Wikileaks, avant la Wiki: FDR on Franco in 1945 (2)

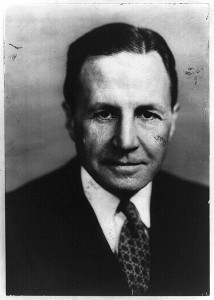

Norman Armour, career diplomat, was the US Ambassador to Spain during the prickly months and weeks of 1945.

In a previous post I somewhat flippantly evoked the Wikileaks brouhaha in order to present an interesting diplomatic document I had stumbled across in Jon Cowan’s excellent Modern Spain: A Documentary History. The document was a letter written by FDR in March of 1945 to the new US Ambassador in Madrid, N. Armour. The letter basically says that the US government will hold its nose and maintain relations with the Franco regime, but that it repudiates the origins and ideology of the regime, vividly recalls the close wartime alliance of Franco with the Rome-Berlin axis, and, in particular, abhors the prominence of the Falange, the fascist party, in Franco’s government.

Little did I know when I made that throw-away wikileaks quip that this brief archival document actually was involved in a major diplomatic scandal in 1945 involving “leaks.” And as I worked in the library this morning trying to untangle the snarl of wires and cables that is diplomatic history, it struck me that what was at stake in this scandal from 65 years ago are many of the very same issues that are being played out today in the wake of the wikileaks, in Cairo, in Tunis, in Madrid and elsewhere. “Who gets to know what?” Here is a succinct chronology of the kerfuffle:

10 March 1945

Roosevelt writes letter of instruction to new American Ambassador in Madrid

12 April

In a meeting with Spain’s Foreign Minister Lequerica, Armour reads Roosevelt’s letter aloud, “stressing particularly the last four paragraphs”

26 September

Roosevelt’s letter of instruction to Armour is released to the US press.

30 September

US Embassy in Spain publishes the text of Roosevelt’s letter in a “confidential bulletin sent to high Spanish officials and certain Spaniards outside of Government.”

The Spanish Foreign Ministry quickly expresses “indignation over publication which they considered unethical… […arguing] that it was unprecedented to make public confidential instructions of this nature.”

In his report to the State Department, Ambassador Armour astutely interprets this indignation: “It is clear that the Government here had hoped to be able to keep Spanish public including their own supporters in ignorance of the true attitude of our Government toward Franco regime… What apparently worries [Spanish] Government most is that statement is a unilateral one by our Government, as Churchill letter was of British Government, in contrast with San Francisco and Potsdam declarations which were participated in by Soviet and other govts.

Oct. 2

US Acting Secretary of State in Washington gives Ambassador Armour the green light to even further publicize Roosevelt’s articulation of the US wary and nose-pinching stance before the Franco regime by printing it in the Embassy’s bulletin, the Semanario Gráfico. The rationale coming from the State Department: “One of the reasons behind release of President Roosevelt’s letter was to let the Spanish people know our attitude toward Franco and the Falange. We feel therefore that you should proceed with publication in Embassy Bulletin. We can probably meet any difficulties Franco might make for the Embassy.”

October 3

Release of issue of Semanario Gráfico containing Roosevelt’s letter

October 10

The difficulties foreseen by the Embassy and the State Department don’t take long to materialize. Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs sends angry communiqué to the US Embassy, quoting at length from a dispatch filed by the Madrid correspondent of the United Press, Mr. Forte:

“While General Franco today convoked his Government, thousands of Madrid people read for the first time the text of the letter sent by President Roosevelt to the present North American Ambassador in Spain, Norman Armour. This has been possible through the insertion of the text of the letter denouncing the Falange into the Graphic Weekly, published twice a month which is edited in Spanish. 90,000 copies of this publication are issued which are distributed in Madrid and the provinces by the Consulates of the US, and in Madrid it has a wider circulation than any of the local newspapers[…] Scarcely were Spaniards aware that the Embassy had published in its News Bulletin, Semanario Gráfico, the text of the letter.. than they congregated by the hundreds in front of the Embassy, forming lines to obtain a copy of the Bulletin.”

The Ministry goes on to express its hope that the US Embassy “will abstain from reproducing documents or declarations which refer to Spanish policy, the publication of which is not expressly authorized by the Spanish Government.”

October 26

Obviously profoundly perturbed and impatient about Franco’s slowness in de-falangizing his regime, the US ambassador’s closing response is quite a zinger:

The Semanario Gráfico has been distributed in Spain since June, 1943. The issue to which reference is made above is No 113 and was circulated in a manner wholly similar to the previous issues. This publication, insofar as distribution and circulation are concerned, is similar to the publications of other Embassies, including those of the late Axis, which have been circulated in Spain in recent years.

Is it consistent with the relations prevailing between the two Governments for the Spanish Government to prevent either in the Spanish press or in the official bulletin of this Embassy the publication of statements by the President or other high officials of the Government of the United States? No such restrictions exist in the United States on the publication of statement of the Spanish Chief of State or of other Spanish officials.

All documents cited here can be found in Volume V (Europe) of Foreign Relations of the United States: Diplomatic Papers, 1945. US Government Printing Office, 1967.

See also a previous and subsequent post on this subject.