Blast from the Past: A Letter to Bob Reed

Editor’s note: At the initiative of ALBA board member Chris Brooks, who maintains the online biographical database of US volunteers in Spain, the ALBA blog will be regularly posting interesting articles from historical issues of The Volunteer, annotated by Chris.Over the next three months, Blast from the Past postings will showcase articles about the American volunteers who served in the Artillery. Many of these articles ran in The Volunteer during Ben Iceland’s tenure as editor. Iceland, who served in the Artillery, recruited several of his fellow artillerymen to document their experiences. Iceland also shared his own experiences in a series of articles he originally wrote in the early 1940s. Together these articles shine a light on some lesser known American volunteers.

A Letter to Bob Reed

“El Duke” [Harry Hubbard]

[Originally published in The Volunteer, Volume 10, Number 2, August 1988]

First of all, thank you for your letter and your understanding of my feelings.

For some time I have shut out the reality of my participation in the Spanish Civil War from my consciousness; feeling that I had no honest part in it. I sought adventure, not knowing the difference between a Democrat and Republican, but who does know the difference? I grew to feel apart from the idealistic motives of most of the International, my observation being that whichever party (in Earth’s history) was in power, their power was maintained through harsh measures, not through brotherly love.

In April of 1937, I worked in a shipyard in San Francisco and the siege of the Alcazar was being played up by the media. Five young fellows, myself included, fantasized about joining the struggle, not even aware of which side was which. When a way was found to join (through the old Seaman’s Union of the Pacific), four of the five suddenly had sick mothers who couldn’t be left alone. My mother had long since passed on, so I had no excuse.

Greyhound bus to New York, in company of four Spaniards returning to their homeland. (I felt that this was assurance that I wasn’t just after a free ride to the big city.) Contact the next morning and since I had my US passport I was separated from the Spaniards and joined a fist-waving group of anti-fascist, waiting to board the British liner The Georgic. Arrived in Le Havre, France, heard speeches by Earl Browder and Bob Ford in Paris, then on to a small town next to the border, where for one night I was truly enthralled by revolutionary songs sung by anti-fascists from all over Europe (about 100 or more in the group). A 26-mile nighttime walk in rope sandals, over the mountains and into Spain in the first light of morning (April 1937).

I spent that first day resting in the stables of a fort. Then there was the exhausting train ride to Albacete, where we were issued ski pants, boots, and everything but firearms. Everyone we saw in Albacete seemed to carry a side-arm of every imaginable type.

All of the Americans with me were sent to Tarazona for two weeks of training, but I was held in Albacete to be assigned to the Air Corp, as a machine gunner.

After about a week of frustrated waiting while more arrivals came and departed for training, I was finally told that no planes were available and that I was to be assigned to the 1st Regiment of Train, in the south of Spain. (I had had maybe 30 minutes on a machine gun in the National Guard in Utah, but had given that as my qualification when interviewed in San Francisco).

I joined other Americans and some Englishmen, as well as a small mixture of Europeans in the small and very beautiful town of Almansa, where we were to wait for our artillery pieces. Except for some of the tales of action on the first morning of the Revolution, as told by the townspeople, the war was far from us. A fair amount of food was available, and the beverages and women… delightful!

Much of our time, outside of guard duty, was spent, almost daily, listening to political speeches, supposed to keep up our morale, which was in a good but somewhat bored shape. When our guns did arrive, we were faced with ancient 155mm howitzers that had been sold to the Czar of Russia by France. They were equipped with huge tail skids, and wooden tractor treads on the wheels and ramps, which they were supposed to roll back onto on the recoil. The cinnamon-like sticks of powder had to be re-enforced again by half to bring our trajectory to 6 or 8 kilometers, so we were near our trenches and answering behind us, most of the time. They were equipped with French gomimiters and Russian B.C. scopes, or vice-versa. With the training and formulas, worked out in Russia during our officers’ three-month stay there, the guns proved fairly accurate.

Timpson [1], our C.O., was quite a man, and I remember sitting chatting with him while he removed the setting heads from the shrapnel shells, scraped the rims to insure better contact, and reset them. One spark and goodbye, but by then the fatalistic attitude had taken over: can’t live through it, or can’t be killed anyway, so why worry.

In spite of all this, I have a deep love for the Spanish people. It may not be reality to you, but I attribute it to “past lifetimes” spent there or under her cultures. Anyway, we spent most of our time overlooking Toledo. There were three artillery batteries: our American (with some English and Europeans among us), one French, and one English battery.

When Spain was cut in half, we were still there, until the International Commission arrived in the North of Spain to retire those surviving volunteers in a pseudo-effort to lift the embargo. We waited in different towns after being removed from the front, ending up finally in Valencia, always under the 5th column threat and occasional searching aircraft. Valencia was safer after we were quartered in the stables, where the famed white show horses were trained.

In the resulting boredom, four or five of us went AWOL whenever we heard of a little town as yet untouched by the war, and would return after an enjoyable visit. (Even when out of funds, there were always Spanish soldiers in the bars, willing and eager to pay the tab for the Internationals.) Needless to say, we had considerable guard house time accrued, but not strictly enforced, as all thoughts were on going home. Finally after the Northern Volunteers were out, the International Commission did arrive in Valencia and would sit on the balcony of the Hotel Metropol, opposite the Bull Ring and watch the daily bombing, mostly by the Italians. They would probably be there yet, except that some bombs were accidentally dropped nearby and they were motivated into action, and they checked us out.

Then more waiting. The boats sent to evacuate us helped make Valencia harbor look like a great pin cushion, as they ended up on the bottom of the harbor from the morning bombings. Then about the time that Franco was nearing Barcelona, we boarded a small freighter flying the French flag (I think about 300 of us), and departed at midnight, cruising about one mile off shore. Opposite Taragona an Italian heavy cruiser or battlewagon opened fire on the town, producing unbelievable frustration as the shells passed overhead. In the morning light, as we approached Barcelona harbor, one of our subs surfaced. A short, emotional stay in Barcelona, then in a small town to the north, where we were issued a suit or an overcoat, then more waiting.

On the day that Franco entered Barcelona, a train was due to take us across the border, but with the 5th column so active, our officers stopped an earlier train, evacuating the civilians, and we boarded it. The following train, the one that we were to be on, was bombed off the tracks, with heavy casualties. We were then across the bridge, through the tunnel, and into France (Feb. 1939).

As to problems encountered in the US Army, yes there were some. Also, as a photographer with the Bureau of Reclamation and later the Army Corps of Engineers, some harassment, first by the FBI and later the CIA.

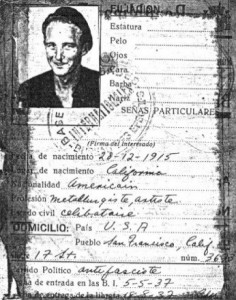

I am enclosing my military book and a few photos. Do whatever you choose with them, or if they are of no value you may destroy them. I have had them long enough. The ID photo is not the original, a barmaid in Valencia has it, or did have.

As a footnote, if interested, I have been, off and on for the last 40 years, in or on the fringes of what is called the New Age Light Groups, and have found, to some degree, the realities of what I seek. I am also an ordained minister.

Wishing you all and all sincere seekers in whatever they believe … the very best.

Sincerely,

“El Duke”

[1] Arthur Timpson’s previously published piece details his crossing of the Pyrenees and subsequent imprisonment in the fort at Figueras.