In Search of the First Dutch Volunteer

Willy de Lathouder was the first Dutchman to join the defense of the Spanish Republic. He died in 1938 shortly after the birth of his child. More than 80 years later, his granddaughter discovers her family’s history.

“I’d seen a picture of him as a kid. It was kept in a drawer in my grandma’s house, in The Hague. A good-looking man, I thought. But I didn’t know what that thing was that he was holding in his hands. And I had no clue the picture had been taken in Spain. My grandma never said anything about the past. She spoke Spanish, Dutch, and Catalan. She’d always call the supermarket supermercat, in Catalan. That’d make us kids laugh.”

Karla de Lathouder was born in 1979 in Valencia, Spain. During her childhood, her family moved to Germany, the Netherlands, and Chile. Her father worked for a multinational and her mother was Chilean; they’d met in Spain in the 1970s.

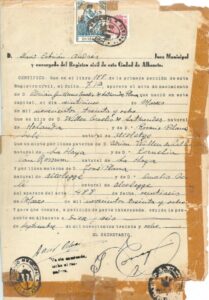

Karla’s father died on his 56th birthday, in 1994, when she was only 13. She never had the chance to ask him the questions that emerged later. Why, for example, he’d been born in Albacete, Spain, in 1938, in the midst of the Spanish Civil War. Her grandmother, Rosario, died seven months after her son. Shortly before, she’d moved back to Spain to live with her family there.

For twenty years, the family past remained a mystery. It isn’t until 2014, when Karla’s still living in Chile, that she begins to research the lives of her father and grandparents and finds her last name, De Lathouder, on the online biographical dictionary of Dutch veterans of the International Brigades, spanjestrijders.nl.

She was stunned to discover that her grandfather, Willem de Lathouder, who goes by Willy, had been the first Dutch volunteer to travel to Spain, shortly after the outbreak of the war. He’d been wounded almost immediately and ended up in the Lérida hospital, where he’d been treated for months by Rosario Plana, a 26-year-old Spanish nurse—Karla’s grandma Rosario. Willy and Rosario got married and briefly visited the Netherlands, only to return to Spain, where Rosario gives birth. Karla’s father was born in Albacete, where the IB headquarters is located. Rosario works in the hospital and Willy has a job in the press office. That summer, Willy returns to the front to join the Dutch company “The Seven Provinces.” Four months after the birth of his son, he’s shot on the Ebro front.

Trying to find out more, Karla gets in touch with me. Over the following month, an extensive correspondence develops among the De Lathouder cousins, who confirm what Karla suspected: grandma Rosario never once spoke about her Spanish past. The wartime traumas must have been too intense. Her life had no room for the past.

After Willy’s death, Rosario and her infant son had moved to The Hague, in Holland, where she’d received help from Willy’s family and friends. Among them is fellow IBer Evert Ruivenkamp, who takes Rosario and Adrián under his wing. After the German invasion in the spring of 1940, he joins the Resistance, along with other veterans from Spain. In December 1940, he and Rosario get married. In October 1942 Evert is involved in an attack on a company that collaborates with the Nazis. The following February he’s arrested and tortured. In June, he’s executed.

Rosario, who lost two husbands in four years’ time, would never remarry. She stayed in The Hague, where she’d eventually run a small bed and breakfast. She has a difficult relationship with her only son, who travels a lot for his job. She doesn’t see him or his family very often. Still, she gets along with her Chilean daughter-in-law, Karla’s mother. Yet by the time Karla gets interested in her family history, her mother’s suffered a heavy accident that’s blown a hole in her memory.

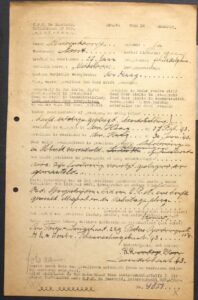

Two years ago, Karla and her mother moved to Murcia, in southern Spain. In October 2021, I met up with her to visit the region where her grandfather fought alongside his friend Evert Ruivenkamp and where he was killed. Ruivenkamp’s Spanish Civil War diary, which has miraculously survived, kept us company. (The diary will be published this year in the Netherlands.) “I feel like I have two grandfathers,” Karla told me. “It’s so sad that I never got to meet them.”

All we know about her grandfather’s death is that he was killed somewhere near Gandesa. “I’ll never see Willy de Lathouder again,” Evert would write in his diary:

Theo told me he fell near Gandesa. One person says he was shot in the head. The other, that it was in the stomach. Either way, his life is gone. Worst off is his wife, whose baby must not be older than six months. They’re all dying, one by one. When will it be my turn?

The Theo mentioned is Theo van Reemst, a medical doctor whom Evert admires deeply, and who’s continued working in the improvised small hospital in the train tunnel at Ascò, even though he’s running a fever of 102. Other train tunnels have been turned into hospitals, too, as have the caves in the nearby mountains—they only places offering some kind of protection against the constant bombardments from the German and Italian air force.

Today, the Ebro region is home to museums large and small. Signs all over point to small monuments and memorials. The memory of the war is more present in Catalonia than elsewhere in Spain. There’s also more government support for exhuming the many mass graves—initiatives that often face bureaucratic resistance in other regions. Some very recent exhumations near Gandesa have recovered 177 remains, we are told by Jordi Martí, who works for office of Democracy Memory of the Catalan government. Karla’s dad may well be among them, he suggests. Karla leaves a DNA sample for a possible future identification.

As we travel the region, we visit museums in Gandesa, Corbera d’Ebre—which was bombarded almost as intensely as Guernica—and La Fatarella, which features a photography exhibit dedicated to the International Brigades. We also meet with a local historian, Josep Munté i Mateu, who’s researched the IB presence in the area and says he knows two places where Dutch volunteers were buried. He seems to know every square inch of the region like the back of his hand. Yet he’s doubtful that Karla’s grandfather is among the recently recovered remains. Evert Ruivenkamp’s note that he died “near Gandesa” is much too vague, Munté tells us. Couldn’t we tell him anything more specific?

Here my own years of research on the Dutch volunteers in Spain proved useful. I’d first run into Willy Lathouder in a booklet published in 1939 by the Dutch Communist Gerard Vanter (whose real name was Gerard van het Reve, and whose two sons would become well-known writers after the war). The precision of Vanter’s testimony seems to suggest he witnessed the facts himself.

On the morning of July 28, 1938, the Dutch company is ordered to take a hill:

There’s heavy fighting around the small town of Corbera. Early in the morning, the company must take a position to the right of Corbera, Hill 460. … So we march promptly. … It’s time to take the hill. Get the mortars ready. Leave our luggage behind. Just hand grenades and rifles. The machine guns are giving us cover … Listen for the sign to attack: a long, vibrating whistle. … But then, while we’re almost done preparing, massive shooting breaks out. “Damn it!” Piet curses. We’re under fire from all sides. The fascists are attacking. A total surprise attack from the enemy. One moment the men are stunned, disoriented. Then Kurt Lauber and Hollander Piet both shout: “The Seven Provinces Don’t Back Down!” Machine guns rattle, mortars blow, hand grenades fly. The enemy retreats, but the fight is a bloody one. Lathouder falls. So do Polak, IJzendoorn. … In a half hour, we count eight dead and 33 wounded.

When I share this information with Josep Munté, he jumps up at the mention of Hill 460. Not only does he know all the hills in the area, but he also has maps that show the precise trajectories of the Republican army units during those days. Munté takes us to Hill 460 and explains that the attack described by Vanter must have occurred between Hills 460 and 442. And then he points to the field where, he tells us, Karla’s grandfather was shot.

Karla takes a moment for herself, walking silently around the field. Josep and I walk back to Hill 460. “Look,” he says, breaking the silence. He squats and, with his index finger, digs up a piece of metal. “A shell fragment,” he says, deadpan. “Look,” he says again, as he digs up more pieces. Grenades. These hills still hold thousands of pounds of scrap metal. It’s only now that the sheer magnitude of the Spanish Civil War hits home. A rehearsal for the Second World War, indeed.

Here’s Karla’s testimony:

I remember growing up, being very aware that my family story was quite unique and different from any other. I had a South American mother and a European father, Chilean and Dutch, and my sister and I were born in Valencia, Spain. No one could ever really understand this. But for me, it was just my story, my heritage.

I never wondered why my dad spoke perfect Spanish—we Dutchies usually speak many languages. Hearing Spanish, Dutch and German was normal to me. When we lived in the Netherlands, my family and I would sometimes drive up to The Hague, to visit my grandmother Rosario. She was a very peculiar character. Blind, skinny, and small, she spoke a kind of Spanish I did not completely understand. (Now I know it was Catalan.) She worked as a nurse while she was young, just like my other grandmother. She was always very happy to see us and host us at her house, but she was not the kind of grandmother who would hug or tell her grandchildren bedtime stories—or any stories at all. She always looked tired and would never speak about her past. My dad was the only person that really brought joy to her. And I guess we, her granddaughters, did too.

After my father’s death, my mother, now a widow in a foreign country, returned to Chile to be closer to her family. I was 15 when I left the Netherlands. My dad had been my best friend. He taught me so much about life and how the world works. I felt I was leaving behind everything that linked me to him.

Fast forward to 2018. I had started wondering about other de Lathouders in the world—my father was an only child—and reconnected with his cousin Ludo, who knew tons of our family history and generously shared his stories with me.

One day, I entered “de Lathouder” into the Google search bar and was stunned to see the name linked to the International Brigades. What is this purple, yellow and red colored flag? I read that the headquarters of the International Brigades was the town of Albacete, Spain. Then it dawns on me: “That’s where my father was born!” I’m at a loss. I knew my father grew up during World War II, in Holland. What’s the link to the Spanish civil war? When did he die? The date of his death connects him to the Battle of the Ebro period.

I slowly begin to realize that my grandfather Willy was a Dutch soldier in the International Brigades who had met my grandmother Rosario, a Catalan nurse, when he was wounded in battle. I finally understand my family’s history—my own history. Still, there are gaps. Where is my grandfather now? I feel I need to find him. I need to close this story.

In 2019, I move back to Spain, and soon after I’m contacted by a Dutch journalist, Yvonne Scholten, who is editing Evert Ruivenkamp’s Spanish Civil War diary, which mentions my grandfather. We begin sharing information with each other by email. Then in 2021, despite the Covid restrictions, Yvonne and I manage to visit Terra Alta in Catalonia.

What can I say? I feel humble and grateful. Knowing my history has given me peace of mind, it has made me more empathic with my grandparents’ generation. Being so young and surviving not one, but two wars is quite an achievement. I am very proud of being a part—and, in a way, a result—of this brave love story.

Yvonne Scholten is a Dutch writer and freelance journalist who has worked as a foreign correspondent in Italy and other countries. She has written biographies of Fanny Schoonheyt and Bart van der Schelling, who both fought in the Spanish Civil War, and has coordinated the online biographical dictionary of Dutch volunteers in Spain at www.spanjestrijders.nl. Her edition of Ruivenkamp’s Spanish diary is forthcoming. English version by Sebastiaan Faber.

Thanks , Danke , Gracias. He was one of the first defenders of democracy en Europa against fascism. Siempre presente. Nunca te olvidamos.

Thank you so much for sharing this article. It was really a heartwarming experience to be able to retrieve my family history, knowing that during my fathers life, this research would have been absolutely impossible. I kindly want to thank Yvonne Scholten for all her wisdom and support, Josep Munté for his uncomparable knowledge of the Ebro battle, and of cpurse the Generalitat de Catalunya for their non stop commitment in matching the victims with their families so we all can have some peace. I hope my story inspires other people, in my same situation, to pursue their history.

In loving memory of Willy, Evert, Rosario and my dad Willy.