Blast from the Past: Deyo and John Jacobs

Edward Dayo Jacobs, Photographs VALB/ALBA; Artists’ Union Rally, l. to r. Edward ‘Deyo’ Jacobs, Winifred Milius, and Hugh Miller, ca. 1935 / Irving Marantz, photographer. Gerald Monroe research material on WPA, American Artists’ Congress, and Artists’ Union, [ca. 1930-1971]. Archives of American Art.

Deyo Jacobs – March 1938; A Delayed Obit

Art Landis

[Originally published in The Volunteer, Volume 2, Number 3, 1979.]

It is said that Pablo Picasso once looked at a faded newsprint aerial-pic—and painted Guernica!

The one book which most Lincoln vets brought home from Spain was The Book of the 15th Brigade. Though the English edition, as edited by the much loved Frank Ryan, was admirable, it still, however, had one flaw. The submissions of Deyo Jacobs, a young Jewish artist from New York, and a veteran of Jarama, were overlooked.

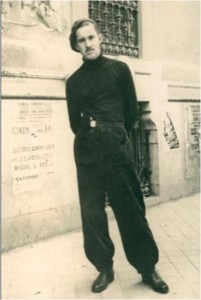

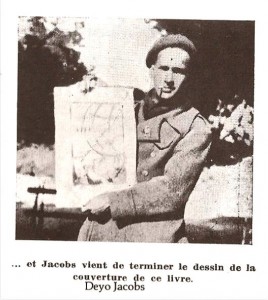

The French made no such error. Their editor, the respected 15th Brigade Commissar, Jean Barthel, seized them instantly for his own. Thus while the English edition has no artwork at all, the pages of ‘Le Livre de la 15eme Brigade’ display with pride a photo of Deyo himself, and the paintings and sketches that so reflected his own humanity and his deep understanding of the Spanish struggle. Deyo is shown (see pic), cigarette dangling and beret at a cocky angle, as a bonafide, rive gauche poilu;[1] this, while he holds the cover he designed and which was finally used for the Book of the 15th Brigade —in all its editions.

I remember Deyo well. Attached to the HQ Co., Mac-Pap battalion staff, he and I, with Doug Taylor, Al Cohen, John Miltenberger and Clyde Taylor, were Observers, Mappers, Billeting mostly with the snipers, we became quite close as combat cadres usually do. Our gab sessions became everything; at the Tarazona base; in the aftermath of the melee of blasted tanks and wasted lives at Fuentes; during the autumnal days of rest—the fighting at Argente; Celades; and the frozen inferno of Teruel…

I was forever fascinated by the stories of Deyo, Doug and Clyde Taylor (the latter from Antioch; not related); especially the wild tales of O’Henry’s New York, and particularly the “Village” … They seemed to me as left-socialists of a sort, drawn to Spain like most Lincoln men, by the strength of their own convictions. Indeed, theirs were more a reflection of the straight-form-the-shoulder honesty of Debs and Jack London; of that grass-roots golden age of American socialist-populism, and of Big Bill Haywood and his 250,000 member wholly American, I.W.W…. My background was California. Steinbeck country. Riding freights at fifteen. Picking fruit. Panning gold along the Kern.

As a nineteen-year-old, gung-ho YCL type with a penchant for things military, I was also, as Deyo put it, a “contradiction.” For I possessed “a sense of the ridiculous” which he swore would, in the long run, preserve my free-thinking spirit and assure me the eventual humility that all those who propose to speak for others must somehow achieve.

Indeed, on the strength of this analysis, it was Deyo who campaigned for me to become the only elected headquarters Company commissar the Mac-Paps ever had. Our promise: To keep bullshit to a minimum, stay the hell out of the way, and above all to see to it that newspapers and mail arrived on time, plus cigarettes; and that would get our share—no more, no less—of whatever goodies the Intendencia had to offer.

Indeed, on the strength of this analysis, it was Deyo who campaigned for me to become the only elected headquarters Company commissar the Mac-Paps ever had. Our promise: To keep bullshit to a minimum, stay the hell out of the way, and above all to see to it that newspapers and mail arrived on time, plus cigarettes; and that would get our share—no more, no less—of whatever goodies the Intendencia had to offer.

Deyo was not mechanically inclined. A rifle bolt, or the lock of a Maxim, was to him but an uninteresting jig-saw puzzle. He had little patience with such; not that he couldn’t fire them. He could—and did! His maps, however, were fantastic; his panoramic sketches, beautiful.

He was also uncoordinated, so that for him any march would quickly become a thing of pain and agony. We’d carry his gear, his pack and his rifle; do what we could … Stories of Deyo are myriad. Example: The Tarazona scandal, wherein he and Doug and Clyde, much too practical to look for nonexistent paint thinner while making posters, used urine instead. The result, a beautiful but oddly colored job. Commissar J. Dallet was furious. The Mac-Paps laughed all the way to Aragon. At Teruel I took him, at his own request on a night patrol, to skirt the fascist wire. (I’d also been given the nebulous title of “chief of scouts,” except there weren’t any, only men and whoever I could whistle up.) Needless to say, with Deyo by my side it was like doing the job in broad daylight; the less said, the better. A measure, too, of Deyo’s intensity was that in conversation you’d quite often find him standing on your feet while he made his pint—eyeball to eyeball!

How, indeed, could one not love him?

The peaceful, Christmas day of ’37 were spent in Mas de las Matas, awaiting the call to Teruel. I still have the list of donated pesetas and donors for a toy and candy fund for the village children. Deyo helped collect it. On the final day, save one, we both jawboned the last bottle of cognac from the Intendencia to celebrate the birth of a son to Jack Penrod, one of the snipers. A letter from his wife had just arrived.

Toward the end of the cauldron of Teruel, the Mac-Paps, depleted, worn out by the deep snows and bitter fighting, still held their “post of honor” before the city. In the final days of the great fascist counter-offensive, Deyo and I were sent to a post to the front and west of our 3rd Co. Shells from enemy guns – over a hundred and fifty lined up hub-to-hub before Concud—ranged all our positions. Within minutes our phone was useless. We saw then, through the great clouds of cordite, dirt and chalk dust, such a panorama of war as is seldom given for men to witness and survive. To the east was our own 3rd Co. Beyond them three hills held by Spanish Marineros.[2] Much further along was the escarpment of El Muleton, held by the Thaaelmanns[3]… And over all the plain above the valley of the Turia and the Alfambra were the advancing brigades of Franco’s Corps of Galicia. Through the long hours of the morning we watched as the Thaelmanns were destroyed; likewise the Marineros. Our 3rd Co. then retook one of the hills—and the British came down the face of the cliff of Santa Barbara to form a last thin line of bayonets across the valley’s mouth at the 3rd Co.’s right flank.

It was like some monstrous, living mural. All the afternoon they came on in waves and columns, banners flying, driven by their officers. They died before the heavily reinforced 3rd Co. front and the British line. And then they ran – and came on again; and were slaughtered again, and yet again… Cut off as we were, we never expected to survive, Deyo and I. Still we kept up a steady fire into the flank of those hitting our 3rd Co. front. Time passed, and at one point I turned to see Deyo, covered as I was with dirt and chalk-dust. His map case had replaced his rifle. He was sketching what he saw, methodically, deliberately: “While there’s still some light,” as he put it. The shelling, of course, had never ceased, nor the searching bullets from enemy machineguns.

It was like some monstrous, living mural. All the afternoon they came on in waves and columns, banners flying, driven by their officers. They died before the heavily reinforced 3rd Co. front and the British line. And then they ran – and came on again; and were slaughtered again, and yet again… Cut off as we were, we never expected to survive, Deyo and I. Still we kept up a steady fire into the flank of those hitting our 3rd Co. front. Time passed, and at one point I turned to see Deyo, covered as I was with dirt and chalk-dust. His map case had replaced his rifle. He was sketching what he saw, methodically, deliberately: “While there’s still some light,” as he put it. The shelling, of course, had never ceased, nor the searching bullets from enemy machineguns.

Dusk came finally. We had held and they had lost. And Deyo and I, in shock and a little high on it all, made it  back to the railroad cut, and then to Battalion HQ.

back to the railroad cut, and then to Battalion HQ.

On the following day I was sent by Major Smith as liaison to the new British positions. The enemy action was repeated, and still we held. I was hit, however, in the early hours. I never saw Deyo Jacobs again, nor did I return to the battalion.

Almost a year later at Ripoll, awaiting the train to take us to France, I saw Jack Penrod. He told me that in the retreats he had found Deyo and Doug Taylor beneath a tree somewhere south of Hijar; that Deyo; in bad shape, could no longer walk at all. Doug had decided to stay with him. At that very moment fascist tanks were on all the roads; enemy cavalry swarmed over all the hills and valleys. No one saw them alive again and it is presumed that like so many tens of others, they were taken finally, and summarily executed.

These few paragraphs, plus the accompanying artwork falls far short of being the story of Deyo Jacobs. His background data, the milieu from which he came, is missing. Still one can conclude a point: To read of the uniqueness and humanity of Deyo is to also touch upon and recognize, perhaps, the full measure of our loss in those sixteen hundred Lincoln dead for whom there was no obits; and who, indeed, are but names today; forgotten, except by the few who knew them.

Deyo Jacobs – A Reply

[The Volunteer, Volume 2, Number 4 (cover incorrectly indicates 2), 1979.]

Dear Mr. Landis,

About the most moving thing that has ever happened to me was to received your beautiful piece, “Deyo Jacobs – March 1938; A Delayed Obit.” I had been in correspondence with Carl Geiser of Smithtown, New York, and he very kindly forwarded it to me.

Deyo Jacobs was my brother and this was the first time our family had any clear intimation of how he died. The great pity is that our parents never knew. Just recently I made copies of Deyo’s letters from Spain and my parent’s desperate attempts to find out what had happened to him. It was a nightmare time for all of us. At the end of your piece you observe that his background, the milieu from which he came is missing. Perhaps I can supply some of that.

His full name was Edward Deyo Jacobs and we called him “Eddie.” He grew up on a farm near New Paltz, New York, where his mother’s family (the Deyo family) settled somewhat prior to 1690. His father came from further upstate, Delhi, New York, where his father was a lawyer and Congressman and had fought long and hard in the Civil War as a cavalry officer, ending up as a brigadier general. As a boy, Eddie was as intense as you suggest and was really at war – sort of a holy war – with the conservative, rural community where he grew up.

He drew from an early age. You mention his maps. One of the first things he drew were marvelous maps of lost treasure islands which were aged by crumpling coats of shellac. Like his parents he was a thoroughgoing romantic. His parents supported him both in his art and his political commitments.

The great transformation came when he went to New York and discovered that there were other people pretty much like him. He went to the Art Students League, studied with Benton and George Grosz, and discovered radical politics. As you observe he was very much in the tradition of John Reed and populist radicalism.

Recently, while reading his letters from this period and from Spain, my sister and I wept to realize how little we had known him. He seemed so wise and loving in his letters, whereas we, being 3 and 5 years younger than he, were both somewhat frightened by his tempestuous feelings and sorely pained by his conflicts and suffering.

It has seemed to me that this period, say 1936 to the outbreak of World War II, was crucial to the character and development of America and I would like to do an exhibition (exhibitions are my business at the moment) that would use my brother as a focal point. It would be a biography in terms of the time and experience he lived through. I have a great many of his drawings and paintings and they are very powerful stuff, if sometimes not fully realized.

I don’t have any clear idea yet of exactly what the scenario for this exhibition would be – how much would be personal and how much the larger scene. But I do have – or think I have – an idea of what it would mean to an audience who is largely unaware of what the war in Spain meant.

Perhaps the point is that truth without passion or commitment is a socially and politically meaningless.

At one point in his letters, Eddie questions whether being a revolutionary artist, rather than a revolutionary activist bearing the brunt of the battle, is not some sort of cop out. He says that being a revolutionary artist is like having a wet dream – an orgasm without physical contact. (His phraseology is better but that’s the idea.)

In any case, although I have limited time and energy beyond my job at this time, I hope to start doing some thinking and research about this exhibit idea. I want to do it for personal reasons, but I also think it would make a timely and useful statement for this time.

However that may be, this is written to express my profound gratitude and indebtedness to you for your lovely evocation of the brother I loved and suffered with and my admiration for your ability to evoke a time and an experience in a manner quite worthy, in my admittedly subjective view, of Leo Tolstoy.

Just beautiful. Thank you.

John Jacobs

[1] Literal translation is an “awkward hairy Soldier” but Landis uses it as a compliment implying that Deyo exhibited a sense of bohemianism and creativity.

[2] Spanish Naval Infantry.

[3] XI IB, as well as one of its battalion’s was known as the Thaelmann.