Don’t Try to Catch Me: Adam Hochschild on the First Volunteer

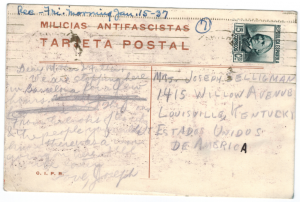

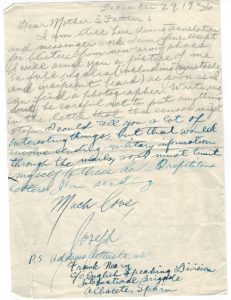

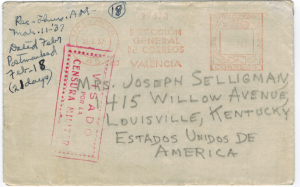

In this excerpt from his new book Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, Adam Hochschild tells the story of Swarthmore student Joe Selligman (1916-1937), the first American volunteer to join the battle for Madrid. After he left, his parents in Kentucky received an envelope mailed by a friend: “By the time you get this letter I will be in Europe. I am going to Spain. . . . I am really too excited and angry . . . to do anything else.”

One day in December of 1936, Esther Selligman of Louisville, Kentucky placed a telephone call to her son, Joe, a senior at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania. To her shock, she was told that he had disappeared.

A doodle later found among his college notes provided a clue to where he had gone. He had drawn a rough map, on which Germany, Italy, Portugal and part of Spain were colored black. It was captioned: “Europe: Again Victim of the Black Plague.” Five months earlier, the Spanish Civil War had begun, and Franco’s troops had reached the very outskirts of Madrid.

A doodle found among his college notes showed a rough map, on which Germany, Italy, Portugal and part of Spain were colored black. “Europe: Again Victim of the Black Plague.”

Joseph Selligman Jr. had been editor of the Swarthmore literary magazine and a member of the college debating team. He hoped to go on to Harvard as a graduate student in philosophy. In the home where he and his two sisters grew up, their father, a prominent lawyer who had argued cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, was a former chairman of Kentucky’s Republican Party, but their mother voted Socialist. Joe’s parents soon received a letter from him, mailed by a friend after a week’s deliberate delay, that began, “By the time you get this letter I will be in Europe. I am going to Spain. . . . I am really too excited and angry . . . to do anything else. . . . Besides, a lot of good a diploma would do in a Fascist era—and Spain seems to me to be the crucial test.”

Volunteers for the International Brigades were already arriving in Spain from many countries in Europe. The Brigades, of course, would eventually include some 2800 Americans. But the first contingent of these volunteers had not yet left the United States.

Joe Selligman had headed to Spain on his own.

Frantic, his father sent a telegram to the father of a college friend of Joe’s, Charles Crane, Jr., whose home in Montpelier, Vermont Joe had visited for Thanksgiving. just learned our son joseph left swarthmore college december third for spain stop rumored your son gone with him stop. . . . wire any information you have. But the rumor was not true, said a reply telegram from Montpelier; Charles Crane had not gone to Spain and Joe had confided nothing to the Crane family of his plans. Charles Crane’s father followed up his telegram with a letter dictated on his office stationary: “We found Joseph a very agreeable guest,” he wrote. “. . . . . after his trip up here, he wrote us a very kind and courteous note of thanks.”

Frantic, his father sent a telegram to the father of a college friend of Joe’s, Charles Crane, Jr., whose home in Montpelier, Vermont Joe had visited for Thanksgiving. just learned our son joseph left swarthmore college december third for spain stop rumored your son gone with him stop. . . . wire any information you have. But the rumor was not true, said a reply telegram from Montpelier; Charles Crane had not gone to Spain and Joe had confided nothing to the Crane family of his plans. Charles Crane’s father followed up his telegram with a letter dictated on his office stationary: “We found Joseph a very agreeable guest,” he wrote. “. . . . . after his trip up here, he wrote us a very kind and courteous note of thanks.”

In the letter to his parents, Joe added, “Please don’t try to follow or catch me or anything.” But Selligman’s father did try. He hired a private detective with international contacts, one Col. Robert M. Foster of Newark, New Jersey, and brought him to his Louisville law office. From there, seeking information about Joe, Foster fired off cables to steamship lines, passport offices and American consulates. When he knew someone he telephoned, and a legal secretary listened in on an extension, taking shorthand notes that were later transcribed. “Pick him up if you can and hold him under restraint,” Foster told the American consul in Barcelona, a friend, “and if possible send an escort with him to Paris at our expense. He is a minor.” He told the consul that even if Joe were using another name, nametags with “J. Selligman” would be on his clothes.

Selligman, Sr. sent a young law partner across the Atlantic, to try to persuade Joe to come home.

Foster found out which steamship Joe had taken to Europe and then, through a French newspaperman who did investigative work on the side, managed to locate Joe in Paris, where he had gone to enlist. Selligman, Sr. then sent a young law partner across the Atlantic, to try to persuade Joe to come home. The family also got in touch with the American ambassador to France, who was the cousin of a Louisville attorney they knew, and Joe was somehow talked into coming to the embassy to receive a phone call from his parents. Their efforts were in vain.

At the Paris labor union office where men were signing up for the International Brigades, officials turned Joe down, telling him that at 19 he was too young. Joe solved the problem by trying again, after paying $15 for the identity documents of an Irishman, Frank Neary. Once enlisted, he was assigned to the battalion of British volunteers, since no other Americans had arrived yet. He was happy to sign up under Neary’s name because, he confessed in one letter in early 1937, “an alias rather adds to the adventure-feeling, romance, etc.”

Once enlisted, Joe was assigned to the battalion of British volunteers, since no other Americans had arrived yet.

In Paris, newly-arriving volunteers were taken to the Gare d’Orsay on the banks of the Seine. Under its high, vaulting glass roof, they boarded what was informally known as the “Red Express” for the Spanish border. As the train sped through France, men sang the “Internationale” in half a dozen languages, while the farmers and railway track workers they passed made the clenched-fist Popular Front salute.

Another letter home from Joe just after Christmas mentioned proudly that he was growing a beard and mustache. He included a photo of himself in uniform, with a beret. “Quit worrying,” he wrote his family. “I am in no danger.” He would stay out of the line of fire as a driver or an interpreter—he knew French, German, a little Spanish and “also I am learning to speak British.” Selligman’s father, not reassured, wrote to Louis Fischer, who was covering the war for the Nation, pleading with him to make inquiries about his son. He continued to try to enlist the help of American diplomats. Joe again wrote his parents, “For God’s sake, quit trying to catch me.”

Another letter home from Joe just after Christmas mentioned proudly that he was growing a beard and mustache. He included a photo of himself in uniform, with a beret. “Quit worrying,” he wrote his family. “I am in no danger.” He would stay out of the line of fire as a driver or an interpreter—he knew French, German, a little Spanish and “also I am learning to speak British.” Selligman’s father, not reassured, wrote to Louis Fischer, who was covering the war for the Nation, pleading with him to make inquiries about his son. He continued to try to enlist the help of American diplomats. Joe again wrote his parents, “For God’s sake, quit trying to catch me.”

At the British Battalion’s training base, hastily improvised in a village called Madrigueras, Joe Selligman and his fellow volunteers were each issued brown corduroy trousers and a jacket too light for the January weather, a thin blanket, bulky ammunition boxes attached to a belt, and a helmet. “In spite of its dashing appearance,” wrote Jason Gurney, a London sculptor in the battalion, “it was made of very thin metal and was quite useless as a protection against anything more lethal than kids throwing stones.”

There were no rifles or bayonets.

Joe and his British comrades trained for six weeks, but only a day before they were sent to the Madrid front did a shipment of Russian rifles finally arrive. Ominously, the same day word came that Málaga, on Spain’s south coast, had fallen to Franco’s troops, heavily supported by Italians manning tanks and armored cars sent by Mussolini.

For three months now, Franco’s forces had besieged Madrid, and he now planned a new offensive in which Nationalist troops were to encircle Spain’s ancient capital. The first assault was to cross the Jarama River south of the city and then strike towards the northeast to cut the road from the Mediterranean port of Valencia, the crucial lifeline that supplied Madrid with arms, ammunition and food.

In the first few days of the offensive, the Nationalists managed to kill or wound well over 1,000 Republican soldiers and come dangerously close to the Madrid-Valencia road. Republican commanders rushed new troops, principally the International Brigades, to defend the road’s endangered flank. It was here that the British Battalion was sent, ordered forward through rain-soaked olive groves under heavy Nationalist artillery fire. The men had finally been given rifles, but had only been able to shoot ten practice rounds apiece. Nonetheless, they were relieved to have real weapons at last. “We began to feel like men again and something of the spirit of the crusade came back into us,” Gurney wrote. “Had I realized that one half of our company would be dead within the next twenty-four hours, I might have felt differently.”

On February 11, 1937, Gurney, Joe Selligman, and the rest of the British Battalion marched to the front line. In the battle for Madrid, Selligman would be the first American to go into combat.

On February 11, 1937, he, Joe Selligman, and the rest of the British Battalion marched to the front line. In the battle for Madrid, Selligman would be the first American to go into combat.

***

The next day dawned clear and cold. As Franco’s artillery boomed and fighter planes dove and wheeled in a dogfight overhead, at the stone farmhouse they had taken over as headquarters the British received orders to move forward. The landscape into which they advanced was a lovely one of pine, oak, cypress and olive trees scattered across a plateau and valley, carpeted here and there with fragrant marjoram and sage. For a moment, positioned on hills with a view of the countryside, it was possible to feel part of a great international effort, for a unit of French and Belgian volunteers was to one side of them. “We looked magnificent, we felt magnificent,” remembered one battalion member, “and we thought that if only our colleagues back home . . . could see us now, how proud they would be.”

But “not even the Brigade staff,” according to Gurney, “possessed maps. . . . and they were dependent on reports arriving in four different languages.” Furthermore, the British Battalion’s machine guns—most of them prone to quickly jam—required four different kinds of ammunition, and its rifles a fifth. And some belts of bullets, it turned out, didn’t fit any of the machine guns. One advantage the British theoretically had was that part of their position was on higher ground. When a three-hour Nationalist artillery barrage began, however, they quickly christened the place Suicide Hill. They had had no training in digging trenches and foxholes–and there were no shovels.

“Not even the Brigade staff possessed maps, and they were dependent on reports arriving in four different languages.”

Then came an attack by thousands of Moors, “their uniform,” wrote Gurney, “covered by a brownish poncho blanket with a hole in the middle which appeared to flutter around them as they ran. . . . It was terrifying to watch the uncanny ability of the Moorish infantry to exploit the slightest fold in the ground which could be used for cover. . . . It was a formidable opposition to be faced by a collection of city-bred young men with no experience of war, no idea of how to find cover on an open hillside, and no competence as marksmen.” The fighting was ferocious; at one point the advancing Moors came within 100 feet of the British position. The superior number of Nationalist troops, and the relentless pounding of German artillery took a terrible toll, against which a stream of exhortations from Brigade headquarters in French and Russian was little help.

The shelling cut the battalion’s telephone lines, and so Joe Selligman was assigned to be a message runner. As the day wore on, the toll continued to mount. By evening only 125 out of 400 British riflemen had not been wounded or killed. “Everywhere men are lying,” remembered one survivor. “Men with a curious ruffled look, like a dead bird.”

Near dusk, Gurney unexpectedly came upon a group of wounded. They had been carried “to a non-existent field dressing station from which they should have been taken back to the hospital, and now they had been forgotten. There were about fifty stretchers all of which were occupied, but many of the men had already died and most of the others would die before morning.” The experience seared him. “I went from one to the other but was absolutely powerless to do anything other than to hold a hand or light a cigarette. . . . I did what I could to comfort them and promised to try and get some ambulances. Of course I failed, which left me with a feeling of guilt which I never entirely shed. . . . They were all calling for water but I had none to give them.”

One British Battalion member who may well have been in this group of wounded was Joe Selligman, for during the day’s fighting he received a bullet in the head from the attacking Moors. Eventually evacuated by mule—a jolting nightmare for a soldier with a head wound–he ended up in a hospital near Madrid.

When Joe’s family heard that he had been wounded they immediately began sending panic-stricken messages to American officials in Spain and Washington. urgently request effort be made to remove him further from fighting zone or into france if possible and his condition permits, his father telegraphed Secretary of State Cordell Hull, i will bear all necessary expense. On what happened next, the record is contradictory. A flowery letter from Harry Pollitt, chief of the British Communist Party, assured Mr. Selligman that young Joe had been “taken to hospital where he was given every available treatment, and expressed his own appreciation of the kindness and solicitude of all those who came in contact with him.” But a British survivor of the battle, a fellow message runner, reported that Joe never regained consciousness. Whatever the case, within two weeks of being wounded–or possibly less; no medical records survive–he was dead.

Another letter from Pollitt spoke of “Comrade Selligman”; Pollitt also said how well liked Joe was, talked of “the sublime self-sacrifice of so many fine sons such as your own,” and said that Joe had been “buried with full military honours.” But when his grieving father now asked American diplomats to see if Joe’s body could be sent home, again offering to pay all expenses, a telegram from the secretary of state suggested a different story, saying that the remains cannot be removed for reburial as he was buried with some seven or eight men which would make individual identification impracticable. The secretary was actually softening news received from an American diplomat in Spain. Two days earlier, he had cabled Washington that at the time of Joe’s death there were some 250 other soldiers whose bodies had to be removed from the hospital and buried at once.

Unable to recover his son’s body, Joe’s father asked the State Department’s help in sending home any of his belongings. All that could be found, however, fitted into a single envelope: two billfolds containing a Kentucky driver’s license and an i.d. card from the Swarthmore College gym.

***

Some letters discovered only recently add a poignant coda to the story. The college friend he had visited in Montpelier, Vermont over the Thanksgiving just before his departure for Spain, Charles Crane Jr., was the son of an insurance executive. The two young men shared a passion for philosophy. Shortly after Joe Selligman visited the Crane family, Crane, who had graduated from Swarthmore the previous spring, also attempted to volunteer to fight in Spain. But he got no farther than New York City. As he put it cryptically in a letter, “I was apprehended by my father . . . and returned to Montpelier.” More details we do not know.

Two months after the Thanksgiving visit, young Crane’s father wrote again to Joe’s father. His letter formally began, “Dear Mr. Selligman”, but was handwritten on lined paper. It reported the news that Charles Crane Jr. had just committed suicide. “From youth up he had been somewhat of an anxiety to us,” his father wrote, “because of his too-serious interest in ‘the purpose of life’. . . in mockery of this cock-eyed world he has quit it—a brilliant, companionable son—leaving us crushed.” A note at the bottom added, “Excuse the paper. Written in bed.”

Two months after the Thanksgiving visit, young Crane’s father wrote again to Joe’s father. His letter formally began, “Dear Mr. Selligman”, but was handwritten on lined paper. It reported the news that Charles Crane Jr. had just committed suicide. “From youth up he had been somewhat of an anxiety to us,” his father wrote, “because of his too-serious interest in ‘the purpose of life’. . . in mockery of this cock-eyed world he has quit it—a brilliant, companionable son—leaving us crushed.” A note at the bottom added, “Excuse the paper. Written in bed.”

Selligman Sr. immediately wrote back a heartfelt letter of sympathy, from one father to another, but still addressed “My dear Mr. Crane.” Of Joe, in Spain, he said, “We shall not write him of Charles’ death. Knowing how devoted they were to each other, we would not want Joseph to have the shock of this news when he is alone so far from home.”

The letter is dated February 12, 1937—the very day that young Joe Selligman received his fatal bullet wound. Before either family got this news, Mr. Crane replied, now back in the office and dictating to his secretary, to thank Joe’s father, saying that “somehow I got more comfort out of your letter than I have out of any of the many messages we have received.” He added, about his own son: “I only wish Charles had started off to Spain or something that would have kept his mind away from self-destruction.”

Soon after this, Selligman, Sr. received the news of Joe’s death, and wrote to inform Crane, ending his letter, “We shall face the years to come with such grim courage as we can summon . . . hoping also that for the betterment of the world such idealism as our two boys cherished may not perish from the earth.” For several months, the two bereaved fathers in Louisville and Montpelier continued to exchange letters, always on office stationery, always with the sets of initials showing they were dictated to secretaries, always “Dear Mr. Crane” and “Dear Mr. Selligman.”

“I hope that our family may sometime meet yours,” Crane wrote to Selligman at one point, “and talk of many things which are hard to put into our letters.” They never managed to do so.

Adapted from Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 by Adam Hochschild, to be published in March by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. The author wishes to thank Joseph Selligman’s sister, Lucy Selligman Schneider and his niece, Lucy McDiarmid. The family has donated Selligman’s letters and related materials to the ALBA archives at New York University’s Tamiment Library.

Presentation of Adam Hochschild’s new book

Spain in our Hearts, Americans in the Spanish Civil War

March 31, 2016. McNally Jackson Books, New York