ARKIVO: “My Work in Spain,” by Joris Ivens

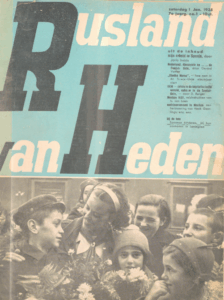

Joris Ivens (1898-1989), the Dutch documentary filmmaker who in 1937 shot The Spanish Earth—with Ernest Hemingway, John Dos Passos, Helen van Dongen, and John Fernhout—was back home in the Netherlands for a brief respite when he wrote this article for Rusland van Heden (Today’s Russia), the magazine of the Dutch Society of Friends of the Soviet Union (VVSU). Three months later, he’d be en route to China. Although the piece is little known—and has never been translated before—it offers an eye-opening reflection on the power of his filmmaking. If Woody Guthrie famously described his guitar as a “machine” that “kills fascists,” Ivens considered his film camera in much the same way.

My Work in Spain

By Joris Ivens

At the Spanish front, alongside the infantry, we watch the tanks advance. Seeing them, I think of the men who made those tanks—the men who made the first steel and iron for the fight that is now also being fought in Spain.

At moments like these, I realize how important it is that my film work never suffered the inhibiting effects of the studio. Instead, it has always been connected to real life. I have met people who hold a firm belief in their rights and in their country. I worked with them on the border of Europe and Asia, in Magnitogorsk, where I saw an entire mountain of metal that did not belong to just a few, but to an entire nation, and saw how workers transformed their country’s wealth into prosperity for everyone. I witnessed their ability to produce steel that was strong and good—the same steel, perhaps, that was used for the tanks that now support the struggle of democracy against the fascist threat here in Spain…

The comparison doesn’t just apply to the life-and-death struggle at the front. Ten kilometers behind the lines, I found myself among peasants who, under the thunder of fascist artillery, were working their own land. They were optimistic, certain of their future. In all my travels around the world, there is only one other country where I experienced something like it, and that was the Soviet Union. The feeling in Spain was the same as the one that dominated among the Soviet peasants: If we irrigate the land today, tomorrow the product will be ours. And while all this is going on, the camera is rolling. The camera experiences it, becomes part of it, and supports it. Because what is happening here is happening everywhere—here today, elsewhere tomorrow. Today’s experience can be of use tomorrow, just as the experience here can be of use elsewhere.

When I filmed Russian peasants sending cows to the mining village of Kuznetsk to provide milk for the miners’ children, I saw the same sympathy for the productive forces of the land as I saw in the Spanish peasants who sent their first tomatoes of the year and their years-old wine to their comrades in Madrid.

When I filmed Russian peasants sending cows to the mining village of Kuznetsk to provide milk for the miners’ children, I saw the same sympathy for the productive forces of the land as I saw in the Spanish peasants who sent their first tomatoes of the year and their years-old wine to their comrades in Madrid.

None of these people ever felt that the film camera was a hunter for news and sensation or a factory of vague and false illusions. It has always been a participant in—and sounding board for—their own great struggle: their courage, their joy, and their faith in the future. “Why,” people sometimes ask me, “is your composition so solid, so reliable?” What I am explaining here is the deeper reason and motivation behind it. The camera’s proper place is in the midst of life itself, serving a public that has a right to know the truth: about the Soviet Union, about Spain, about China. The truth of a people fighting for their actual future. A truth that, in essence, is the same everywhere.

I haven’t forgotten the healthy response from the Amsterdam audience to the spontaneous montages I produced years ago for the morning gatherings of the Friends of the Soviet Union. Those montages proved to be an important element as my collaborators and I have developed and deepened our work. They were already seeking to illuminate the connection between international events and the struggles of people who defend their rights against assault and oppression, as I attempted to bring together the discrete images of those struggles into an organic whole.

The same principle has guided my work in Spain, and it will also guide our work in China. We discussed filming the Chinese struggle as early as 1932, during the first Japanese invasion. Today, all of this emerges even more clearly than before in a broad international context.

Joris Ivens, “Mijn werk in Spanje,” Rusland van Heden, vol. 7, no. 1 (1 Jan. 1938), pp. 10-11. Translation by Sebastiaan Faber.

In this occasional feature of The Volunteer, whose title is the Esperanto word for “archive,” we present, translate, and contextualize iconic foreign language documents related to the anti-fascist struggle in Spain. If you have a favorite document in a language other than English, let us know!