Who Is Afraid of the Spanish Civil War? Hollywood Is Still Jittery

Major US films and series about the Spanish Civil War have been few and far between. Why has Hollywood shied away from a topic that, on the face of it, presents such a trove of compelling stories?

Since the fall of the Berlin Wall, major film studios in Los Angeles have spent many millions exploring the moral complexities of World War II—and especially America’s entry into the conflict—in series such as Band of Brothers (2001), The Pacific (2010), and Masters of the Air (2024), or in feature films like Schindler’s List (1993), Inglorious Basterds (2009), The Monuments Men (2014), and Oppenheimer (2023). By comparison, projects about the Spanish Civil War have been few and far between—as they were for most of the Cold War.

Why has Hollywood shied away from a topic that, on the face of it, presents such a trove of compelling stories? Are there no passionate screenwriters and filmmakers interested in telling them? In fact, there are plenty, as I discovered during my own development of a historical-fiction feature film about George Orwell’s experiences in Spain. Yet, somehow, promising Hollywood projects on the Spanish war consistently run aground. Some recent examples:

- In 2018, David Simon—the creator and writer of what many consider the single best television series ever made, The Wire (2002)—announced to the Hollywood press that he was writing A Dry Run, about “a group of Americans who travel to Spain to fight for the republic against Francisco Franco’s Nationalists” in the “Abraham Lincoln and George Washington battalions”. The “Spanish struggle against fascism,” Simon told Variety, “and the misuse of capitalism as a bulwark to totalitarianism,” are “the pre-eminent political narrative of the 20th century, and of our time still.” Since then, however, public information about the project— a coproduction between HBO and the Spanish company Mediapro—has been scarce. In a 2022 interview with Culture Magazine, Simon mentioned that he was still researching and writing scripts. On the IMDB website, production has been listed as being “in development” for years, with two high-profile writers, George Pelecanos and Dennis Lehane, included in the team. Yet there is no sign that the series is any closer to production than it was seven years ago.

- Michael Mann, the Academy Award-nominated director of Heat, collaborated with Hollywood studio Columbia Pictures (owned by Sony) on the adaptation of Susana Fortes’ novel Waiting for Robert Capa (2009), which tells the story of the romantic and professional relationship between Capa and Gerda Taro as war photographers in Spain. Although that project went as far as casting Andrew Garfield and Gemma Arterton as the two leads, it withered on the vine.

- Adam Hochschild confirmed to me that his book Spain in Our Hearts (2016), which also deals with the American volunteers, was optioned by a Hollywood television company—but it never advanced to production.

- My own Orwell feature film, set in Spain—which was once under development by the same company that produced Blood Diamond—has yet to be made. I have continued working on the project for years because I believe that Orwell’s legacy and his experiences in Spain make for a thrilling story that has much to say to us today. (More recently, I have also been consulting with researcher Bernd Haber, who seeks to tell the story of his great uncle, Hans Maslowski, a volunteer with the International Brigades.)

Why have none of these projects made it to the screen?

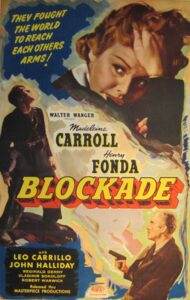

The Spanish Civil War has long been a challenging and complex subject for Hollywood films. Even in 1938, during the conflict, the feature film Blockade was met with protest by the American Catholic Church and banned in some American cities, despite the fact that it pulled its punches and never even mentioned Spain, let alone the enemy to the Republican cause. In The Fallen Sparrow (1943), the hero, played by John Garfield, suffers from the trauma of being tortured as a fighter in Spain, although German Nazis emerge as the true enemy in the World War II plot. The biggest success story was the film version of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943), based on the Ernest Hemingway novel. It earned a hefty profit and was nominated for nine Academy Awards. Released as it was after the attack on Pearl Harbor, it struck a chord with audiences as the US was fighting fascism on multiple fronts.

The situation is different today. In Hollywood, there are usually two reasons why promising films are not produced. The first is business-related. Historical fiction films or TV series, also known as period pieces, are typically expensive to make, given the cost of creating historically accurate sets, costumes, and props. War stories are even more expensive due to the large numbers of soldiers and visual effects needed to portray battle scenes convincingly. Recreating a visually stunning and accurate film version of the Spanish Civil War, in other words, would almost inevitably require a large budget. One way Hollywood has attempted to mitigate risky financial outlays is by seeking out popular books that can serve as the basis for a project—and as proof that an interested audience exists. (Schindler’s List, for example, was based on the book Schindler’s Ark by Thomas Keneally, and Oppenheimer on the biography American Prometheus by Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin.) Moreover, many Hollywood executives are concerned that the complexities of the Spanish Civil War will deter the audience, although predicting box office is notoriously difficult. The challenging, dramatic film Oppenheimer, about a scientist involved in a controversial historical subject (and, incidentally, married to the widow of a Spanish Civil War veteran), was predicted to underperform. Instead, it became a runaway success, grossing almost a billion dollars worldwide. Oppenheimer shows that cinema audiences often respond to original stories and are eager for new experiences.

The second major make-or-break factor in Hollywood is the subjective, “creative” analysis of a project by the studio leadership. How good is the script? Is it attractive to top actors? Does it have a shot at major festival prizes, or even an Academy Award? The Republican side of the Spanish war—especially the international volunteers who left their countries and sacrificed so much to fight against totalitarianism and for ideals of freedom, democracy, and equality—would seem to fit the bill: they provide powerful, thought-provoking stories, inviting nuanced, powerful acting performances. In a world where authoritarianism is on the rise and democracy imperiled, many potential moviegoers would recognize these stories as vitally important.

And yet this is precisely what scares the Hollywood studio execs, whose conventional wisdom on the Spanish War is that any portrayal of Republicans by necessity has to address Communism, Socialism, and Anarchism. However much creatives tend to claim that “controversy sells,” the corporate ecosystem of Hollywood has little appetite to stake a large financial risk on a story about revolutionary antifascists. When so much money is riding on a single project, funders are less likely to embrace a topic that, inevitably, will be read as a critique of late-stage capitalism—challenging or even angering a sizable share of the American audience, not to mention the political and corporate stakeholders of Hollywood studios.

One relatively recent exception to this trend was Philip Kaufman’s HBO-produced TV movie Hemingway & Gellhorn (2012). According to press reports at the time, the fame of Ernest Hemingway—and the casting of Clive Owen and Nicole Kidman in the starring roles—convinced HBO (then owned by Time-Warner) to greenlight the film at a budget of $15-18 million. Although we see Hemingway working on The Spanish Earth while Martha Gellhorn discovers her passion for war reporting, the film glosses over the politics of the Spanish war, reducing it to the backdrop of a love story and, at most, presenting it as a precursor to World War II. In the end, it was an opportunity lost—all the more so considering that a subscription-only network like HBO allowed their shows to be more edgy and independent than any theatrical release.

Since Trump’s second electoral victory, the political climate in Hollywood has only chilled further. The temporary removal of Jimmy Kimmel’s talk show from the air illustrates how a consideration that was once kept behind closed doors has become public policy. In the last issue of The Volunteer, historian Kirsten Weld argued that some of the intellectual roots of American ethnonationalism can be traced back to the reactionary traditions that inspired Franco’s regime. In this context, any film about the Spanish war featuring the Republicans would likely be seen as too risky a threat.

But fortunately, Hollywood is not the only game in town. The projects on the Spanish war that have made it to the theaters over the past 35 years have generally been small and independent. Ken Loach’s feature film Land and Freedom (1995), loosely inspired by Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia, had a reported budget of US$3.8 million. Academy Award winner Roland Joffé’s There Be Dragons (2011), which depicts both sides of the conflict, was largely financed by Opus Dei, since it featured Josemaría Escrivá, the founder of that religious order, as its main character.

Of course, there have also been plenty of Spanish (co-)productions that grapple with the war and the Franco years. Best known in North America are two films by Mexico’s Guillermo Del Toro: The Devil’s Backbone (2001) and Pan’s Labyrinth (2006). Other, more recent films such as The Endless Trench (2019), While at War (2019), and The Teacher Who Promised the Sea (2023), show that the war continues to inspire Spanish filmmakers.

In Hollywood, industry concerns could continue to hinder the production of films about the Spanish Civil War. At the same time that the box office revenue for dramatic, complex feature films in the United States is steadily declining, the golden era of “peak TV,” when complicated characters and dark subjects were widely explored in cable and streaming series, is no longer seen as financially viable. Meanwhile, a new wave of media consolidation, including the proposed sale of Warner Bros. to Netflix, will further discourage the production of controversial projects—and even theatrical films altogether.

If the jitters about the Spanish war are primarily a Los Angeles problem, the steady decline of Hollywood hegemony is a source of hope. Of course, major studio productions still command a far higher production and marketing budget, not to mention guaranteed distribution, increasing their odds of creating a global cultural moment. However, as current trends in film financing and production are eroding the traditional lines of demarcation between Hollywood and the rest of the world, new opportunities may be emerging for English-language films or series set in Spain. For example, Spain has developed a robust film industry, supported by government tax credits and excellent crews. (Artificial Intelligence is also, controversially, projected to bring down the costs of special effects such as those used to replace modern objects and buildings, or create the visual world of a battle scene.)

Like with so many projects in Hollywood and elsewhere, if brave and determined trailblazers dare to show the way and succeed, then others will follow. It will likely take the full-throated support of a well-known actor or director for any project on the Spanish war to make it to production. Such support is perhaps likelier now than in recent years. Today, a powerful film or series about the Spanish fight against fascism could inform and inspire many.

Christopher Angel is a filmmaker and screenwriter based in Los Angeles. A graduate of Yale and the University of Southern California School of Cinema, he won a student Academy Award, was nominated for an Emmy, and has directed five feature films. He is adapting William Abrahams and Peter Stansky’s Orwell: The Transformation for the screen.