Book review: The English captain

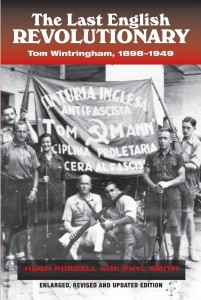

The Last English Revolutionary: Tom Wintringham, 1898-1949 (Brighton, Portland, Toronto: Sussex Academic Press, 2012), by Hugh Purcell with Phyll Smith.

The Last English Revolutionary: Tom Wintringham, 1898-1949 (Brighton, Portland, Toronto: Sussex Academic Press, 2012), by Hugh Purcell with Phyll Smith.

This is a very welcome “enlarged, revised and updated edition” of the biography of Tom Wintringham published originally in 2004. It is sponsored by the Cañada Blanch Centre for Contemporary Spanish Studies, a foundation which supports a series of publications edited by the most important English scholar of the Spanish Civil War, Paul Preston. For the readers of the Volunteer, Wintringham’s greatest claim to fame is his being the English Captain, as his powerful memoir of 1939 was entitled. He served as a Captain in the British Battalion of the International Brigade and played a crucial part in the battle of Jarama, where so many British lost their lives. (Appropriately, this book begins with that battle.) He was wounded twice in Spain but survived to bring the legacy and lessons of the Civil War back to Britain.

Spain was no doubt the most dramatic part of his life. But his story is also very illuminating about the Left in Britain in the twentieth century. He was born into a prominent and well off professional family in Grimsby that was Liberal in politics and Non-Conformist in religion. He went to an English Public School, Gresham’s Holt, fought in the First World War, and studied history at Balliol College, Oxford. He might well have been a successful member of the English upper middle classes. But instead he became a devout Marxist, based on his reading of Marx at Oxford; he joined the Communist Party in 1920, the year of its founding. He was a central figure in its early history, among other activities writing for the Workers’ Weekly, the predecessor of the Daily Worker. For articles in that publication, he was found guilty of sedition in 1925—undermining the morale of the military—and refusing to leave the Party to escape sentencing he went to prison for six months. Even before Spain, he had an intense interest in war and was probably the most talented figure on the far Left able to write on military questions. But his relation with the Communist leadership was a bit rocky both because of his upper bourgeois origins and the leadership’s puritanical disapproval of his promiscuity.

As a committed Communist and military strategist, it was hardly surprising that he went to Spain in August 1936. He led the British at the battle of Jarama in February 1937, was wounded but recovered sufficiently to fight in the Aragon offensive in August. There he was more severely wounded and was sent home. While in Spain, he met an American journalist and idiosyncratic Communist, Kitty Bowker, who was to become his second wife. He was still married to an orthodox English communist doctor as well as having formed another liaison and having children by both women. The party leadership disapproved of his relationship with Kitty, whom it accused of being a Trotskyite, and informed Wintringham that he had either to leave her or be expelled from the Party. He chose the latter course. But he never abandoned his Marxist views and he preserved some admiration for Stalin, dying before the revelations of the 1950s. Yet he disapproved of the British Party’s subservience to Moscow. In 1941 he summed up his views and what Spain meant to him: “Two bullets and typhoid gave me time to think. I came out of Spain believing, as I still believe, in a more humane humanism, in a more radical democracy, and in a revolution of some sort as necessary to give the ordinary people a chance to beat Fascism. Marxism makes sense to me, but the ‘Party Line’ doesn’t.”

Even before Spain, his interests in military questions were intense but undoubtedly his second personal experience of war was crucial in shaping them. This led directly to his greatest claim to fame: his being a founder of the Home Guard. During the Second World War he produced quite a few studies about how to fight, such as New Ways of War (1940) described as “a do-it-yourself guide to killing people.” There was very good reason to think that Britain might be invaded in the war’s early years. Wintringham argued that unconventional guerrilla warfare would prove necessary. At first not supported by the Government, but rather financially by Edward Hulton, who ran the immensely popular Picture Post, and for the training of the Home Guard by the Earl of Jersey who lent Osterley Park outside of London. His “patriotic socialism,” an approach he shared with George Orwell, came into its own in his leadership of the Home Guard, not only in person but in his books and numerous articles he wrote and as military correspondent for the Daily Mirror. His activities were a crucial part of the idea of a “People’s War,” a concept that owed a lot to his experiences in Spain. Eventually the War Office undermined his activities; he was a suspect figure both from the Left and the Right. He played an important part in preparing the way for the defeat of Churchill’s government after the war in his short book, Your M.P. (1944). It argued that not only Neville Chamberlain and his colleagues were “guilty men,” but that rank-and-file Tory M.Ps were not to be trusted to shape a new society. He joined the rather eccentric left-wing party, Common Wealth and twice was almost elected to Parliament. Wartime in Spain and Britain were his greatest moments; he ceased to be a well-known figure after the war, dying prematurely in 1949. It is a fascinating story and is very well told here.

Peter Stansky, with William Abrahams, has just published Julian Bell: From Bloomsbury to the Spanish Civil War.

A useful review to the new edition of this important book on an incredible person all round.. However, the cover shown on this review is that of the first edition rather than the new edition with a red spine and the famous photo of Tom Wintringham and Dave Marshall and others with the Tom Mann Centuria banner taken in Barcelona in 1936. Just in case someone is looking hopefully for it in a bookshop! The second edition is the better of the two, I would say.

Alan Warren

Thanks for catching the picture error, Alan. It´s fixed now.