New Archive Traces New Zealand Volunteer in the IBs

An archival donation reveals new details about Griff Maclaurin, a charismatic New Zealander who left Cambridge, England, to serve as a volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, where he fought alongside the poet John Cornford and died in the battle for Madrid. “When he was wounded he propped himself up against a tree and continued to fire his gun … [H]e was found standing there days later so riddled with machine gun bullets that his body fell apart when they tried to pick it up.”

A public archive in New Zealand has recently received the voluminous correspondence between Joan Conway, sister of New Zealand volunteer Griffith Maclaurin, and her US-based friend Gwen Davies Koblenz. Their letters paint a fascinating portrait.

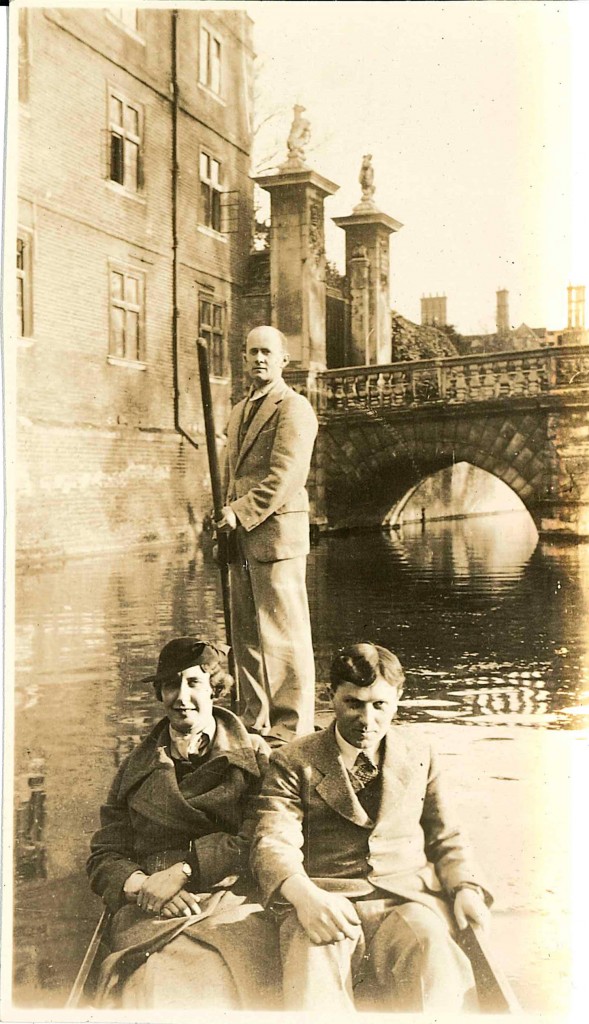

Griff Maclaurin had been a brilliant student of mathematics at Auckland University College in 1928-1931 and took up a postgraduate scholarship at St John’s College, Cambridge in England. Although initially of conservative views, he became deeply immersed in the radical politics of the 1930s and joined the British Communist party. In one of her letters, Joan says her brother’s radicalization stemmed from encounters with Nazism during a three-month tour of Germany in 1933. The following year he opened a leftwing bookshop in All Saints Passage, near the university.

Maclaurin’s Bookshop was Cambridge’s first progressive bookshop and became extremely popular. One customer, the historian Eric Hobsbawm, considered it “the center of left literature in Cambridge.” The orange-covered Left Book Club titles published by Victor Gollancz were a large part of its stock in trade. Gollancz later wrote that Griff’s “letters to us with their idealism and enthusiasm were a constant source of inspiration.”

Among Griff’s circle of friends at Cambridge was Gwen Davies, who grew up in north Wales and whose father was a professor of Celtic Studies. She took a degree in botany at Oxford University in 1931, and joined the staff of the Low Temperature Research Station at Cambridge. There she became active in leftwing politics, meeting the poet John Cornford and the philosopher and publisher Maurice Cornforth, among others.

Soon after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, Griff was recruited to the International Brigades by Harry Pollitt, head of the British Communist party, because of Maclauren’s experience with a WWI-era Lewis machine-gun while serving in the officers’ corps at Auckland Grammar School. He arrived in Spain in October 1936 and served with a small machine-gun unit of Britons attached to the Commune de Paris Battalion. One of his British comrades, David MacKenzie, said Griff had “a splendid capacity for distracting our minds from the more unpleasant realities of life; from the small, kind ever-laughing face it would have been difficult to identify him as a military hero; but such he proved to be.”

“From the small, kind ever-laughing face it would have been difficult to identify him as a military hero; but such he proved to be.”

The machine-gun unit was stationed in the University City, on the western side of the capital adjoining a wooded area, the Casa de Campo. On the evening of November 7, 1936 Griff and three other machine-gunners, including fellow New Zealander Steve Yates, left the comparative safety of the university buildings to establish a defensive position within the wood.

Mackenzie later wrote:

The fascists were cleared out of it in the evening without much difficulty. Maclaurin with Steve Yates took their Lewis gun along the right hand side of the wood. They had no-one to carry their ammunition, and Maclaurin carried it all and his rifle as well. He was wounded almost immediately, but it was at the far end of the wood that his body was found, dead beneath a tree with the Moorish sniper whom he had shot down beside him. Yates continued alone with the machine gun and the ammunition. He was the first to reach the gate at the end of the wood, giving covering fire as our men passed through it. When he was wounded he propped himself up against a tree and continued to fire his gun, firing from the hip at the Moors round the house, and he was found standing there days later so riddled with machine gun bullets that his body fell apart when they tried to pick it up.

Another member of this unit was the young English poet John Cornford. After this effective but extremely costly defensive action he wrote to his fiancée, saying that Maclaurin had been “continuously cheerful, however uncomfortable, and here that matters a hell of a lot… if you meet any of his pals, tell them he did well here and died bloody well.”

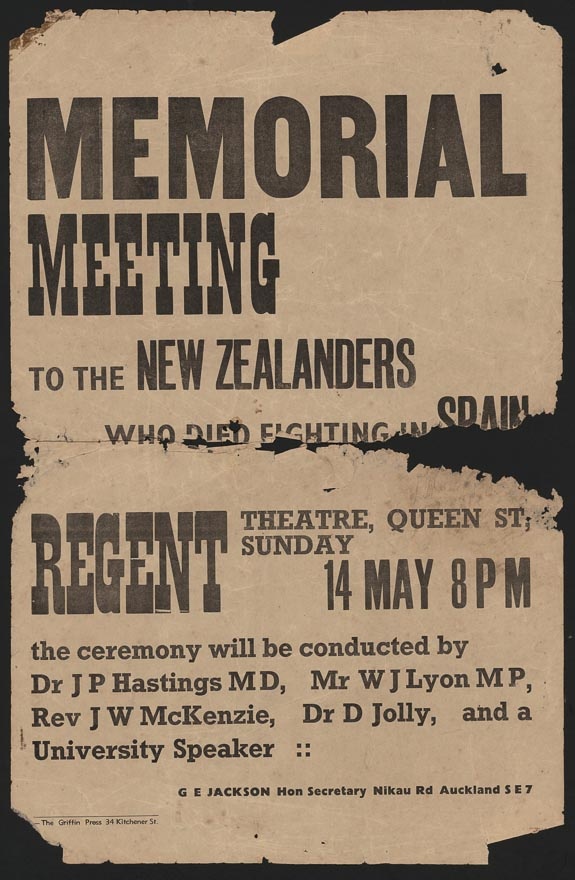

Poster advertising a memorial meeting to the New Zealanders who died fighting in Spanish Civil War (Auckland, May 1939).

Maclaurin’s family was not aware that he had traveled to Spain, and did not receive news of his death until a month later. Although both parents were from politically conservative backgrounds, they were deeply proud of their son and became active fundraisers for the Spanish Medical Aid Committee, the main New Zealand organization providing support for the Republican cause.

During the war, Gwen Davies also organized shipments of food, clothing and medical supplies for the relief of Spanish civilians and helped to resettle a group of Basque children in Cambridge. She later met Sidney Koblenz, a US Airforce sergeant stationed near Cambridge, through their mutual interest in Maclaurin’s Bookshop, which remained in business after its founder’s death in Spain. They married in 1947 and spent the rest of their lives in the US, where Gwen worked as a medical technician in Albany, NY. She and Joan Conway evidently maintained a lifelong interest in the Spanish Civil War and in other leftwing and progressive issues.

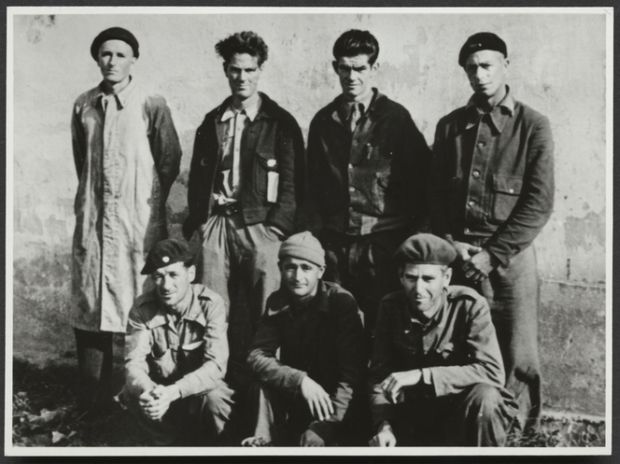

Waiting to return home from Spain in October 1938 are New Zealanders Bert Bryan (front centre) and William “Murn” MacDonald (back, third

from left) with Australian International Brigaders. Alexander Turnbull Library

Around New Zealand, memorials to local veterans of the Spanish Civil War have begun to appear in recent years. As reported in The Volunteer June 2018, a plaque was recently unveiled to the battlefield surgeon Doug Jolly in his hometown of Cromwell. A number of New Zealanders, including Griff Maclaurin’s relative Max Maclaurin, share the opinion of Griff’s parents that this short-lived yet spirited and inspiring figure also deserves to be remembered in the city where he grew up and studied. They are planning to install a memorial plaque to him, perhaps at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, the country’s largest regional museum.

Maclaurin provided his own best epitaph as he left for Spain in September 1936. Farewelling his fellow New Zealander Paddy Costello from a departing train at London’s Victoria Station, he prophesized that he would have “a short life, Paddy, but a merry one.”

Mark Derby is currently writing a biography of Doug Jolly, a New Zealand surgeon who served with distinction in the Spanish Civil War.