The Commissar and The Good Fight – by Saul Wellman

Editor’s note: At the initiative of ALBA board member Chris Brooks, who maintains the online biographical database of US volunteers in Spain, in 2015 the ALBA blog regularly posted interesting articles from historical issues of The Volunteer, annotated by Chris.Over the next three months, Blast from the Past postings showcased articles about the American volunteers who served in the Artillery. Many of these articles ran in The Volunteer during Ben Iceland’s tenure as editor. Iceland, who served in the Artillery, recruited several of his fellow artillerymen to document their experiences. Iceland also shared his own experiences in a series of articles he originally wrote in the early 1940s. Together these articles shine a light on some lesser known American volunteers. We now extend the series by posting some additional articles which were not included in the original series, though they are fascinating in their own right.

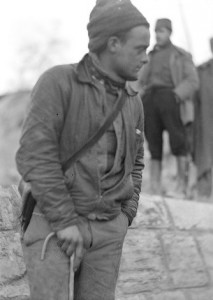

Saul Wellman, Political Commissar of the MacKenzie-Papineau Battalion, February 1938. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA Photo 11; ALBA Photo number 11-0952.

The Commissar and The Good Fight

by Saul Wellman

[This article was part of a larger article VALB Vets Speak at the Smithsonian.]

The Good Fight is a fine film. I have only one quarrel with it. At one point, for example, the film’s commentator refers to a strange breed of officer, the Commissar, whose only job was to make speeches. The film thus promotes the widely held notion that the Commissar was a Communist martinet, a political bureaucrat detached from the dangers of war, protected from it deprivations, and isolated from the rank and file. As a Commissar of the Canadian Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, I can assure you that was not so. This breed of officer made a unique contribution to the defense of the Spanish Republic.

The Spanish Commissariat of War

The Spanish Commissariat of War was created by the Spanish Republic four months after the Franco rebellion began. The idea came from the French Revolution. The Paris Convention created the first political commissariat at a time when a barely organized French revolutionary government faced the task of defending itself against the armed reactionary powers of Europe. One hundred fifty years later, the Spanish Commissariat of War was created by the Spanish Republican Government. The army had rebelled, taking with it weapons, equipment, supplies, its experienced officers and disciplined soldiers.

The Republic had available an enthusiastic, patriotic, supportive populace but totally untrained in the necessary arts and skills of warfare. It was too quickly learned that it would not long be able to survive against the mercenary Spanish Foreign Legion, the Moorish Army of Africa, Mussolini’s 50,000 man Corps of Voluntary Troops, and Hitler’s Condor Legion without a capable army to defend itself. Lacking the necessary structure, skills, training and discipline it borrowed an idea from the revolutionary government of France which had found itself in the same condition 150 years earlier. It set up the Commissariat as the agency of the Spanish government within the War Department. The Commissar was a military officer whose rank paralleled that of the military commander. His role was outlined in a 1938 document published by the Commissariat of War.

Our role of the Commissar was “…to inspire their unit with the highest spirit of discipline and loyalty to the Republican cause and establish a feeling of mutual confidence and good comradeship between Commanders and men.” The Commissar was also to be “…an educator in the broadest sense of the word, using every opportunity to clarify all political issues that arise.” In other words, the Commissar’s mission was to fill the void caused by a lack of training, experience, weapons know-how, [and] discipline – the lack of ability to received orders and carry them out. You must remember that many of the rank and file in the International Brigades had been political activists in their own lands. The American volunteers were coming from the battles of union organizing, from the unemployed demonstrations and strike struggles. They were not prepared, had not been trained, and had never before asked to accept the discipline of warfare. I won’t claim that all commissars fulfilled this role equally well. Some, like George Watt, were dearly loved. Others were intensely disliked. Because of my natural abrasiveness, I fell somewhere in the middle but we all had the same tasks. Urging men out of protecting trenches into the face of enemy gun fire might also include kicking ass. Reacting to the ever present lice and filth might require contriving a homemade sauna and shower or finding clean clothes.

I was once described as a cross between a Commissar and a Mother Hen. The Commissariat of the Spanish Republic expected the Commissar to be a Mother Hen:

“The Commissars’ work extends to the smallest details that contribute to the material well-being and comfort of the men. He is not a cook, but sees that the food is prepared as well as possible; he is not a quartermaster, but he worries about clothes and supplies; he is not a doctor, but he worries about health hygiene and sanitation… He seeks to develop fraternal relations between the troops and the population.”

In carrying out this charge I recall once spending two weeks trying to track down American cigarettes for my men to replace the harsh French Gauloise issue – only to be refused those Lucky Strikes by no one less than the Brigades Inspector General – Luigi Gallo.

Oil for Our Diet

These mundane tasks were in fact vitally necessary to keep together an army made up of unskilled beginners who sometimes were awkward fumblers; foreign volunteers who often though of picking up and going home. Let us focus on two

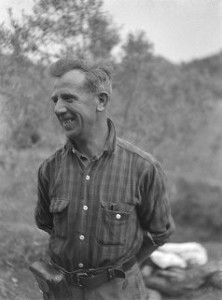

Joe Gibbons, Mackenzie-Papineau Estado Mayor, April 1938. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA Photo 11; ALBA Photo number 11-1300.

examples of the commissar’s task in greater detail.

After the terrible battle of Teruel, we were bone-tired. The battalion needed rehabilitation and rest except that there were no facilities and there was no escape from the front. Food was in short supply. Our diet consisted entirely of dried cod fish, a monotony not even broken by the perpetual garbanzos or, as we knew them on the Lower East Side of New York, “Haysa arbas.”

Then our skin began to dry and crack. Dr. Hene, the battalion doctor, said we lacked oil and fat in our diet. But in a country impoverished by war, where were we to obtain such food? Someone thought about the tiny independent country – Andorra – up in the Pyrenees, mid-way between France and Catalonia that had not been touched by the war but where the people might be sympathetic. Maybe we could get oil there. That would be a 2 or 3 day trip. We had some money but no idea how much it would buy. And we had no extra transport to release. I discussed the venture with Joe Gibbons, a comrade in the first company. Joe offered to take two other guys, go into Barcelona, get a truck by hook or by crook, go north to Andorra, and try his luck. I got him the necessary travel papers and he was off. Four days later he returned. No words were exchanged except a wink and a red front salute as he passed me a handful of nuts to replenish our depleted bodies.

My purpose in telling you this story is to convey to you why the Commissars were so important. We did not have a sophisticated well-organized, tightly run military bureaucracy, set channels through which requests could be forwarded, and through which requests could be forwarded, and through which needs could be met.

The Commissar provided the fingers needed to plug the holes in the leaky Republican dike. The mission to Andorra was not processed thorough a military/political hierarchy. It was improvised and implemented in the field. I had the authority to initiate it, approve it, and to obtain the necessary papers. The rest required luck, ingenuity, and most important, the good will of the Andorran people who sold us their nuts.

El Muleton

Let me turn now to the idea that the commissar sat in a safe office studying Marx and Lenin, theorizing about the politics of revolution, and turning out inspirational propaganda urging men into battle. Again I quote from the Commissariat’s vision:

“The Commissar cooperates closely with the Military Commander at whose side he is appointed. He participates in an advisory capacity in the decisions of the military command… orders and reports are signed jointly by the Commander and the Commissar. At all times, the Commissar sets a personal example to the Volunteers of the rank and file. In action, he is found where his personal example and influence is most decisive. He is the first to advance and the last to retreat.”

Were these just words, or did we try to live up to this ideal? I think there is ample evidence that most of us behaved in a manner we can be proud of, I personally participated in 5 major battles, at Fuentes de Ebro, Mas de Las Matas, Teruel, the Retreats and the re-crossing of the Ebro. I was wounded in that last action in August, 1938. To give you some idea of what we did, let me tell you the story of a fortified hill called El Muleton.

The battle began in mid-December, 1937 when the Republic launched a daring attack against what had been considered impregnable Teruel. Three columns succeeded in entering the town. Franco immediately counter-attacked by moving ten thousand Italians and 50,000 additional insurgent troops from the Guadalajara front and other Aragonnese sectors. New Italian batteries were dispatched and the skies above Teruel were blackened by German and Italian planes.

The 15th Brigade was dispatched to Teruel arriving at its outskirts in a freezing blizzard. The men tumbled out of the trucks and tried to bed down for the night in shell-shattered houses at the edge of town. During the next month, the Franco counter-offensive continued and the Brigade was slowly pushed back. By the 16th of January Franco’s counter-offensive had passed almost to the gates of Teruel and the entire XVth was dispatched to establish defenses on its outskirts. The third company of the Mac-Paps found itself on a hill south of Teruel under fire from the superior artillery and aviation of the Insurgents. The hill was called El Muleton.

At battalion headquarters we were getting word of the precariousness of their position; of the accuracy of the bombardment; of the Moorish cavalry attacks they had beaten back. Our comrades were having difficulty digging their fortification positions more deeply because the chalk composition of the trenches and machine gun pits was so weak that the German artillery barrage destroyed them as soon as they were dug. At moments the machine guns and rifles were inoperable since the chalk dust continually clogged the mechanisms. After a burst of 20 bullets the mechanism would jam; a cartridge would wedge tightly and uselessly in the firing chamber, held rigid, causing the entire gun to jam. There were no trees or vegetation left on El Muleton. The surface was almost bare and Teruel was visible in the distance.

Harry Schoenberg, Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion, December 1937. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA Photo 11; ALBA Photo number 11-1285.

In time of combat the commissar was assigned to one of the units, typically one that was in trouble. And so Harry Schoenberg, battalion adjutant, and I jointed the third company defending El Muleton. When we reached the 3rd company position and found the company commander, we didn’t need a report. The end was not yet in sight and the nightmare would last for another two days. Lionel Edwards, the company commander, and I talked but I can assure you I wasn’t making political speeches. He needed help! Help to carry ammunition forward. Help to bring the wounded out. Help to deepen a machine gun pit. Help to clean or wipe a jammed machine gun. Help to find food or water. So, that’s what Harry and I did. We carried out the wounded, dug pits, brought food and water, fixed jammed machine guns, and, as our numbers dwindled, we fixed them and fired them. As the fury of the artillery attack increased, our weapons became more unreliable.

That afternoon I sent a message to battalion headquarters that said something like: “Send someone up her who knows more about things than I do!” Organizing picket lines or going to demonstrations hardly prepared me for this. I was exhausted and overwhelmed. Comrades were dying all around me. We were holding but for how long? Later I asked Nilo Makela, the machine-gun company commander, about the message. He said “Yes, we got it, but you knew as much as any of us did.”

Finally, the end came. Our machine guns were blown to pieces. We were under fire from nearly every side and no more reinforcements or resupply could reach us. Our only arms were rifles. In a company of 50, 45 were dead or wounded. It was time to retreat.

I hope you can understand why I take exception to the caricature of the Commissar offered in this film. Casualties among Commissars were higher than casualties among Commanders, which were themselves higher than casualties among the rank-and-file.

The uniqueness of the commissar system has often left it open to ridicule and attack by its detractors. But we must remember: An army in rebellion, supplied by two powerful nations, confronted by untrained people’s militias usually achieves a quick success. That it took the Insurgents 30 bloody and hard-fought months can only be explained by unique and innovative responses of the Spanish people. The commissar system was one such response.

Thank you, Chris, for digging this story out. There is a wonderful photo of a smiling Sauly Wellman, Lou Bortz, Bill Skinner and Harry Schoenberg after Teruel where the four of them had been given commendations for their actions at Teruel (ALBA 11_0874).

People overlook the fact that perhaps 1/4 of the Commissars were not Party members and viewed their roles as the ombudsman for the troops, nagging superiors for the lack of supplies that were needed. Wellman said it eloquently here.

[…] “The Commissar and The Good Fight – by Saul Wellman.” The Volunteer, 16 Sept. 2018, albavolunteer.org/2015/12/blast-from-the-past-revisited/. […]