The International Brigades in Color

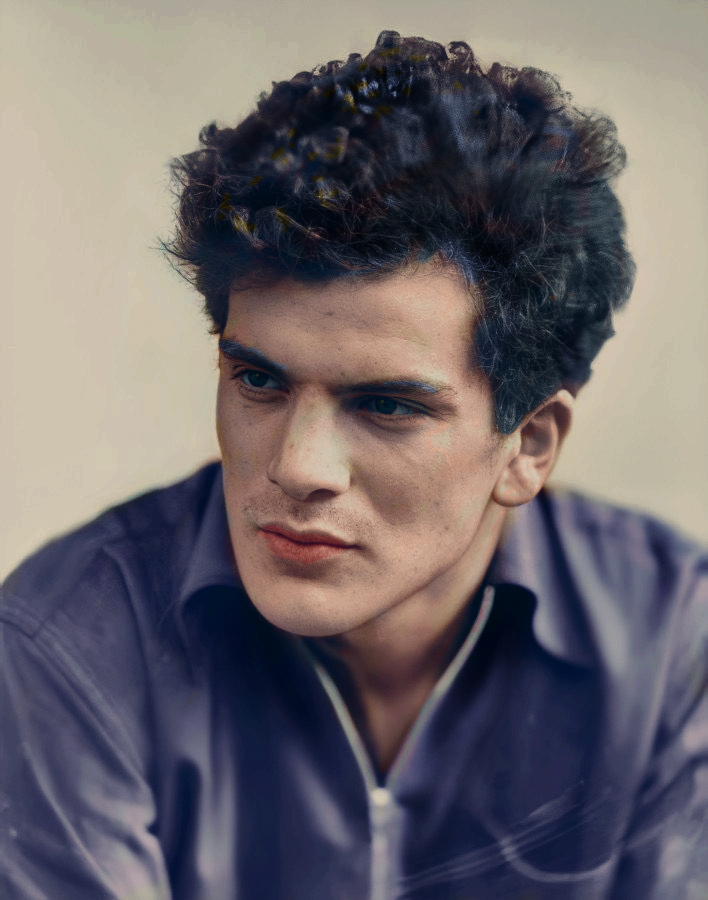

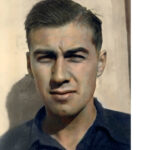

Luchelle McDaniels. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0127. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

The Memory of the Past Occurs in the Present: On Tina Paterson’s Colorized Portraits

By Francesc Torres

When a friend first pointed me to Tina Paterson’s colorized portraits of International Brigade volunteers, I was skeptical. Yet the images are disturbing and strangely powerful. Throwing time out of joint, they undermine the idea that the Civil War is a remote historical occurrence.

Some years ago, while working on Dark Is the Room Where We Sleep—a project in which I photographed the exhumation of a mass grave from September 1936, with 46 civilian victims, at Vilamayor de los Montes in Burgos—I was struck by a sudden revelation: Although I was born nine years after the end of the Civil War, I am a clinically pure product of that disastrous historical event, which signaled the end of the only moment in the twentieth century—the five years of the Second Republic—in which Spain found itself on the decent side of things.

All of us, of course, are a product of the past and of History with a capital H. But not all in the same way. Speaking for myself, the realization that the most fundamentally determining factor of my life had occurred almost a decade before my birth made me furious, although it also helped explain many things that until then had been unclear to me.

I was furious because I felt it was extremely unfair. It’s one thing to live a particular historical moment and to have the opportunity to intervene, to help determine its outcome in some way. Even if you end up losing, the fact that you did not stand by passively can be a source of pride. Not having had that opportunity, however, made me feel cheated. Worse, I felt I’d been defeated without ever having had the chance to defend myself.

Here I should point out that my grandparents were persecuted by the Franco regime. I now understand that my work, which has returned to the Spanish war time and again, has been an attempt to fuse the emotional intensity of my own family history with the historical event that shaped it. What I’ve tried to do, I think, is to eliminate that decade of historical distance and make the war physically, literally mine. Of course, it’s an aspiration that’s bound to fail. What it reflects, nonetheless, is the need for some kind of symbolic mediation. To satisfy that need, art—visual or literary—can be an efficient tool.

Several weeks ago, a friend on Facebook pointed me to a set of colorized photographs of International Brigade volunteers. Originally shot in black and white by the great Harry Randall, these portraits are part of the ALBA collection at NYU’s Tamiment library. They were colorized by a Madrid-based artist who goes by the name of Tina Paterson. Over the days that followed, I began posting the images to my wall. To my surprise, they sparked forceful reactions.

Harry Randall. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0932. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

I must confess that I was skeptical at first. To be sure, there are early color photographs going back as far as World War I. Yet the visual history of the first half of the twentieth century has largely come to us in black and white. It’s that monochromatic varnish that gives that part of history its authenticity, so to speak. Until the appearance of digital processing, a colorized photograph was simply a black-and-white image retouched with color paint, more or less successfully—mostly the latter. Not something to take seriously.

Yet Tina Paterson’s work is different. Its quality is evident, for example, in the portrait of Rupert John Cornford, the British volunteer who was a poet and grandson of Darwin and who fought first with the POUM and then with the IB’s Dumont Battalion in Aragón and defending Madrid. He died at Lopera (Jaén) on December 28, 1936. What makes his colorized portrait so powerful is that you don’t “see” the coloration. The image’s patina is of the present, not of the past. It appears to be a photograph shot today. Looking at the image, it’s as if we’d been chatting with Cornford over drinks just last night. That gives it a quality I can only describe as disturbing.

William Digges. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0944. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

Aaron Lopoff. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0149. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

Something very similar occurs in the portraits of Williams Mitchell Digges, a lieutenant in the XV Brigade who was born in New Orleans and who died under vague circumstances in 1938, and of Caroline Bunjes-Rosenthal (1918-2016), a Dutch IBer and photographer known as Lini, who fought in the “Joven Guardia” Battalion. Eighteen years old in November 1936, she poses for the camera—not Harry Randall’s this time, but Hans Guttmann’s—with her arm in a sling, recovering from an injury. Then there’s the portrait of Aaron Lopoff (1914-1938), a Jewish-American writer who arrived in Spain in 1937 to join the Lincoln-Washington Battalion, where he made company commander. He fell in battle in September 1938, during the Battle of the Ebro.

Robert Merriman. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0634. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

The portrait of Robert Merriman stands in a different category, at least for me. I’ve been fascinated with Merriman ever since I learned about him many years ago, reading his wife Marion’s memoir. In 2018, I agreed to serve as staff photographer on a fieldwork project organized by historians of the University of Barcelona who went in search of Robert’s body, which was said to have been buried on private land in Corbera d’Ebre, in the Tarragona province, nearby the Ebro battlefront.

Merriman disappeared in 1938, while serving as the Lincoln Battalion’s commander. His death has always been shrouded in mystery. The most recent version of the story claims that Merriman, while retreating in precarious circumstances from the Segre front along with some fellow soldiers, had the misfortune of running into a Francoist army unit. According to this account, Merriman would have been taken to Corbera for interrogation, only to be shot a couple of hours later, in his underwear. What would have happened to the other soldiers is unclear.

The researchers on the team had done their homework. In fact, they seemed to have hit on an unprecedented piece of evidence: nothing less than an eyewitness account. An old man who had been sixteen at the time said he’d been forced to bury Merriman. And what’s more, he remembered where. Yet as happens so often, neither the geo-radar scan nor excavating a broad area yielded any results. We literally found nothing—nothing at all. This was strange. Since the area had been a battle zone, we expected to run into sediments of all kinds. Yet all we found were pieces of Roman ceramics—not a single machine-gun or rifle bullet. This suggested that, at some point in the past, the area had been carefully cleaned up. I shuddered at the thought that all the human remains here had been systematically cleared in the 1960s, when Franco ordered victims’ bodies from all over the country to be transported to the Valley of the Fallen. The mere idea that Merriman’s bones could have ended up there (something we’ll never know) was almost too hard to bear.

Today, recalling that experience in the face of the radical immediacy of Harry Randall’s portrait of Merriman, colorized eighty years later by Tina Paterson, throws time out of joint. Past and present overlap into a single emotional frame, at once inside and outside of historical, diachronic time. The frame that emerges instead is synchronous. It belongs to a time that’s not circular but spheric, without beginning or end, mythological. Here, then, is the paradox: an image from the past that seems to be from the present lifts us out of history to plunge us in myth. It’s extraordinary.

This, I think, is the virtue of Tina Paterson’s best work. The images directly undermine the perception that the Civil War—the most important event in twentieth-century Spanish history—is a remote historical occurrence. They belie the official, distorted narrative that claims that the war no longer has any bearing on the country’s normalized, democratic presence. The truth is, of course, that the war continues to loom large in Spain’s social fabric. Even Spanish politics is still divided along the same ideological paradigms of the 1930s, albeit in a postmodern guise.

In fact, it’s profoundly revealing that the solution to Spain’s monumental problem has been left to biology—to the hope that, with the gradual death of those who lived the war and the immediate postwar years, there will be no one left to ask questions, to demand historical or political accountability, to make clear that it’s not true that “we all carry some blame,” as the new democrats on the right like to claim.

Yet some of us are still around. People like me, old as we may be, continue to be indignant, up in arms, over the fact that something we did not live shaped us, made us who we are.

Francesc Torres, born in Barcelona in 1948, is a New-York-based visual media and installation artist whose work has been featured in museums around the world. His books include Memory Remains: 9/11 Artifacts at Hangar 17 (2011) and Dark is the Room Where We Sleep (2007). Translation by Sebastiaan Faber.

- Milton Wolff. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0631. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Samuel Willis. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-1280. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Wen Rao. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0924. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Elkan Wendkos. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0612. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Fundraiser for the VALB. Photo Tina Paterson.

- Joseph Taylor. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0167. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Clyde Taylor. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0009. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- ALB Volunteers ont he SS Harding. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Fanny Schoonheyt. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Lincoln Brigade Veterans, May Day in New York City. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Oliver Law. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Jef Last. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Salaria Kea. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Ivor Hickman. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Irene Goldin. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0841. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Philip Detro and Leonard Lamb. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0713. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- Alvah Bessie. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA PHOTO 11-0176. Tamiment Library, NYU. Color by Tina Paterson.

- William Aalto. Color by Tina Paterson.

Great toi see this,