Spanish Diary by Dutch Resistance Hero Discovered

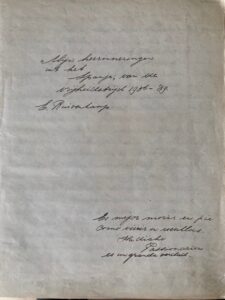

When 93-year-old Rosa Ruivenkamp died in 2019, in her nightstand her son found a blue notebook that had belonged to her brother Evert, who had been active in the resistance and was murdered by the Nazis in 1943. The notebook—which, fortunately was not thrown out—turned out to contain the diary notes Evert had written as a member of the International Brigades in Spain, and which he’d elaborate on in the years following. The text has now been published in the Netherlands.

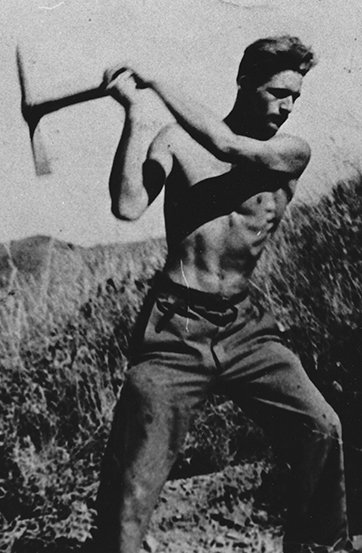

Evert Ruivenkamp was born in Philadelphia in September 1915. His adventurous mother had followed the anarchist Willem van Eck to the United States, but the relationship did not last and in 1916—when she was about to give birth to her second son—she traveled back to Europe. She settled in The Hague and married Rinke Ruivenkamp, a carpenter who, like her, was active in the trade union movement. Life-long leftists, they named their two daughters (born in 1926 and 1929) after Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht: Rosa Karla and Karla Rosa.

After Hitler’s rise to power in 1933, numerous German anti-fascists sought refuge in the Netherlands, where they were taken in by the International Red Aid and placed with Dutch families. Many Dutch volunteers who left for Spain after the outbreak of the war there in 1936, reported that the stories of the German refugees had given them a clear picture of fascism and strengthened their conviction that it had to be fought in Spain too. Many Germans IBers left for Spain from the Netherlands as well.

Evert, who was active in the International Red Aid in The Hague, became friends with Willi Rentmeister, a German communist and Jew who had fled to the Netherlands in 1933. In his diary, Evert writes that he had wanted to leave for Spain as early as November 1936, together with Willi and a group of German volunteers, but his parents begged him not to go.

When he finally decides to join the fight Spain, in March 1938, he keeps his parents in the dark. He’s never been abroad. Since the French-Spanish border is closed, he crosses the Pyrenees clandestinely with a group of 40 men and a Spanish guide, and almost drops to his death in one of the deep ravines.

Every few days, Evert writes in his diary. The text is unadorned, honest, sometimes cheerful, sometimes sad or furious, averse to ideological polish. He has only just arrived in Spain when fascist troops advance on the Mediterranean and Republican Spain is split in two. In his notes of April 14, 1938—the seventh anniversary of the Second Republic—he describes how the international troops are being moved from Albacete, where the headquarters of the International Brigades is housed, to Catalonia. The bridge over the Ebro is already badly damaged, the railroad line is under constant bombardment, the town of Tarragona is a smoking mess, and he sees how just before Franco’s advancing troops move out, the seriously injured are moved north to hospitals in Barcelona and the rest of Catalonia.

At the training camp in Vila-Seca, near Tarragona, Evert reunited with his friend Willi Rentmeister, who served in the company commanded by Wil de Lathouder. De Lathouder—who had left for Spain in September 1936, the first Dutchman to do so—had been badly wounded shortly after his arrival and fallen in love with the Spanish nurse Rosario Plana Sole. The two married and in March 1938 their son was born. A few months later, De Lathouder was killed in the battle of the Ebro. Once back in the Netherlands, Evert took care of Rosario, who had managed to escape from Spain with her son.

Evert’s baptism of fire at the front would come in the summer of 1938, but in the first months before moment he led a relatively quiet life. He was billeted in the small village of Villela Alta together with Rentmeister, who—as he teasingly writes—is constantly in love. The truth is that Evert, too, has an eye for the nice Spanish girls, but he is also deeply affected by the stories of the refugees from the fascist zone who have taken up residence in Vilella. He then falls deeply in love with an American nurse he calls Lilian (but whose identity, unfortunately, remains unknown). She is killed in a bombing in August ‘38.

Once the Ebro offensive is under way, Evert is fully involved. He writes:

The real misery of war is not easy to describe. Greater minds than mine have only partly succeeded in doing so. Ludwig Renn, for example, one of our commanders and a well-known German writer, once told me that even the most suggestive scene in a single one of his books only gave a very faint picture of reality. And even then, no one would believe it. Of course it is almost unbelievable, so much inhumanity. One must first have experienced it to judge.

After some initial successes, the Ebro offensive ends with defeat for the Republic. When, in a desperate attempt to end the large-scale German and Italian intervention, the Republic decides in October 1938 to withdraw the International Brigades, Evert is stunned and deeply unhappy. He writes:

Salut hermanos voluntarios hasta pronto. Brothers they called us. Yes, brothers, that is how we all felt. For the last time we stood before the battalion. José said goodbye to all those who were standing there. We are united in our victories and united in our losses. He embraces me. Neither of us can say a word. Tears run down his cheeks. I cannot push them back either. Like little boys we stand there. “Salut camarada hermano,” he says. See you soon. The belief in a free Spanish Republic is not dead.

Then, Evert recalls the opening line of Jan Oudegeest’s well-known Socialist anthem: “Some time, a clean clear day will come…!”

The diary ends rather abruptly. There is no further description of the journey back to the Netherlands, which is surprising. Evert had every reason to write about it and to express his indignation about the treatment that awaited the Dutch Spaniards in the Netherlands. They lost their nationality and Evert, together with six other Spanish combatants, was tried by a court in The Hague. The trial was a dud, but the Dutch intelligence service drew up a list of “subversives” in 1939, which included all the Dutch IB volunteers. After the German occupation of the Netherlands in May 1940, the list ended up in the hands of the Gestapo. Countless Dutch “Spanjestrijders” ended up in German concentration camps. Possibly Evert was still rewriting his diary from Spain when he was arrested in 1943—which would explain why it was left unfinished.

In December 1940, Evert was married to Rosario, the widowed nurse. By then he was already engaged in the resistance, despite the dubious attitude of the Dutch Communist Party, which took an unequivocal stand only after the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Evert was arrested in February 1943, tortured and, after a show trial, executed.

How his diary survived the war and where it has remained all these years is not clear. Possibly Rosario kept it and entrusted it to Evert’s sister Rosa at the end of her life when she decided to return to her native town in Catalonia. The family tells us that Rosario—a widow of two Dutch IB volunteers—never wanted to speak a word about the past.

In the diary the family also found a letter, dated in 1939, from Evert’s friend Willi Rentmeister, who at that moment he was interned in the concentration camp at Argelès in the south of France. The German volunteers, of course, could not return to Germany after the dissolution of the International Brigades. Many were locked up—often under miserable conditions—in French camps. Many, including Rentmeister, were later deported to Nazi camps. Miraculously, he survived. He died in 1997. A Stolperstein—a brass commemorative cobblestone—was laid down for him in his hometown of Sterkrade, north of Duisburg, in 2016.

In the 1939 letter to Evert, he wrote prophetic words:

I was very happy to read that you have decided to continue to fight relentlessly against cruel fascism until the whole world is liberated. My friend, I am convinced that you will do exactly that.

Yvonne Scholten is a Dutch writer and freelance journalist who has worked as a foreign correspondent in Italy and other countries. She has written biographies of Fanny Schoonheyt and Bart van der Schelling, who both fought in the Spanish Civil War, and has coordinated the online biographical dictionary of Dutch volunteers in Spain at www.spanjestrijders.nl. Her edition of Ruivenkamp’s Spanish diary, Een Hollandse jongen aan de Ebro, is out in the Netherlands. English version by Sebastiaan Faber.