Violence against Women in the Spanish Civil War

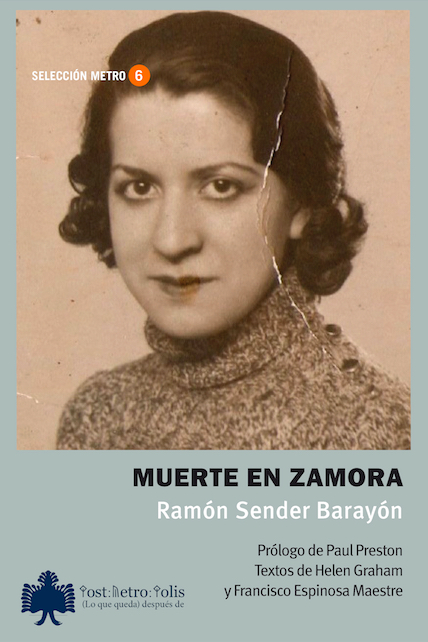

The following text is based on Paul Preston’s introduction to the Spanish re-edition of Ramón Sender-Barayón’s A Death in Zamora (Postmetrópolis, 2018), in which the son of Ramón J. Sender and Amparo Barayón investigates the circumstances of his mother’s death three months after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War.

One of the least well known aspects of the repression against civilians carried out by the partisans of Franco’s military coup against the Spanish Republic is the scale of their deliberate and systematic persecution of women. Throughout the rebel zone, many women were murdered and thousands of the wives, sisters and mothers of executed leftists were subjected to rape and other sexual abuses, the humiliation of head shaving and public soiling after the forced ingestion of castor oil. Murder, torture, and rape were generalized punishments for the gender liberation embraced by most liberal and left-wing women during the Republican period. Moreover, for Republican women, there were also the terrible economic and psychological problems of having their husbands, fathers, brothers and sons murdered or forced to flee into exile, which often saw the wives themselves arrested in efforts to get them to reveal the whereabouts of their men.

They and the many women who had been politically active faced appalling conditions in overcrowded, unhygienic prisons in addition to being subjected to sexual abuse. Those who came out of prison alive suffered deep life-long physical and psychological problems. After the war, the cruelty visited upon women was justified by a Catholic rhetoric of “redemption.” As well as confiscation of goods and imprisonment as retribution for the behavior of a son or husband, the widows and the wives of prisoners were raped. Many were forced to live in total poverty and often, out of desperation, to sell themselves on the streets. The consequent increase in prostitution both benefited Francoist men who thereby slaked their lust cheaply and had the satisfaction of being reassured that “red” women were whores, a fount of dirt and corruption.

For a variety of reasons, more is known about the sexual violence carried out in the areas of Andalucía and Extremadura than the experiences of the relative minority of Republican women in northern Spain. The extent to which the abuse of women was official policy can be deduced from the speeches of General Queipo de Llano who was effectively the viceroy of southern Spain. His daily broadcasts were larded with sexual references, describing scenes of rape with a coarse relish that encouraged his militias to repeat such scenes. In one notorious speech, Queipo de Llano declared: “Our brave Legionaries and Regulares have shown the red cowards what it means to be a man. And incidentally the wives of the reds too. These Communist and Anarchist women, after all, have made themselves fair game by their doctrine of free love. And now they have at least made the acquaintance of real men, and not milksops of militiamen. Kicking their legs about and squealing won’t save them.”

Throughout the rebel zone, many women were murdered and thousands of the wives, sisters and mothers of executed leftists were subjected to rape and other sexual abuses.

Comparable atrocities were committed in the north albeit on a lesser scale and without the kind of publicity generated by Queipo de Llano. For instance, the conquest of Catalonia by Franco’s forces throughout the second half of 1938 witnessed horrific scenes of sexual violence. Similar abuse occurred in the deeply Catholic areas of Castille and León. One of the most extreme examples of the impact on innocent women of the repression was what happened in the town of Zamora to Amparo Barayón, the wife of Ramón J. Sender, world-famous novelist and anarchist sympathiser. Sender and his wife and their two children were on a holiday in San Rafael in Segovia at the beginning of the war. He decided to return to Madrid and told Amparo to take the children to her native city of Zamora where he was sure they would be safe. In fact, on August 28, despite being a Catholic, she was imprisoned along with her seven month-old daughter, Andrea, after protesting to the military governor that her brother Antonio had been murdered earlier the same day. This 32-year-old mother, who had committed no crime and was barely active in politics, was mistreated and eventually executed on October 11, 1936. Her crime was to be a modern, independent woman, loathed because she had escaped the stultifying bigotry of Zamora and had children with a man to whom she was married only in a civil ceremony.

Amparo was not alone in her suffering. Kept in below-zero temperatures, without bedding, other mothers saw their babies die because, themselves deprived of food and medicines, they had no milk to breastfeed them. One of the policemen who arrested Amparo told her that “red women have no rights” and “you should have thought of this before having children.” Another prisoner, Pilar Fidalgo Carasa, had been arrested in the nearby town of Benavente because her husband, José Almoína, was secretary of the local branch of the Socialist Party. Only eight hours before her detention and transport to Zamora, she had given birth to a baby girl. In the prison, she was forced to climb a steep staircase many times each day in order to be interrogated. This provoked a life-threatening haemorrhage. In her account of her treatment published in exile, A Young Mother in Franco’s Prisons, she wrote, “Because I continued haemorrhaging, I constantly begged the warden for help. Finally she brought the prison doctor Pedro Almendral who came merely as a matter of form. Upon seeing my suffering, he commented that ‘the best cure for the wife of that scoundrel Almoína is death.’ He prescribed nothing – neither for myself or my baby.” Numerous young women in the prison were raped before being murdered.

Pilar Fidalgo’s horrifying memoir is not the only evidence of what happened to women in Zamora. The investigation into what happened to Amparo, A Death in Zamora, is a deeply moving, indeed deeply upsetting book, which has much to say to several different audiences. The central narrative relates the quest by a man brought up in the United States to discover the fate of his mother in Spain during the Civil War of the 1930s. The author, Ramón Sender- Barayón, is the son of Amparo and Ramón J. Sender. His mother was a target for the military rebels simply because of her husband’s fame as a left-wing novelist. He had told her to flee to Zamora on the assumption that she would be safe there with her Catholic family. In his book, the painful and painstaking research of Ramón Sender-Barayón finally managed to reveal the truth of how she was imprisoned, tortured, and eventually executed—her horrendous fate typical of what happened to many innocent women at the hands of the supporters of General Franco.

The painful and painstaking research of Ramón Sender-Barayón finally managed to reveal the truth of how Amparo was imprisoned, tortured, and eventually executed.

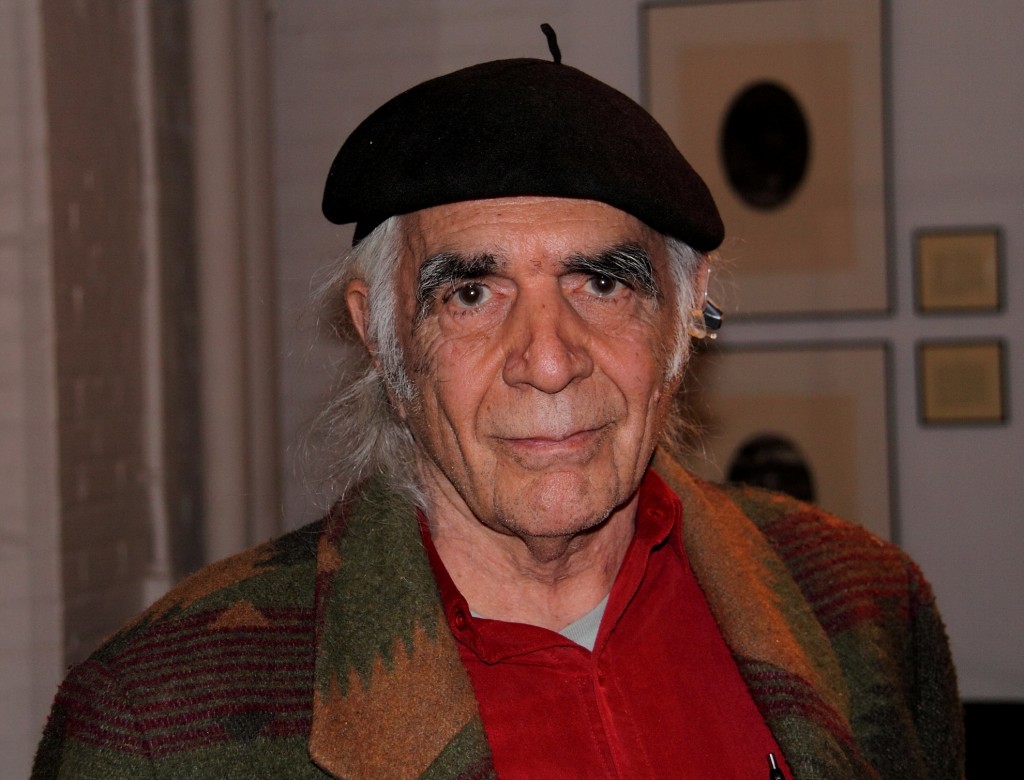

In that sense, the book is a major contribution to the history of right-wing atrocities during the Spanish War. In addition, however, the subsequent story of how Ramón J. Sender took his two children to the United States and then virtually abandoned them is also harrowing in its way and makes for a tragic psychological drama that will be of interest to many people not concerned with Spanish history. The story of Ramón Sender-Barayón’s quest also happens to be a riveting detective story. I read the first edition of this book nearly 20 years ago and immediately bought several copies to give to friends and their reaction confirmed my own. One of the people to whom I sent a copy was my great friend and mentor Herbert Southworth who worked in Washington during the Spanish Civil War for the last Republican Prime Minister, Dr Juan Negrín. Herbert was very excited when he read the book and told me that he remembered going with his friend, the great journalist Jay Allen, to meet Ramón and his sister at the docks in New York when they arrived.

A Death in Zamora is a unique contribution to the quest for the memory of what happened to innocent civilians during the Spanish Civil War. It is an important and neglected masterpiece which I recommend to every reader of The Volunteer.

Sir Paul Preston is a Professor Emeritus at the London School of Economics, where he heads up the Cañana Blanch Centre for Contemporary Spanish Studies.

[…] https://albavolunteer.org/2018/08/violence-against-women-in-the-spanish-civil-war/ […]