The Inimitable by James Ruskin

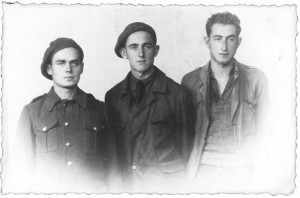

Wisconsin volunteers (standing) Fred Palmer, John Cookson, and Clarence Kailin. Photograph Clarence Kailin, ALBA/VALB.

The Volunteer for Liberty, V2, no. 33, October 6, 1938

There is not a man of us who did not like and appreciate Teniente Johnny Cookson Adjutant of the Transmission Company of the 15th Brigade for he combined the rare qualities of a man of science, a good organizer, and a sincere simple and lovable person.

Nineteen months ago he was plunged into the early chaos of the original “Genie” Company. The first question he asked me on his arrival was about the possibility of using radio in the Brigade and his enthusiasm and energy were unabated to the very last day. He struggled hard to raise the technical level of our Company, to create order out of chaos.

The second time I met him at Brunete, he was maintaining the communications of the Washington Battalion. He was tired but untiring despite the many miles of wire burned by enemy incendiary bombs. After a stay on the southern front he was back with us again at Batea and at the most critical times he kept both his head and his high spirits. Left at Batea with the Lincolns he managed to pick up most of the wire and practically all the telephones and with six other comrades he made his way back to our forces through the enemy lines. On one occasion they met a fascist column marching along the road; it was too late to escape, so they simply marched with them. When challenged they used the magical password “Transmissiones” – and it worked. Two days later Cookson arrived with his little group, practically unshod, his clothes torn, dirty, unshaven, hungry and tired – but still carrying a telephone and a coil of wire!

He took interest in all the phases of our work, and there were few men who wore out as many pairs of alpargatus as he did on the hills of this Spanish earth, finding the best and shortest way to lay his lines. In his inimitable Spanish and with the help of a black board, he could instruct our Spanish comrades in the science of transmission.

It was almost impossible to refrain from pulling Johnny’s leg about his Spanish, but he never got upset about the kidding. On the contrary he turned his unconscious humor into supposedly conscious humor. Such little tricks of his made his lectures and his conversation not only instructive and interesting but also extremely amusing. He thought much more rapidly than he could speak and whenever he wanted to explain something in a hurry he would skip words, interchange syllables and utilize peculiar expressions we christened “Cooksonian.”

On one occasion he told me that three linesmen were “adamant” to go on the line. Naturally, I said “Well, let them go.” “No.” he said, “they are rather adamant.” I enquired who was stopping them to which he replied, “Nobody.” Then it dawned on me that he might mean reluctant, which I suggested to him rather timidly. “Yes,” he said, “of course they are reluctant; can’t you understand.”

For Johnny was a great lad for arguing. He would argue about scientific, political or ethical subjects; about wireless, telephony or any subject under the sun. Displaying a deep and wide knowledge and a subtle sense of humor.

In the Ebro operation he worked day and night and it was impossible to make him rest during action. Only when we were sent into a reserve position would he fall asleep under a tree, completely oblivious to the outside world. Even the arrival of the grub would not wake him.

He was altogether unassuming and never seemed to bother about his personal comfort. To see Johnny with torn alpargatus without blanket no mess kit was the usual thing. And he never grumbled.

Nor did he lose his scientific interest in the world about him. In the midst of a heavy shelling you could hear him count the number of seconds that elapsed between the flash and the detonation of a shell, in order to calculate the distance of the explosion. In his spare time he wrote letters to his family, friends and associates urging them to work for Spain and against fascism. At rest he permitted himself the luxury of studying the quantum theory.

Johnny was a promising young scientist and had done some valuable original work in crystallography. He had a secure job at home, he had work that he enjoyed. Yet he considered it his duty to come here to fight. He gave all his enthusiasm his energy, his knowledge and finally his life to that cause.

We respect and admire Johnny for his knowledge, his splendid work; and we love him for his great, kind heart which found expression in so many inimitable ways. Another Antifascist hero is dead; but he will live in our hearts until we also die.

James Ruskin, Chief of Transmissions, XVth Brigade