AND ARAGON IS ON FIRE by Dr. Mirko Markovich

Martin Hourihan and Mirko Markovic

The “Spanija” series translates selected autobiographical accounts by Yugoslavian and Montenegrin volunteers of their actions in the Spanish Civil War. Dr. Ray Hoff used Google translate from Croatian to English and he edited the selections. As this is a machine translation, the idiomatic features of Croatian or Serbian and the translation of names and places are “best effort”. The full five-volume collection was entitled:

“The Participants write Spanija 1936-1939: collection of memories of Yugoslav volunteers in the Spanish War”

AND ARAGON IS ON FIRE

By Dr. Mirko Markovich (Markovic), Spanija, V3, pp269-283.

In the Scout

One year has already passed since the storm of the civil war and the German-Italian intervention raged in Spain, since without respite the Spanish people repelled the relentless attacks of the fascist well-equipped divisions.

In the middle of August 1937, just after we came out of the whirlwind of the Brunete offensive, the whirlwind of war took us to the highlands of Aragon, some six hundred kilometers away from the Madrid battlefield. The units of the legendary Lister, Modesto and the International Brigade were transferred. They were transferred quickly, in the best order and imperceptibly. The enemy was certainly surprised in the Belchite-Quinto-Ebro sector, which was evident from the fact that he met us unprepared.

Grapes ripen in the vineyards of Aragon. Here and there flocks of sheep graze on the bare hills. The days are still warm, but as soon as the sun sets, the cold mountain wind sweeps away. After the Brunete cauldron, it seems as if we have climbed the Himalayas.

There is dead silence on the entire Aragonese front, not counting the noisy discussions in the anarchist units. For a year, this gave the enemy the opportunity to concentrate the main forces in the direction of Madrid and Asturias.

The sun is setting. The shadows of the hills grow rapidly. From a distance, from the south, somewhere over there from Teruel comes the muffled rumble of artillery. This muffled thunder from a long-distance mixes with the nearby barking of dogs, the bells of sheep and the early evening calls of shepherds around the village. The battalions of the XVth Interbrigade, part of the 35th Division, diverge from the main road to the overnight camp. We were assigned a gully or as the Spanish say, a barranco at the foot of a hill. This hill certainly has its own name among the locals. Shepherds use it every day. I remember the names of the hills in my native Montenegrin region, which for every foreigner are just “hills”. Here, thoughts fly through my head: and for us, who came from all over the world to gather under the banner of Republican Spain and the Comintern, we are fighting against the fascist invasion, this hill is nameless. In fact, this is a Spanish hill, the hill of García Lorca and other numerous victims of insane fascism, the hill of the Aragonese peasants to whom the Republic gave land.

This barranca of ours covers a stunted, persistently fragrant wormwood. We will spend the night in it. We will smell wormwood. Whirlwinds will come wind. It will be cold. But that’s why we will sleep without explosions and whistling. And that’s already something. It will be cold, but at least carefree sleeping. That’s what we want the most.

And as soon as I deployed the battalion to the lodgings, impatiently expecting to lay down in the wormwood myself and sleep blissfully through the night, I was found by a courier (and couriers find everyone they are looking for) from the headquarters of the 35th division: The general is calling you!

Me? – although I know that my question is redundant, but I say it as a kind of spontaneous protest against a higher power, which does not allow me to rest.

Yes!

Under the big tent with General Walter the commander of our division, there is also the commander of the XVth Interbrigade, Lieutenant Colonel Vladimir Čopić (Senko).[i] That’s when I found out it was our first the objective is the small town of Quinto, an outpost of the enemy’s fortified position on railway towards Zaragoza on the right bank of the Ebro.

Between the fortified places on the Aragonese front stretched entire kilometers, entire plains and barrancas without a single soldier, either ours or the enemy. Quinto represented a wedge pushed into our territory. We need to cut that wedge. North-east of Quinto flows the romantic river Ebro, which is rich in water both in winter and summer. Its left bank is in our hands. “Further upstream, towards Zaragoza, that is, along the left bank of the Ebro, there is the smalltown of Pina, which is in our hands”, General Walter explains to me. “East of Quinto, but on the right side of the Ebro, our positions are in close proximity to the enemy. However, from the south and southwest, the distance between our positions, if we can call them that, is about two kilometers long. And it’s a small steppe. We will operate from there, and you will also conduct reconnaissance from there…”

I was given two days for reconnaissance, with the fact that I leave at the same time. The task included two combat reconnaissance (one at night and one during the day) by one of my companies.

“Understood?” Comrade Walter asks.

“Understood”, I answer, thinking: “Goodbye to the peaceful night I dreamed about”.

I raised the 2nd company. We took two “Maxims” and three “Tokarevs” and headed for our future sector, from which a small number of Catalan units were withdrawn that same night.

Miguel, a young Spaniard, led us along the road, between hills, through unknown coves. He surely like in his own house. I mean, this is his house. I could also lead the company through the Pipers[ii] like this. I wonder at him! The moon had not yet appeared. At times it seemed to me that we move in a circle around the same hill. Behind me, in the greatest silence, the company column stretched out, one by one. Nobody smokes. I know what it’s like for those who carry machine gun parts and ammunition boxes. That’s why I give ten minutes of rest every hour. Those who carry machine guns and ammunition take turns.

Somewhere around midnight, when we started climbing up a hill that looked like an extinct volcano to me, Miguel whispered to me that we had reached the goal. It is Cornero Hill.

I leave the company at the foot of Cornero, in the bushes and rocks. I know that these American young men spent their last strength in the forced (night march). Although we are hidden from the enemy’s view by a hill, I order the company to be well camouflaged, because there are enough stunted bushes and wormwood, and with five men Miguel I climb up the vertical Cornero. At the very top, we found about twenty of our Catalan soldiers. We relieved them. We found something like a fortified observation post, built of stone, and next to it several sandbags.

The wind whistles through the stones and wormwood. The laundry is soaked with sweat. I get chills. The moon emerged from behind the Aragonese hills, as big as a silver pan. The moonlight has flooded all the peaks, while it is still dark in the barrancas. I leave one fighter on guard “and the others to sleep.” I settled down on the stones between two sandbags.

As soon as dawn breaks, you will wake me up! I say to the other guards.

When he pulled my hand, it seemed as if I was just said those words a few seconds ago. In fact, I slept for a full two hours. The wind is noticeably decreasing. Madrugada, as the Spaniards say, the first glimmer of dawn after a tiring night. I’m taking a look. At the other end of the plain, I can see the tower of the church, which is a barely noticeable white in the morning mist. The tower clings more and more to the cover of night. ”So, it is Quinto!”, I think to myself. On the right is Purburell hill with bunkers.

The curtain of night is becoming more transparent every minute. Dawn reveals the reddish roofs of houses in the binoculars. At the western end of the town, a large white quadrangle with a high wall is clearly visible. Miguel says it’s a cemetery. Faint wisps of smoke curl more and more clearly over the roofs. Quinto wakes up. The binoculars capture the trenches and the more strongly fortified points in them. “There are probably machine gun nests,” I think, not taking my eyes off them. Barbed wire posts can be seen in front of the trenches. Apparently, the wire is placed in several dense rows. All this surrounded Quinto from the side from where we observe it. It seems to me that their fortifications are quite good, and they had time to build them, under the leadership German experts.

Between us lies the dead steppe, like the spread skin of a wild boar. No man’s land.

Through the roads here and there, I see fascists advancing. The enemy is waking up. It doesn’t even cross his mind that I follow him closely.

Using a map and observations, I draw on paper a sketch of Quinto, the enemy’s fortifications and the most suitable approaches for action.

We have been in the front line for several hours, but not a single shot has been fired. To us, who arrived from the hells of Carabanchel, Guadalajara, Jarama, Cañada and Brunete, it seems as if we have been transferred to some other country where there is no war… Red – the black banners on the hills of Aragon, which were carried by Catalan units of anarchists, frighteningly marked the “line” of the front, but here, so to speak, the fighting was not fought. When I told Miguel that it was hard for me to believe that “ours” were in the field between two fronts playing football with the enemy, he swore on everything in the world that it was true. And it was not a rare case that people from the enemy garrison came to visit their relatives in the Republican territory and returned to Quinto. “Then it’s no wonder” – I think to myself – “that Franco was able to concentrate the bulk of his forces near Madrid”.

As far as I can see, one quarter of Quinto, that side towards Zaragoza, has no fortifications. I record all this in a sketch, which I draw slowly and precisely. I hand over the binoculars to Lieutenant Domjanović, and I go down the hill in the company. A rest of a few hours brought a brighter mood among the fighters. I found them distributing breakfast. White coffee and bread arrived from the background. There are noticeable traces of salt on the protective color shirts. It is from profuse perspiration during last night’s strenuous march. Chubby Miller, the company commander, informs me that everything is fine.[iii].

The machine guns are assembled, lubricated and ready for use. do it!

I tell Miller that after breakfast the condition of weapons and the amount of ammunition at our disposal should be checked in all platoons, because, according to the plan, we will carry out the first combat reconnaissance exactly at midnight.

After a short conversation in the company, I return to the observation post. “Anything new?”- I ask Domjanović.

“Nothing!”, he replies without interrupting his observation. Rats flit carelessly back and forth. Certainly, most of them are in Quinto itself, in houses. In all probability, that garrison still was not in the fire, but we will give them a turn.

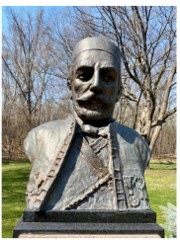

Milo Damjanović, a Montenegrin from America, is a very experienced warrior. We have been inseparable since Jarama. He is almost two meters tall, and has a large, hooked nose, which reminds me of the nose from Njegoš’s bust

Figure 1 Bust of Njegoš.

Figure 1 Bust of Njegoš.

The sun is already hot. I’m lying between two sandbags. The sight captures the field near the cemetery, where several platoons are training. They are probably recruits. It drifted off a little further in the morning some goats, sheep and donkeys…

A small greenish lizard crawled up to the binoculars itself, which I leaned against a stone so that the sun’s rays did not fall on the glass. It seems that he was interested in this little observation device. Resting on its front paws, the lizard raised its head and thumb with its small black tongue. Quickly and breathing with his belly, he carelessly turns his head sometimes to one side, sometimes to the other. Hunting flies. “He doesn’t care” – I think to myself – “what imperialist countries are, in the name of non- interference in internal things blocked the Spanish Republic…”

The scope catches the enemies, naked to the waist, walking between the trenches and Quinto. And a little later, we watched them how sunbathe around the trenches and even on the ramparts of the fortifications.

It’s hot. The day dragged on and on. What could be seen from here I had already seen and transferred to the sketch. I am waiting for the night, so that we can carry out a combat reconnaissance, to force the enemy to show his teeth…

I already have a plan: I will send two platoons straight from the observation post, across the field in a frontal attack. There we will use one “Maxim” and two “Tokarovs”. I will send one platoon with one light machine gun to the extreme left wing of the enemy, to investigate what kind of fortifications there are on the hill east of Quinto. At the same time, I will send Domjanović with the wizened Miguel and three other fighters in a faint from the western side, towards the cemetery, with the aim of capturing the fascists alive.

The commander and the political commissars, as well as all sergeants, were thoroughly familiar with the task. At first dusk, the plan was explained to all the fighters. I have been fighting with these young men for almost a year. We know each other well. I was confident of success. They are brave sailors, miners, students… They are disciplined and have initiative.

Around ten o’clock in the evening, in the greatest silence, the movement in groups began. The width of the reconnaissance front was about two kilometers. With one platoon and one “maxim” I walked in the middle of the field, between the right and left platoon, at a distance of several hundred meters. The task of the platoon that was with me was to come to the rescue where the reconnaissance did not take place according to plan. We were like a kind of reserve.

The enemy gave no signs of himself. Everything was calm. When the clock showed midnight, I fired a red rocket.

The platoons opened heavy rifle and machine gun fire across the entire front. The enemy, with some delay, hastily and unorganized, started shooting in all directions. They also fired a dozen light rockets, especially from the eastern flank of Purburell. And when, after the first volleys, our platoons hid, the enemy opened intense fire. In the course of a few minutes, I was able to “locate” about fifteen heavy machine guns, and two mortars “rang out” from the enemy’s left wing, from the fortified Purburell hill.

After half an hour of “feeling {them out}”, I fired a blue rocket as a signal to withdraw. We had six wounded. Fortunately, no one was killed. But I didn’t know what happened to Domjanović’s group until three after midnight. Finally, he answered. He brought with him a small, plump corporal of Franco’s, with a red beret on his head. A sign that he belongs to the Carlists (monarchists). Thanks to Miguel and his Spanish, they rolled him up somewhere behind the cemetery, gagged him, put him in a sack, carried him and shook him out of the sack only when they were in the safe zone. The corporal was shaking so much with fear that he was pitiful. Shaking his head and stammering, he tried to answer the questions. It took us an hour to get him to speak. Hot coffee, cigarettes and Miguel’s boots contributed to this.

At my observation deck, the second morning began. Again, the tower of the church emerged first from the haze. On our side, there was complete silence. No sign of the night raid anywhere. It must have looked to the enemy as if night spirits had attacked. I believed that the missing corporal would cause alarm among them. We touched the wasp, and now we need to let it calm down.

Together with the company commander, the platoon commander, and the platoon commanders, I noted in detail on the sketch all the important firing points of the enemy.

At ten o’clock General Walter’s courier arrived. I wrote a report and attached a very detailed sketch of the enemy’s positions. I also sent a proposal not to conduct daily reconnaissance, which it would not reveal anything new to us, and it would cause the enemy to be more wary and will caution them and suspect that we are preparing something.

In the afternoon, I received the General’s praise and agreement with my proposal. In Walter’s message, it was said that I should pay the main attention to the railroad from Zaragoza, and to determine whether the garrison of Quinto, which according to our estimate numbered about 1,500 men, would receive any reinforcements during the coming night.

The Conquest of Quinto

On the Cornero hill, at the observation tower, the third dawn of the morning begins. Even before that, at night, our sappers set up a command post, and the division’s telephone operators set up lines along the hill. The phone worked. The commander of the 35th division, Comrade Walter, also arrives.

Unforgettable August 24, 1937, dawns. During the night, on the eve of this big day for us, the battalions took starting positions. The striking force of the division is the XIth and XVth Interbrigades. The General asks me for the most favorable directions of action. It has already been distributed. The entire field is in front of us as if in the palm of our hand, because the observatory is at a height of three hundred meters.

The division commander has his hands full. Receives reports about the completed tasks, gives new orders, but all this takes place without nervousness and evenly. Walter is in his shirt, so he unbuttoned it as well, although it is cold, because the sun has not yet risen from Lerida. From time to time he rubs his bald head with his palm.

They announce that the transport with artillery ammunition is not arrived. The general’s face is as red as pepper from anger: “Such managers should be driven to hell (to the mother of the devil)! What have you been doing all night!?” he asks the officer who brought the report. He picked up the phone and scolded someone over the phone the other end of the line.

Then he took a look…

I started to feel redundant at Cornero’s Plana Mayor.[iv] I spent two days and two nights there. I did what I had to do. I knew that my battalion was slightly to the left of us ready to perform. It seemed most logical to me to go down to the battalion and take command. But when I asked Walter if I could go to the battalion, he answered: “Stand down!” I too “crazy”. A crazy battalion.

And the battalions are moving. The “Dimitrovs” are going across the plain, straight to the enemy’s positions. I know that in front of the trenches they will come across a shallow riverbed (we passed it the night before during combat reconnaissance), which nevertheless provides a little cover. The English battalion is on our right wing – in the direction of Purburell. Between these two battalions, the Spanish battalion from the XVth brigade is advancing, and the Americans are advancing on the left wing of the brigade, in the direction west of Quinto. The XIth Interbrigade is even further west, as there is a rather unexplored enemy fortification about three kilometers from Quinto, towards Belchite. The task of this brigade is to cut off the enemy’s retreat towards Zaragoza.

The enemy fired several artillery shells at our infantry, trying to disrupt their advance. It is nice to see from the command post how the shells explode behind our units. They raise columns of sand and dust across the barren steppe. No harm done. The guns were joined by heavy machine guns. They open fire from the area of the cemetery. Several shells exploded on the left wing of the “Georgi Dimitrov” battalion.

It started to rain fire everywhere. The machine guns rattled. “Aragon caught fire too” – I think to myself.

The battalions are performing well – says Walter. Just don’t let the aviation be late!

He looks at his watch. At five minutes past seven. Just make sure he’s not late!

First, a powerful war machine was launched in an area of ten square kilometers. Everything is in a state of tension. The first sparks flew. The control apparatus of this machine is in the safe hands of a man who knows his job. Walter presses one or the other “button”. Everything moves quickly and evenly.

A Soviet officer came with the report.

Comrade General, the artillery ammunition has arrived!

“Excellent! Just in time!… As long as the planes are not late” answers Walter.

Rifle and machine gun fire is getting stronger and denser. Behind the mountain range, far from Lleida, the sun appeared. Plains and Quinto in front of us are still in the shadows. The wind stopped. The fascists poured heavy fire in the hope of stopping our advance. But it’s all just a prelude to the symphony of battle to come. Enemy shells explode in the sandbox. Our wounded are quickly pulled out by the paramedics to the rear. From the ravine that separates Quinto from the fortified hill of Purburell, a saddled horse as white as snow suddenly jumped out at full gallop. Like a madman, he rushed across the plain where one company of the Georgi Dimitrov battalion was located. Two fighters cut his path and caught him. At the same moment we all turned our eyes to the east. That’s where the steady sound of airplane engines came from. In a few seconds, it turned into a terrible thunder. Our squadrons were coming. We were elated.

Walter smiles: “They didn’t let us down!” The clock really showed 7 hours and 5 minutes. Our falcons aimed at Quinto. The hills trembled as if from an earthquake. The echo is carried from mountain to mountain, as if some terrible giant were laughing. I hear someone say: “The Fascists must be fed up!” The positions around Kinto are surrounded by thick black smoke. Even the rays of the sun cannot penetrate it. The steel birds have risen, but they are not leaving, they are circling over Quinto. that. The smoke is lost in the field, the bays, the Ebro bed. Then they did planes descend lower and bombed again.

The enemy is silent. He is dazed. Not a single shot.

“Artillery is ready!” they report to the general.

“Open fire on the first line of the fascists!”

The work started by aviation is continued by the artillery. “Meat” in the first line of enemy fortifications. After each explosion behind barbed wire holes are opened. Pillars of earth, stones, dust are rising… The symphony of the battle is growing. Rumbles everywhere. The sun burns fiercely.

Creeping, our battalions are getting closer to the enemy. And I know for a fact that two little things bother us the most right now. The first, that probably every fighter has already emptied

his flask, and now it is impossible to get water to such a mass of men. It will remain so until the first darkness. Another thing is the tiny thistles, a stunted plant with thousands of needles. It covers the entire steppe through which our people crawl. And you have to crawl – on your knees and elbows, on your stomach, because there is no shelter. These damn needles pierce through clothing and into the skin. Over a period of time, numerous purulent bubbles appear on the skin, which causes fever.

It is not difficult to lose a life in this raining bullets. You should get as close to the enemy as possible, and then jump up to charge. Every fighter saves his life for that jump.

Walter orders the artillery to fire on the second line of the position. It was also a signal to our units to attack. The three battalions rose but stopped in front of the enemy. They did not

overcome two obstacles: dense rows of barbed wire and machine gun fire. And it seems to me

that the distance that had to be covered in the assault was too great. I remember something similar happened to us at Villanueva de la Cañada: aviation and artillery did their job, but the infantry was late. There, it is enough for a few minutes to pass before the enemy recovers and opens fire.

Here, for the first time, we failed to carry out the operation plan. I was sent to help organize the assault.

In half an hour, tanks will arrive to help you. You must capture the enemy’s positions! Understood!

Understood! With a few companions, I rushed down the hill, on the side facing the plain, towards Quinto.

I went to the sector of the “Georgi Dimitrov” battalion. The fire from machine guns and rifles sweeps across the field. I reckon since there are no Moroccans in Quinto, there are no snipers either. In the Brunete offensive and at Jarama, they were quite effective. But you have to crawl. in a shallow cove, I find a large number of our wounded. They say they told the battalion doctor to come.

On the left is the “George Washington Abraham Lincoln” battalion[v] and on the right the Spanish battalion. I am transmitting the order to all three battalions. Our artillery is again pounding the front line of the enemy’s position. Several anti-tank guns were brought into the immediate vicinity. They are very efficient.[vi] They are demolishing machine gun bunkers.

The tanks also arrived. They rolled along the thick barbed wire and tore it out. And when they showered the Fascists with flames from the flamethrowers, the battalions jumped on the charge, followed by a strong u-rrr-aaa!”.

The enemy did not last long. He retreated towards the city. The companies jumped into the trenches, occupied them, and broke out into the clearing – towards the cemetery. In that rush, we occupied some alleys of Quinto. We were bombarded by heavy machine gun and rifle fire from the church, from some houses and from the hill east of Quinto. Our main protection was the cemetery with its high thick walls.

On a hill in the middle of the town of Quinto, the church dominated. Fascist officers turned it into a fortress.

Another cold Aragonese night was descending. Our units were being organized. The dead had to be buried, and the wounded had to be transported to hospitals. August 24, 1937, was a long and bloody day.

I passed happily. During the attack, a bullet caught my left shoulder. “Medico” bandaged my wound, it burned a little, but everything was fine. Sometime later, at the cemetery, I got a slight scratch on my left thigh.

By dark, we captured about 600 enemy soldiers and some officers. The rest mostly got married in the church. It was simply incomprehensible how the fascists lived in such clouds of fleas for a year. Namely, while we passed through their lines, shelters and bunkers, we got so full of these little angry insects that we stripped down to our bare skin all night, trying to get rid of them.

The Struggle for the Church

I spent the night in a frenzy. Fatigue, fleas, pimples on my knees and hands, a wound in my left shoulder and constant shooting, sometimes here, sometimes there, prevented my good sleep. Morning found me quite broken. Walter’s phone order also arrived: “Hurry up with the cleaning of Quinto… Take the church, but don’t demolish it… All this should have been done yesterday!”

“I was in charge” of the church. It wasn’t even daybreak yet, and the population started to get out of the alleys and run to us, towards the cemetery. Behind the walls of the cemetery, where the operational headquarters was located, a mass of women, children, and old people gathered. In some places, the fight was conducted from house to house. But all this was relatively easy compared to the fight for the church, where, according to the information I received, they were enemy officers who do not even think of surrendering. They are waiting for help from Zaragoza.

It completely gave away. It smells of gunpowder, of cinders. Everything is somehow worn out, tired. The fascists from the church are shooting not only at our fighters, but also at the locals who are fleeing towards the cemetery. Distraught women run away, uncombed, shaggy, and carrying small children in their arms. The old men are walking behind them, helping themselves with sticks. Boys and girls, tucking their heads into their shoulders, run faster and more skillfully. They are running away from the fascist enemy who is shooting at them in the back from the church… An old man detached himself from the shelter of the last house and tries to cross the cleared area in front of the cemetery as quickly as possible, but the burst from the church overtakes him. He hit the ground with his face.

An entire camp was created at the cemetery itself. Our kitchens they work tirelessly, distributing food to the people.

We are sending a platoon to help the population hide behind the houses, because we see that this way Franco’s officers will cut them down with fire from the church.

At the cemetery, our men attracted three cannons, which are pounding the bunkers on the hill east of Quinto. Over the phone, I ask permission from Čopić, and later from Walter, to fire a few grenades into the church, in order to force the fascists to surrender. The order is:

“Drive them out of there without demolishing the church!”

I took a platoon of fighters from my battalion, several crates of hand grenades, a bag of old rags and two buckets of gasoline. Through the winding streets, from house to house, we emerged on the hill into the church’s paved courtyard. We deployed along its walls to avoid rifle fire. I went around the whole church. There are only thick walls between us and the fascists. On the eastern side, next to the altar, there was a tall narrow window, through which we threw something like a bomb. Explosions rang out, followed by moans. Then we threw in some rags soaked in gasoline and set on fire. I guess it’s a real hell inside with explosions, flames and smoke and I’m yelling at the fascists to surrender. If they can’t do otherwise, I tell them to approach the somewhat wider window on the north side, let them raise their hands, and we will pull them out. “Quiet!” After a few minutes of silence, they responded by shooting through the windows and under the roof.

We throw in a new “batch” of bombs and flares. We continue like this for ten minutes. The first hands appeared at the marked window and shouted: “We surrender”.

Our fighters are pulling the fascists out of the window. There were wounded among them. We line up Franco’s officers thus extracted next to the very wall of the church. One of the last ones we pulled out was waving with only one hand. We pulled him out by that one arm. Right shoulder gaped. Blood gushed from the open wound. He says a bomb dropped on him from above under the roof, which took off his arm.

Well, that’s fascist “solidarity”! – remarks Lieutenant Domjanović.

We pulled out a little over seventy of them out. There were still about fifty of them alive in the church, who did not want to surrender. I left the platoon of fighters under the command of Lieutenant Domjanović at the church, and led the prisoners towards the cemetery. Along the way, two of them were shot in the back by their friends from the church.

As soon as I handed over the captured Fascists and sat down on a stone next to the cemetery wall to rest, Dani, a student from New York, arrived from the church. Even as he approached me, I noticed that his emaciated and unshaven face was covered with some sadness.

“What is it, Dani? “- I asked him in a tired voice, as if I had to, because it seemed to me that I didn’t have the strength to stand up, even though General Pozas himself, the commander of the Eastern Front, was in front of me.

“Comrade commander, Lieutenant Domjanović was killed!”

Although we look death in the eye every hour, this news hit me like a thunderbolt. In a moment I covered my face with my palms… Milo Domjanović! How many times has he saved my life! How many times have we argued about who will drink the last sip of water from the flask, who will take the last smoke from the cigarette we smoked together… And a hundred other times”. Ah, what a fighter fell!

I got up and went towards the church. That was, I guess, the first time if I hadn’t listened to the whistles of the bullets.

Next to the wall lay the long, thin, motionless body of Lieutenant Domjanović. The bullet hit him from above in the head, passed through the neck and exited between the shoulder blades.

We took the dead comrade and retreated with the whole platoon towards the cemetery. I ordered the gunners to aim the barrels of all three guns directly at the church. The thick wooden doors of the church flew away from the first shells, and the passage itself became twice as wide. After each shell, new holes were opened in the front wall. Fascists started popping out through those holes. They surrender.

“Cease fire!” I order the artillerymen.

After a few hours, I had to give an explanation to an enraged General Walter for violating the order not to demolish the church. I began with a detailed presentation of the situation regarding the church. Walter slyly squinted his blue eyes and after a few seconds interrupted me:

“I’ll let it go, but tell me honestly, but as openly as a communist does to a communist, what made you break me order and demolish the church with cannons? You tell me that!”

There was nowhere to go and I told him about the death of my closest friend…

Fortunately, the old hardened communist Walter was able to understand the personal pain of the man and after he explained to me that “a communist must never allow something personal to cloud his mind”, and since I gave him the word of honor that it won’t happen again with me, let’s drink a glass of vodka (but real) in honor of conquering Quinto.[vii]

In the evening, on August 25, two fighters from the “Georgi Dimitrov” battalion brought a thin, tall, unshaven old man to the cemetery. He walked sullenly. He was carrying a colorful blanket on his hunched back. A young, beautiful woman was following him, carrying the child in her arms. She walked defiantly, proudly, and with a smile. In her large black eyes, pleasure, revenge sparkled.

“Don’t you have a smarter job than to lead that old man?”, someone asked.

One of the “Dimitrov people” explains that a rifle was constantly firing from the old man’s house and that two fighters were wounded in front of the house.

And when we went inside, we found no one except an old man and this woman with a child.There was also a rifle with plenty of bullets and empty cartridges. He must be a fascist. And now you investigate the find out.

Since the old man is silent as if stunned, we ask the young woman who he is man?

Gathering her arched eyebrows in a spasm of hatred, the woman pointed her finger in the old man’s direction: “This bloodsucker is my husband! He was the leader of the fascists in Quinto. He forcibly took me as a wife from poor parents, even though he could have been my grandfather by age. A year ago, many people were killed by his verdict, including my fiancé. For a year, Quinto trembles before this villain.

The nimble Miguel soon brought a Spanish fighter who was from Quinto. He managed to escape a year ago. He worked as a railway worker. He says that he knows the old man very well and claims that during the capture of Quinto by the fascists, over two hundred communists, socialists and anarchists were shot on the old man’s orders.

Sitting hunched over, the old man, without raising his head, turns towards to the young woman. He looks at her slyly, like a caught wolf. The same view transfers to the railwayman from Quinto. He doesn’t say a word.

The units of the 35th division are preparing for the campaign.

We are heading in the direction of Belchite.

General Walter receives a telegram from the Eastern commander front: “From the bottom of my heart, I salute the commanders, commissars and fighters of your brave division, and especially you, as well as the XIth and XVth Interbrigades, for the heroism they displayed in the ingeniously organized performances during the conquest of Quinto. Your victory is of enormous importance for the success of our common cause. I am confident that this victory will be surpassed by the strength of the units of your division in new performances of equally great importance. Forward 35th division!”

Dr Mirko Markovic

[i] [General Walter] Karol Swierczewski, a well-known Polish communist, participant in the October Socialist Revolution, member of the Central Committee of the Polish Workers’ Party and deputy defense minister of Poland after World War II. He was killed in an ambush by fascists in 1947.

[ii] A tribe in Montenegro.

[iii] Alex Miller, Canadian, was Company Commander of Company 1 of the Washington Battalion and was wounded at Quinto – rmh

[iv] Originally written as PM, an acronym for Plana Mayor or in English headquarters. – cb

[v] The Abraham Lincoln and George Washington battalions were merged during the Brunete campaign. – cb.

[vi] These were likely the British Anti-Tank Battery. – cb.

[vii] Many years passed when I met again the other Svjercevski in the winter of 1946 in Belgrade. He was the deputy minister of defense of Poland, and he came to Belgrade at the head of a delegation of Polish volunteers in the Spanish Civil War. We had dinner at the “Mažestik” hotel. The meeting was very cordial. And his first words after hugging me: “So you’re alive! And I silently chased you in Quinto! Do you remember that curmudgeonly daughter…?” How hard it was in my soul when, after a few months, I found out that this great, meritorious son of the Polish people had fallen to the hands of the fascists, and that in his native land.

Photo credit International Brigade Archive, Moscow: Select Images, Folder 191: Commanders of the 15th International Brigade, 1937-38, Box 2, Folder 17; ALBA Photo 177; ALBA Photo number 177-191043. Tamiment Library/Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives. Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, 70 Washington Square South, New York, NY 10012, New York University Libraries.