A Train Is Bombed – by Ben Iceland

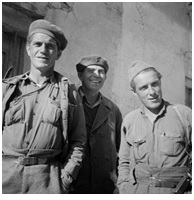

Joseph Dougher, Commissar, Mackenzie-Papineau, Company 3, Albert Harris, Brigade Intendencia, and Wally Sabatini, Political Commissary Mackenzie-Papineau, Company 3, October 1937. The 15th International Brigade Photographic Unit Photograph Collection; ALBA Photo 11; ALBA Photo number 11-0728.

Editor’s note: At the initiative of ALBA board member Chris Brooks, who maintains the online biographical database of US volunteers in Spain, the ALBA blog will be regularly posting interesting articles from historical issues of The Volunteer, annotated by Chris.Over the next three months, Blast from the Past postings will showcase articles about the American volunteers who served in the Artillery. Many of these articles ran in The Volunteer during Ben Iceland’s tenure as editor. Iceland, who served in the Artillery, recruited several of his fellow artillerymen to document their experiences. Iceland also shared his own experiences in a series of articles he originally wrote in the early 1940s. Together these articles shine a light on some lesser known American volunteers.

A Train is Bombed

Ben Iceland

[Originally published in The Volunteer, Volume 5, Number 2, June 1983.]

The fascists were driving to cut Spain in two, and we kept retreating to the sea. We kept setting up our guns in one position after another, hoping that the lines would be stabilized somewhere, anywhere. Nobody knew where the enemy was, and some days we didn’t even set up our guns, fearful of being cut off. The roads were full of refugees and demoralized troops. Once we barely got out of a town as some enemy tanks came clattering in, and three of our men were killed by the machine gun fire of the tanks before they could mount the trucks. They were Hungarians.

All day their planes filled the sky, and rarely did we see one of our own. We were the only Antiaircraft battery in action – the French battery having lost its guns at the start of the retreats outside of Belchite. Of the Americans, only Crosby was missing. Hawkins whose nerves were shot, and who could not stop trembling, had been invalided to the base at Manises for reassignment.

Finally, towards the end of March, we stopped retreating for a couple of days, and set up our guns on a hill near Gandesa. We were grateful for the respite, and we didn’t know whether our lines were holding, or whether the enemy was too wearied to continue his offensive. The food came up hot, and there was even a ration of French tobacco. While we were there, we saw about a dozen truckloads of men heading west for the front. The men in the trucks were wearing blue coveralls with red bandanas and they were actually singing. We surmised they were workers from Catalonia sent to build fortifications to help stem the retreat. The men with their coveralls and bandanas and singing reminded me of the newspaper pictures I had seen back home in the early days of the war when the worker’s militia had been formed.

“The poor bastards,” muttered Louie Roberts cynically. “We need planes and tanks, not anarchists from Barcelona.”

Early in the morning of the third day, a truck pulled up to our position, with reinforcements for our battery. Nobody had previously told us about this, and John, our Czech-American section leader, explained to us that these were men returning from hospitals and other outfits. We English-speaking were to be sent back to the base at Manises for reassignment with American outfits. He did not know what outfits, and though we plied him with questions, he knew nothing.

We had been with the battery for about two months, and sometimes there had been difficulties because of language and attitudes. In the time we had been with the Czechs we had had no English reading material, and not a letter from home had reached any of us. So while I was glad to be relieved, still it was with some sadness and regret that I left.

At Manises I was examined by the same Chinese doctor who was attached to the Antiaircraft units. It was the same doctor who had given us our first-aid kits when we were originally assigned to the Czech outfit at Teruel. A couple of days before our stay at Gandesa I had been hit in the soft underpart of my knee by a tiny shell fragment. At the time it felt like a sharp pin prick, and I thought nothing of it. Afterwards it became painful, and I went to our battery practicante [medic]. The blood had already congealed, and he washed it out, and applied a blackish-looking ointment, and then bandaged it. But the pain continued, and when I went to the practicante again, I noticed that the hole was getting larger and was running pus. He assured me it was getting better, and applied the same ointment again. But it didn’t get better, and when I questioned the efficacy of his ointment and suggested it might be better for a doctor to look at it, he muttered to himself in annoyance. The only word I could make out was “Amerikansky” and I imagined he was saying something derogatory about Americans.

The Chinese doctor washed out the hole which was still festering, and this time applied a white ointment, bandaged it, and then gave me a salvo-conducto [travel orders] for the International Brigade hospital at Denia.

I caught a truck to Valencia, and from there took the train to Denia. The hospital had been a private villa before the war. The government had requisitioned it when the rebellion broke out, and there were conflicting stories about the fate and whereabouts of its owner. The grounds were beautifully landscaped, and it was surrounded by luxuriant fields crisscrossed with irrigation ditches, and growing many varieties of vegetables – especially onions, garlic, tomatoes and spinach. A pink, sandy road led to the sea, only two kilometers away.

There were quite a few Americans at the hospital, including some who had been wounded during the retreats. Basic Industry Hawkins was there, and we were overjoyed to see one another. I had to tell him everything that had happened since he had left the battery. He was still a bit shaky and very worried about the possibility of the fascists cutting through to the sea and leaving us stranded in the south. All the soldiers at the hospital were worried about the situation at the front. Very little news had been coming through, and the very scantiness of the news heightened their alarm. They wanted me to tell them whether the lines were holding, and wanted to know what was happening to the Lincolns, and what had become of some of their buddies. I knew as little as they did, and could furnish neither encouragement nor news. Then some more Americans, mostly with leg wounds, appeared at the hospital. They painted a much gloomier picture of defeat and retreat and utter disorganization. Bill Martinelli, one of the new arrivals, told us how they had mistaken an Italian tank for one of our own, and how the tankist had closed the hatch and started firing, wounding some of the men, including himself, and then crushing some of the wounded who were lying helpless on the road. There was little hope that the lines would hold.

It was beautiful along the Mediterranean in early Spring. Those of us who were ambulatory used to walk to the sea every day. There was a little café with a colored tile roof on the beach where there was nothing to eat. There was some sour vino, and we would drink the stuff and were always a little stewed. All day long the sun shone and the sea was smooth and colorful, from blue to green to purple as far as the eye could see. There were fishermen’s rowboats drawn up on the strand, and we eyed them, and some of the guys talked about the possibility of rowing to Africa in an emergency.

HE KNEW DIALECTICS

No one really knew how close the fascists were to cutting Spain in two, and the military situation was ever in our thoughts and conversations. The professional optimists said the fascist couldn’t get through, and even if they did, it would be better for us as our lines would be shortened. Gilbert[1], one of the optimists, even tried to illustrate his line “shortenings” by drawing a crude map on a piece of paper.

“If you know dialectics,” he said, “you’ll know the fascists can’t make it.”

Walters who had just come from the front with an arm wound, shook his head disgustedly, and interrupted him: “To hell with your map and dialectics; the fascists have artillery and avion which works better than our dialectics. They’re bound to get through.”

And a few days later, Gilbert fucked off to Valencia, and then when we heard that he had somehow reached Barcelona, Walters[2] drily remarked: “That coño knew dialectics – we didn’t.”

The food at the hospital was pretty bad – usually a thin watery soup with something like spinach floating around in it, or pebbly lentils with an occasional piece of burro meat or bacalao that hadn’t been soaked properly. There was no tobacco, not even the god-awful Spanish pillowslips. So we spend a lot of time hunting for butts and griping about the food; and of course we worried about what was happening at the front.

Call-A-Meeting Joe, a burly miner from Pennsylvania, organized a delegation of the English-speaking to try and get some information from the hospital authorities. Joe was a real take-charge guy, with a loud voice and an officious manner. At the hospital there were two doctors in charge, plus an Italian political commissar. One of the doctors was an Austrian who was rarely seen at the place. The other doctor was rarely seen at the place. The other doctor was a good looking dark-haired Polish woman in her late thirties who seemed to do all the medical work that needed to be done. It was she who decided who was “apto por el frente, [capable for the front]” and who was not yet “apto.” She often had with her a romantic-looking mustachioed American who had some sort of function to do with culture and music. While I was in the hospital there was not much culture or music. We had nicknamed him “Don Juan,”[3] and we all envied him and we used to joke among ourselves about what he was being stamped “apto” for. Although only a private, he had the most immaculately tailored uniform, together with shiny leather boots, and a rakish military cap. He avoided us.

We walked across the green, luxuriant fields through orange and lemon groves and apricot orchards, to the main villa on the coastal road. The earth seemed so rich and fruitful, and yet we were hungry. There were about a dozen of us, with Call-A-Meeting Joe, looking determined and angry, in the van. Next to him walked Hicks, tall and exceedingly blond, and with a slight limp. Hicks came from Wisconsin. Back home he had at one time been a college instructor – a least he said so – and active in the radical movement. He had a glib tongue, and was always mentioning his close relationship to leaders of the American Communist Party. Hicks had come to Spain early, and been assigned first to an anti-aircraft outfit, and then to the Auto-park. Nobody knew why he was at the hospital; certainly it was not for any wound. But he was completely demoralized. His filthy uniform hung from him in tatters, and his testicles peeped out of a hole in his trousers – trousers which extended to way above his ankles. He never combed his hair, and rarely shaved, and was always scratching his lice. Before we got to the villa, Bill Martinelli said he wouldn’t proceed any further with Hicks. He was ashamed to be seen with him. Hicks, started to curse him, and Martinelli, who was at least a head shorter than Hicks, hit him in the belly with his fist. Hicks doubled up and sank to the ground, and there were tears in his eyes when we resumed our walk, with him following.

“I hate the bastard,” said Martinelli – “always talking about being a college professor. Why in hell can’t he clean up?”

Martinelli had a fetish about cleanliness. He was always washing himself, and the sight of Hicks would set him to muttering. He was a sailor out of San Francisco – an oiler. He liked to tell us stories about the waterfront when the union was first being organized, and he had been the leader of a “Beef Squad” to take care of scabs.

We continued our walking, and behind us was Hicks, silent now, with long arms extended from his sides, and looking like Icabod Crane in the glaring sunshine. Kelly[4], a goodhearted lumber worker from Vancouver, felt sorry for Hicks, and joined him. Kelly would amuse us with his stories of the Irish rebellion. They were different always, depending upon how much he had had to drink.

When we arrived at the main villa, only the Political Commissar, a heavy-set Italian in a swanky uniform, was there to speak to us.

“This guy’s never been to the front,” whispered B.I. Hawkins. Hawkins didn’t really know whether he had or hadn’t been to the front.

When we told him why we had come he shook his head and said in a mixture of Spanish and Italian:

“What’s the matter with you Americans? There’s no need to worry. Maybe things at the front are not going so well, but they’re bound to get better. France is opening the border. Diciplina, comrades, disciplina.”

One of the guys growled:

“The pig’s ass – France is opening the border! I’ve heard that one for a year now, and the border is still closed. What do you expect from the Socialist Leon Blum? He’s scared shitless.”[5]

“Why isn’t something being done to get us out of here, to get us up north?” asked Call-A-Meeting Joe. “We heard that all the Internationals are being evacuated to Barcelona. What about this hospital? We’re not much good down here.”

The Commissar knew as little as we did, and for all his spluttering, we could see he was as worried as we were.

DENIA IS BOMBED

We walked back across the green fields, and the bare mountains rising behind the road were purple against the blue sky, and there were the ruins of the Moorish castle (or was it Roman) on the hill looking everlastingly across the sea, and we were hungry and thinking of home.

There were some ships in the small harbor of Denia, and that night the Capronis came from Mallorca and dropped their bombs. They kept coming back in the moonlight, and for many hours we could hear their droning, and see the flashes when the bombs exploded. Then there was the grudging, earth-protesting crash. We paced the Eucalyptus garden of the villa trying hard to be nonchalant. Hicks kept flinging himself into a small fountain enclosure, covering his head with his hands. We looked at his his long, thin body, so clear in the moonlight, and shivering, and we felt pity and shame. Tracer bullets form our own machine guns in the harbor etched their gleaming trajectory into the night.

When the morning came, Smith[6] and Allen[7], who had spent the night in one of the small hotels in town, returned. They had gone to town looking for women and booze, but had been forced to stay in a crowded refugio [bomb shelter] on

the hotel grounds. They told us that some buildings near the port had been destroyed, and two English ships damaged. There were also some casualties.

But then later in the morning, the order came to stand by. Nobody was to leave the grounds. Rumors circulated:

“We were going by boat to Catalonia – we were going by rail – the fascists had cut through to the sea.”

Bernstien[8], a hospital orderly, who had been too old for active duty, kept assuring himself and us:

“We’re going to the front where they need us; we came to Spain to fight, didn’t we? If we must die, we must.”

Nobody answered him.

Martinelli kept wandering around the grounds looking for a butt. All of us were ravenous for a smoke. We tried crushing dried rose leaves and rolling them. One puff was enough. Kelly kept repeating:

“What I wouldn’t do for a dirty old hamburger and a beer?”

For two days we waited. Then those of us who could, marched in a ragged line to the station in town where we were to board the train for the trip north. The train consisted of some ancient passenger cars without windows, and some freight cars which had been fitted out for the seriously wounded. It was a tedious wait in the station. We began to sing the first song we had learned in Spain:

Waiting, waiting, waiting,

Always f–ing well waiting,

Waiting in the morning, and

Waiting in the ni-i-ight;

God send the day when

We’ll f—ing well wait no more.

The tune was from the old hymn, “Onward Christian Soldiers.”

Some townspeople had come to say farewell, and among them was the town whore. In her loose-fitting kimono she even looked alluring. The people laughed to see her waving, and to see us waving and yelling back at her. Then, before the train pulled out, thin refugee children dressed in white, and – accompanied by nurses to the station platform bade us farewell. They came from the Swedish home in Denia. They sang, first the International, and then the Spanish anthem, Himno De Riego. It was deeply moving, and we yelled and waved at the children.

BY TRAIN TO BARCELONA

There was plenty of cognac on the train, and we had received a ration of bread and canned marmalade. Singing in half a dozen languages resounded in the rattling wooden cars as the train moved out. Some of the guys stood on the platform, anxiously eyeing the sky. Hicks was there, automatically scratching his lice.

We came to Valencia at night. The high glass-domed station was deserted and dark. The sirens had just sounded, and beams of light criss-crossed the sky. It was a false alarm. We had to wait in the station for many hours for another hospital train to which we were joined. This train had large, red crosses painted on the roofs of the cars. It also was fitted out with real hospital beds, and some of our seriously wounded were transferred to one of these cars. Two men who had disappeared some days ago from Denia boarded the train. We speculated that they had been trying to get to Catalonia on their own. Nobody questioned them.

Finally we resumed our journey in the cold drafty cars, chugging slowly northward along the coast. There was no more singing. We passed Castellon de La Plana at dawn, and a little later, when it was light, we stopped at a little town. Many people were grouped around an air-raid shelter near the station. Some yards ahead, men were busy repairing the tracks. A string of wreckage, splintered wood and steel – was piled in the ditch. Dried blood was still recognizable on the wreckage. Terrified peasant women told us, that a few hours ago, in the light of the moon, the train, full of young recruits, had been bombed. Many boys had been killed.

We spoke of the boys we had seen in the last few days, who were either sixteen to eighteen with hardly a hair on their faces – all singing and laughing, and carrying cardboard suitcases with clothing and bits of roasted chicken or rabbit their mothers had packed for them. The war was a lark to them, and we had felt sorry for them, recalling our first trip to the front and afterwards.

The train was delayed in the town for most of the day. Those of us who could went tramping through the narrow streets looking for grub. The shops were bare. There was a small tobacco shop that was loaded down with cigarette paper – but no cigarettes or tobacco. The woman who ran the shop asked if we had soap. Martinelli and I traded a couple of bars of soap for some eggs. The woman fried the eggs for us and added some potatoes, onions and green pepper, and fried it all in olive oil. It was the best meal we had eaten in Spain for many months.

There was a café which had some vile cognac and anise. Some of the fellows became drunk. Kelly and Brown[9] got into a fight. We had to pull them apart. We drifted back to the train and began singing “waiting, waiting, waiting,” but nobody really felt like singing. Somebody growled:

“You guys couldn’t even carry a tune in a pail.”

“Will we make it, will we make it?” was in everybody’s mind. “How close are the fascists to the sea?”

“It’s a hell of a war, but better than no war at all,” muttered Call-A-Meeting Joe.

We smiled wanly, having heard that old gag a thousand times.

“The next war I fight will be in Milwaukee, where a guy can get himself a mug of foaming Schlitz,” volunteered Spike, a middle-western veteran of the 1920 beer wars.[10] He had also been a steeplejack, and a worker in carnivals and circuses. We loved to listen to his stories. The story was told about Spike, that while in Teruel, and being detailed to grenade an enemy machine-gun nest, Spike, before throwing in the grenade had shouted:

“How many of you are there?”

“Five,” was the answer.

“OK then, divvy this up among yourselves,” and then let go with the grenade.

Spike of course, spoke no Spanish at all, but everybody was glad to believe it since he was so well liked.

The train pulled out when it became dark, and there was a full moon shining over the Mediterranean. Friendly bets were being made as to whether or not we would make it. We were served a meal of chickpeas, and lentils, and a cupful of wine. Hicks kept watch on the platform, frowning and looking anxiously at the sea and sky. We were passing through an olive grove when we heard the first, far sound of the motor. Conversations suddenly stopped. My mouth became dry. Then the motor sounded louder and louder, and I heard the first sharp cracks of the machine guns and the splintering of wood as the bullets hit the cars.

Then the train stopped, and from every side of the cars, men scrambled down into the ditches alongside the tracks. The Caproni was strafing and seemed to be pitching flashes of flame at the train. Bernstein, the orderly, remained standing next to the platform. We yelled at him:

“Get down, get down,” but he stood as if paralyzed, his mouth open as if he was trying to say something. Then the bombs came and there was no whistling as the plane was low. It was like a half-dozen small earthquakes, and the smoke made it difficult to see. Walters could be heard moaning:

“Help me somebody, or I’ll bleed to death – Oh my god, help me.” We couldn’t see him and there was nobody to help.

As the plane circled, the men raced for the shelter of the terraces and olive trees. Again the strafing, the bombs, the smoke, and shrapnel whistling through the air. We hugged the sandy earth, covering our heads with our hands. Smith, an Australian, was lying alongside me. He was trembling and his teeth were chattering.

“Will we ever get out of this bloody war? Will it ever end?” he kept repeating.

It was good to feel his body next to mine, although I felt his trembling communicating itself to me. Two or three more times the plan circled and came back, spraying the olive grove with its machine guns, knowing that we were huddled there, and then it flew serenely eastward over the Mediterranean.

We went back to the train, and through the haze of smoke that was lifting, the locomotive could be seen throwing off sparks from its stack, and puffing. Bernstein was lying in a pool of blood alongside the train, face downwards, and with his arms outstretched. Walters, still moaning had been hit in the shoulder by a bullet. Kelly was applying first aid to his wound and yelling for the doctor, who was busy with other wounded. The two cars that had contained the more seriously wounded, had been hit the worst. Many of the men had been hit again, and some of them died. During the night we removed the dead and wounded from the cars and placed them on the ground. Dr. Hart, the Austrian, his uniform splattered with blood, directed the work.

Some ambulances arrived at dawn to remove the wounded and dead, and they were driven south. The Polish woman doctor had been shot through the neck. She had been placed under an olive tree where she died. She looked strangely peaceful with the gray pallor of death upon her face. Near her, was her opened valise, with underwear, silk stockings, notebooks, and incongruously, a small pearl-handled revolver.

Later in the morning we heard the rumble of artillery not too far away. Dr. Hart had left in one of the ambulances, and there was nobody in charge. Spike and some of the guys decided to head north along the highway. They came back in a little while. They had met some Republican soldiers who told them the road was no longer open. Spike matter-of-factly announced:

“We’re stuck boys – The fascists are in Vinaroz – They’ve cut through to the sea.”

[1] Unidentified volunteer.

[2] Unidentified volunteer.

[3] Unidentified volunteer.

[4] Joseph Kelly (Irish-Canadian) b. March 10, 1898, Donegal, Ireland; Emigrated to Canada; Canadian Citizen; Single; Lumber Worker and Trade Union Organizer; IWW, IRA, CPC 1932; Domicile Vancouver, British Columbia; Arrived in Spain February 14, 1937;WIA Brunete; Returned to Canada February 2, 1939; d. January 2, 1977, Kamloops, British Columbia [Petro Data Base; & McLoughlin, Fighting for Republican Spain, p.199].

[5] Leon Blum was the leader of France’s Popular Front coalition government.

[6] Smith is an unidentified Australian volunteer.

[7] Possibly Robert Francis Allen.

[8] Unidentified volunteer.

[9] Unidentified volunteer.

[10] Nick Tosches, who completed extensive research on William Gresham while writing the introduction for the 2010 reprint of the Gresham novel Nightmare Alley, makes the case that “Spike” is most likely Joseph “Doc” Halliday. Tosches plans on publishing an extended work on Gresham. Email from Tosches to Brooks, March 4, 2015; The 1920 Beer War was a gangland turf war in Chicago during Prohibition.