Fanny, Queen of the Machine Gun

Fanny Schoonheyt in Barcelona, May 1937. Photo by Agustí Centelles. Spain, Ministry of Culture, Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica, Archivo Centelles.

Fanny Schoonheyt, born in Rotterdam in 1912, was the only woman among the contingent of Dutch volunteers to take up arms in defense of the Spanish Republic. There were other Dutch women in Spain during the Civil War, to be sure, but they generally worked as nurses. Fanny was already in Barcelona at the outbreak of the war and participated in those July days of 1936 in the defense against the military coup. In a letter to a friend in Rotterdam she later described how she and her comrades entered the military barracks from the roofs and how they confiscated the arms found there: “I wore a rather conspicuous yellow shirt and it is a miracle they didn’t shoot me. But perhaps be they were so surprised to see me they forgot to react.” Surprised to see a girl, is the supposition, although in those days a lot of young Spanish women came into action. Fanny immediately joined the antifascist milicias and as early as July/August ‘36 left for the Aragón front, where she stayed till November when she was wounded.

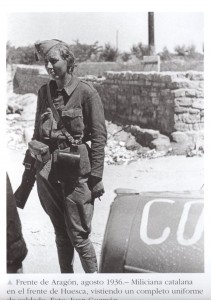

Fanny Schoonheyt at the front, in an officer’s uniform of the Republican Army. (Private archive Marisa Gerecht-López.)

At the front Fanny quickly became famous for her exceptional technical knowledge and her bravery. Almost all Barcelona newspapers—from the CNT’s La Noche to the widely read Vanguardia—published long interviews with her, calling her “la reina de la ametralladora,” the queen of the machine gun. Still, her comandante at the front assured she was “a very feminine woman,” while the interviewer of La Noche described her as tall, blonde (“a real blonde, not peroxide”) with eyes “as blue as a Nordic lake.” Fanny herself was rather averse to what she called “this adoration” and later, when several Dutch newspapers translated the Spanish interviews, she complained in letters to her friend about “all this nonsense” being written about her.

Fanny came to Spain at the end of 1934, trying to make a living as foreign correspondent. In Rotterdam she had had a job as secretary of the prominent Dutch newspaper Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant. She was an ambitious young woman, trying hard to be invited to join the editorial staff—an almost impossible aspiration in this still exclusively male world. Still, her job provided her with an entry into the cultural and intellectual circles of Rotterdam, where she met writers, painters and filmmakers such as Joris Ivens (who in 1937 would shoot The Spanish Earth, although at that point Joris and Fanny did not meet).

Earlier in 1934 Fanny had traveled to the Soviet Union. As so many young people and intellectuals in the ‘30s she was intrigued and attracted by the fame of the Bolshevik Revolution—although she had not the slightest idea of what was really going on in the USSR. She published a series of articles about her visit to Leningrad, where she was invited as art critic. Fanny was a rather talented pianist, but she likely wasn’t too interested in theoretical questions. In these articles she struggles in a naive way with the question what “revolutionary art” should be, and although she does not come to any definite conclusion, she is keen enough to predict the brilliant future of one of the composers she discusses: Shostakovich.

At the end of ‘34 Fanny decides to leave Holland, which she finds “dusty, musty, flat and boring.” She heads to Catalonia to look up the Surinam-born Dutch novelist Lou Lichtveld, one of the writers she has met in Rotterdam. Lichtveld (who, as it happened, also composed the score to one of Joris Ivens’s films) lives in Barcelona, where he is working about the colony of German/Jewish refugees who have fled the Nazi regime. In the broad Spanish political spectrum Lichtveld’s sympathies are on the anarchist side and he is a fervent anti-Catholic. His daughter, in her eighties now, vividly remembers her childhood in those turbulent days, the strikes and demonstrations in Barcelona—and especially the day she and her sister, on their way home from school, saw a chapel that was set on fire. As soon as they got home, the girls burned their doll’s house in a spontaneous act of anticlerical solidarity.

Fanny did not stay with the Lichtveld family for very long; she soon found a place of her own in the old center of Barcelona. But she never realized her dream of becoming a foreign correspondent for a Dutch paper. The letters to her friend in Rotterdam indicate that she was not doing well and had kidney trouble. She writes a lot about daily life in Barcelona, inviting her friend to join her on a trip to Ibiza (which she described as the cheapest place on earth), but she never once mentions Spain’s political turmoil. Nor does she give any sign of political commitment herself.

In fact, this is one of the many mysteries surrounding Fanny’s life: When, where, and how did she become politically engaged? Less than a year later, after the outbreak of the Civil War, writing to the same friend in Rotterdam, she is a convinced antifascist and a member of the PSUC (the United Socialist Party of Catalonia), the Catalan branch of the Communist Party. What happened in the interim?

I long thought that Fanny became politicized during the few weeks she worked as a press agent for the Olimpiada Popular, the alternative Olympic Games to be held in Barcelona in July, and on whose organizing committee sat a good number of German and Italian political refugees. When Franco’s coup interrupted the Games, several of them joined the milicias and formed the kernel of what later became the International Brigades. I supposed Fanny’s decision to join the armed Republican resistance against the coup had been a spontaneous one, motivated by a sense of solidarity with the people she had been working with in those weeks. But a conversation with Marina Ginesta in 2007 made me change my mind.

Marina, one of the last survivors of the SCW, is over ninety by now and still a beautiful woman. A photo depicting her on the roof of the Hotel Colon in Barcelona has become an icon of the SCW. During the war she worked as a translator, among others for Koltsov, the famous Pravda-reporter. Marina told me Fanny’s political activism had started much earlier: She had met Fanny at the end of ’35 or the beginning of ‘36 at the meetings of the Communist Youth in Barcelona. “It was hard not to notice her,” Marina told me. “She was tall, blonde and she smoked cigarettes! No woman in Barcelona at that time would have dared to light a cigarette in public. She paid no attention to us, young ignorant Spanish women, I even had the impression she looked down on us. The older men respected her a lot and the younger men… you can imagine.” Marina’s testimony undermined my earlier hypotheses. Could Fanny have lived a double life of which her Dutch friends were unaware?

Fanny Schoonheyt died in 1961, age 49. I have been fascinated with her since the mid-1980s, but reconstructing her life has not been easy. Reliable sources are few and far between. Apart from a handful of letters, Fanny left no personal papers; in fact, I suspect she purposely tried to erase all traces of her Spanish past. Even her daughter, who was born in 1940 in the Dominican Republic, had no idea that her mother had fought in Spain. The most extensive information about this period of her life is to be found in the Dutch National Archives in The Hague. Between 600 and 800 Dutchmen participated in the Spanish Civil War and for almost all there is a personal dossier, compiled by the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Justice. A special Royal Decree of summer ‘37 deprived them all of their Dutch nationality. Probably a third of them were killed in Spain; of those who returned—stateless—to Holland, many ended up in German concentration camps.

As it turns out, the Dutch National Archive contains an extensive correspondence about Fanny between the Dutch consul in Barcelona and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Several remarkable points jump out. In the spring of ‘37 the consul writes that Fanny has become an officer in the Spanish Republican Army. This is the time the militias, where anarchist influence is strong, are being dismantled, and the new army of the Republic, the “Ejército Popular” is being build. It is also the time of increased Soviet influence in the Army.

We don’t know what rank exactly Fanny held in the Republican army; Spanish military historians claim there never was a foreign woman officer at all. However, the uniform she is wearing on one of the few photos taken of her during the war is not the uniform of a simple soldier. Several sources affirm that Fanny was “directora” in the “campo de instrucción premilitar” at Pins del Valles, a little village not far from Barcelona where new recruits got their instruction. Remarkably, during the whole war Fanny never entered the International Brigades; she always operated in the realm of the Ejército Popular and the PSUC, the Catalonian Communist Party. Regardless of the specifics, hers was an exceptional career for a foreign woman.

How involved was Fanny in the internal political conflicts that divided the Republican camp? In his Homage to Catalonia George Orwell describes the horrible days of May ‘37, when left-wingers in the streets of Barcelona engaged in a deathly struggle, ending up with the elimination of anarchists and POUMists (wrongly called “Trotskyites”) and the violent death of POUM leader Andreu Nin. Orwell mentions the Barcelona’s central square, the Plaza de Catalunya, whose “principal landmark … was the Hotel Colon, the headquarters of the P.S.U.C., dominating the Plaza”: “In a window near the last O but one in the huge ‘Hotel Colón’ that sprawled across its face they had a machine-gun that could sweep the square with deadly effect.”

New of Fanny’s having been wounded in La Vanguardia of June 17, 1937. Click on the image to see the whole page.

In the course of my investigation I became more and more convinced that Fanny Schoonheyt had has been one of the PSUC machine-gunners at the Plaza. After publishing my biography of Fanny in the fall of 2011, ALBA’s Sebastiaan Faber sent me a photo depicting Fanny, flanked by two men, standing with her back to a pile of sandbags in front of what looks like the façade of the Hotel Colón. The picture, taken by the famous Catalan war photographer Agustí Centelles, reinforces my supposition that Fanny played a significant role in the “hechos de mayo”. Interestingly, the picture forms part of the exhibit “Centelles in_edit_oh!” which opened in New York in October. In the show, Fanny is misidentified as Fanny Jabcovsky aka Fanny Edelmann, the equally legendary miliciana from Argentina who passed away this year, age 100. (I am still hoping to identify the two men at Fanny’s side, and welcome any suggestions anyone might have on the matter.)

Centelles’ portrait of Fanny is part of a series of at least three photos taken at the same place and time. A cropped version of one of the other images—this time with Fanny smiling—appeared on June 17th, 1937 in La Vanguardia. “La gran luchadora antifascista conocida por ‘Fanny’ gravemente herida,” the headline reads. The great antifascist fighter known as Fanny, the paper states, has been seriously wounded in a car accident near Tarragona.

This is the last piece of information concerning Fanny I found in the Spanish newspapers. What she did between June 1937 and the summer of 1938 is still an enigma, although some intriguing clues can be found in a book by the American journalist Isaac Don Levine. In The mind of an assassin (1960), a reconstruction of the life of Ramón Mercader, the Catalan secret agent who murdered Trotsky in August 1940, Levine describes how Mercader, during a hospital stay in June 1937, meets another convalescent patient: “a tall, blonde Dutch girl, Fani Castedo, prominent in the communist movement. Ramon had an affair with her. His room became a meeting place for some of the most notorious communists in Barcelona as well as Soviet NKVD operatives hospitalized in the establishment.” Unfortunately Levine does not indicate where he got this information. The name Castedo is traceable to a Catalonian painter prominent in the PSUC, a friend of Fanny’s who after the defeat of the Republic disappeared to the Soviet Union. Had she adopted his name as an alias? Had Fanny entered the NKVD’s spider web?

In the late spring of 1938 Fanny tries to get her Dutch passport renewed at the consulate of the Netherlands in Barcelona. Her request is denied. She tells the consul she wants to go back to Holland—an obvious lie. The summer of 1938 finds her in Toulouse, from where she resumes her correspondence with her friend in Rotterdam. She tells here she is in Toulouse “on duty” and will go on to Paris to obtain a pilot’s license. She is reticent about the exact nature of her activities, but she does tell her friend about a man she has fallen in love with, Georges Vieux, who works at Air France in Toulouse.

Georges, a highly qualified aeronautical technician, was likely involved with the informal aid Air France provided to the Spanish Republic. He regularly traveled to Barcelona, and is there on December 31, 1938, when Barcelona is heavily bombarded by Italian aircraft. “I almost lost my Georgie,” Fanny writes to her friend from Paris, where she is desperately trying to get her pilot’s license; her lessons are continuously postponed because of bad weather. On January 6, 1939, only a few weeks before the fall of Barcelona, she tells her friend she is still determined to go back to Spain, “whatever happens.” Meanwhile, it is not at all clear why Fanny was bent on getting her pilot’s license and what she would have done with it. Was she paid by the PSUC leaders to become some sort of private pilot at the moment a hasty evacuation might be needed? As it turned out, many PSUC leaders were hastily evacuated, with Soviet help, at the end of the Civil War.

There are many questions and just a few answers. Georges Vieux disappears from the scene altogether; I was not able to find a single trace of what happened to him after the war. Fanny stays in Paris till February 1940. How she makes a living is a mystery. A little agenda covering the year 1939—one of the few personal belongings she left behind after her death—contains a long list of more or less well known antifascist artists, painters, musicians, writers. In February 1940 she arrives in the Dominican Republic, then under the dictatorship of Trujillo. She is on the lists of the SERE (Servicio de Emigración para los Repubicanos Españoles), the agency that helped Spanish refugees to leave France. After the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939, the non-aggression agreement between Hitler and Stalin, life for communists everywhere had become unbearable. The Communist Party was outlawed and many Spanish refugees ended up in French concentration camps. Fanny, who continued to be stateless, did not choose to go to the Dominican Republic; refugees were simply assigned a destination. Trujillo had his particular reasons to admit several thousands of Spanish and Jewish refugees to his country, among which “improving the race” (with “white” European blood to counterbalance the “blacks” coming from Haiti) seems to have been an important one.

Interview with a hospitalized Fanny in “La Noche,” Aug. 25, 1937. Click on the image for a larger view in pdf.

In April 1940 Fanny gives birth to a daughter, whom she will later tell that her father was a Spanish Republican fighter, named Julio López Mariani, who died on the same boat that brought Fanny to the Dominican Republic. From the documents of that time and from the research I did in Spain no such man ever results; most likely Fanny “invented” a father for her child. Regardless, from that moment on she calls herself Fanny López. She contacts the Dutch consul in the Dominican Republic and tries once again to renew her Dutch papers. The Netherlands by then is occupied by the Nazi’s, and Rotterdam has been destroyed in a massive bombardment. Fanny has good reason to hope that the information about her Spanish past has been lost in the shuffle. Unfortunately for her Dutch bureaucracy is still working and her application for Dutch nationality is denied once again. It is just because she gains the personal sympathy of the Dutch consul, Leonard Faber, that she is able to survive. Later on she starts a quite successful career as photographer. Remarkably enough she avoids almost all contact with Spanish Republican refugees that have settled in the Dominican Republic, and who according to all Dominican historians have had a determinant influence on Dominican cultural and intellectual life.

From the moment she arrives in the Dominican Republic Fanny seems bent on blurring her revolutionary past. Of course in a dictatorship it is always better to be extremely careful—and Trujillo’s rule was particularly brutal. But she becomes even more taciturn after 1947, when she is compelled to leave the Dominican Republic—the precise circumstances are unclear—and is allowed to move to Curaçao, then still a Dutch colony. Of course in the Western hemisphere in the 1940s and ‘50s there was little reason to boast of a revolutionary, communist past. But an additional reason for Fanny’s avoiding contact with her Spanish Communist comrades could have been her relation with Mercader, Trotsky’s assassin. Had that chapter of her biography become public information, her life would become even more complicated. Evidently, however, it did not: the FBI files on Spaniards in the Dominican Republic are extremely detailed, but Fanny is not mentioned.

Fanny’s silence about her Spanish past has puzzled me for a long time. When I first met her daughter, I was surprised to realize that she had not the faintest idea of her mother’s life before her birth. When I told her that her mother had been famous as “queen of the machine-gun” and the bravest girl of Barcelona, she was flabbergasted. Did Fanny hide her past only for opportunistic reasons? While in Paris in 1939, she met several Spanish artists who had been members of, or sympathetic to, the POUM. Did they open her eyes to what had really happened in those terrible May days of 1937? Did they tell her about the destructive consequences of Soviet “help” to the Republic? In other words, did she realize that in many ways she had made the wrong political choice?

Her old Dutch-Surinam friend Lou Lichtveld met her again in 1955 in Willemstad, Curaçao. She was “cool,” he said. She did not even invite him to her home. But Lichtveld had a different explanation: It was all due to the Dutch “fascistoid” government that still refused to grant Fanny her Dutch nationality: “She was stateless, so she had to be very careful.” In 1957 Fanny finally returned to Holland. She was in bad shape, her health was deteriorating quickly. On the eve of Christmas 1961 she died from a heart attack.

Yvonne Scholten is a Dutch writer and freelance journalist who has worked as a foreign correspondent in Italy and other countries. Her biography of Fanny Schoonheyt appeared with Meulenhoff in Amsterdam in 2011.

English version by Sebastiaan Faber.

Fascinating article on Fanny Schoonheyt. Any chance that an English version of the biography will be available soon?

This was a very interesting piece about Fanny Schoonheyt. What is the provenance of the third photo down from the top, with copyright attributed to EFE/Juan Guzman? I found the same photograph on this site http://www.sbhac.net/Republica/Imagenes/Armas/Infanteria/Armas01.htm

labelled 29.1.13, There someone suggests that the photograph portrays the English artist Felicia Browne. Last Summer, while researching for a concert which co-incided with the death of Felicia Browne, I discovered another website with a photo which had been found in Felicia Browne’s MI5 file by Ian Bone. http://ianbone.wordpress.com/2009/09/15/felicia-browne-only-photo-of-spanish-civil-war-fighter/

I was in touch with Jim Jump, of the International Brigades Memorial Trust about Felicia Browne and he asked if he could draw upon my discoveries for the IBMT newsletter and the resulting short item appeared with both photographs displayed on page 9 here: http://www.international-brigades.org.uk/IBMT%202011_3.pdf

If the militia woman’s photograph is conclusively of Fanny Schoonheyt then I would like to put the record straight.

Regards, Geoff Lawes

Historias como esta me siguen emocionando. Nunca me cansaré de leerlas.

On my blog there is a photograph of Fanny behind a machine gun. See this link: http://www.onvoltooidverleden.nl/index.php?id=262.

greetings, Marten

Sres.de The Volunteer queria aclararles que la imagen del boletin del 04/12/11

en un articulo titulado Fanny la reina de la ametralladora escrito por Yvonne Scholten, corresponde a Fanny Edelman argentina,miembro del Partido Comunista Argentino y en España cumplia funciones en el Socorro Rojo Internacional esta luchadora sobrevivio a la Guerra Civil 1936-1939 volvio a su pais Argentina donde tuvo destacados cargos en el Partido Comunista y en diferentes organizaciones sociales murio en el año 2011 a la edad de 100 años atte.

[…] substituït més endavant per José Piñero. La comissària auxiliar del cap militar era la tinent Fanny Schoonheyt, una periodista holandesa de 25 anys que havia participat en l’organització de […]

This was a very interesting piece of work and very useful for my university assignment, I was wondering if you would be able to send me the source of Fanny’s letters to her friend, I have been searching but am unable to find them anywhere.