A Chinese volunteer in the Lincoln Brigade

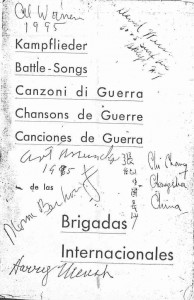

Three Chinese volunteers of the International Brigades at a hospital in Spain, 1938. (L-R): Ching Siu Ling (谢唯进), Hua Feng Liu (刘华封) and Chi Chang (张纪). Tamiment Library, NYU, VALB Photo Collection ALBA PHOTO 15, Series IA, Box 3 Folder 114.

Among the nearly 3,000 U.S. volunteers who joined the International Brigades in Spain, there were two Chinese: Chi Chang (张纪) from Minnesota and Dong Hong Yick (his Chinese name: 陈文饶, Wen Rao Chen) from New York’s Chinatown. Chang survived the Spanish Civil War, but Yick was killed at Gandesa in 1938. Chi Chang came from Hunan, China to study in the U.S. in 1918. He received a degree in mining engineering at the University of Minnesota in 1923. After the Wall Street financial crash in 1929 he endured several hardships, including the loss of his job and a serious illness. In time, he became radicalized, participated in left politics in Duluth, Minnesota, and decided to devote his life to the cause of social justice. In March 1937, Chi Chang boarded the S.S. Paris in New York and headed for Spain. He was older than most other American volunteers. At age 37, he was lanky and weak, but miraculously he managed to cross the Pyrenees on foot. The journey took a heavy toll on his health. He had to give up his initial assignment as a truck driver, and instead worked at a training school. But soon he became ill and was hospitalized for four months. In the fall of 1938, he left Spain for Paris and eventually arrived in Hong Kong to help China fight against the Japanese invasion. The U.S. newspaper The Worker published his picture on December 10, 1944 with the caption: “Chi Chang, pill-box engineer in Spain, now with the Chinese 8th Route Army.” His American comrades remembered him long afterwards. In 1986, during a visit to China, Lincoln Brigade veteran Curley Mende went to the Chinese Communist Party Headquarters to seek the whereabouts of Chi Chang but to no avail. During his stay in Hong Kong in 1939, Chi Chang published “Spanish Vignettes,” a memoir of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War. Here is an excerpt from this work.

Spanish Vignettes

By Chi Chang (张纪)

A Peasant of Spain

The heat of the June sun became hotter and hotter as I traveled further north, driving a giant truck from Valencia to Albacete [Albecete in original text]. Transportation of meat in that scorching weather without a refrigerator required speed. On a treacherously winding stretch of the road I spied through the olive trees a donkey cart and a dark jacketed peasant, ambling along leisurely right in the middle of a sharp turn. My frantic tooting of the horn produced no response either from the burro or its master, and when I succeeded in stopping the truck perilously close to the back of the little two-wheeled vehicle, I was ready to swear away the lives of several peasants. The old man turned around his deeply-lined face, all wrinkled with smiles. To show his proud recognition of an International Brigade man, he raised his right fist high in the air and gave a long shout: “Salud, camarada!” The only swearing I was capable of was the raising of my right fist.

Children of Madrid

Motor trouble. I had to stop in a rather quiet section of Madrid to clean out the fuel pump and the carburetor. In a few minutes a couple of boys stuck their heads under the bonnet beside mine. They were about the same age, twelve or thirteen. My enjoyment of answering in broken Spanish the eager questions shot at me about the automobile was suddenly interrupted by the sound of explosions. I asked the boys: “Aren’t you afraid?” “No,” said one of them, and the other one explained: “Those shells will not drop over this way today.” “Tu Chino?” (“You Chinese?”) he asked, and I nodded. He then said: “¡Chicos en China bombardeados también! Fascistas, no bueno, por todo el mundo.” (“Little ones in China are bombed too! Fascists, no good, all over the world.”)

Waino, the Bartender

The Fifteenth Brigade was passing Albacete on its way to a rest, and I went to look for another Chinese who was in the infantry. [This is Wen Rao Chen (alias Dong Hong Yick) from New York’s Chinatown.] I was told that the big toe of his right foot had been shot off and he was in hospital. As this was being explained to me a fat man ran forward and pumped my hand vigorously. It took me a long time to recognize the face behind the heavy blonde whiskers as that of Waino, the bar-tender at a place in a northern Minnesota town where I used to buy my drink. This was what he told me: “By God, I am glad to see you. Heard that you were around here somewhere. Still drinking much? No? Coming to join us soon? What’s the matter with truck driving? No action, yep. Say, didn’t you know that I came in on the City of Barcelona, the boat that was sunk by an Italian submarine? There were sixty Americans and a couple of hundred others from different countries. I was lucky to grab hold of a life saver. What a sight! The whole sea seemed to be covered with men. I was shaking like a leaf, but those communists! You know what they did? They started singing the ‘Internationale’ in nearly every cocky-eyed language you ever heard. I did not know what it was, but it did me a lot of good. I know the tune now. I am going to be a communist when I get back to America, damned right.” But Waino was killed by a Fascist bullet.

Charlie, the U.S.Marine

I went into the infantry. During training I was assigned to work with the topographical section of the staff. In the same barracks I came to know Charlie [Barr] the twenty-one year old United States Marine and National Guardsman. Through strike action and trips to Nicaragua, Charlie came to be an anti-Fascist. He was one of the best shots at the base and was made an instructor of target shooting. He came in one night after the “taps,” drunk and mumbling to himself: “To hell with everything, I don’t wanna go to the officers’ training school, I wanna go to the front, like a soldier, soldier, you understand? To hell with the Major, I am gonna run away.” He had probably had four or five glasses of vermouth at the canteen. But the Major knew his man. He changed his mind about Charlie, and put him in charge of a sniping group. That was how he went to the front. As a goodbye he told me: “Wait till I get back. We are going together to China. I’ll show you how to kill the Japs.”

Return to Paris

Paris after four months of sickness in Spain. Paris is very beautiful in summer even to a man with bad legs. The newspapers frequently referred to the death of the Popular Front, but in reality it was very much alive under the surface. Every time a train-load of volunteers arrived from Spain, the station and the boulevard in front were crowded with thousands of French trade union men carrying banners and flowers, welcoming these foreigners for whom the French government were making things very miserable. No, the Popular Front is far from dead in Paris.

At the time I was there, negotiations had just been completed whereby fourteen American prisoners from Franco’s concentration camp had been exchanged for the same number of Italian aviators. These Americans were to leave Paris the next day, and a friend of mine was among them. I went to the station to see him off, and found that he had been wounded at the Jarama front early in 1937. Several months of Italian treatment had reduced him to but skin and bones. Suddenly a very neatly dressed man jumped out from the next compartment and threw his arms around my neck. “Hello, Chi, don’t you recognize me any more? This is nothing, I only lost an eye, that’s all, and I didn’t mind the prison life either.” It was Charlie, the young Marine. While at the front, he had been assigned to lead a party of snipers, and from a rocky hill-side they had done some very damaging work against the enemy. Since they were separated from the main force, they did not receive the orders to retreat in time, and they continued their effective work in preventing the Fascists from setting up an anti-tank gun, killing or wounding some forty of the enemy. The Fascists eventually sent two planes to get this group of fifteen men, and by this time the brigade had retreated, leaving them behind. They were finally surrounded, and Charlie was the only one left to tell the story. I had been told previously that he must be dead. “When Youngblood was killed,” he continued, “I was really mad. But I could do nothing, they were all around and on the rock we never could dig in anyhow. Then I got hit. For a while I could not see out of my good eye either. Someone was shouting in Spanish at me. I reached over and grabbed a couple of grenades and made as though I was going to throw them toward where the shouting came from. That saved my life. They said they wouldn’t kill me if I let them take me a prisoner. Well, here I am, still got my shooting eye in good shape. Say, that trip to China still goes with me, if they will take me with my other headlight out. So long, old boy!”

The author, an American-trained mining engineer, was with the International Brigade in Spain for more than a year. – Ed. of Tien-Xia

Source: Tien-Xia, vol. VIII, no. 3 (Hong Kong, March 1939): 235-242.

Nancy Tsou and Len Tsou are the authors of the book (in Chinese) The Call of Spain: The Chinese Volunteers in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939).

Thank you so much for this account. Information on the Chinese volunteers was almost non-existent until Len and Nancy Tsou published their work. So grateful, an invaluable help in my research!

My older sisters had several of their friends in the Lincoln Brigade. Luckily they all returned. They told many storys of the fascists . Franco’s grave is well lit and cared for. When I was in Spain I saw it thru the rear view mirror of my tour bus. These were brave men who fought the good fight

A great story that truly reveals the international solidarity of the global progressive movement in the 1930s. A Chinese immigrant who became radicalized in the U.S. during the Great Depression, Chi Chang went to Spain to help fight against Fascism, and then connecting with others(including a U.S. Marine-turned-anti-Fascist) who offered to help China’s fight against Japanese Imperialism. Is there a better example of inspirational socialist internationalism? Someone should make a film of this amazingly compelling adventure! Bravo for ALBA to bring out another episode of the really “Good Fight”!

Peace & Imua(‘forward’ in Hawaiian)from a midPac Peace activist.

Excellent information. I am currently researching foreign volunteers in foreign wars for a forthcoming book.

Peace.

I am the publisher of a non-profit quarterly magazine, Chinese American Forum, and would like to reprint “A Chinese volunteer in the Lincoln Brigade, January 4, 2013, By Nancy Tsou and Len Tsou” in my 2012 April issue.

Your permission is greatly appreciated.

C C Tien

03/29/2013

Hi, Mr. and Mrs. Tsou, I’m Lindsay from a TV production Company in Shanghai, China. We’re going to make a travel TV show. And on episode is about Madrid.

We want to interview a veteran during our shooting in Madrid who took part in the Spanish Civil war. And it would be very meaningful if we can find someone who just know something or once met with our Chinese Volunteer from the international brigade.

Thus I found here and your article, May I ask if you have any information about people knows these Chinese soldiers in Spain?

It would be a great help if I can receive your reply.

[…] How is it that in the 21st century – when technology is often said to have shrunk the world and made global humanity far more interconnected – that there is so little awareness of or support for the revolution in the rebel-held territories within Syria? When Spanish Republicans, socialists, and anarchists were fighting Franco, the international left not only recognized the revolution, despite ostensible Western support (in reality, very halting) for the anti-Francoists, but demonstrated real solidarity, sending soldiers from all over the world, including the Abraham Lincoln Brigade from the U.S., and from citizens as far away as China and other parts of Asia. […]

Hello, I wonder if you know a bit about Gopal Huddar from India; He was my wife’s grand father

In Castelldefels died in the summer of 1938, possibly a victim of abuse, an American of Chinese origin (probably) called Sensen Semfley (or similar), which I can’t find data about him (only in Eby and in http://dialnet.unirioja.en/download/article/4042357.pdf and on other sites). As if out of interest, has published a history of some Chinese volunteers who fought in Spain (I have not read, is quoted here http://www.elconfidencial.com/cultura/2013/05/25/los-Chinese-you-fought-in-civil-war-121608)

Interesting note about Chang. There are lots of important, but repressed, stories about Chinese at war in Europe: for example, tens (hundreds?) of thousands of Chinese labourers were transported in secret in sealed trains and shipped to the Great War where they dug huge tunnels (many abandoned but still there), trenches, campsites, railroads, etc. as well as cooking and washing. After the betrayal of the Chinese in Paris at the Versailles Treaty talks, some Chinese went back to China; some were leaders of the 1919 May 4th Movement – and many Chinese stayed on in Europe maybe later suffering through WW II. Many Chinese must have fought in the Russian Revolution too, but there is very little info about that. Actually, Chinese must be some part of almost everything.

A Chinese video maker had made and uploaded a video about Chinese people who joined in the International Brigade and that video has been attracted many people to learn about these pieces of histories,and many of them even do not know there was these group of Chinese fighted for Spain.

Nowadays,people usually think that the races,nations and so on are above all of their life.But few one would like to discover those people who has been forgotten.