A Pig Islander among the Mac-Paps

Albacete, Spain

16 July 1937

Dear comrade

I guess you folks have heard that I got over here. There is another New Zealander in our battalion, Wm, McDonald, of Dunedin. He is the only “Pig Islander” I have seen, though it is reported there is a fellow Spiller somewhere around.[1]

As a sergeant in the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, Alex Maclure firmly aligned himself with New Zealand volunteers in the International Brigades. In the above letter, published in the Communist Party of New Zealand’s Workers’ Weekly, he refers to himself as a ‘Pig Islander’, a term then applied to New Zealanders by other nationalities. Yet Alexander Crocker Maclure had been born in Canada, and he only arrived in New Zealand in 1931, aged 19, to study at Otago University.

Maclure was raised in a middle-class family in Anglophone Montreal, and from an early age showed signs of an adventurous and independent spirit. At high school he not only excelled at mathematics and other subjects, but won awards for marksmanship.[2] After graduating, he left for Fort Churchill in subarctic northern Manitoba to work as a ship’s radio operator. For the next two years, according to his brother Ken, ‘he worked in the main among labouring men, especially of the seafaring variety… he said that no matter how black a reputation some men might have, after he got to know them he invariably found something to like and admire in them.’[3]

Maclure then enrolled at the School of Mines in New Zealand, which had a distinguished international reputation. He entered the mining course at Otago University, Dunedin, in March 1931. According to NZ historian Ali Clarke, there were only around 1100 students at Otago when Maclure arrived, and most were ‘conservative members of the middle class, preoccupied with completing their qualifications’. In that company, Maclure ‘quickly earned the reputation of being the most politically radical person on campus’.[4]

Maclure then enrolled at the School of Mines in New Zealand, which had a distinguished international reputation. He entered the mining course at Otago University, Dunedin, in March 1931. According to NZ historian Ali Clarke, there were only around 1100 students at Otago when Maclure arrived, and most were ‘conservative members of the middle class, preoccupied with completing their qualifications’. In that company, Maclure ‘quickly earned the reputation of being the most politically radical person on campus’.[4]

Critic, Otago’s student newspaper, later recalled this strange Canadian student as, ‘Maclure the madman, Maclure the perfervid Communist…. Wearing a broken down pair of slippers, his spectacles tied up with countless pieces of string, he was to be found wherever politics were discussed.’[5]

Ken Maclure adds that, ‘During his holidays, and at various times he worked in coal mines, quartz mines, worked a gold claim in the mountains for one whole year, missing a year of college [in 1933], and grew to know the working man of New Zealand extraordinarily well.’[6] This first-hand knowledge of the conditions faced by thousands of families during the Depression prompted Alex to join the NZ Communist Party, but he was an unorthodox and idealistic member, expelled more than once for refusing to conform to Party discipline.

Alex Maclure completed his course work at the School of Mines in 1936, as news of the civil war in Spain began appearing in New Zealand newspapers. Within a few months he formed the General Spanish Aid Committee, which became New Zealand’s major relief organisation for the war.

Most significantly for the young Canadian, he learned that one of his compatriots, the renowned Montreal doctor Norman Bethune, was among the volunteers who had travelled from throughout the world to aid the Republic. Maclure decided to follow Bethune’s example, but he first returned to Montreal to farewell his family during February-March 1937. To avoid alarming his parents, he pretended he was going to work in the mines of Northern Ontario. ‘As long as I can remember,’ his brother Ken later wrote, ‘he was extremely soft-hearted… It was only his strong convictions that overrode his personal feelings and drove him on.’[7]

Alex Maclure joined a group of 25 young Canadian and American volunteers led by the formidable Steve Nelson, who later became political commissar of the Abraham Lincoln Battalion.[8] They left Perpignan for Spain in the hold of a small fishing boat, but were arrested and held in a French jail along with other would-be volunteers. ‘Our jail discipline is wonderful’, Maclure told the leftwing New Zealand daily, the Grey Argus Argus. ‘When we march handcuffed through the streets, keep step and give the clenched fist salute and sometimes sing the ‘Internationale’, imagine three-quarters of the folk on the streets replying to our salute!’[9]

After several weeks in a large shared cell, the group finally reached Spain by foot across the Pyrenees. Maclure had intended to join Dr Bethune’s blood transfusion unit, but the Republican Army’s urgent need for his skills as a sharpshooter placed him, with the rank of sergeant, in charge of a machine gun unit of the MacKenzie-Papineau (‘Mac-Pap’) Battalion.[10]

In a letter to his family, he described his ‘first experience of digging in under fire with a pen-knife, and covering himself with a ground-sheet to keep the airplanes out of sight and so out of mind if possible…. in attacking a house, an Italian upstairs threw a hand-grenade at him, hitting him on the shoulder. It was only by ducking around the corner immediately that his life was saved.’[11]

In a letter to his family, he described his ‘first experience of digging in under fire with a pen-knife, and covering himself with a ground-sheet to keep the airplanes out of sight and so out of mind if possible…. in attacking a house, an Italian upstairs threw a hand-grenade at him, hitting him on the shoulder. It was only by ducking around the corner immediately that his life was saved.’[11]

Dr Bethune’s ambulance driver Hazen Sise returned to Canada and gave the Maclure family a snapshot taken in the summer of 1937 of a group of Mac-Paps, including Alex, providing entertainment for the children of the village where they were billeted.[12] A few months later, in October 1937, Maclure was killed in the fighting at Fuentes de Ebro, the first major action by the Mac-Paps. The circumstances of his death are obscure, but a letter from a fellow former student at Otago states that:

An Italian plane dropped a bomb which caused his instantaneous death. It is a very sad business but I cannot help feeling that there was a certain logical and aesthetic completeness about it. Maclure’s end was in keeping with his ideals and character, and he died I think in the way he would have chosen – while resisting fascism and advancing his cause.[13]

In November 1937 Maclure’s parents received a telegram from the Friends of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion advising that he had been killed in action on the Saragossa front. In a subsequent letter, this organisation’s secretary said, ‘When the keen edge of your sorrow has dulled somewhat, we feel certain that you will find solace in the fact that your son died while defending the ideals he cherished so deeply. His sacrifice has not been in vain for he gave his life that democracy might not perish from the earth.’[14]

At his memorial service in a Montreal church, the minister read a letter from a friend who had known Alex since childhood: ‘A brilliant mathematician, he might have gone far in the realm of finance. A talented economist, he might have become a teacher of renown. Instead, he cast his lot among the friendless, the impoverished and the oppressed.’[15]

By early 1938, the family had heard nothing more except, according to Ken Maclure, ‘for a little note of sympathy from one who had known him in the trenches and who said that even in the thickest of the fighting, whenever he was off duty, Alex might have been found off in a corner quietly reading some volume of history, philosophy or economics.’

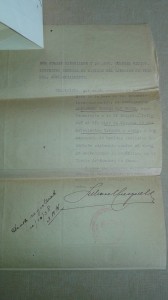

Eventually the family received death certificates from Britain’s vice-consul in Barcelona, and from a medical colonel in the Republican Army who stated that Maclure ‘died 10 October 1937 as a result of wounds received in combat sustained against the enemy while defending the Republic on the Fuentes de Ebro front.’[16]

Ken Maclure wrote the following year, ‘We have felt, often since November, that perhaps it was inevitable that Alex should have gone the way he did…. It has been truly observed, I think, that the whole world’s pain is no greater than the pain of one human being; the whole world’s courage no greater than the courage of one man.’[17]

Alex Maclure’s name appears (albeit misspelled) on the impressive memorial in Ottawa to the 1500-plus Canadians who fought with the International Brigades. Plans are now underway to place a plaque to him on the campus of Otago University, in the country where his political outlook developed, and where he is increasingly widely known and admired.

Mark Derby is a New Zealand historian. His books include Petals and Bullets – Dorothy Morris: NZ Nurse in the Spanish Civil War (Sussex Academic Press, UK / Potton and Burton, NZ, 2015)

[1] Workers Weekly 17 September 1937, p. 1. For ‘Wm. McDonald’ see M. Derby, ed., Kiwi Compañeros – New Zealand and the Spanish Civil War (Canterbury University Press, 2009), 66-70. For ‘Spiller’, see ibid., pp. 44-50.

[2] Obit., Gazette (Montreal), 11 November 1937, clipping in Maclure family collection

[3] K. Maclure letter to unidentified friend, undated but early 1938, Maclure family collection

[4] A. Clarke blogpost, https://otago150years.wordpress.com/2016/04/25/on-a-foreign-field/

[5] “A. Maclure”, Critic, 19 September 1946

[6] K. Maclure letter

[7] Ibid.

[8] See S. Nelson, The Volunteers – a personal narrative of the fight against fascism in Spain (NY: Masses and Mainstream, 1953), pp. 38-77

[9] Grey River Argus 10 July 1937, p. 4

[10] “Arnold Maclure Dead?”, Workers’ Weekly, 13 August 1937 p. 1

[11] K. Maclure letter

[12] Ibid.

[13] C.G.F. Simkin to A.G.B. Fisher, 7 June [1938?], AGB Fisher papers, MS-4304/167, Hocken Collections

[14] Secretary, Friends of the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion in Spain, 9 November 1937, Maclure family collection

[15] Memorial service record, Maclure family collection.

[16] British Vice-consul, Barcelona, death cert. dated 4 Oct. 1938; Don Julian Minguillon y de Soto, Coronel medico, Inspector General de Sanidad of the Republican Land Force, death cert. dated 4 Oct. 1938, Maclure family collection. Author’s translation

[17] K. Maclure letter

Mark,

Thanks for this great article on Alexander Maclure. Chris Brooks and I have been trying to upgrade the biographies on the Canadians and this helps pin down Maclure (aka McClure aka McLure aka MacLaren aka McLare in various news reports). We are still looking for a photo of Maclure who should be in that Mac-Pap collection with Liversedge et al. in your article.

Hi Raymond

Thanks for comment above. I am hoping that Otago University in NZ, where Maclure studied before leaving for Spain, will place a plaque to him on the campus. It would be good to have all available information and images of Maclure available if this happens, so please keep me informed of anything you discover about him.

MD