Never More Alive: Kate Mangan’s Spanish Memoir

One of the most compelling first-person accounts in English from the Spanish Civil War languished in the archives for more than 80 years. Artist and model Kate Mangan (1904-77) was a keen observer of character with a sharp nib on her pen. After traveling to Spain in 1936 in search of her lover, Jan Kurzke, a German refugee who had joined the International Brigades, she ended up working for the Republic’s Press & Censorship office. Her memoir has now been published by the Clapton Press, with the following preface by Paul Preston.

No one knows with absolute certainty how many books have been written about the various aspects of the Spanish Civil War but there is little doubt that they number somewhere in the region of thirty thousand. It goes without saying that the range of quality could not be wider. Academic works abound, of course. There exist many works of unashamed propaganda, a majority of which have emanated from the Francoist side in the conflict, but there is also a substantial minority of partisan works defending Communist, anarchist or other left-wing groups. Then there are the thousands of memoirs, many by politicians and senior military figures who grind their respective axes with varying degrees of honesty and many others by people who experienced the war in some way or other without being a celebrity or wielding power.

It is among these latter “non-celebrity’ memoirs that Kate Mangan’s wonderful book is to be found. I will come right out and say that, ever since I first read the manuscript about fifteen years ago, I have longed to see it in print. I regarded it when I first read it, and ever more so with each subsequent reading, as one of the most valuable and, incidentally, purely enjoyable books about the war. My admiration is a response to the sheer wealth of fascinating information and insight provided in brutally honest yet beautiful prose.

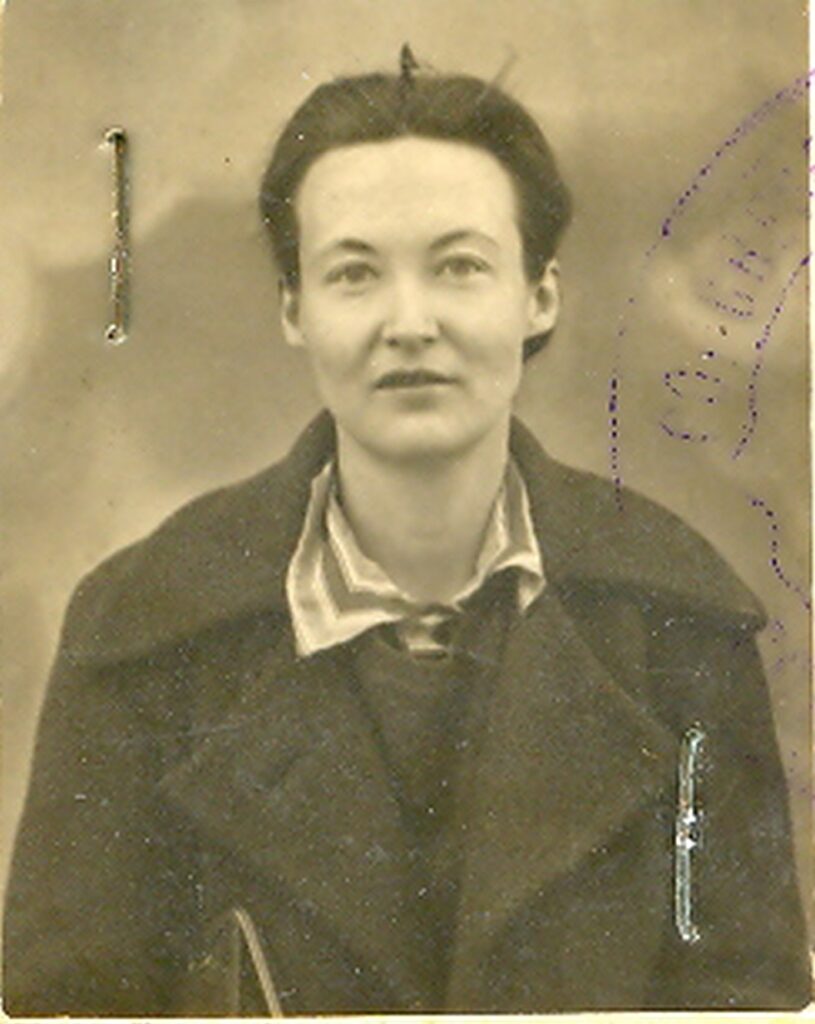

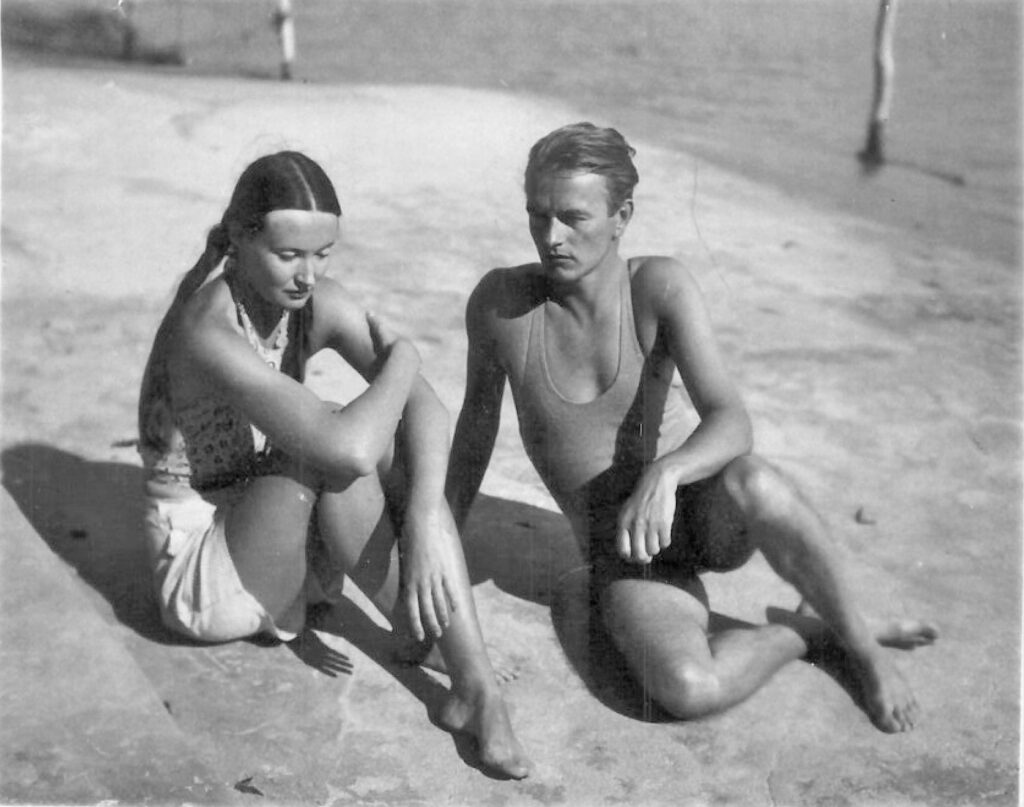

At its core, this is a moving story of the travails of love in wartime, but it is so much more. Born in 1904 as Katherine Prideaux Foster, Kate was an attractive artist who had studied at the Slade School of Art in University College, London, and also worked for a couturier as a mannequin. She was unreservedly left-wing without having a specific party allegiance. In 1931, she had married the Irish- American Marxist novelist Sherry Mangan whom she had met in Paris in 1924 when they were both aged twenty. Partly because of money difficulties but also Sherry’s jealousy of her ability as a writer, they separated in 1934 and divorced the following year. In 1935, she fell in love with Jan Kurzke, a German who had come to London on the run from the Nazis. In late 1935 and the spring of 1936, they spent several idyllic months in Spain and Portugal. In these memoirs, she provides a colorful account of their boat journey to Lisbon and about the poverty and the ubiquitous police presence in Salazar’s Portugal. In the plush resorts of Cascaes and Estoril, she describes the Spanish reactionaries in their gilded exile from the Popular Front: “They were fat and well dressed with big motor cars and numerous polite, befrilled children, servants and foreign governesses . . . the Spanish colony of Portugal is not dead, but flourishes like the green bay tree in all its parasitical uselessness and vulgarity.”

Briefly back in London, she approved of Jan’s precipitate decision to volunteer to fight in the International Brigades despite feeling great concern and trepidation. Eventually, eaten up with worry, she had gone to Spain in October 1936 in the hope of being with him. At first, she picked up casual jobs as an interpreter in Barcelona and then went to Madrid where she acted as secretary to an old friend from London, Humphrey Slater, with whom she had studied at the Slade. Through Slater, she met Tom Wintringham, the senior British Communist who would soon be the commander of the British battalion in the International Brigades, although officially he had come to Spain as a correspondent of the Communist Party of Great Britain’s newspaper, the Daily Worker. Through Humphrey and Tom, she met a “petite and vivacious American girl” called Katherine “Kitty’ Bowler. Kate would eventually find herself sharing a hotel room with her and “swept into the whirl of Kitty’s life.”

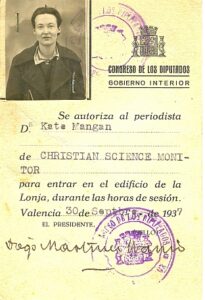

Having located Jan, she could meet him only sporadically. When he was seriously wounded, she threw herself into a desperate search to find where he had been taken, then devoted herself to caring for him and finally to the complex task of getting him released and back to England. In between, thanks to Kitty Bowler, she got a job in the Republic’s press office in Valencia, which had become the capital when the government had left Madrid on 6 November 1936. There, she worked as an interpreter and translator. As a result of her experiences, her perceptions of the political context in which she existed are fascinating.

What she went through to trace Jan and later care for him provides the basis for unique insights into the experiences of an International Brigader both on the front line and behind the lines. Her account of hospital conditions—the lack of drugs and of trained staff, poor hygiene—provides real understanding of the appalling difficulties faced by the Republican medical services. Kate’s is not the only account of the privations suffered by the volunteers—not allowed to go on leave, given poor food, without mail from home, inadequately clad. However, her account sparkles with revealing detail such as how those fighting in the Philosophy and Arts building in Madrid’s University City built barricades of books to protect their machine gun emplacements, then settled down to wait for action: “The scholars read old books in Greek and Latin, for several of the English were from Oxford and Cambridge.”

In fact, the entire book teems with insights into the Spanish Civil War. Her account of her time in the besieged Madrid could hardly be more vivid. As the highest capital city in Europe, winter in Madrid is always bitterly cold. In November 1936, it was worse than usual since coal from the Asturian mines could not reach Madrid. There was almost no central heating or hot water in the hotels.

Kate describes madrileños eschewing their habitually late dinners and eating at 7:30 or 8PM, since bed was about the only warm place in any home, most residents were there by 9. “The cold got into my bones. Nowhere was there any heating and, though I gave up washing and went to bed in most of my clothes, I was never warm and ached and shivered at night so that I could not sleep.” It was so cold that her fingers sometimes froze to her typewriter keys. She recounts having to queue for everything, coal, food, even matches. Yet she never loses her ability to see the funny side of things: “I do not know what went into the bread, possibly rice flour, but it was only just possible to eat it when fresh; within a few hours it became stone-like and would have made a dangerous missile or a solid barricade.” Of the one bar where you could get whisky, she writes wryly: “Here one found journalists, commercial aviators, and whores still clean and fairly smart, though the ones with bleach-blond hair were becoming piebald for lack of peroxide. It was all at the hospitals and plenty of nurses had blond hair.”

In late 1936, she moved to the very different atmosphere of Valencia where the weather was warmer and food relatively abundant. Every bit as compelling as the recollections of Madrid are her recollections of working in the press office. There she came into contact with a gamut of literary celebrities, politicians, secret agents and war reporters—contacts that she describes vividly and often with a wicked sense of humor. Indeed, her memoirs could be plundered by literary biographers for her unique descriptions of the famous literary figures that she met. These include a sneeringly arrogant Claud Cockburn and a painfully shy W.H. Auden whose literary skills are wasted by the press office other than allowing him to make a superb translation of a speech by the Republican President, Manuel Azaña. Kate liked Stephen Spender for his humility and eagerness to help: “He was a very tall, thin young man, with open collar and a leather jacket. He had a rather bony, Viking face and wildly straying hair. He looked red and wind-blown and rather distrait.” She depicted the then world-famous American novelist John Dos Passos as “yellow, small and bespectacled.” He was staying at the Hotel Colón which had been renamed the Casa de Cultura and reserved for visiting intellectuals, artists, and writers. Locally, it was known as the Casa de los Sabios (the house of the wise men) although Kate regarded it as “a kind of zoo for intellectuals.”

Utterly memorable and rather less reverential than conventional views are Kate’s portraits of two celebrity couples, the photographers Robert Capa and Gerda Taro and Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn. Of Capa and Taro, she wrote: “They were a striking-looking couple. He was tall and thin with dead black eyes. She was a ripe beauty, with a tanned face and bright orange hair cropped like a boy’s. The natural tint of her hair was copper, she had the warm brown eyes that go with it, but the sun had bleached it orange and the effect was startling. She was full-bosomed, very handsome but for her head being a bit too large for her height. She wore a little, round, Swiss cap on the back of the astonishing hair. She had small feet and was a model of Parisian sportif chic. She radiated sex-appeal . . . Capa and Gerda talked about Spain and the beautiful sunshine quite as if they were on holiday, which I thought very frivolous, but they did not neglect their work. They were always ready to leap from the car to take significantly grim pictures and were merely personally detached from their subjects.”

She captures precisely the insecurity that underlay the bravado of Hemingway who “always came with a large entourage and always wanted to go to Madrid at once. He was a huge, red man, in hairy speckled tweeds, with a crushing handshake. He looked like a successful businessman which, I suppose, was the impression he wished to make. The first time I saw him, he came with Sidney Franklin, a former bullfighter, and two Dutch cameramen, to make the film Spanish Earth. One always had the feeling that there were several shadowy, unidentifiable, obsequious figures in the background while Hemingway, the great man, was in the foreground.” Martha Gellhorn “was handsome in a rather predatory way, with a beaky nose and brilliant eyes. She had an elegant coiffure, a linen dress and a perfectly even suntan. She wore her skirt rather short, and sat on the table swinging her long, slim legs in a provocative manner. The Spaniards disapproved of this. They believed that sexuality should be directed only at one person at a time, preferably in private.”

Her pages are replete with striking vignettes. Of the two customs men who tried to impede her entry into Barcelona, she writes: “One was small, desiccated, with beady black eyes, lively as a flea; he wore a little forage cap, half red and half black, that made him look as if he came out of a circus. The other one was very pale with a scar, a high-necked jersey and a beret rammed down like a skull-cap; he was much more reminiscent of the French Revolution à la lanterne and as though determined nothing should betray him into a smile.” With equal perceptiveness, she comments of “Valencian farmers who were holding an orange-growers convention. The orange-growers, plump, rosy and steaming, loud-voiced, with big dripping umbrellas, who clustered thickest after lunch, had apparently no consciousness of the war at all. They were only concerned with the difficulties of marketing their produce that year.”

This fits in with her acute comments on the insouciant lack of awareness of the war that she noted in Catalunya both when she first arrived: “At that time in Barcelona, the general public was no more aware of what was going on in Madrid than on the moon.” By the time that she was en route out of Spain with the disabled Jan, in the late summer of 1937, there was little sense of a war going on and one that was likely to be lost: “Very few wounded were about, and Jan was regarded with astonishment and asked about the war as if it had nothing to do with Catalunya. Cafés and restaurants were crowded with young men of military age and smart girls.”

Kate’s job brought her into contact with politicians as well as literary figures. Juan García Oliver, the one-time anarchist gunman who was now the Republic’s Minister of Justice, “lived in our hotel and was a small, high-colored, youngish man with bright blue eyes.” The Socialist Prime Minister, Francisco Largo Caballero “was an old, wrinkled man with pale, shifty blue eyes.” The President Manuel Azaña is accurately depicted as “a short, fat man with a bald head, receding forehead, wire-rimmed spectacles and a large mole on his chin” and perceptively analyzed as being “. . . afraid of doing the wrong thing. . . and did not really want to go on with the war. He was a liberal and would have given up sooner if he had dared.” The attempts of Franz Borkenau, the celebrated Austrian sociologist, to have a sexual liaison with a twenty-year-old university student are behind the portrait of “a dirty old man,” “the professor who was personally greasy and unattractive.” In contrast, Kate pays tribute to the smooth talk of the Comintern’s brilliant propagandist, Otto Katz, the real brains behind the Spanish Press Agency in Paris, the Agence Espagne. His flattery put stiff and rather grand English ladies, the Duchess of Atholl, Eleanor Rathbone and Ellen Wilkinson, entirely at their ease.

Kate did not spend all of her time either in the press office or seeking Jan. She also travelled with London Times correspondent Lawrence Fernsworth and other journalists to investigate the plight of the thousands of refugees fleeing the repression in Málaga along the coast road to Almería. Her grim account of meeting the bedraggled fugitives there is a valuable addition to the important accounts of the tragedy written by Dr. Norman Bethune and T.C. Worsley. Contacts with diplomats yield considerable insight into the anti-Republican attitude of London’s foreign policy. A shocking revelation came from a conversation with the British Vice-Consul in Almería: “We asked him if it was true that British warships were taking supplies into Málaga now that it had fallen to Franco and he said it was. We then asked if any of them were coming up here with food and he said not.” Even more shocking, if hardly surprising, was the remark of another British diplomat about International Brigade volunteers: “I do not see why we should stand in the way of these fellows who come and get killed in Spain. We shall get rid of a lot of undesirables this way.”

Kate’s views on the difficulties of the Republic add to what can be learned from academic studies: “the Spanish Republic was sinking under the weight of the refugees and the problem of feeding so many people. There was little sustaining food to be had. Most of the wheat was grown on the other side of Spain. We had a little rice and, in Catalunya, some potatoes. The fishermen were afraid to go out because of mines. As the Republic shrank in territory, it increased in population, and was much greater than on the other side. Every town and village was swarming with people, women and children, old people, gypsies, all the poorest of the poor, all helpless and without possessions.” So much of what Kate writes about is bleak yet neither the elegance of her prose nor her sense of humor flag. She captures the shambolic improvisation of the popular militias in quoting a remark by her sister Greville: “Oh, we encourage fancy dress in our column,” she said, “it keeps up the morale. Some people wear fur hats like Cossacks, and some big straw ones like Mexicans, and some have feathers like Red Indians.” Her priceless description of the journey from Lisbon back to London in July 1936 includes the comment: “Several of the stewards were actually sailors recovering from appendix operations and thus given over to light duties such as spilling soup over people.” Regarding one extremely serious issue—the opposition to the military coup by the miners in the northern part of the province of Huelva, as recounted by the Portuguese press—she cannot restrain her sense of humor: “The Río Tinto miners were described as having joined forces with the workers in a sausage factory and armed with sausages and sticks of dynamite, were said to be running about in trucks terrorizing the countryside.”

Beyond the specifics of the press office and the hospitals, Kate also captures something important about the spirit of the Republican war effort. Despite overwhelming odds against them, millions of ordinary Spaniards went on fighting to defend the Republic that had given them educational opportunities, women’s rights, and social reforms. Kate, even as a foreigner, present only for one year of the war, seems to have felt this. She writes: “All through the war, one had a wonderful feeling of freedom from the responsibility and individual worries of ordinary life. Once I got used to it, I never worried any more about possessions, or money, or when I would get anywhere, or where the next meal was coming from. Possessions did not seem to matter; I had very few with me but nothing I clung to except my typewriter.” That sense of exhilaration seems not to have survived the difficulties that she faced in getting Jan back to England. When they reached Paris, she reflected, in what was a terrible epitaph for Jan and the International Brigades as a whole: “Jan had done something which a few people thought heroic, to which many Spaniards were indifferent, and which had to be hidden, like a crime, in the country to which he returned.”

Paul Preston, Emeritus Professor at the London School of Economics, is the author, most recently, of A People Betrayed: A History of Corruption, Political Incompetence and Social Division in Modern Spain (Liveright). To order the book from the Clapton Press, click here.

It’s wonderful to see this piece by such an important scholar, but I wish there were footnotes to indicate sources about Kate’s life. I corresponded with her (and her daughter) about her first marriage to Sherry Mangan, an important figure in the Trotskyist Fourth International (who also produced journalism and poetry about Spain that has been reprinted). There was no hint that she (or he) was political at that time (they divorced in 1934). Mangan did publish one novel, a Ronald Firbank imitation, but he was certainly no “Marxist novelist.” (He was a promising poet and minor short story writer, and then, after becoming a Marxist, most famous as a journalist for Time/Life/Fortune.) Money issues were a problem in the marriage and she didn’t like Mangan’s idea of living in Lynn, Ma. with his parents. (London, and Paris where they actually met, was a bit more interesting.) I also had the impression that she met Jan K,. before the divorce at the time she traveled alone to England on a vacation, and this may have been a factor. She and Sherry stayed in touch, corresponding; after her relationship Jan ended, she she visited him in Rome where he was editing the Fourth International journal as “Patrick O’Daniel.”

[…] absence from the book only becomes clear if you have read the account written by his girlfriend, Kate Mangan (and I strongly recommend that you do). She was with him in Portugal when news of the military coup […]