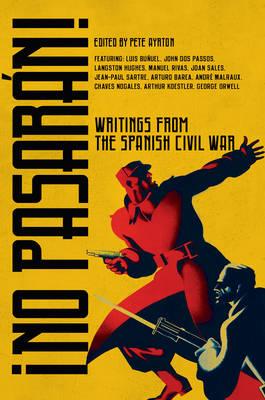

Book Review: No Pasarán: Writings from the Spanish Civil War

No Pasarán: Writings from the Spanish Civil War. Edited by Pete Ayrton. London/New York: Pegasus Books, 2016. 393pp.

No Pasarán: Writings from the Spanish Civil War. Edited by Pete Ayrton. London/New York: Pegasus Books, 2016. 393pp.

Since 1936, the cry ¡No Pasarán! (first used by the French during World War I) has come to symbolize the will of the Spanish people to stand up to enemies of freedom and democratic rule. This collection of writings assembled by Pete Ayrton reflects the multiple perspectives that Spaniards and foreigners alike held at the time and since. And while the title is somewhat misleading—some of the viewpoints expressed were written years after the civil war ended—this book offers a diverse and representative array of perspectives on Spain’s epic conflict.

Of the numerous literary collections in English published on the Spanish Civil War, few have included translations of Spanish writers, participants, and intellectuals who bore witness to events as they unfolded on both the Republican and Nationalist sides. Those which have—the excellent anthologies of Robert Payne (The Civil War in Spain, 1961) and Alun Kenwood (The Spanish Civil War: A Cultural and Historical Reader, 1993), for example—are either out of print or aimed at a specialized audience. In fact, one of Ayrton’s stated goals in publishing this anthology is to introduce to a largely Anglophone audience the voices of Spaniards who either directly experienced the war or whose lives under Franco’s rule were shaped by it.

Ayrton introduces to an Anglophone audience the voices of Spaniards who experienced the war and its aftermath.

To help those unfamiliar with the contours of the civil war’s historical landscape, Ayrton has provided a useful outline of the major themes covered by the selected authors. Chapters devoted to the war at the front and in the countryside are not just about the battlefield experience of foot soldiers on both sides of the struggle. The excerpted essay (The Moors Return to Spain) by the Republican journalist Manuel Chaves Nogales, for example, provides an unvarnished portrait of the bloody fate of Moorish militiamen who were used as shock troops by the Nationalist army. Though this vivid account is replete with racial stereotypes regarding the character of the Moors—their alleged rapacious appetite for bloodletting and abusing their vanquished opponents—it offers a window into a little-known dimension of the war. Such selections illustrate a point the author raises in his introduction: The International Brigades were not the only foreigners who fought in Spain. The reader comes away with a clear impression of how the Moors understood their role as jihadists fighting against the godless “reds”, as well as how their enemies on the left viewed them.

Other themes include writings relating to the Republicans’ assault against the Catholic Church, the impact of bombing on the civilian population, and the role of women in the war. The scope of these chapters underscores the fact that the issues raised by the civil war cannot be explained simply in terms of good and bad. In a refreshing change from previous anthologies, the author has included right-wing writers like Drieu la Rochelle, whose provocative essays show why the European right outside of Spain chose to view the Spanish conflict as a harbinger of the final showdown in Europe’s politically polarized cultural wars.

Yet for all his efforts to sketch the features of a complicated event, the author missed the opportunity to fill in some of the glaring gaps in our understanding of the civil war and the popular revolution it triggered on the Republican side. For example, there is little about the experiences of the hundreds of thousands of Spaniards who attempted to use the war as a stepping-stone for a revolutionary restructuring of Spanish society. In Ayrton’s defense, this oversight might be due to the fact that eyewitness accounts of this highly dramatic and often bewildering phase of the civil war have appeared in English (Franz Borkenau and George Orwell) or in translation in books published since 1936. Similarly, in this collection readers are given only glimpses of the “red” terror (Gironella) and attempts by the extremists to impose their revolutionary agenda (“A Proletarian Bullfight” and “Of Love and Marriage”) as the old order began to unravel in the wake of the July military rising.

While this anthology is weighted towards a Spanish perspective, another strength is that Ayrton has not ignored observations of the diverse group of foreigners who visited Spain during the war. Journalists and celebrity writers often had more privileged access to events than the average Spaniard, and their accounts offer insights not only into the larger picture behind the lines but also of the mundanities of everyday life. The African-American writer Langston Hughes’s tongue-in-cheek account of how madrileños reacted to an artillery shelling while they were watching the American film Terror in Chicago is a case in point. Rather than seek shelter from incoming shells, the audience displayed an unexpected yet quintessentially Spanish kind of wartime resiliency:

Suddenly an obús [shell] fell in the street outside. There was a tremendous detonation, but nobody moved from his seat. … Soon another fell, nearer and louder than before, shaking the whole building. The manager went out into the lobby. … Overhead he heard the whine of shells … he thought it best to stop the picture. Before he got the words out of his mouth he was greeted with such hissing and booing and calls for the show to go on that he shrugged his shoulders in resignation and signaled the operator to continue.

Among the legacies of Spain’s tragic war are the remarkable literary and cultural works that were produced during the conflict and afterward. Ayrton has provided an engaging and diverse sampling of those writings.

George Esenwein is an Associate Professor of History at the University of Florida, Gainesville. He is the author most recently of The Spanish Civil War: A Modern Tragedy (2005).