Film Review: What Can’t Be Seen

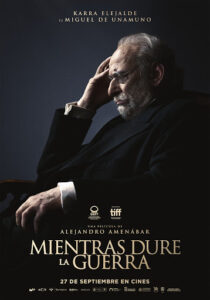

Mientras dure la guerra / While at War, dir. Alejandro Amenábar, 2019.

La trinchera infinita / The Endless Trench, dir. Jon Garaño, Aitor Arregi, and Jose Mari Goenaga, 2019.

Spain’s memory boom of the last few decades has produced a flood of new films on the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath that invite the public to identify with the defeated Republicans. Unfortunately, many adopt a glossy, heritage-movie-like aesthetic while they simplify history into a fairy-tale plot of good guys vs. bad. The two films under review here both manage to avoid these traps. While at War, by blockbusting director Alejandro Amenábar, charts philosopher Miguel de Unamuno’s political and emotional roller-coaster ride during the final months of his life, as his initial support of Franco’s July 1936 military coup turned to a sharp condemnation. The Endless Trench, by Aitor Arregi, Jon Garaño, and Jose Mari Goenaga, tells the story of a modest town councilor in an Andalusian village who escapes persecution from the Francoists by holing up behind a false wall in his home for 33 years, from the beginning of the war in 1936 until a 1969 amnesty.

Spain’s memory boom of the last few decades has produced a flood of new films on the Spanish Civil War and its aftermath that invite the public to identify with the defeated Republicans. Unfortunately, many adopt a glossy, heritage-movie-like aesthetic while they simplify history into a fairy-tale plot of good guys vs. bad. The two films under review here both manage to avoid these traps. While at War, by blockbusting director Alejandro Amenábar, charts philosopher Miguel de Unamuno’s political and emotional roller-coaster ride during the final months of his life, as his initial support of Franco’s July 1936 military coup turned to a sharp condemnation. The Endless Trench, by Aitor Arregi, Jon Garaño, and Jose Mari Goenaga, tells the story of a modest town councilor in an Andalusian village who escapes persecution from the Francoists by holing up behind a false wall in his home for 33 years, from the beginning of the war in 1936 until a 1969 amnesty.

Both movies have won many awards in Spain and both boast wonderful cinematography and impeccable period sets and costumes. Yet they are anything but glossy. Both films make a smart use of darkness to show what cannot be seen. In The Endless Trench, it cloaks the restricted vision of the holed-up protagonist. In While at War, which attempts the difficult task of representing ideas through a visual medium, darkness has engulfed Unamuno’s anxiety-ridden home and the institutions that cramp freedom of expression.

For Amenábar, this isn’t the first time he’s risked making a film with a philosopher protagonist. His English-language Agora (2009) focused on the fourth-century Alexandrian woman philosopher Hypatia. Unamuno—known for his austerity—is an even less sexy subject for a movie. (In Agora, Amenábar could at least cast Rachel Weisz as Hypatia.) Still, Karra Elejalde’s Unamuno is brilliantly convincing. Much of the film consists of Unamuno’s arguments with Republican friends as he stubbornly clings to his belief that Franco’s coup will restore order. (Having raised the Republican flag on Salamanca’s City Hall as a Republican deputy in April 1931, in the years following he had become progressively alienated by what he saw as the Republic’s exclusionary politics.) The film’s dispassionate representation of Unamuno makes us aware of his unvoiced feelings, but its greatest strength are perhaps the women: Unamuno’s daughter María, who argues back at him, as well as the wives of his arrested friends, who are largely responsible for making him recognize that he was wrong.

Unamuno famously promoted contradiction as a way of life, and in the DVD extras Amenábar explains that he wanted to make the point that a debate between opposing positions is healthy in and of itself. Still, the film fails to properly explain the background to Unamuno’s initial support for Franco’s coup. It does a better job showing his disillusionment with the crassness of the military leaders and his painful realization, as more and more of his friends are shot or arrested, that he got things wrong. The plot predictably culminates on October 12, 1936, when Unamuno, as Rector of the University of Salamanca, takes advantage of his Día de la Raza speech—a ceremony attended by some of the coup’s military leaders—to denounce Nationalist violence in no uncertain terms. In this scene the film omits a central detail, probably because it would have been complicated to explain. Every year, Unamuno would use the occasion to honor the Philippine intellectual José Rizal, who was shot by the Spanish colonial authorities in 1896. According to Unamuno’s biographers Colette and Jean-Claude Rabaté, it was this tribute that provoked the Nationalist general Millán Astray, as a teenage hero of the colonial war in the Philippines, to jump up and interrupt Unamuno with the infamous cry “Long live death! Death to intellectuals!”

Unlike Amenábar’s film, The Endless Trench is not a drama of ideas, although it does depict the invisible and mostly unvoiced thought processes of its protagonist, Higinio, the sole surviving councilor in an Andalusian village where all the other Republican councilors are shot by the Nationalists. The film’s length, at 2 hours 21 minutes, makes the point that 33 years in hiding is a very long time indeed. And this film, too, is a tribute to the strength of women: Higinio’s wife Rosa keeps him going, fending off harassment and earning a living as a seamstress. While the couple’s marital tensions help ward off sentimentalism, the movie also avoids high drama. When Higinio finally emerges into daylight, after initially mistrusting the news about the 1969 amnesty, there is no heroic welcome. In fact, no one notices him; he’s simply a man forgotten. The same restraint is evident in the film’s soundtrack, which relies less on music than on a sophisticated array of noises, which are all Higinio has to figure out what’s going on beyond his hiding place. Several sequences are shot in near or complete darkness, while intense use of point-of-view shots alternate with extreme close-ups of Higinio’s eyes peeping through the cracks in the entrance to his hideout.

Unlike Amenábar’s film, The Endless Trench is not a drama of ideas, although it does depict the invisible and mostly unvoiced thought processes of its protagonist, Higinio, the sole surviving councilor in an Andalusian village where all the other Republican councilors are shot by the Nationalists. The film’s length, at 2 hours 21 minutes, makes the point that 33 years in hiding is a very long time indeed. And this film, too, is a tribute to the strength of women: Higinio’s wife Rosa keeps him going, fending off harassment and earning a living as a seamstress. While the couple’s marital tensions help ward off sentimentalism, the movie also avoids high drama. When Higinio finally emerges into daylight, after initially mistrusting the news about the 1969 amnesty, there is no heroic welcome. In fact, no one notices him; he’s simply a man forgotten. The same restraint is evident in the film’s soundtrack, which relies less on music than on a sophisticated array of noises, which are all Higinio has to figure out what’s going on beyond his hiding place. Several sequences are shot in near or complete darkness, while intense use of point-of-view shots alternate with extreme close-ups of Higinio’s eyes peeping through the cracks in the entrance to his hideout.

The story is punctuated by a series of thought-provoking intertitles. The sequence titled “Ally,” for example, juxtaposes radio reports on Eisenhower’s 1959 visit to Franco’s Spain—betraying the Allies’ World War II fight against fascism—with the alliance Higinio establishes with the gay couple who use his house for their trysts while Rosa is away. Higinio keeps their secret in exchange for food. The point is clear: Francoism forced both the republican defeated and sexual dissidents into the closet.

The Endless Trench, now available on Netflix, has deservedly been a greater audience success. But While at War is an uncomfortable reminder that the story of the Spanish Civil War cannot be simplified into a mere two positions—Republicans versus Nationalists. There were many more in between.

Jo Labanyi is Professor Emerita at NYU. Her books include the co-authored Cultural History of Modern Literatures in Spain (Polity, 2021). She is working on a cultural history of the Spanish Civil War.