Los Rompedores – by Ed Lending

Editor’s note: At the initiative of ALBA board member Chris Brooks, who maintains the online biographical database of US volunteers in Spain, the ALBA blog will be regularly posting interesting articles from historical issues of The Volunteer, annotated by Chris.Over the next three months, Blast from the Past postings will showcase articles about the American volunteers who served in the Artillery. Many of these articles ran in The Volunteer during Ben Iceland’s tenure as editor. Iceland, who served in the Artillery, recruited several of his fellow artillerymen to document their experiences. Iceland also shared his own experiences in a series of articles he originally wrote in the early 1940s. Together these articles shine a light on some lesser known American volunteers.

Los Rompedores

Ed Lending

[Originally published in The Volunteer, Volume 7, No. 2, July 1985.]

Teruel had been flattened. The Armies of the Republic were in full retreat. Our Dimitrov Anti-Aircraft Battery – a German IB unit – was wounded but firing.

The succeeding months became a blur of bombings. And of position changes, back – ever back – towards the Mediterranean. In the press, now, retreats were “rectifications of our lines to the rear.”

We HAD brought down a couple of Hitler’s bombers, thanks to our commanders’ artillery skill; our ammunition was not calculated to be that effective. Our 76.5mm guns were fed old-fashioned ammo, requiring direct hits to bring anything out of the sky. The bull’s eyes were rare.

It often seemed that our main mission was to give away our lightly camouflaged positions. We kept tipping our hand in a cat-and-mouse performance, enacted most mornings by the Luftwaffe and us. Whenever the daybreak dawned clear, its bombers came growling through the heavens. We would let the first fly past, unmolested. When within range, we’d open up on the next.

Inevitably, some squadrons veered, got us in their sights and, promptly, opened their bays… While we licked our wounds, and dreamed of “rompedores,” the remaining invaders (they seemed to go on forever) soared on to fry preferred fish.

Rompedores – the enemy ack-ack firing nothing else. They were the very latest, super explosive projectiles. Each detonated shell threw up an impassable curtain of lethal lead. A well-aimed shot would burst right in front of a plane’s nose, assuring its rendezvous with Hell.

For weeks, now, Headquarters had been promising us supplies of this demonstrably potent ordnance. We hungered for them – the better to defend ourselves, and the troops whose protection was our mission. But time elapsed and hope eroded…

Until that more momentous day. It started out typically. The sun showed itself, and the Luftwaffe’s sullen rumble suddenly filled the sky. We scurried to our posts. Our three surviving cannon assumed their parallel plane-tracking stance. Altitude and distance were calculated, fuses set, shell shoved into their breeches, lanyards tugged. The Condor Legion, predictably, responded. Bombs came shrieking down at us. The ground exploded in flame, bounced, and the world turned black – while we frantically pressed quivering bodies into Mother Earth.

Then, quiet – punctuated by the pleas of the wounded, and the abrupt order to move. SCHNELL. Our flanks had given way. Before this day was over, we would break records for the number of positions we were obliged to set up and abandon.

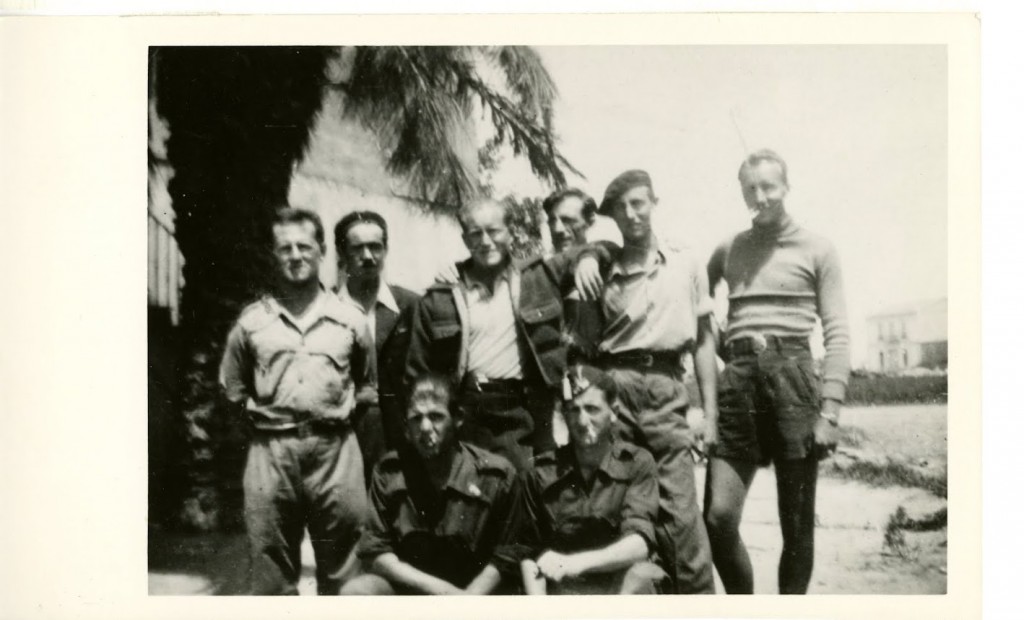

Yanks in the Dimitrov Battery, standing Sam Slipyan, Conlon Nancarrow, Ed Lending, Charles Simpson (?), Delmer Berg, Norman Schmidt, kneeling two Spanish Chauffers.

Each new position involved toil. First, it demanded digging our gun emplacements, with picks overmatched by the hard, rocky, almost impenetrable surface of these unyielding Aragon mountains. Then we’d muscle cannon into emplacements, stabilize them, and prepare for firing. Next, we unloaded the sinew-straining cases of ammo, which got heavier with each move. And finally, we scratched out our personal fox holes – they were often pathetically shallow – and made ourselves at home, sort of.

We were catapulted into the day’s last retreat by our observer’s alarm: “Enemy tanks – heading our way.” Routine turned into near pandemonium. We raced through the truck loading chores, abandoning everything not absolutely essential – and some things that were. We barely broke through the trap encircling us.

As twilight’s shadows were lengthening, we crossed the Ebro, at Gandesa. We were ground down, physically and emotionally. Our trucks’ conditioned matched their dispirited human cargo’s. They coughed, strained and chugged up a winding mountain road to our last position of this numbing day – where depression turned to elation. There they were, cases upon cases of rompedores! Hallelujah!

We leaped from the trucks, adrenaline surging. Everybody who could be useful pitched in to get the designated testing gun emplaced and action-ready. In no time at all, it was. Its crew took over; the rest of us cleared away. The Sergeant’s voice rang out – with unmistakable eagerness – in the German for “Gun No. 2 – Ready to Fire.”

A shell was slammed home, the lanyard yanked, and in an ear-splitting explosion the cannon blew up. Heads, arms, legs, and less definable parts of our comrades whizzed across the landscape…

No voice spoke. No eyes met. We were utterly alone, each of us, deep within darkest despair.

The silence was broken by Hans – broad-shouldered, horny-handed, reliable Hans. He arose, grabbed a pick and, with a muttered “Work is the only medicine,” started digging. No one helped.

As darkness took over, we drifted into sleep, oblivious to the stoniness of the bed beneath us. At midnight, we were awakened ordered to fall in with loaded rifles. Our Battery Commander, Albert (whatever his surname and formal rank, I never knew them), intoned a short, apt moving eulogy. Its end was punctuated by salvos from our rifles, shredding the velvety night. And stillness.

A brooding stand of pine trees scented the air. The knoll was bathed in the soft luminous light of a full moon. And then under its indifferent eye, the Dimitrovs raised their voices into chants of the German revolutionary standards: The Thaelman Brigade … Forward, We’ve Not Forgotten … The Peat Bog Soldiers … Hans Beimler, Commissar …. Auf, Auf – Tsoom Kampf (Up, Up – To Battle). Lastly, the measured rhythms of Lenin’s Funeral March.

It was stirring. The Germans were powerful singers, their voices lusty and resonant. The moment was hallowed…

Then our Political Commissar came up. His opening remarks were dusty, overworked bromides. Gradually he warmed to his mission, soon was thundering the guilt of those perfidious Trotskyites who had perpetrated this heinous act of sabotage. He vowed our vengeance and our eternal vigilance.

The spell was broken.