The Shelters of the Civil War

The first thing you see as you approach the Civil War Shelters Museum on Gisbert Street in Cartagena are the trees growing out of the mountainside. Their unusual network of thick, exposed roots pushing out of the ground suggests that these ancient trees might have been around since the Bronze Age, witnessing Hannibal as he led his army and war elephants across the Pyrenees in battle. While that may be only speculation on my part, what they undoubtedly did pay silent witness to was the tragedy of the sustained and massive bombing of this city by the fascist allies of Franco during the Spanish Civil War in 1937.

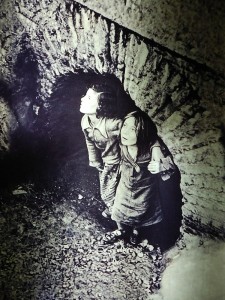

A visitor to the museum can hear the surviving human eyewitnesses, who were children at the time of the war, in their recorded testimony on display in one of the preserved air raid shelters, opened to the public since 2006. In the videos, one man shares his memory of how, in an attempt to thwart the ruthless attacks, the townspeople worked together to fill a field outside of Cartagena with poles rigged up with lights, which were switched on when warning of an approaching aircraft was received. They then switched off the lights in the town, diverting the bombs to fall on the deserted area, thus saving lives and homes. These videotaped interviews, artifacts, posters and film archives have been collected in a restoration of one of the many air raid shelters in the system of tunnels and chambers dug out by local miners throughout the city.

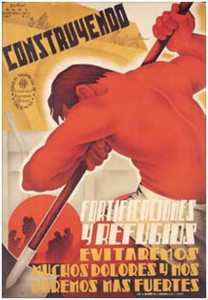

Passive defense poster: “Building Fortifications and Shelters, We Will Avoid Much Pain and Make Ourselves Stronger.”

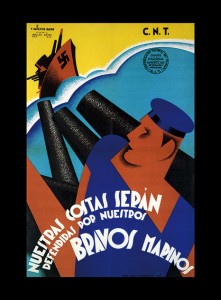

The aerial bombardment of the civilian population, to which the videos refer, were part of Franco’s strategy to terrorize and demoralize the people in this Republican area, with the aid of his German and Italian fascist allies, while also training the Condor forces and testing out the weaponry that they would go on to use in the Second World War. The port of Cartagena, a primary stronghold as the site of the Republican naval forces and potential point of entry for aid, was therefore one of the hardest hit cities during the Spanish Civil War. As the museum documents, on November 25, 1936, they endured a four hour aerial assault, which caused raging fires throughout the city. The people of Cartagena responded with both passive and an active, military, defense in the form of anti-aircraft guns which were able to force the planes to fly at greater heights. The passive defense is what is recorded so touchingly in this museum. A lift in the museum takes you up for a panoramic, aerial view of the port and it’s naval center, still in use today, in order to see what made the city a prime target.

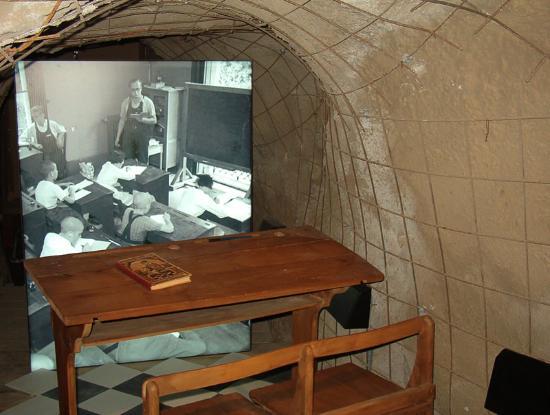

This shelter on Gisbert Street, one of the largest, was capable of holding 5500 people. Galleries in the museum recreate the everyday life they made an effort to continue in the shelters. In one such vignette exercise books and school desks are placed in front of a photographic backdrop of children attending underground classes during those dark days. Viewing these displays, you begin to understand the totality of the loss that even the survivors endured, as the newly established programs of the Republic and the hard won gains they represented were obliterated along with the physical structure of the city. By showing how everyday life was affected by the bombing, the museum does not allow us to forget the brutality of the fascist attacks on the civilian population.

One way the museum conveyed this so effectively was by displaying side by side newspaper accounts of the bombardment from the Nationalist and Republican perspectives. My guide, IBMT Ireland Secretary Manus O’Riordan, pointed out the contrasting way it was reported at the time. The mendacious fascist announcement boasted of the ease with which they demolished their strictly military targets, while the Loyalists published the damage done to schools, hospitals and the civilian loss of life.

While the museum details with great sensitivity the destruction, privation and hunger visited upon the city, one of the last to surrender to the fascists, the present day children’s drawings in the last section form an eloquent plea for peace.

Nancy Wallach is a member of ALBA’s Board of Governors and a daughter of Abraham Lincoln Brigade Veteran Hy Wallach.