Liberating Palestine in Spain: Novel on Palestinian Arab Volunteers in the IB

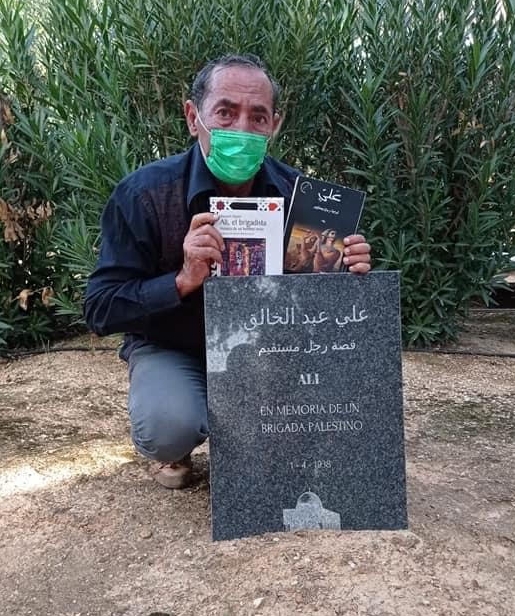

Yassin with the Arabic and Spanish versions of his novel next to the tombstone he erected for Ali in Albacete cemetery, Spain.

Framing its protagonist’s journey to defend Spanish freedom as an extension of Palestinian Arab resistance at home, Hussein Yassin’s novel sheds light on the turbulent history and the political and social contexts of pre-1948 Mandatory Palestine.

“I am an Arab volunteer who has come to defend the Arabs’ freedom on the Madrid front! I have come to defend Damascus in Guadalajara, Jerusalem in Cordoba, Baghdad in Toledo, Cairo in Andalusia, and Tétouan in Burgos.” These words were published in The Vanguard in June 1938 by Najati Sidqi (1905-1979), a leading member of the Palestinian Communist Party (PCP) who joined the Spanish Civil War to combat fascism and support freedom. The quote reappears in Ali: The Story of an Honorable Man (2017), in which the Palestinian novelist Hussein Yassin recounts the journey of Ali Abdel Khaleq, a farmer, member of the PCP, and one of five Palestinian Arabs—as opposed to “Palestinian Jews” who also lived in the pre-1948 Mandate Palestine—who volunteered in the International Brigades in defense of the Spanish Republic against Francisco Franco’s nationalists. The others, in addition to Najati Sidqi, were Naguib Youssef, Fawzy Sabri Al Nabulsi, and Malih Al Kharuf.

Ali, Yassin’s third novel, documents a historical episode that helps debunk the notion that Arabs only collaborated with fascist regimes in the 1930s and 1940s—exemplified by the 250,000 Moroccans who fought in General Francisco Franco’s army and who had been recruited from what was a Spanish protectorate. In addition to the five Palestinian Arabs mentioned, IB volunteers from the Arab world included seven Palestinian Armenians, the Iraqi Nuri Roufael Kotani, a Syrian, a Lebanese, many Libyans, Tunisians, and Algerians, in addition to Mizrahim. “With the exception of Sidqi’s writings, Arabs did not record this part of history, which made them completely absent, as if they weren’t part of history,” Yassin told me when I interviewed him in the fall of 2022. “I was ashamed of this absence and thought I should make up for this shortcoming.”

During Yassin’s search for Palestinian Arab volunteers in IB, he came upon a book by German historian Gerhard Hopp that identified the names of Abdel Khaleq and Al Nabulsi among those who fought in the Spanish Civil War. This prompted the novelist to enthusiastically embark on a five-year endeavor to track down their story, leading him from Moscow to Spain. He learned that Ali left Acre’s prison to go directly to Spain, where he was quickly promoted to be one of the commanders of the Botwin Company. He was shot on March 17, 1938, on the Madrid front, and buried in Albacete. “My novel attests to the Spanish tragedy,” he told me. “It attests to my sympathy with its people and to the commemoration of the Palestinian Arab volunteers, the heroes who left their embattling home and fought for a free Spain against fascism, Nazism, and destructive capitalism. They did not demand anything in return save the honor of being counted among its fighters. I resolved to identify those unknown heroes.” In Ali, the Palestinian Arabs’ willingness to fight fascism in Spain becomes emblematic of the struggle for a better future, free from imperialism, inequality, and oppression.

While Palestinian Arabs were not politically tied to Spain, Yassin explains, their defense of the Spanish Republic extends their “resistance to the first true enemy: The British oppressive occupation of Palestine” that supported the Jewish settlement project and worked in alliance with the Anglo-Jewish philanthropists. Ali’s upbringing as a farmer embodies the tragedy of the Palestinian fellah or peasant whose “dispossession by Zionist land-purchase became acute” in the 1930s amidst a rapidly growing Jewish population, as Rashid Khalidi has written in Palestinian Identity. Ali’s struggle as “a national hero” who, as Yassin discovered, was imprisoned several times by the British for expressing his opinion and who went on a hunger strike for approximately 19 days reflects his belief “in bridging people through love, social justice, and personal freedom,” Yassin told me. It also conveys the significance of these universal values to conjoining the combat in Spain. This resonates with Sidqi’s testimony from 1938:

I noticed that the volunteers in the Republican ranks and those that constituted the International Brigades were a mixture of Frenchmen, Englishmen, Italians, Ethiopians, Americans, Chinese, and Japanese. A brigade of Arabs, too, had come from various Arab countries, so I said to myself: truly, there is no excuse for excluding the Arabs from volunteering. Are we not also demanding freedom and democracy? Would not the Arab Maghreb be able to achieve its national freedom if the fascist generals were defeated? Would the defeat of the Italian fascist forces at the hands of the popular democratic Spanish forces not lead to the salvation of Arab Tripoli from the clutches of the tyrant Mussolini? Would the victory of the Spanish Republicans over the German and Italian colonizers not tip the scales in favor of supporters of democracy, and of oppressed people the world over? I did not hesitate, and in a matter of days I was on my way to Spain.

In this context, Palestinian Arabs’ willingness to sacrifice their lives reflects an underlying cultural belief in martyrdom as an act of agency and a path to eternalize a superior cause—that is, the liberation from the oppressor. In Palestine’s case, it shows the longing to perpetuate “Palestinian land that will never die.” The novel tells a story of dual self-sacrifice. On one hand, the Palestinian martyr’s blood mixing with the land testifies to the Palestinian claims to that land in the face of its confiscation. On the other, Ali’s concurrent journey to Spain embodies this self-sacrifice. In both journeys, the narrator glorifies the “prestigious honor of martyrs who fall while defending the land” and dubs them “heroes who have reached eternity,” whose “blood does not flow in vain” and whose power resides in the reward or “diyya,” that is, a free nation.

In this context, Palestinian Arabs’ willingness to sacrifice their lives reflects an underlying cultural belief in martyrdom as an act of agency and a path to eternalize a superior cause—that is, the liberation from the oppressor. In Palestine’s case, it shows the longing to perpetuate “Palestinian land that will never die.” The novel tells a story of dual self-sacrifice. On one hand, the Palestinian martyr’s blood mixing with the land testifies to the Palestinian claims to that land in the face of its confiscation. On the other, Ali’s concurrent journey to Spain embodies this self-sacrifice. In both journeys, the narrator glorifies the “prestigious honor of martyrs who fall while defending the land” and dubs them “heroes who have reached eternity,” whose “blood does not flow in vain” and whose power resides in the reward or “diyya,” that is, a free nation.

As the novel frames Ali’s journey to defend Spanish freedom as an extension of Palestinian Arab resistance at home, it sheds light on the turbulent history and the political and social contexts of pre-1948 Mandatory Palestine. In the opening scene, Ali sets sail to Spain while having flashbacks of Jerusalem’s holiness tarnished with violence, Jaffa’s shamouti oranges, and Haifa’s shores. The scene alludes to a string of protests in 1933—in Jerusalem on October 13, Jaffa and Nablus on October 27, and Haifa on October 27 and 28—that reflected intensifying activism against British rule and its anti-Arab policies, notably the Balfour Declaration (1917), which supported the Zionist movement’s call for a Jewish national home in Palestine. The Declaration legitimized the increasing number of Jewish settlements, which had begun in the nineteenth century and turned into organized Jewish immigration to Palestine, provoking strikes and tensions between Palestinian Arabs and Jews during this period. A series of revolts against the Jews of Palestine in the 1920s ensued, with clashes erupting in between Jewish and Arab communities over control of the holy sites. This explains Ali’s mourning of the “repeated crime” in Jerusalem, recalling Jesus’s crucifixion in Golgotha. Notwithstanding Ali’s upbringing as a fellah who lost his land to the Zionists, the novel’s focus on Jerusalem, Jaffa, and Haifa shores up the city as the center of class struggle, cultural awareness, and resistance, in a parallel with the combat in Madrid.

Nonetheless, the fact that the eruption of the Palestinian Arab Revolt in 1936 coincided with the beginning of the Spanish Civil War raises questions on the reasons for the Palestinian Arabs’ decision to fight in Spain rather than in their homeland. Surely, Ali’s unhesitant response to this question—“every arena of struggle is an arena of honor, and the current arena of struggle is in Spain”—expresses solidarity with the Spanish cause. Yet a closer look at the volunteers’ involvement in the PCP and its evolving policies in response to local instabilities helps explain why they viewed fascism as a threat to the Palestinian cause.

Palestinian Arab communists witnessed the shift of the Party, originally conceived as predominantly Jewish, from being concerned with social class disparities to its adoption of a national liberation strategy, demanding that Jewish laborers help dispossessed Palestinians “expel Jewish settlers who took over their land,” as Ran Greenstein writes in a 2009 article in International Labor and Working-Class History. While the 1929 clashes led the Communist International to call on the PCP for more inclusiveness of the Palestinian Arab working class, the Party later adopted its Arabization policy in response to the eruption of the Arab Revolt (1936-1939) against the increasing influx of Jewish immigration from an increasingly anti-Semitic Europe. As a result, the party recruited more members from the Palestinian-Arab community while its Jewish membership decreased.

In the novel, Ali’s political outcry at British colonialism and its “divide and rule” policy underpins his discontent with the Yishuv, the pre-Israel Jewish community established in the 1920s by the PCP, which the narrator dubs the “deceiving pre-Nakba Jewish community in Palestine.” As Yassin told me, it was a “non-nationalist party that served the colonizers’ interests.” The Palestinian Arabs, in other words, saw the British and Zionist forces as manifestations of the same fascism that the Spanish Republic was battling. This explains what motivated Palestinian Arabs like Ali to join the PCP and travel to Russia, back to Palestine, and then to Spain while the Arab Revolt was igniting in Palestine.

Palestinian Arabs saw the Yishuv as a colonialist project aimed at forcing a new Jewish state on the indigenous population. Yet in the novel, Ali’s romantic involvement with Jewish women of the PCP changes his perspective and help him discern the shared struggle of many Jewish immigrants against injustice, Zionism, and British imperialism. His first sexual encounter with Samha, a Yemenite Mizrahi communist activist who escaped Yemen with her mother, for example, is an epiphany that delineates his views on “the power of freedom, emancipation from the past, […] social justice, and gender equality.” Samha also recounts the story of Alejandra, a Spanish Jewish communist who had joined a Kibbutz and was later killed by the British Intelligence for speaking against injustices against Palestinian Arabs and the false myth of a vacant land. To Yassin, her story, too, bridges the Palestinian and Spanish struggle for liberation, a link that he is keen on portraying throughout Ali’s journey.

Nevine Abraham is Assistant Teaching Professor of Arabic Studies at Carnegie Mellon University. She has published on Arab and Coptic citizenship, identity politics, cinematic representation, and the politics of food. Hussein Yassin is a Palestinian novelist who was born in the village of Arrabeh in Upper Galilee in 1943, received his Bachelor’s in Economics at the University of Leningrad, Russia in 1973 and currently lives in Jerusalem since 1984. Ali: The Story of an Honorable Man (2017) was published in Arabic, was long-listed for the Arabic Booker Prize, and has been translated into Spanish. All references to the novel in this essay are to the Arabic version and all translations from the Arabic are the author’s.