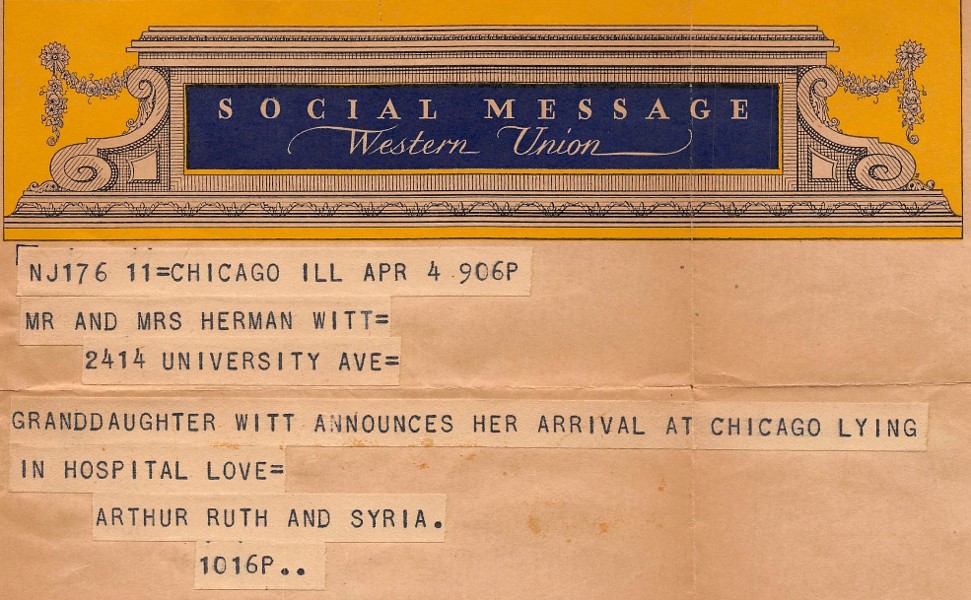

On April 1, 1933, Arthur and Ruth’s daughter, Syria Nina Witt was born.[xxxii] Although birth and death records indicate that Syria was born on April 1, it is not until April 4, that Arthur and Ruth send Arthur’s parents a telegram announcing her birth.

After Syria was home from the hospital, Arthur wrote his parents about Syria’s birth, saying:

The newest Witt is now home from the hospital and laughing at my attempts to pin a diaper. A girl, Syria Cizon Witt, by name, with a big head and a slim body, green eyes, put-nose, lies in a crib in a room devoted solely to scales, bath-tables and flannel kimonos. Sometimes she lies with her eyes open reminiscing on her past, but mostly she eats and sleeps. The other Witt, newly slim and glorifying again in fitting into last year’s spring clothes, also eats and sleeps, and spends some time directing the activities of Olivia Champion, baby-caretaker and pastry cook.[xxxiii]

In Chicago, Arthur organized teams of neighbors to move the furniture of evicted families back into their apartments. He visited steel mill workers in Chicago and Gary arguing the need for unionization and led delegations from the Unemployed Councils to City Hall demanding food allowances for starving families.[xxxiv]

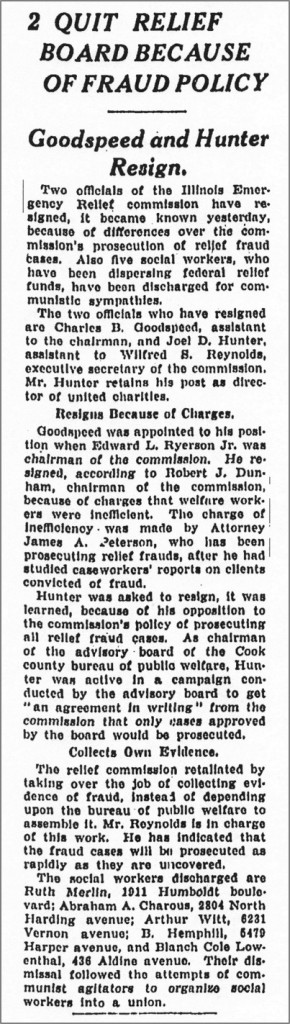

In 1933, while working as a social worker for the Illinois Relief Commission, Arthur was fired along with four other social workers who were thought to be communist agitators. They were accused of attempting to organize social workers into a union. An article in the Chicago Daily Tribune documented the story.[xxxv]

In his autobiography, Bert described visiting Art sometime after Syria’s birth:

He was what today we would call a “community activist,” but in those days was loosely called a ‘communist agitator.’ When we weren’t helping neighbors carry some unemployed family’s furniture back into the apartment from which they had been evicted for non-payment of rent, he was leading delegations of unemployed to the City Council or somewhere demanding that governments become “the employer of last resort.”

One day, Art explained that at the steel mills in Gary, Indiana, on the edge of Chicago, the few workers still employed were being forced, almost every week, to accept a few cents less per hour. Those who objected were fired, because every morning thousands of men were lined up at the factory gates ready and willing to work for anything the company would pay them. Some of the workers were organizing a union, hoping that if everyone stuck together maybe they could get a decent wage, a living wage, even if they had to lay off every fourth week so other former employees could get some work too.

If the companies knew who the union members were, they’d fire them. There was no law to protect labor’s rights. So people from outside the steel industry were volunteering to distribute leaflets and make visits to workers’ homes. Was I game for that? I was. I wondered why he bothered to ask me.[xxxvi]

In 1936, for two semesters, Arthur took classes towards a master’s degree in social work from the University of Chicago. After Syria’s birth, Ruth worked for the Chicago Board of Social Services. [xxxvii]

The joy Arthur felt at the birth of his daughter was tempered by his vision of her growing up into a system, that in “good” times provided little more than subsistence to its workers and in “bad” times threw them on the scrap heap without a second thought. He wanted a fundamental change in the system, but he felt that the greater the freedom to speak, to organize, to act – the greater the chances of change. In a November, 1936 letter to his mother, Arthur wrote about how he and others had worked to put Roosevelt into office, but also their disappointment with Roosevelt and his policies.

Now the mass of American people put Roosevelt in office to represent them for better living conditions, and we want to see results. The American Liberty League puts pressure on Roosevelt to cut wages and cut relief and fire Tugwell. That is why I am out of work, that is why Edith’s job is shaky, that is why Ruth’s job is shaky, and that is why RELIEF IS BEING CUT, and WP [probably WPA]. That is why a little boy died of rabies dog bites because his mother didn’t have $18.50 to pay the clinic and their funds were too low.

So, we have to put pressure on Roosevelt, too. If we expect progressive legislation, we have to organize a bloc of fighting Congressman that will introduce these measures. We have to send delegations of the trade union leaders that elected Roosevelt down to the white house to demand that he carry out his election promises.

And we certainly have to put pressure on Roosevelt in the most impressive way of all, the organization of a Labor Party that can put into effect Democracy and a better deal to the workers WITH OR WITHOUT ROOSEVELT. Watch and see how La Guardia will loosen up, for instance, when he will see that he either comes out for the American Labor Party AND ITS PROGRAM, or else they will be strong enough to pick a man that will.

Roosevelt for millions of Americans is a symbol of progress; but unfortunately, RELIANCE upon Roosevelt will not bring that progress. We have to put our shoulders to wheel and build up a real People’s Movement, to pick the politicians of the people’s politics.

Arthur ended his letter by asking: “Who has been reading The Olive Field? All about Spain.[xxxviii]

Arthur also showed concern when a cabal of Army generals led a rebellion in July 1936, against the Second Spanish Republican and the fascist leaders of Germany and Italy began to pour military aid into the efforts of General Franco to overthrow that government. He did not hesitate long to think about going to Spain to join the growing number of international troops that were joining with the Republicans to fight fascist General Franco’s Nationalists.[xxxix]

Arthur was among the very first Americans to form a secret network recruiting and arranging for young men to violate President Roosevelt’s policy of “neutrality” by crossing the Atlantic Ocean to France, with the intent of supporting the Spanish Republican (Loyalist) Army. Having worked to encourage others to volunteer, Arthur soon became a volunteer himself. Once in France, the volunteers moved to the south of France and crossed into Spain. On February 20, 1937, the French socialist government of Premier Blum closed the border forcing volunteers to covertly cross into Spain by foot over the Pyrenees mountains. Arthur and his group were hurried across France and crossed the border by bus in order to get into Spain before the border was closed.[xl]

The Flag of the Lincoln Battalion

When Arthur met his younger brother Bert in New York in 1937, to tell him he was about to leave for Spain, Bert was devastated. Arthur, nine years his senior, was a model, and in many ways a substitute father to him. Moreover, Bert loved Arthur’s wife, Ruth, and the baby Syria. Also, Bert had his own militant agenda and had already volunteered to go to Spain with his college classmate and buddy Paul Siegel, and was awaiting a decision as to his “qualifications” by the underground network.[xli]

Bert and Arthur both knew, that only one son per family would be accepted. Arthur argued that Bert, who was more or less living at home, needed to stay with their mother, who was still recovering from the untimely death of their father in 1933. Bert argued that Arthur, being older and more experienced, was more valuable to society and besides Arthur had a wife and baby to consider. They agreed to meet again the next day to talk further.

That night, January 28, 1937, Arthur sailed aboard the Aquitania for France, and then proceeded overland to Spain with other Illinois volunteers.[xlii] Inside his shirt was sewn a banner which read “Abraham Lincoln Battalion.” His group was one of the first contingents of Americans to join the Spanish Civil War as part of the XV BDE, Lincoln BN.[xliii]

In another account, Arthur’s sister, Edith, described how Arthur arrived New York and told her he was off to Spain to fight the fascists.

One day my older brother Art appeared from Chicago. We walked the streets, talking. He said, “I want to tell you something but you can’t tell anyone else, not even your friends, not even your room-mate. I’m on my way to Spain to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade.” Oh, how thrilling that was. How romantic we were. How I envied him. It was always like that. He was older. He was a man. He could do things I couldn’t do. “If you have any money you can spare, I’d appreciate it,” he said. “I have a little shopping to do. I reached into my purse. I had twelve dollars. I gave them to him. “That’s great, he said, “I can buy a pair of boots. By the way, there are a few other fellows with me. Could you get some of your friends over tonight and have a party?” We had spaghetti with meat sauce, French bread and salad and red wine, our special deluxe gourmet haute cuisine during the depression. It was the last time I saw him.”[xliv]

Before leaving New York, Arthur wrote a note to Ruth: “For yourself, love and kisses. I am delighted to be in the company of my brother and sister, who remind me of you…Art”[xlv]

Art wrote Ruth several letters in February from Spain.

Dear Ruth:

I am writing after the first drops of rain in 8 days. It is not the rainy season now, and rain was unexpected. We did not be wet, however. You should see the Spanish kids in the villages. The roar around like the kids in Cleveland. I gathered them in a ring the other days and they started to play Spanish ring-around the rosie.

I am in splendid health, actually gaining weight, working hard.

I have not received any mail from you. You may write to me c/o Lincoln Battalion, Int. Col. c/o Socorro Royo Albacete, Spain. Delighted to receive cigarettes, chocolate, and socks. Can’t use money. Oscar and Oliver are well.[xlvi]

Art

——————————

Dear Ruth:

I am writing in the center of an admiring circle of young Spaniards, who think the Americans are the last word in technique.

It is essential that we attempt to correct the policy of our government to enable shipment of materials. And further essential to send more healthy men, with or without experience. Needed are chauffeurs, truck drivers, hospital men, etc. Send them.

Art

The battle to defend Madrid had raged for months. The front lines were some miles to the east and north of the city. The newly formed Abraham Lincoln Battalion arrived in the Jarama area on February 14. They were under the command of Robert Hale Merriman. The newly-arrived volunteers were thrown into battle on February 23, 1937, and again on February 27, 1937, in futile assaults against entrenched Nationalist forces on Pingarrón Height.

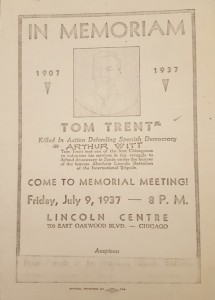

The Lincoln volunteers had little training and their equipment was no match for the forces they faced. The attack on February 27 was especially costly. Advancing in a suicidal attack without artillery, armor, or flank support they lost approximately 120 dead and 175 wounded, or 66% casualties. [xlvii] According to information received by Bert Witt, Arthur Witt rose from his trench to run back and bring machine-gun ammunition to his pinned-down company. He made it to the ammunition dump and almost back. [xlviii] Arthur’s war lasted only a few days. The family learned of his death in the summer of 1937.[xlix] On July 9, 1937, the Illinois Friends of the Lincoln Battalion held a memorial meeting for Tom Trent (Arthur Witt) in Chicago.[l]

In the late 1970s, as the 50th anniversary of the Lincoln Battalion approached, CCNY agreed to post a memorial plaque and create a scholarship to honor its students and alumni who died in Spain. Funds were raised privately under the chairmanship of CCNY graduate Dr. Irving Adler of Dartmouth University. Edith, Bert and Ellen Witt were major contributors to the Volunteers-in-Spain scholarship endowment and the memorial plaque, which lists Arthur’s name among a dozen others. The plaque was installed April 13, 1980, and is currently located on the second floor of the North Academic Center (Convent Avenue) on the campus.[li]

There are those who claim that the Civil War in Spain was the first major battle of World War II, that the Lincoln Brigaders were “pre-mature anti-fascists” and therefore played a significant role in alerting America to the need to stop Hitler and Mussolini before the fascists conquered the world. Others claim that the Lincoln Brigaders were cynically used as martyrs by the communist and left-wing international groups to create sympathy for the Republican Government of Spain and embarrass the “neutrality” policy of the U.S.A. Of the 2,800 Americans who volunteered before the Franco-Hitler-Mussolini fascists finally conquered Spain, 670 were killed in battle and 1,000 received battle wounds from minor to loss of one or more limbs. The sacrifice of the American Lincoln Battalion is almost unprecedented in the history of volunteerism.[lii]

Ruth and Syreia After Arthur’s Death

Arthur’s death affected many people’s lives. Ruth and Syria were left without husband and a father. However, life moved on for both of them. After Arthur died, Ruth completed a master’s degree and continued her work as a social worker. In 1941, Ruth married Don Murray in New York. They had a daughter, Gayle Murray. They would eventually move to Los Angeles, then in the early 1970s to Mendocino, California. According to an article in the Mendocino Beacon after her death, Ruth was known by her friends and the community for her work for human rights and justice. When Ruth and Don Murray moved to Mendocino, he continued his active life in theater and Ruth began her work with community organizations. She was an active member of Gray Panthers, a founding member of Health Watch, a member of a county task force to determine the future of the Coast Clinic and a founding member of the board of directors of Mendocino Coast Clinics, Inc. The other members knew her as the conscience of the board for when discussions turned to matters of policy and finance, Ruth was always there to remind them of their primary mission to provide health services for those with the greatest need and the least access to care. She was an ardent supporter of the Mendocino Children’s Fund. She was counselor and friend to many people in the community, old and young.[liii]

Syria, who preferred to go by Syreia, had a career as a dancer. She lived New York, then Los Angeles, and finally in San Francisco. Family relationships were difficult for her, despite the efforts of extended family, like Arthur’s brother and sister’s, efforts to reach out to her. Reports from Ruth’s family indicate that relationships with Ruth were strained.[liv]

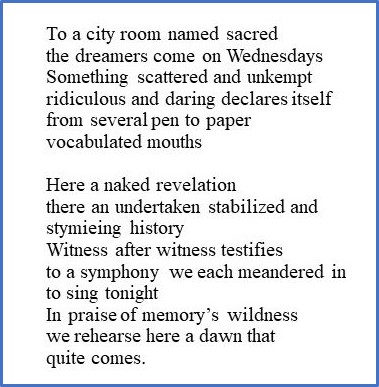

Syreia was married to William Eicker in 1960, but little is known about that relationship or how long it lasted. In her later years, she wrote poetry.[lv] Syreia died in San Francisco on October 11, 2006. Gayle Murray’s son, Ruth and Don’s grandson, Jerry and his wife, Linnea, helped clean out Syreia’s apartment and attended a poetry reading held in Syriea’s honor. One of the poems composed to celebrate her life by Wendy L. Wolters is included below.

ENDNOTES

[i] Portions of this biography were written in the 1980s by Bert Witt, Arthur’s brother. Peter Arthur Witt, Arthur’s nephew, subsequently expanded the biography with additional materials based on letters and historical documents to enrich Bert’s account. Peter also collected pictures and historical documents featured in this article. He also cross-referenced material within Bert’s manuscript with material from the autobiographies of Arthur’s siblings, Edith and Bert. Certificate and Record of Birth – Certificate 31773, City of New York, Department of Health, Note: all descendants in Witkowsky family were named Witt after January 1, 2016. All census records after that date show the family name as Witt.

[ii] The Comet, Volume 10(2), June, 1923, p. 2. Arthur was listed as the assistant editor beginning in June 1923 issue.

[iii] Brooklyn Daily Eagle, New Utrecht Awards letters, January 22, 1923, p. 23. Arthur’s induction into the Senate, the upper house of the Arista Society was listed in the article.

[iv] The Comet, June 1923, pp. 21 & 38.

[v] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 81. Unpublished.

[vi] The Campus, Microcosm Yearbook, CCNY, 1924, p. 155. He is listed as a member of the Campus Associate Board staff.

[vii] According to one of Arthur’s February 3, 1925 letter to his parents (Arthur Witt letter collection), he completed 23 credits at CCNY. It is not clear whether this was over the 1923-24 academic year right after he graduated high school, or spread out over the fall 1923, spring 1924, and fall 1924 semesters.

[viii] Letters Arthur wrote home during 1925, 1926 and the 1930s have been preserved. They were initially kept by his parents, and preserved by his mother, Ida. When Ida died, the letters appear to have passed to Arthur’s brother, Bert. (Bert’s notes about the letters, in his adult handwriting, can be seen on some of the letters). At some point, Bert passed the letters onto Arthur’s daughter, Syreia, and when she died, the letters were kept by Jerry Murray, a member of Syreia’s mother’s family. Finally, in 2018, the letters were passed onto to Peter Witt, Arthur’s nephew.

[ix] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. Unpublished.

[x] Military training was required of all male students at the University of Missouri when Witt attended.

[xi] Arthur Witt. April 6, 1925 letter to parents (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xii] Arthur Witt. June 7, 1925 letter to parents (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xiii] Arthur Witt. May 31, 1925 letter to parents (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xiv] Arthur Witt. May 31, 1925 letter to parents (Arthur Witt letter collection). David Farber Diary (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xv] David Farber Diary (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xvi] Arthur Witt. n.d. Letter to parents (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xvii] Arthur maintained a journal from May 30 to August 1, 1925. Entries were sporadic, with some of the information used to write letters to his parents during this same time period (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xviii] Arthur Witt Journal, approximately June 20, 1925 (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xix] Arthur Witt Journal, August 1925 (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xx] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 82. Unpublished.

[xxi] CCNY email to P. Witt, May 16, 2018. There is a little bit of confusion here, as Arthur still seemed to be traveling well into the fall 1926 semester.

[xxii] The Friendly Inn Social Settlement was established in 1874. It is still operating in Cleveland, Ohio. The East End Neighborhood House was established in 1907. It also is still operating in Cleveland.

[xxiii] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 82. Unpublished.

[xxiv] Ruth Cizon was born in 1908 in Russia to Israel Cizon and Sophie Kahn. Ruth Murray Obituary. Mendocino Beacon, July 1, 1999, p. 6.

[xxv] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 82. Unpublished.

[xxvi] Witt-Cizon. Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 23, 1930, p. 4.

[xxvii] Arthur Witt. Letter to parents, March 19, 1930 (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xxviii] Witt-Cizon. Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 23, 1930, p 4.

[xxix] Email from Office of the Registrar, Case Western University, July 15, 2018.

[xxx] Arthur Witt. Letter to Ruth. 1929 or 1930 before married (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xxxi] Arthur Witt. Letter to Ruth. Summer, 1931. (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xxxii] Over her life, Syria spelled her name in several different ways, including Syree, which Arthur used, and Syreia, which Syreia herself used later in her life.

[xxxiii] Arthur Witt. Letter to parents. April 1933 (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xxxiv] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. Pp. 82-83. Unpublished.

[xxxv] 2 Quit Relief Board Because of Fraud Policy. Daily Tribune, November 26, 1933, p. 23.

[xxxvi] Mervin Herbert Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 112. Unpublished.

[xxxvii] According the Registrar’s Office at the University of Chicago, Arthur attended the Social Sciences Division at the University of Chicago as a graduate student from January 2, 1936 to March 17, 1936 and October 1, 1936 to December 18, 1936. He did not receive a degree. Ruth’s job noted in Bert Witt. The Witt Family History, 1990. p. 206. Unpublished.

[xxxviii] Arthur Witt. Letter to mother. November 27, 1936. Ralph Bates, The Olive Field, (New York: E. P. Duttton, 1936) is about olive workers in southern Spain. Bates was born in Swindon, England in 1899. After serving in WW I, he began to travel, to France and then, in 1923, to Spain, where he had wanted to visit since boyhood (his great-grandfather, a steamer captain, was buried in Cadiz). He stayed in the country permanently from then on, traveling and doing odd jobs. He published his first work, Sierra, a collection of short stories, in 1933; in 1934, a novel, Lean Men. When the Spanish Civil War began in 1936, Bates enlisted with the government forces and made rank of political commissar. He helped to organize the International Brigade. Later that year he traveled to the United States to raise awareness of the plight of the Spanish Republic. The Olive Field book received good critical notices in the United States. For such writing, Bates has been hailed as a master of the “proletarian novel.” He was also the first editor for the International Brigade’s English language newspaper, The Volunteer for Liberty.

[xxxix] The Spanish Civil War was both a proxy war and a dress rehearsal that heralded the greater conflict (WWII) to come. The war pitted working class revolutionaries against traditional elites, democrats against Fascists, and Stalinists against Fascists. It was also a military training-ground. Tanks were tested and found wanting. Aircraft practiced the bombing of cities. Italian conscripts proved unwilling combatants, but German Nazis displayed their ruthlessness. Russia supplied weapons, tanks and aircraft in support of the Republicans, Germany and Italy did the same for the Nationalists. WWII started only six months after the final victory in Spain by Franco’s forces. (Bert Witt. The Witt Family History, 1990. p. 206. Unpublished).

[xl] The Roosevelt administration advanced a series of neutrality acts in 1935, 1936 and 1937. These acts imposed a general embargo on trading arms and war materials with all parties in a war. The 1936 act extended the provisions of the 1935 act for an additional 14 months. The 1937 act extended the provisions of the 1935 act indefinitely and extended the embargo to civil wars as well. In Europe, a non-intervention treaty was passed and as a result the French closed their frontier to volunteers. The information about Arthur being a recruiter comes from Bert Witt. The Witt Family History, 1990. p. 206. Unpublished.

[xli] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. P. 83. Unpublished.

[xlii] Sail List, Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Office, undated. Two lists one alphabetized and the second by ship and sailing date collectively referred to as the Sail List. The compiler is unknown but likely drew from 852.2221 records in the United States State Department Archives. The State Department obtained lists of 3rd class passengers from all lines travelling to Spain throughout 1937 and into early 1938.

Other Chicago Volunteers aboard the Aquitania include:

[xliii] Arthur Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 83. Unpublished. Hearings Before the Subcommittee to Investigate the Administration of the Internal Security Act and Other Internal Security Laws of the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate, Eighty-fifth Congress, First Session, on Scope of Soviet Activity in the United States, February 20, 1957, Appendix I, Part 23A, (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1957), A65. Entry reads Witt, Arthur, 31 years-old, passport #4724 Chicago Series issued January 6, 1937, which listed his address as 3830 Lake Park Avenue, Chicago, IL; and Leadville, Ohio. Records in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives indicate that Arthur Witt also used the name Tom Trent. Tom Trent was likely an alias used to protect his family while he worked for the Communist Party.

In The Abraham Lincoln Brigade, (Arthur Landis, 1967, NY: The Citadel Press), a carefully researched, well documented account of the Lincoln Brigade’s involvement in the Spanish Civil War he notes that some of the American group joined the XV Brigade on February 16th, but they did not see their first action until a few days later. Others joined only on February 26 and 27 in time for the decisive battle where Arthur was killed. Given when Arthur left New York, it is likely that he only arrived at the Jarama Front on February 26.

[xliv] Edith Witt, in The Witt Family: A Written History by Bert Witt, 1990. p. 92.

[xlv] Arthur Witt, letter to Ruth Witt, January, 1937. (Arthur Witt letter collection).

[xlvi] The two volunteers Oscar and Oliver noted in the letter are likely Oscar Hunter and Oliver Law.

[xlvii] A dramatic account of the battle was published in 2016 in The Volunteer, a publication of the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade: Jarama Series: Suicide Hill and the First Attack; Jarama Series: Pingarron; and Jarama Series: The Aftermath.

[xlviii] Bert Witt. The Witt Family History, 1990. pp. 206.

[xlix] Haywood, Harry, A Black Communist in the Freedom Struggle: The Life of Harry Haywood. Minneapolis: University Minnesota Press), 2012, 235. Haywood mentions Arthur’s death stating “Captain Merriman was wounded, as was my old friend and schoolmate at the Lenin School the Englishman Springhall, known to all as “Spring,” who was an assistant to the brigade commissar and along with Merriman had led the assault. My good friend from Hyde Park, our YCL organizer, Tom Trent, was also killed that day.”

[l] Peter Glazer. Radical Nostalgia: Spanish Civil War Commemoration in America. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2005), 61. An announcement for the gathering was found in a file labeled Arthur Witt in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade collection at the Tamiment Library at New York University.

[li] Peter Witt and Joyce Nies visited CCNY on May 20, 2016 and took the picture of the plaque.

[lii] Adolph Ross, Americans in the Spanish Civil War, n.d. (Seattle: Self-published).

[liii] Mendicino Beacon,Obituaries, Ruth Murray, July 1, 1999, 6.

[liv] Personal communication with Jerry Murray. 2017.

[lv] Syreia’s poems obtained from members of Syreia’s San Francisco poetry community.

To Peter Witt:

I read your accounts about Arthur Witt and Ruth Cizon with great interest. Ruth was my great-aunt. I am the granddaughter of her sister, Toby Cizon Katz. Sadly, I only met Ruth once, when I was about 12 years old. It is wonderful to learn about her from your family archives.

Best Regards,

Judith