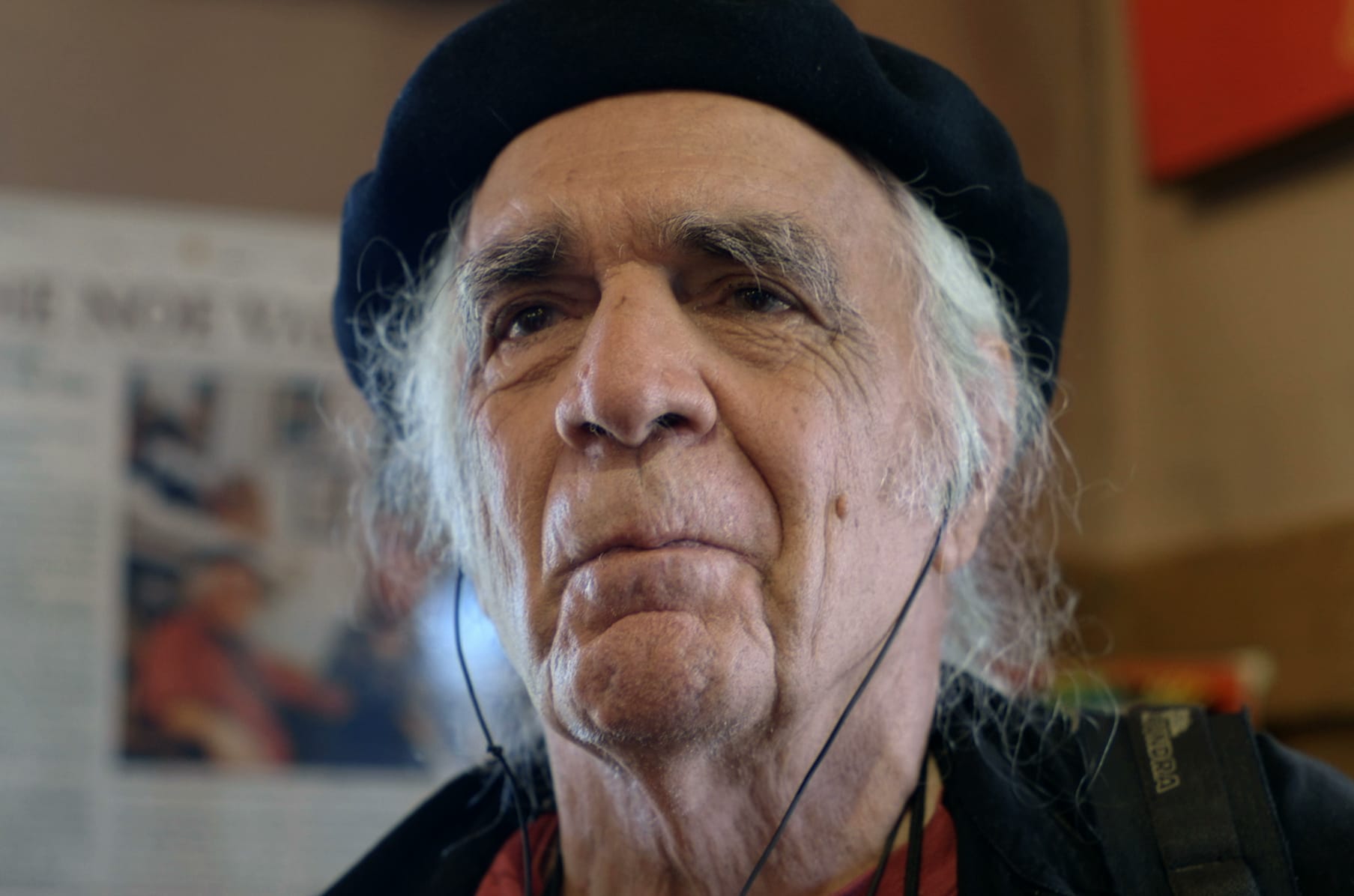

Ramon Sender Barayón: A Pioneer in Music & Memory: An interview with Filmmaker Luis Olano

Ramon Sender Barayón is a pioneer of US counterculture and the son of Amparo Barayón, who was killed by fascists in the Spanish Civil War, and the novelist Ramón J. Sender. A new documentary by Luis Olano sheds light on his remarkable life.

Ramon Sender Barayón, born in Madrid in 1934, is a pioneer of American counterculture and a fixture of the San Francisco art and music scene. A composer, visual artist, and writer, he was the co-founder, in 1962, of the San Francisco Tape Music Center, which later became the Mills Center for Contemporary Music. Together with Don Buchla, Sender designed one of the world’s first music synthesizers. He is also the son of Ramón J. Sender, a prominent Spanish novelist who fought in the Civil War and spent almost forty years in exile, and Amparo Barayón, a pioneering feminist who was assassinated by the Nationalists in her native Zamora in October 1936. Ramon Sender’s book Death in Zamora (1989) is a memoir of a son’s investigation of his mother’s politically motivated murder.

This fall, NYU’s King Juan Carlos I of Spain Center screened Sender Barayón: Viaje hacia la luz (Sender Barayon: Trip toward the Light), a new documentary by Luis Olano. A descendant of Spanish Civil War exiles, Olano was born in 1986 in St. Petersburg, Russia. He’s lived in Spain since 1991.

How did you first run across Ramon Sender?

It was during a trip to California in 2014, at the suggestion of the journalist Germán Sánchez. Sánchez, who is my second father and cowrote the documentary with me, had produced a radio story about Ramón J. Sender, the novelist. He suggested I try to locate his son. It didn’t take me long to find him through his website. It was love at first sight. Connecting with him was easy: he’s got an amazingly broad frame of reference, from the past and the present, he follows the news, and remains socially very active, also online. I remember he told us how interested he was in in the appearance of Podemos, which then had only just been founded. Being myself a grandson of a Republican exile to the Soviet Union, it was very special for me to connect with Ramon. Later, Emilio Silva, of the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory in Spain, put me in touch with Pablo Sánchez León, a historian and editor who was then about to re-issue the Spanish translation of Ramon’s memoir about his mother, A Death in Zamora. The first video interview I did with Ramon in 2014 convinced us that we had to bring the story of his life back to Spain, and to recover the memory of twentieth-century counterculture from his perspective. In November 2016 I had the opportunity to return to San Francisco, with a grant from the Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses, to tape the interview on which the documentary is based. Curiously, this was right around the time of the Trump election.

Can we think of Ramon Sender Jr. as belonging to Spanish Civil War exile? And if so, to what extent is his experience compatible with historical memory of the war and exile in Spain today?

In many ways, Ramon’s experiences are unique. Of course, he was also a victim of Francoism: his mother was killed by local fascists, and his father exiled from dictatorial Spain. But the umbilical cord tying him to Spanish culture was severed forever when he arrived to the United States as a young child and stopped using his native language. It’s important to note that Ramon was not raised by his father. In fact, he was sheltered from any information about his biological mother and the causes of her death. Once his father had rescued him from the orphanage in Zamora where he and his sister had ended up after his mother’s death, they were adopted by a wealthy U.S. family. In this way, his father gave them the opportunity to live a full life completely opposite to the obscurantism that enveloped Spain for at least forty years.

It wasn’t until after the death of his father, in 1982, that Ramon decided to return to Spain to investigate the circumstances of his mother’s death and try to resolve the trauma caused by her absence, the silence surrounding it, and his own conflicted identity. In many ways, his book Death in Zamora was groundbreaking: it recovered the memory of the female victims of the brutal Francoist repression in the rearguard. At that time, the topic was completely taboo and relegated entirely to the private sphere of the victims and their families—if they even dared to address it. So what Ramon did was not only to recover the memory of his parents’ generation, which fought for democratic liberties in 1930s Spain, but he also became a precursor, coming from exile, of the social and political culture of the younger generation of anti-Francoists who came of age toward the end of the dictatorship and the beginning of the Transition.

How has your documentary been received in Spain?

Because we have produced it ourselves and have no distributor, it’s been hard to find venues. Yet we’ve been able to do thirty public screenings in cultural centers, arthouses, and universities, thanks in large part to the support of the memory movement. The documentary has also been selected for festivals in Madrid, Lugo, Valencia, and Greece. The public’s response has been very positive. Ramon’s testimony, along with Death in Zamora, speaks to a part of Spain’s historical narrative that has been purposely hidden from sight, silenced by the institutions of democratic Spain. The same happened with the exhumations of mass graves that the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory started to undertake twenty years ago. As the bones emerged, as a visible proof of Francoist repression, the victims’ families showed up at the excavation sites and, breaking with a deeply rooted routine of forgetting and silence, finally began to speak. In the same way, when we premiered the documentary in Zamora, the entire city felt this was something that concerned them. The film helped to return to the city’s memory a story that had been buried, but that everyone knew: the cruel and unjust murder of the innocent Amparo Barayón.

Still, we ran into roadblocks. In the early summer of 2018, as we were finishing up editing the documentary, the new edition of Death in Zamora was presented at the Zamora Book Fair. The newspaper in charge of covering the Fair, La Opinión de Zamora, decided not to mention the book presentation, despite its obvious significance for the cultural and political history of the city, and despite the fact that it was one of the Fair’s official events. This was clearly not an oversight. Fortunately, the attempt at censorship unleashed a campaign on social media that pushed the paper to retract, albeit timidly, and to publish the briefest of notes about the presentation the next day.

Now, by the time we premiered the documentary in Zamora, the situation had changed completely. By then, the book’s first edition had almost sold out; it had done particularly well in Zamora bookstores. The morning of the premiere, the same paper that had tried to silence the book presentation, La Opinión de Zamora, announced the screening on the front page, with a full-page article on the inside. The city embraced the opportunity to meet the prodigal son from exile and to remember, vindicate, and pay tribute to a woman who’d been a pioneer of emancipation and democracy, a true Zamora “martyr.” This is particularly stunning if we consider that the Holy Week processions in Zamora are closely linked to Franco’s ideology of national-Catholicism, and include fraternities of army veterans.

The premiere drew more people than fit in the theater. Many carried their copy of Death in Zamora, some even of the first Spanish edition, which came out in 1990. An added controversy came up when some local officials of the Socialist Party took advantage of the opportunity to have an unannounced press conference in which they took a conservative regional senator to task for criticizing government subsidies for historical memory initiatives.

But the strangest moment happened two hours before the premiere. Just outside the theater, I was approached by one of the grandsons of the governor who had signed Amparo Barayón’s execution order. He’d recognized me from the picture in the newspaper. When Ramon had returned to the city in the 1980s, he’d interviewed the descendants of the perpetrators, but they hadn’t expressed any regret, while La Opinión de Zamora slandered his mother. Now, however, the governor’s grandson told me he was sorry he couldn’t attend the screening but that he wanted to thank me for telling the truth about Amparo Barayón, one of the many innocent victims of the terror in which his ancestors were complicit. Clearly, something has shifted in the past thirty years.

Do you think that your portrait of Ramon Sender Barayón changes the image of his father, the world-famous novelist?

Our portrait tries to create a dialogue between those two biographies, which are really each other’s polar opposites in cultural, ideological, spiritual, and aesthetic terms. Ramón J. Sender, the novelist, was a man tormented by the trauma of war as well as the murder of his life partner and his brother. Not only does this move him to abandon his children, but also to practically lock himself up into literature for the rest of his life. His son, on the other hand, closes his testimony in our film thanking his father for making it possible for him to live a full life in the United States. Ramon understands full well that, following his mother’s execution, he and his sister were about to be handed over to a Francoist family.

Ramon also seems to acknowledge that his father was simply incapable of confronting his own trauma and guilt. In some way, Ramon’s own quest for identity and community, but also the search for his biological mother and his Spanish roots, became a self-curing process: a resolution that he, as son, was able to accomplish even if his father was not.

Ramon has spent his entire adult life investigating tools for physical and spiritual well-being. The generosity with which he shares his experience suggests that he’s trying to share a tool to confront the psychological wounds brought on by a dearth of memory, forced absences, and a lack of truth, justice, and reparation.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College.

That you so much, Sebastian, for your interview with Luís, and Luís again my deepest thanks for all your time and effort towards making the documentary a reality. It is true that I have spent much time searching, like Don Quixote’s son, for what I call ‘a universal panaçea,’ something that anyone can do to feel good, even if they are laid up in hospital with all four limbs in traction. Therefore I was delighted to run across two books by a Julie Henderson who focuses on the body-mind connection. All of her exercises fit my ‘universal panaçea’ guidelines, so I submit an e-copy of her book here, as I am doing to all my friends. If you find it helpful, consider a love offering to Julie, now in her eighties (and somewhat hard to reach I have found). I have been using PayPal to mail her whatever sums arrive and you can use it for me via my email address, even if you do not have a PayPal account (I am told). Best Wishes – I believe we will emerge from the pandemic permanently changed for the better, perhaps a type of ‘backdoor socialism’ that I like to call ‘communal-itarianism.’ will have to research others’ use of the word. before promoting it further. Best Wishes, All, – Ramón

https://www.dropbox.com/s/oosxxvrag4jbow1/Embodying%20Well-Being%20e-final-2.pdf?dl=0

I am taking a history of Spain class entitled America and World Fascism from ALBA and last week they talked about Ramon Sender Barayon, his interview, the movie and his book, Death in Zamora. Brigadista Del Berg gave me as a gift Ramon’s signed book in 2011 when I interviewed him at his home in Columbia about his involvement in the Spanish Civil War. I read the book as soon as Del gave it to me in 2011 and this week I read it again. What a precious piece of history! Thank you very much for telling the world about this part of history and the account of your own personal life Ramon.

I met Ramon Sender Barayon when he was hired to wash laboratory glassware at NYU, where I was a research associate. He was a student at Columbia University at the time and only now have recognized that he is the author of “A Death in Zamora,” which I have recently read. I would like to write a few words to him to express my admiration for his work. Can you supply me with his current email address?

Hi Michael:

Always a pleasure to read from you.

My email: ramon.sender@gmail.com

website: http://www.raysender.com

My author’s page on Amazon:

https://www.amazon.com/s?