Refugees from McCarthyism in New Zealand: The Story of Bob and Augusta Ford

Bob Ford, who worked in Hollywood and fought in Spain and World War II, suffered relentless surveillance because of his radical past, as did his wife, Augusta Ain. In 1950 they moved to New Zealand—and never looked back.

4 February 1938

We just returned from Madrid. We had rather a good time except the last day when the fascists dropped 18 shells into town. There wasn’t much damage or anyone seriously injured, but they dropped one right across the street from us… Madrid is a swell town and I like it very much. The only thing is the Spaniards will bever get used to my size. They turn around in the street and stare at me.

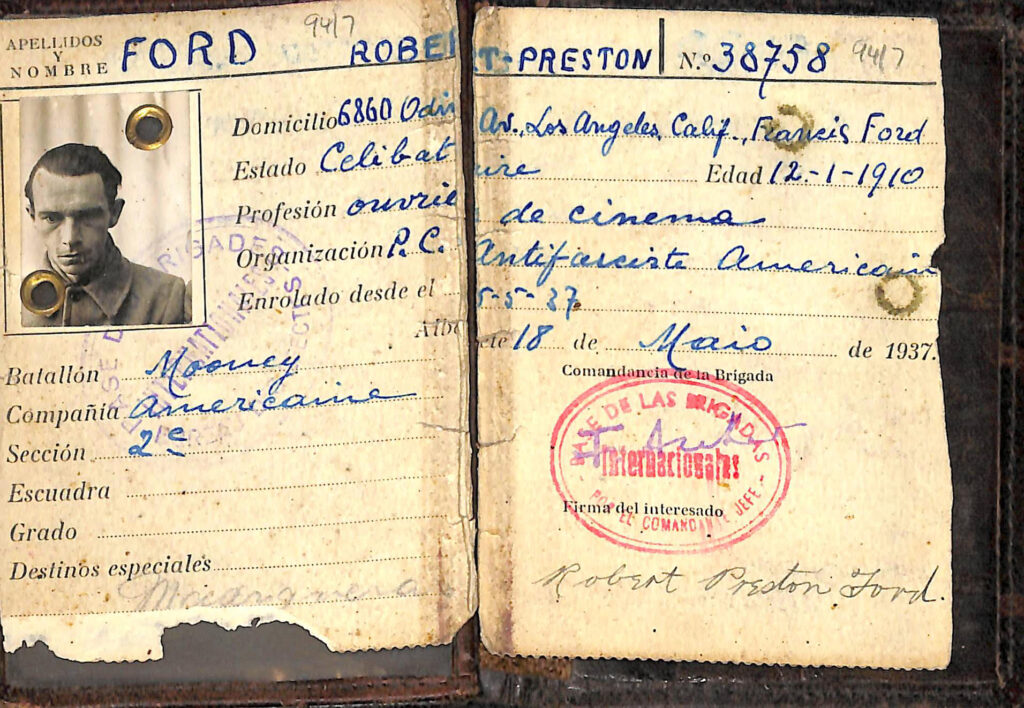

Standing around six feet tall, Bob Ford was a distinctive figure even among his fellow members of the Lincoln Brigade. He arrived in Spain in May 1937 and enlisted in the Mooney Battalion as a Communist Party member and “anitifasciste Americaine.” Details of his combat service are few but he is known to have taken part in the battles of Brunete from mid-1937 and the Ebro in late 1938. He was evidently ill or injured for much of that time, spending a week in hospital in September 1937, and the next five months in another at Valdeganga de Cuenca.

Nevertheless, he remained in Spain until ordered to depart, along with all other International Brigade members, in October 1938, and returned to the US bearing the Carnet de Honor awarded to combatants in the Republican Army’s 35th Division.

Every week or so throughout his service in Spain Ford dashed off a postcard to “Nana and Bill,” his relatives in California. The rigours of wartime censorship ensured that the pictorial side of these cards is usually more eloquent than the few words he wrote on the back. Ford recognised this himself, admitting that there was very little he was allowed to say about his own activities, although the cards, illustrated with images from Republican propaganda posters, were worth sending in their own right. “All over Spain you see posters like these,” he wrote in October 1937, “issued by the Propaganda Ministry and the various political parties. The finest artists in Spain draw them – they are all very interesting and forceful. And some of them are of great beauty.”

“I unfortunately did not see or hear Paul Robeson while he was here,” he revealed in March 1938, “but I am glad that he came to Spain. I believe that he is a communist and if that is true, it is a good thing. We need men like him in the revolutionary movement as he is both popular and intelligent.”

“You ask me in all of your letters when I am coming home,” he wrote soon after his arrival in Spain. “I really can’t say even if it wasn’t for the war…” (and the next line is blue-pencilled, presumably by the military censor) “there are personal reasons that will keep me in Spain for a long time.” What those reasons were we can only surmise but a later card, sent in March 1938, makes clear his admiration for the country he had chosen to fight for. “This is a marvellous country and the Spanish are swell people, and when we have finished with the damn fascists it will be one of the best countries in the world.”

Urgent requests for cigarettes are a repeated theme in Ford’s postcards from the civil war, along with anxious queries about his father. “I would like to get some late news,” he wrote in October 1937, “so I would know what my old man thinks of me being here.” Six months later he had still not heard from his father. “I don’t know why his letters have not reached me, that is if he has written to me and put the correct address on the letters.”

Francis Ford, the father whose approval Bob evidently yearned for, was a well-known Hollywood actor and director who began making Westerns in the silent-movie era. His younger brother John developed a more illustrious career movie, making classics like The Searcher with John Wayne. Before his tall and rangy nephew left for Spain, his uncle cast him in a number of small parts in his films, and on his enlistment papers Bob gave his occupation as “cinema worker.”

Upon his return to the US, Bob Ford evidently made no attempt to call on family connections in the movie business to evade further military service. Like many another Lincoln Brigader he enlisted for WWII at an early opportunity and spent the next several years as a military policeman stationed in Europe. This was a posting for which he was ideally suited physically, since he looked huge and authoritative in an army greatcoat, although his disposition was fundamentally gentle and non-violent.

During the war Ford also married. Augusta Bebel Ain appeared quite unlike him in most respects – diminutive, myopic, with a shock of frizzy hair and a radical pedigree. Her parents were Russian Jewish immigrants who named her in honour of a German socialist orator who died the year she was born, and her family spent some years at Llano del Rio, a utopian socialist colony on the edge of the Mojave Desert. Despite their sharply differing backgrounds, Augusta and Bob remained soulmates for life, enduring many difficulties and disappointments.

In the late 1940s Augusta studied at UCLA Berkeley, writing a thesis on US folk music. She and Bob formed a student cell of the US Communist Party but soon realised that its other members were FBI informants. Both the Fords were subject to relentless state surveillance because of their radical pasts, and they soon chose to leave the US permanently. In 1950 they departed on a passenger liner, never to return. Why they chose to resettle in far-distant New Zealand, where they had no friends or relatives, is not known but they may have been influenced by reports of that country’s progressive Labour government, first elected in 1936. If so, it must have been deeply disillusioning to find that the year before their arrival in New Zealand, Labour had been replaced by a very conservative, stridently anti-union government with close ties to the US administration.

Nevertheless, this odd and anomalous couple re-established themselves on Auckland’s North Shore, and eventually made close friends there. Bob, who had received training after the last war as a lathe operator, took a job in a factory that made parts for the plumbing industry. He spent the rest of his working life travelling daily to this small firm, working at a machine intended for operation by a much smaller man. Augusta found a more fulfilling job teaching English, first at a local high school and then at Auckland Teachers Training College, where she exerted a profound and lasting influence on many of her students and colleagues. She further extended her cultural influence through a series of radio broadcasts on modern American literature and music, paying special attention to Black and feminist artists.

After some years of renting and saving they were able to buy a small house, sparsely furnished but lined with books. Its large windows drew attention to their lack of interest in cleaning them. Augusta was “an intellectual who utterly refused the job of housewife,” according to one of her former students. Yet she and Bob, while childless themselves, proved devoted babysitters to their neighbours’ children, willingly reading to them by the hour. They were also generous and unconventional hosts, introducing a succession of New Zealanders to such exotic dishes as giant T-bone steaks, Mexican tamale pie and baked cheesecake, served with endless glasses of red wine and, one guest remembers, “ferociously strong coffee.”

Both the Fords smoked incessantly, and their spartan house was invariably acrid and unkempt but always filled with music, mostly from Bob’s extensive collection of jazz 78 records. He enjoyed discussing art and politics with friends and neighbours in his slow-spoken, deep drawl, and he and Augusta played a small part in anti-apartheid protest activity. They were unusually generous despite their few resources, lending at least one young couple the finance they needed to buy their first home.

The couple showed no indication of wishing to return to the US and became naturalised New Zealand citizens in 1970. They appear to have never owned a car, and very rarely travelled at all, although they received occasional visits from US relatives such as Augusta’s brother Gregory Ain, a well-known and controversial California architect who, like the Fords, had been subject to McCarthyite witch-hunting.

As they aged both the Fords’ eyesight and hearing deteriorated, leaving them even more than usually isolated in their adopted country. By the early 1990s they could no longer remain in their house and were moved to a rest home where they occupied separate rooms. Bob Ford died within a few months of this move, and his wife lingered on until the following decade.

Whether the Fords ever regretted their decision to live in New Zealand is not known. Their life there appears limited and uneventful, although they inspired the admiration and affection of a circle of close friends. Although Bob apparently had no interest in maintaining contact with fellow veterans of the International Brigades, he ensured that his postcards from Spain were deposited in the Auckland Museum. Another memento of his service there held less value for him. While moving from the house he had shared with Augusta for almost 40 years, he retrieved his Republican Army revolver from a closet and flung it into overgrown waste ground behind his property, where it was never subsequently found.

Mark Derby’s biography of Doug Jolly, a New Zealand surgeon who served with distinction in the Spanish Civil War, will be published in June 2024.