From Toulouse to Trotsky’s Assassin: The Story Behind an Iconic Photograph

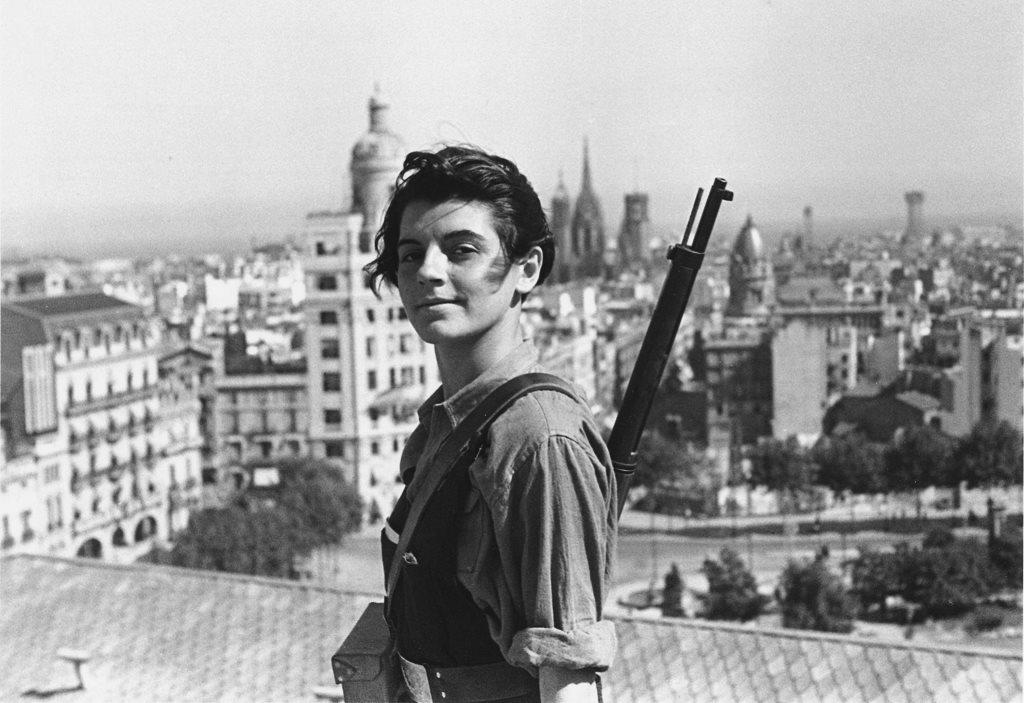

Marina Ginestà on the roof of the Hotel Colón, Barcelona, July 1936. Photo Juan Guzmán (Hans Guttman).

Marina Ginestà became world-famous late in life when a stunning photograph taken at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War surfaced in a Spanish archive. With the help of Marina’s son, the journalist Yvonne Scholten uncovers new details of Ginestà’s adventurous life.

Dozens of book covers feature the picture of this beautiful Spanish woman. It was shot in 1936 in Barcelona on the roof of the Hotel Colón, which served as the headquarters of the communist-affiliated United Socialist Party of Catalonia (PSUC). The photographer, Hans Guttmann, was a young Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany who published his work under the Spanish pseudonym Juan Guzmán. The propagandistic power of his image is immediate and irresistible: the fight against fascism, it suggests, exudes beauty, strength, and youth. The girl in the photograph was 17 years old; she’d never held a rifle before. Her name was Marina Ginestà.

She was born in Toulouse, France, in 1919, because her parents, progressive activists, had fled the Kingdom of Spain around 1910. She grew up speaking French, Catalan, and Spanish. Her parents moved back when she was 12, shortly after the proclamation of the Republic in 1931. The outbreak of the Civil War, in July 1936, found her in Barcelona.

In the many interviews she gave later in life, she maintained that she’d never joined the armed struggle and that the only time she held a rifle was during the photo session on the hotel roof. Her son Manuel, however, has his doubts. “Marina told me she shot a rifle once, by accident,” he writes in his unpublished memoirs. “In the chaos of the first days of fighting, someone had given her a Winchester, just like the ones they used in cowboy movies. When she was showing it off to a girlfriend at the Plaça de Catalunya, smack in the middle of Barcelona, she accidentally fired it. It turned out there still was a bullet in the chamber—a classic mistake.”

Other sources also shed doubt on Marina’s insistence that she did not participate in the fighting. As it turns out, Marina makes an appearance in the diary of Mikhail Koltsov, the well-known Soviet correspondent who covered the war for Pravda and who was considered one of Stalin’s confidants. In his Diary of the Spanish Civil War, which was published in Spanish long after Stalin had had his friend liquidated, Koltsov writes that Marina never went anywhere without her heavy, antiquated rifle. He would know, because for several months Marina served as Koltsov’s interpreter, translating from Spanish to French. In fact, she’d been present at the legendary meeting between the Pravda correspondent and Buenaventura Durruti, the Anarchist leader, in mid-August 1936. Since Durruti’s French turned out to be at least as good as Koltsov’s, Marina’s services were not needed, and the two men excused her. “I wouldn’t have understood their conversation anyway,” Marina later said. “I was much too young. But they appeared to like each other a lot. They smiled and seemed to agree on everything. That, I have always thought, must have been one of the reasons why Koltsov was liquidated once he got back to Moscow. Come to think of it, I’m happy I didn’t end up in there, too, as did so many Spanish Communists after the defeat of the Republic.”

Among those who did travel to Moscow was one of Marina’s old flames, Ramón Mercader, who in 1940 would assassinate Leon Trotsky in Mexico. Here, in this photograph from 1935, is Mercader standing next to Marina.

Marina with friends in 1935. Ramón Mercader is the second from the left. Courtesy of Manuel Periáñez.

It was in Moscow where Mercader was trained as a secret agent, and it was from there that he was sent to Mexico to kill Trotsky. Manuel, Marina’s son, didn’t find out about his mother’s relationship with Ramón until much later. “In September 1960 I was spending a weekend with her,” he writes in his memoirs. “She came toward me, suddenly very pale, with an issue of Paris Match in her hand. She sat down next to me and pointed to a photograph in the magazine. A couple of weeks earlier, the caption said, Trotsky’s assassin had been released after twenty years in a Mexican prison. Not only did she know the killer, she told me, but he’d been her boyfriend back in Barcelona. They had met through Marina’s older brother, Albert, and his group of friends from the Socialist Youth. Ramón, she recalled, had been the playboy of the group, a kind of Communist Don Juan, notorious for his many conquests.” Marina was one of them. “Around 1935, she said, there’d even been a mention of marriage.”

That idea, however, met with the resistance of Ramón’s mother, Caridad Mercader, who herself was in a relationship with a Russian secret agent stationed in Spain. It was Caridad who convinced her son to go to Moscow; she was also involved in planning the attack on Trotsky. Marina knew nothing of this. But Manuel figures that his mother must have been pretty besotted with Ramón. Much later, when she was 85, she and Manuel went to see The Assassination of Trotsky, the 1972 film by Joseph Losey. “I told Marina I thought Losey had made a mistake by casting a handsome actor like Alain Delon in the role of the assassin,” Manuel recalls. “To my astonishment, my mother blushed and said, icily, ‘Ramón Mercader was much better looking than that tacky Alain Delon.’”

In an interview, Marina said she loved the film, which reminded her of the ambiance in the youth movement of the PSUC, the Catalan party that united Socialists and Communists. “Young folks today can’t imagine what that was like,” she said. “People have the impression that we cared about nothing but politics. That was partly true, but the truth was that we lived in something of a double culture. On the one hand, we were fascinated by the Soviet Union, which after all had had a real revolution. We believed in the possibilities of a new society, a new man, a new relationship between the rich and poor, more social justice. We were against the power of the church, which in Spain was extremely conservative and powerful, and against the big landowners who’d kept a large part of Spain stuck in the Middle Ages. But on the other hand, we were young and lived in Barcelona, then a relatively modern city. We were obsessed with Hollywood and the new world of cinema. We loved Greta Garbo and Jean Harlow. Personally, I was completely smitten with Gary Cooper. We saw all the westerns that came through. Those movie stars were heroes of ours as much as Lenin and Stalin were. So you could say we lived in two illusion-filled worlds: movies and politics.”

Marina spent the bulk of the war years in Valencia. After the fall of Barcelona in 1939, she fled to Alicante, where it was rumored that Russian ships were headed to rescue refugees. Instead, the thousands of people gathered in the Alicante harbor saw Mussolini’s Italian troops take over the city while singing the fascist theme song Giovinezza. Together with a friend, Marina managed to escape and make it to the Pyrenees. Her friend died during the crossing; Marina herself fell and broke an arm, but was able to enter France, where it took her several months to locate her parents and brother.

With Europe on the edge of war, the Ginestà family decided to try its luck in Latin America, where Mexico, Cuba, and the Dominican Republic were rumored to take in Spanish refugees. When their initial attempt to reach Mexico failed, Marina and her family ended up in the Dominican Republic, whose right-wing dictator Trujillo hoped that the Spanish refugees would help “whiten” the island’s population. On the boat, the S.S. De La Salle, Marina met Manuel Periáñez, a fellow refugee who also fought in the war. In December 1940 they had a son, whom they named Manuel, after the father.

By 1944 Marina and her family moved to Venezuela, where Marina found a job at the Belgian embassy, fell in love with a diplomat, and remarried. In the following decades, Marina moved in diplomatic circles without uttering a word about her rifle-toting revolutionary past. In 1953, Marina’s husband was stationed in The Hague. By then, Marina had developed a strong dislike of the diplomatic world. (Franco’s Spain boasted about its diplomatic representation in The Hague; the Netherlands was among the first foreign nations to recognize the regime.)

Marina died in 2014, three weeks before her 95th birthday. Later that year, her son Manuel re-issued two books she had published in 1976, Les antipodes and D’autres viendront. In July 2016, on the 80th anniversary of the outbreak of the war, Marina’s 17-year-old face could be seen across Barcelona on posters and banners announcing a series of commemorative events organized by the city government of Mayor Ada Colau.

Guzmán’s photo, Manuel said, was only rediscovered in 1995, in the archives of Spain’s official news agency EFE. Its worldwide publication set off a search for the identity of the beautiful girl it portrayed. Manuel, who had recognized Marina right away, got in touch with Xulio Bilbao at EFE and told his mother to give him a call. “Marina told me that Xulio almost fell off his chair when he realized he was talking to the girl in the picture. It gave her a good laugh.”

Yvonne Scholten is a Dutch writer and freelance journalist who has worked as a foreign correspondent in Italy and other countries. She has written biographies of Fanny Schoonheyt and Bart van der Schelling, who both fought in the Spanish Civil War, and has coordinated the online biographical dictionary of Dutch volunteers in Spain at www.spanjestrijders.nl. English version by Sebastiaan Faber.

Pido em nombre de todos los: Comunistas, Socialistas, ombres e mujeres bueno(as)de todos los honestos, que non dejem morir el recuerdo de la Guerra Civil Española, fue um motivo de mucho orgullo de nosotros. Tuvemos el non menos grande em la lucha Civil, Apolonio de Carvalho, el hombre de tres patrias( luchou na guerra Civil Española, contra o nazismo na French, contra a ditadura do Brazil de 1964-85.

This investigation I compare to studying the private life of Helen of Troy