Exhuming Injustice: A Mass Grave in Manzanares

When people think about mass graves in Spain, most relate them to the war years. Yet an estimated 50,000 victims were executed after the war. This summer, I visited a cemetery where the ARMH are exhuming the remains of some of these victims.

“I often remind my 91-year-old mother to hang on a bit longer and not to go yet because her two uncles will be unearthed soon,” a tearful Manuel Gallego told me on July 5, 2021 in Manzanares (Ciudad Real, Spain). This past May, the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARMH in Spanish) exhumed 34 of 288 victims of Franco’s regime from two mass graves in the town’s cemetery.

When people think about mass graves in Spain, most relate them to the war years. Yet an estimated 50,000 victims were executed after the war. Walking around the dry and desolate terrain of the Manzanares cemetery, one is reminded of what Franco said shortly after the war: “Those whose hands are not stained with blood will have nothing to fear.” The victims in this cemetery are here because they made the mistake of believing those words. Executed before the cemetery walls between 1939 and 1940, they were buried in two distinct areas: 14 mass graves within the cemetery (reserved for those who were administered the last rites) and two outside of its walls (for those who refused). The bodies that were recently exhumed belonged to this latter group. It was not until the 1980s that the original wall dividing the secular from the religious cemetery was finally torn down. The victims are from Manzanares and other small towns in the area. Sentenced to death in cynical show trials, they were found guilty of adhesión a la rebelión (support of the rebellion), the ironic phrase with which the regime described the resistance to Franco’s 1936 revolt against the Republic.

During my visit to the exhumation site, I spoke with several of the victims’ family members, including Pedro Alises Núñez and Inmaculada Camacho Serrano of Memoria Histórica Manzanares (MHM), a local nonprofit. Inmaculada had arrived that morning after a four-hour car ride from her home in Valencia. They took me to what used to be the outer section of the cemetery (the secular side), where they showed me the recently exhumed mass graves: a small patch of now loose gravel, not much bigger than my living room, where 34 bodies had been piled up callously (most likely dumped from a cart) in two unusually deep ditches—about 20 feet—that made the excavation that much harder. Some of the bodies appeared upside down, but others were lying in a fetal position, leading experts to believe that they were alive when they were thrown into the ditch, trying to protect themselves while being shot from above. (Some Mauser shells were found on site.) Pedro’s grandfather was one of the victims exhumed in May. For several days, Pedro witnessed the bodies being delicately gathered, one bone at a time. He is still awaiting DNA results. Inmaculada’s grandfather may be unearthed sometime in the fall or winter, when the archeologists open the mass graves located in the religious section of the cemetery. They are estimated to contain about 255 bodies.

This recent exhumation finally brought a degree of closure to the families of these 34 post-war victims. The exhumation process brought about a mixture of anger and sadness, some of the family members told me. Justice will not feel complete until the trials are fully nullified. Last September, the Spanish government approved a draft Law of Democratic Memory that includes such a nullification, although the bill is still awaiting its parliamentary debate and vote. In the meantime, just in the small town of Manzanares alone, at least 255 more republican victims are still waiting to be exhumed. I had the opportunity to interview the family members of five victims. These are their stories:

Pedro Alises Espinosa

Affiliated with the trade union UGT, Pedro actively participated in the collectivization of land and buildings in the area and was elected to the Manzanares town council. During the war, he joined the Republican forces in November of 1936 as a quartermaster sergeant. He was captured at the end of the conflict, executed on July 20, 1939, and dumped in mass grave number 1 outside of the cemetery, together with 30 others. He left five children and a widow, who was forced to pay fines for years after (a common punishment). Pedro was 45 years old when he was killed. Among the volunteers that has helped unearth his remains is his great-grandchild.

Agustín Camacho Fernández

A barber from the town of La Solana (Ciudad Real), he was accused of being affiliated with the socialist party, and for patrolling the streets of his town as a corporal, supposedly killing six nationalists during the war. He was later captured, beaten, and dragged through the town plaza, tied by hands and feet. When his wife found his disfigured body, which was missing pieces of flesh and skin on his back, she fainted and then left him for dead. His granddaughter Inmaculada later discovered that he recovered from his wounds and spent an additional three months in prison. On July 20, 1939, he was executed. His body lies inside the cemetery, in mass grave number 4, together with 13 others. He left a widow and a three-year-old. He was 28 years old when he was killed.

Alfonso Fontiveros Muñoz

A peasant and strong advocate of peasants’ rights, Alfonso was a member of the trade union UGT from 1928 to 1938, but ended up joining the labor union CNT and becoming president of a peasant’s association in the area. Soon after the war, a neighbor denounced him for belonging to CNT, forcing him to flee to Valencia with his two sons, José and Miguel, who were in their twenties. José managed to flee to France, and Miguel somehow ended up in Barcelona. Alfonso was eventually captured in June 1939, and executed on July 20, 1939, together with 23 others. He was 52. His body was exhumed from cemetery’s secular section in May. His son José would stay in Toulouse, where his girlfriend from Manzanares went to meet him. They married there and raised four children.

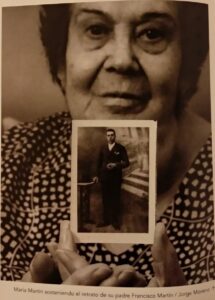

Francisco Martín Carnerero Alcarazo

Recently unearthed together with Pedro’s grandfather, Francisco was a socialist and municipal police officer who belonged to the trade union UGT and participated in several peasant strikes. Because of his job, during the war he detained two nationalists who would later be executed. After the war, Francisco was charged with their deaths. He was also accused of being present during a church burning; however, as a police officer, he was responding to the burning, not participating in it. Contrary to the charges, he was, in fact, helping several nuns escape the church, and brought them to safety. He was imprisoned nonetheless soon after the war ended.

His daughter, María, roughly 10 at the time of his imprisonment, would often bring him food. On one of those visits, she was asked why she came, did she not see the list on the blackboard outside? She climbed on a rock to read the board and realized the names on the list were those of the executed prisoners from the night before. Her dad’s name was on it. In shock, she fell, hit her head, and lost consciousness. He was just 36, leaving a widow and two children. One of his brothers and a brother-in-law also lay in one of the mass graves inside the cemetery. His wife spent seven years in prison for speaking badly about the killers. María, now 91 years old, was recently able to witness the exhumation of her father’s remains, pending DNA results.

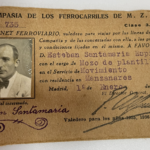

Esteban Santamaría Espinosa

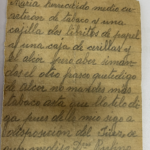

A Manzanares train switchman, Esteban was nicknamed “the train gentleman” because of his habitual fancy attire and tidy appearance. His membership of the town’s “Comité de Defensa” (a leftish and clandestine military organization), caused him to be imprisoned for almost a year right after the war. While in prison, he earned a reputation for helping feed those most in need, including old or sick prisoners who were not given food because their executions were imminent. His granddaughters Rosario and Eva think he must have had some schooling because, despite his frequent misspellings, he expressed himself well and in a very neat manner, as can be seen in the many tiny hidden notes written on cigarette paper that he would pass to his wife during her visits. He was executed in May 1940 together with 19 other prisoners, leaving a widow and three children. He was 36 years old. His body lies in one of the mass graves in the religious side of the cemetery waiting to be exhumed.

***

As I walked out of the cemetery on July 5, I thought of a famous quote from don Luis in the play Las bicicletas son para el Verano (Bicycles are for the Summer), by Fernando Fernán Gómez. Talking to his son at the very end of the war, don Luis warns him: “What has arrived is not peace, but victory.” Manzanares helped me understand the truth of that sentence. Hopefully, some peace will finally come to these victims and their families.

Marimar Huguet-Jerez is an associate professor of Spanish at the College of New Jersey.

- Sisters Eva and Rosario Baeza Santamaría, granddaughters of Esteban Santamaría Espinosa.

- Secular side of cemetery.

- Pedro, Inmaculada and friend at religious side of cemetery (still needs to be exhumed).

- Manzanares mass grave after exhumation was completed.

- Manuel Gallego, grandson of Francisco Martín Carnerero Alcarazo.

- The exhumation.

- Falange insignia at one of Manzanares plazas today.

- Esteban Santamaría Espinosa’s hidden note.

- Esteban Santamaría Espinosa