Faces of ALBA: Evelyn Scaramella and Victor Grossman

In every issue of The Volunteer we introduce two members of the ALBA community.

Evelyn Scaramella

Professor of Spanish Literature at Manhattan College

How did you get interested in Spain and the literature of the Spanish Civil War?

I lived in Madrid for a semester during college and began studying the avant-garde group, the Generation of 1927. Federico García Lorca’s work and the circumstances surrounding his death at the start of the war fascinated me. As an English and Spanish double major, I realized that the war was fruitful ground for comparative and interdisciplinary study. Some of my favorite American authors wrote poems about the war and went to Spain to cover it.

Your work focuses on translation activity between Spanish, American, and English writers who supported the Republican cause. What do you think these writers tell us about the experience of resistance and wartime?

My research will hopefully become a lens through which we can understand the transnational collaboration among leftist writers on both sides of the Atlantic. I focus on the literary and political history behind the decision to translate certain works (for example, Langston Hughes’s translation of Lorca’s Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads)). I think the translation work done on the Republican side was another strategy of resistance that helped to publicize the War’s horrors abroad. What I find most striking is the depth of the personal relationships formed during a short time in Spain. For example, Hughes developed a close friendship with Lorca’s colleague, the poet Rafael Alberti, while they worked to translate Lorca. As they collaborated politically and personally, it’s not surprising that they began to influence each other’s work.

How do you integrate the Tamiment Archive into your teaching? What do your students gain from using them?

I taught a class on the Spanish Civil War at Manhattan College last spring, and we visited the ALBA archives at the Tamiment. Juan Salas gave a wonderfully informative seminar, and pulled materials for the students to look through. I loved seeing the looks on their faces when they saw the Spanish Civil War posters in person for the first time, or read a soldier’s letter to a loved one back home on the original paper. It’s the stories read in the archives that drive them to take ownership of a research topic. The more they sleuth through the material, the more they see the topic in a new light and want to share what they discover.

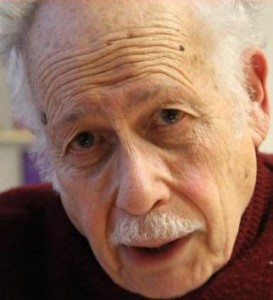

Victor Grossman

Journalist and Author

In 1952, when you were stationed in Germany during the Korean War, you decided to seek refuge in the German Democratic Republic. Why? How did you get to East Germany?

I made the fateful decision only because, after fearfully concealing my nasty leftwing past from the Army by signing the loyalty oath when drafted, they caught up with me. The punishment for lying was up to five years in prison (and $10,000). I panicked at the thought of Leavenworth and took off, not for the GDR—just away! My flight involved swimming across the Danube from the USA-Zone to the Soviet Zone of Austria (at Linz). The Soviets sent me to East Germany.

How was life in East Germany?

It was actually fascinating; plenty of disappointments, problems—as anywhere—but plenty of satisfactions as a lucky husband, father and only human with diplomas from Harvard and Karl Marx University and a life (as freelance journalist); more normal than media-influenced people in “the West” could imagine.

You continue to be critical of German unification. Why?

Despite lots of crap, blunders, stupidity, sometimes roughness, the GDR was an attempt at an anti-fascist state, with job security, home security, women’s equality, no money worries about medical care, education, child care, birth control. With unification we can buy anything we can afford, travel anywhere we want, vote. But the rest is gone (including much of the anti-fascism); Krupp, Siemens, the Deutsche Bank and other criminal firms are back—and keep spreading!

You have met many of the veterans of the Spanish Civil War. Could you tell us how you met them and what their experiences have meant to you?

I grew up with Spain in my heart. In 1961, I was an interpreter for many Lincoln vets in East Berlin: Bill Bailey, Milt Wolff, Moe Fishman, Ruth Davidow, etc. Now I am active in the German “Fighters and Friends of the Spanish Republic” (the last fighter died 2012). I also published a book about the Spanish War, in German!

Victor Grossman’s autobiography, Crossing the River: A Memoir of the American Left, the Cold War, and Life in East Germany was published by the University of Massachusetts Press (2003).

Aaron Retish is associate professor of history at Wayne State University and a board member of ALBA.