Escape from death row: Three Lincoln POWs on trial

At their arrival to New York on the 17th of March 1940. From left to right: Clarence Blair, Rudolph Opara, Lawrence Fant Doran, Anthony Kerhlicker and Harry Kleiman (Cohn Haber). (AP Wirephoto)

In February 1940, one year after the end of the Spanish Civil War, eight members of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion still languished in Spanish prisons, subject to judicial military proceedings by the Francoist army. Among them were Peter Kerhlicker, Rudolph Opara, and Larry Doran. Buried in the Spanish military archives are documents of their trials. The Volunteer presents an original investigation.

(Version in Spanish with references.) On March 9, 1938, Franco’s Army launched an offensive, devastating Republican defenses in the Aragon area. U.S. Brigaders of the Lincoln-Washington Battalion began a retreat through Aragón that would last until March 18, when they were sent to the Republican rearguard in Catalonia to be reorganized and rearmed.

Anthony Peter Kerhlicker, Rudolph Ludwig Opara and Lawrence Fant Doran were members of the American Battalion. Larry Doran, 25, was the “rookie.” Born in Los Angeles, he had entered Spain on March 6, just before the retreats began. He did not join the Battalion until March 30. He was the only one of the group who was married. Kerhlicker, 31, was born in Polk County, Iowa but lived in Moline, Illinois. He came to Spain in June 1937 and held the rank of Sergeant in a Fortification Group. Opara, 21, born in Cleveland, Ohio, had been in Spain since mid-August 1937.

On March 30, 1938, advancing Nationalist troops crossed the river Matarranya. The Fifteenth Brigade was sent to defend the line on the next river on the route, the Algars, covering the area between the villages of Nonaspe and Batea. There they were attacked by units of the 55th Division of Franco’s Army and withdrew on the evening of April 1 towards the town of Gandesa, arriving in the morning of the following day. There they would be cornered by the First Navarrese Division that had surrounded them. The night of April 2-3, the American Battalion ceased to exist as such, breaking into small, isolated groups of Brigaders fleeing to avoid capture. It is at this moment that the odyssey of Kerhlicker, Opara, and Doran begins.

If we can trust statements that were taken after they were detained, the three men were fleeing separately, hiding and finding food in country houses and farms. Kerhlicker and Opara met on April 10. Doran joined them not much later. We do not know the exact route they followed, but they traveled through mountains and fields along the river Ebro, without daring to cross it, going towards the Mediterranean. In his book Prisoners of the Good Fight, Carl Geiser reports that the three were captured on April 19. That is inaccurate, since in the documents of the Summary Trial it is clear that their detention happened on April 27. This means they had been on the run for 24 days, crossing 90 kilometers (60 miles) of unknown territory from Gandesa to Sant Carles de la Ràpita, where they were caught.

Sant Carles de la Ràpita had been occupied by Franco’s Army on April 19. The buildings of its Town Hall housed the Military Command of the Second Regiment of Black Arrows, an Italian Unit of the CTV (Corpo Truppe Volontarie). It was there that the 19-year-old Domingo Vizcarro Sanz, who lived in Sant Carles, went at noon on April 27 to denounce the presence of three “militiamen, apparently reds” in an estate close to the urban area. In his statement taken two days later, he and his companion, Tomás Subirats Aguilá, 18, were traveling in a cart to the estate of the Tomás’ father, called Torre del Moro, with groves of olive trees and carob-trees and a view of the bay a kilometer away. Before arriving at the estate’s main building, they met a man who, with signs and some Spanish words, was asking for food. They advised him to go into town, but he replied that he would not do so because the town was Fascist. The boys invited him to get in the cart, promising they would get him something to eat. After jumping in, the stranger called two other men who were hidden in the bushes, who came to the cart. The Brigaders saw the emblem of the Falange on the cart and said that they would rather die than be Fascists. They showed a hand grenade. They also asked if Tarragona was already occupied.

Old photograph of the house of la Torre del Moro where the three Lincolns were captured: A magnificent building with a fortified tower from the 16th century which was part of an old defensive line of watchtowers of the coast. (Photo courtesy of Paco Carles. Sant Carles de la Ràpita)

The boys took the three trusting Americans to the house of Torre del Moro and left them to prepare something to eat, while Domingo Vizcarro ran to denounce them to the military authorities, and Tomás watched from a distance. The patrol sent to capture them was composed of an Italian Sergeant, Michele Frappampina, a Spanish corporal and two Spanish soldiers. In the statement taken from the Italian four days later, he stated that one of the Brigaders had made gesture of throwing a hand-grenade as soon as he saw the patrol arriving, but eventually submitted without resistance.

Although the three were captured on April 27, their statements were not taken until six days later in front of the Examining Magistrate, Captain Jesús Dapena Mosquera, along with the Secretary, Second Lieutenant Antonio Martínez Aduriz, and the warrant officer Jose María Comalrena de Sobregrau Egozcué serving as translator. Kerhlicker was questioned on May 3, the other two the following day. All three stated that, being unemployed, they had come to Spain to work and had joined the International Brigades against their will. Kerhlicker claimed that he came to work as painter in hospitals; Opara that an organization in Cleveland told him that they would provide him with a machinist’s job in Spain; and Doran that an agency called “All Nations Employment Agency” promised him metallurgical work in Spanish industry. They lied, feeling they could not admit that they had volunteered to fight against the army of which they were now prisoners.

The three also declared that they had never used a rifle. Kerhlicker claimed in his discharge to have been assigned to a Section of Fortifications; Opara to Ammunitions; and Doran to have received instruction as a First Aid man. Doran added that during the seven days since he had been arrested, he had received better treatment than during his entire time with the International Brigades. As Carl Geiser writes, however, “the Italians not only beat them but they did not feed them for the first four days, with the excuse that they were going to be shot anyway.” Matters got worse when the Italian Sergeant Frappampina made another statement. Correcting his first version, he now claimed that one of the Brigaders, Larry Doran, had two hand-grenades, one of which he had thrown. It had exploded without hurting anybody. The other grenade was taken from him immediately afterwards. In subsequent days, judicial authorities interrogated the soldiers of the patrol, who confirmed their Sergeant’s version. When it came time to question the two boys who had denounced the Brigaders, however, both denied having heard an explosion during the capture. On May 10 the Brigaders were questioned again; they denied that they possessed more than one hand-grenade, which they had handed over voluntarily. Contrasting the different testimonies, it seems clear that the Brigaders were being entrapped for trial.

Prison of Vinaròs located in the former convent of San Francisco, where the three Lincolns entered on May 13, 1938. (CDGCE Vinaròs)

The Summary Urgent Trial was scheduled for May 16 in the coastal town of Vinaròs (Castellón), situated 25 kilometers south of Sant Carles de la Ràpita. The three Brigaders had been escorted to there by the Guardia Civil on May 13. We can assume that this was a typical military trial or Court-martial, since the roles of President, Secretary, Members of the Court, Attorney and Defender were all taken by members of the military. Although they did not have any juridical formation, this did not represent any hindrance when it came to applying sentences. There was a translator present at all times. No statement of the defense appears in the proceedings.

The prosecutor asked for the death sentence, based on the alleged throwing of a hand-grenade. He underscored that the three Americans had stated “that they would die defending themselves rather than be Fascists” and that they had come to Spain to enlist voluntarily in the “Red Army.” He accused them of the crime of military rebellion. (As per articles 237 and 238 of the Code of Military Justice, rising up against the legitimate government was punishable with life in prison or death.) The Court sentenced the three Americans to life in prison, and the sentence was signed by all three Court members.

Yet this was not the end of the Court-martial. The same day, a member of the Court, Captain Jose Luis Escobar Buiza, filed a dissent to

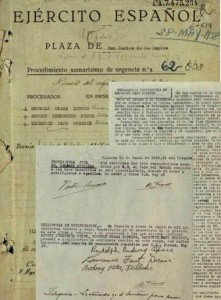

Original documents of the Summary Trial nº62/1938. The Lincolns’ names and signatures are visible. A.H.D.(Archivo Histórico de Defensa), CDGCE Fund Caixa Vinaròs

change the initial sentence. This 50-year-old Captain, born in Seville, had joined the Army in 1909, taken early retirement in 1931 (taking advantage of Manuel Azaña’s Law of April 25, 1931), and rejoined the Army at the beginning of the war on Franco’s side. Although Escobar had signed the initial sentence, in his dissent he accused the convicts of being dangerous and responsible of the incalculable “losses caused by the red revolution “in which they had participated “materially and voluntarily.” With these arguments he requested that the punishment be changed to a death sentence.

The prisoners knew nothing of these developments. Three days later, the Auditor, Ángel Manzaneque Feltrer, overturned the Court-martial because, as mentioned, the intervention of the defense counsel was missing. He ordered that the procedures be passed to the defense for a retrial. The new trial would be postponed until May 23 at 4pm. We don’t know to what extent the prisoners were aware of their procedural situation. Carl Geiser only mentions that both trials ended with a death sentence.

The retrial included two new faces: the Secretary and one of the Members of the Court were changed. The prosecutor again demanded the death penalty. The defense counsel asked for clemency, arguing that the three Americans had gone to Spain cheated “by the grand and well paid propaganda from the Red leaders.” He requested that the Court consider them “prisoners of war against their will.” During the retrial, the accused were questioned as well. Opara said nothing, Kerhlicker stated that in letters written to his friends he always told them that he was in a Section of Fortifications, and Doran said that he had never fired a shot at Franco’s soldiers.

This time the death sentence was definitive. The three were found guilty of being “authors by direct, material and voluntary participation” in the “military rebellion,” with “the aggravating circumstances of social dangerousness of the delinquents.” The following day, the Auditor confirmed the sentence. All that was needed for it to be carried out was the obligatory, final “Agreed” from Franco’s Headquarters in Burgos.

The response from Burgos did not come until three weeks later. The three Brigaders were told that Franco “had deigned to commute” their death sentence to a 30-year prison term. In other words, the Americans would be in jail until April 27 1968. (The sentence was the same for the all three. Contrary to what Cecil Eby insinuates in his two books, Larry Fant Doran’s case did not receive special scrutiny due to the fact that he shared his last name with Commissar Dave Doran, who had gone missing in the Retreats. Eby’s theory that the Nationalist authorities suspected Larry and Dave were the same person is unfounded, given that all the documents refer to Larry, mistakenly, as Laurence Fant Dorance.)

The Central Prison of Burgos, inaugurated in 1932, is very close to the city of Burgos. (CDGCE Vinaròs)

From this moment the three men shared the same fate. Although Geiser hints that Opara could have passed through another prison, the three Americans were taken together to the Central Prison of Saragossa on July 3, and then on September 5 to the Central Prison of Burgos to serve out their sentences.

There was some hope left, however. Throughout the war, international POWs, which included Italians and Germans fighting on Franco’s side had been freed through prisoner exchanges. The first liberation of U.S. volunteers took place on October 8, 1938, when 14 Brigaders were exchanged for 14 Italian prisoners in Irún. The U.S. ambassador in Spain, Claude G. Bowers, carried out the negotiations. The next liberation of Americans occurred on April 22, 1939, also in Irún, with the exchange of 71 Lincoln Brigaders. From Irún, the freed Americans went to Le Havre and then set sail for New York, with tickets paid for by the Friends of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (FALB). Negotiations were again initiated by Bowers. When the war ended, Bowers resigned and H. Freeman Matthews (Chargé d’affairs) finalized the exchange. But not all American Brigaders had been released. Eleven prisoners were still held in the concentration camp at San Pedro de Cardeña, and eight more in other jails, among them Kerhlicker, Opara and Doran. These eight were subjected to penal procedures, that is to say, they all had been judged and condemned for committing crimes.

The end of the Civil War also meant the end of prisoner exchanges. From then on, the release of remaining Americans became a diplomatic matter between the United States and Spain. (A recent book by Joan Maria Thomàs, Roosevelt and Franco during the Second World War: From the Spanish Civil War to Pearl Harbor, describes this process.) The new U.S. Ambassador Alexander W. Weddell did not arrive in Spain until May 1939. Before his departure he met with the Undersecretary of State, Sumner Welles, who charged him with several immediate tasks: a request of the new Spanish Government for a credit of cotton acquisition in the United States; an American entry request for Colonel Sosthenes Behn, the proprietor of the ITT (International Telephone & Telegraph Corporation) and also the majority owner of the CTNE (Compañía Telefónica Nacional de España) to be at the head of the company; and the demand for the release of American Brigaders still held prisoner. Weddell had little sympathy for the Brigaders. In an April 1940 letter to a friend, he described the volunteers as having been mistaken and badly informed.

On June 14 1939, the third Secretary of the American Embassy, visited the three prisoners and delivered a package with food and clothes. According to Geiser, Doran, who was in the infirmary, told the official that they were treated better in prison than they had been by the Italian soldiers who captured them. The Secretary reported that Doran was suffering from scabies, rheumatism and stomach trouble; Opara was pale and thin, had scabies and two boils. About Kerhlicker, he reported both good spirits and physical condition.

One week later, Ambassador Weddell met with the Spanish Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Count of Jordana, to deal with the issue of the 19 Brigaders who were awaiting liberation. Weddell argued that this matter was hindering the relationship between both countries and informed the Minister that the State Department was receiving many requests from relatives. He complained that the Auditor of War had not provided a list with the names of remaining American prisoners and the details of their charges. Jordana promised to solve the matter, but only for those Americans who were not involved in specific crimes. This excluded the three men.

On July 20, Counselor Robert M. Scotten from the U.S. Embassy met with Franco’s Undersecretary of Foreign Affairs, Domingo de las Bárcenas, who suggested that “if he can obtain the cotton credit, the Generalissimo not only will allow for Behn’s return, but also he will authorize the liberation of the prisoners.” After that, the three issues would remain linked. Two days after this interview the U.S. Secretary of State, Cordell Hull agreed to the concession of credit to buy 250,000 cotton bales. (The decision was not immediately made public.) On July 24, Weddell met with Franco, who assured him that the prisoners would be liberated, and then with the Count of Jordana, who ratified the release of an undetermined number of Brigaders. Still, he did not guarantee the liberation of those sentenced for specific charges. Two days later, the State Department contacted FALB with the news, urging them to collect funds to pay for the Americans’ return. The FALB organized a fundraising campaign, and the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade (VALB) contributed as well. Although the Roosevelt administration was helping with the repatriation, it refused to cover travel expenses.

On August 7 the concession of the credit for the acquisition of the cotton bales was announced publicly and 18 days later 11 imprisoned Brigaders at San Pedro de Cardeña were released. However, eight volunteers sentenced for specific crimes were still awaiting their repatriation: Anthony Kerhlicker, Rudolph Ludwig Opara and Larry Fant Doran, imprisoned in the Central Prison of Burgos; Alf Anderson and Reuben Barr (Conrad Henry Stowjewa) in the Central Prison of Saragossa; John Clarence Blair and Harry Kleiman (Cohn Haber) in the prison of Valdenoceda; and Harold E. Dahl, who was imprisoned in Salamanca.

On August 10, Colonel Juan Beigbeder was appointed as Franco’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. The U.S. Ambassador threatened that if the matter of the CTNE was not solved, no more credit would be granted to Spain. In November, Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles wrote to Weddell after a meeting with the Spanish Ambassador to the USA:

… it is hard to understand the delay of the Spanish Government in carrying out the promise which General Franco gave you personally to release the remaining American citizens who are still under detention as prisoners of war … Given what we have done for Spain in the way of credits, et cetera, it seems to me that the next move is definitely on the Spanish side. The release of these men, the trial of American citizens under detention of various charges not connected with hostile military service, and a prompt and equitable agreement with the American owners of the telephone company would seem the least we could expect.

Economic relations between both countries would be key for the liberation of the prisoners.

On December 12, 1939, the third Secretary of the American Embassy in Madrid visited the three men in Burgos, delivering holiday packages prepared by the Ambassador’s wife, with food, shoes, clothes, and cigarettes. At the beginning of January 1940, the matter of the CTNE was still not resolved. Shortly afterward, Franco’s Ambassador to the U.S. met with Undersecretary of State Welles to request a credit for the production of nickel coins. Welles admonished him severely for the rigid attitude of the Spanish Government. On February 3, the Spanish Ambassador sent a telegram to Franco’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, warning that the United States will not concede the requested credit until “we find a formula to please them.” Since the unresolved matter of the CTNE would not be sorted out until August, this formula would seal the release of the eight American prisoners.

At their arrival to New York on the 17th of March 1940. From left to right: Clarence Blair, Rudolph Opara, Lawrence Fant Doran, Anthony Kerhlicker and Harry Kleiman (Cohn Haber). (AP Wirephoto)

Documentation of the Summary Trial has no information about the three Americans from August 1938 until February 17, 1940, when a communication was sent from Burgos Central Prison to the Vinaròs Military Judge announcing that on that day, the three volunteers’ sentences had been commuted and they had been released. The three were escorted to Madrid. Wearing the clothes they received for Christmas, they were met by representatives of the American press who reported that they were “very, very happy.” On February 21, they spent one night at the Provincial Prison of Seville, where they met with Harold E. Dahl, John Clarence Blair, and Harry Kleiman, who had been moved from different prisons. The following night, the released volunteers were turned over to U.S. Consul John N. Hamlin and boarded the freighter Exiria bound for New York. Only six Brigaders were on the ship; Alf Anderson and Reuben Barr set sail later on the Exford. The passages were paid for with funds from the American associations of Brigaders.

The repatriation from Spain of six Americans hit the newspapers in the States because Harold E. Dahl was a famous aviator who had been captured in July 1937. The newspapers reported at the time that he escaped death thanks to his beautiful wife, Edith Rogers Dahl, a famous night club singer, who wrote a letter to Franco asking for clemency, and included with it a rather provocative photo of her. Supposedly Franco replied assuring her that her husband’s life would be spared. He signed the letter with the phrase “Your obedient servant kisses your foot.” On their arrival, Dahl was retained by the police due to a few checks that had bounced in 1936. Kerhlicker told to the press that during their trip on the Exiria it was the first time in two years that the three Brigaders ate meat.

Curiously, the documentation of the Summary Trial does not finish with the Brigaders’ exit from Spain. Once set in motion, the wheels of Franco’s bureaucracy kept turning, generating an absurd sequence of events. On March 4, 1943, three years after their liberation, the Provincial Commission of Examination of Sentences in Castellón de la Plana proposed the commutation of their sentences from 30 years to 6 years in prison, but the Central Commission refused the proposition and commuted them to 12 years. The ineptitude of Spanish justice had no limits: Two months later Castellón’s Military Judge requested from the Burgos prison the addresses of the Brigaders (who should be still in Spain, according to the Administration of Military Justice) to communicate to them their commutation. Incredible as it may seem, in February 1952, 12 years after the volunteers’ return to the United States, the Central Prison of Burgos replied to a letter from the Commanding Judge of the Military Court, informing him that in 1940 the three Americans had been expelled from the country. It was not until January 29, 1954, almost 14 years after their release that Spain finally closed the Summary Trail.

Anthony Peter Kerhlicker, Rudolph Ludwig Opara and Lawrence Fant Doran would die years later in the United States. They never knew all the details of their case.

For a longer Spanish version of this article with footnotes, click here.

Anna Martí Centellas was born in Terrassa (Catalonia, Spain) in 1970. She works in a national park and has long been fascinated with the English-speaking members of the International Brigades. Francisco Cabrera Castillo was born in Vinaixa (Catalonia, Spain) in 1951 and lives in Gandesa. A retired service member and researcher of the Spanish Civil war, he is the author of the book Del Ebro a Gandesa and co-author of El frente invisible, which deals with the history of the Republican guerrillas in the years 1936-39.

Well done Anna! a ‘by line’ for you and well deserved. A very interesting and fascinating story. Keep up the good work.

Dear Anna and Cabrera:

A marvelous piece of research and an enthralling story! So important to keep this history alive and you’ve done a marvelous job!

My very best wishes to you both.

Nancy Phillips FFALB

Very interesting and detailed information. Carry on with the excellent work in 2014.

My best wishes for Christmas and the new year.

Terry Bayes Int. National Brigade Memorial Trust U.K.

WHAT HAPPENED TO THESE MEN AFTER RELEASE? WHAT LIVES DID THEY HAVE?