Teaching the International Brigades: A Report from Barcelona

What is it like for Spanish high school students to learn about the International Brigades today? History teacher Ioseba Landa reports from the trenches.

In my work with secondary school students in Barcelona over the years, I have sought to transform antifascist history into a living tool for learning, activism, and reflection. Teaching the history of the Spanish Civil War and the International Brigades in Spain and elsewhere amounts to much more than covering a historical period. It presents an opportunity to connect past and present, educate students in democratic values, and foster critical awareness in the face of contemporary global challenges.

These same goals have inspired “The Passage of the International Brigades through Barcelona,” in which students spend five weeks researching the International Brigades, culminating in the creation of a mural. I developed the unit in collaboration with the artist Roc Blackblock, who recovers historical memory through urban art, working with institutions such as the Catalan Association of Friends of the IB (ABIC) and the Resource Center of the University (CRAI) of Barcelona. (The CRAI also manages SIDBRINT, the world’s largest online International Brigades database.) [See here for an interview with Roc Blackblock in a previous issue of The Volunteer.]

In my history classroom, I present the International Brigades as an extraordinary historical expression of international solidarity. When my students hear about the thousands of volunteers from all over the world who chose to defend the Spanish Republic against the fascist threat, immediate questions come up: Why would someone leave their home to fight in a distant war? What values motivated them? What does international solidarity mean today?

Our classroom work is based on primary sources, including testimonies of brigadiers such as the Irishman Liam McGregor or the Dutchman Evert Ruivenkamp, speeches by figures like Juan Negrín or Dolores Ibárruri, “La Pasionaria,” and archival materials accessed through SIDBRINT. Sources like these humanize the conflict, allowing students to move beyond an abstract or simplified view of the Civil War. As they explore biographies, photographs, letters, and personal stories, the past stops feeling distant or foreign.

A central focus of the project is the diversity within the International Brigades. We specifically discuss the role of women as well as nurses, journalists, soldiers, translators, and activists from marginalized racial, social, and cultural backgrounds. The narratives that emerge challenge dominant historical accounts, paving the way for a more inclusive account of the past. This perspective also connects directly with students’ own concerns and daily life in a diverse and multicultural city.

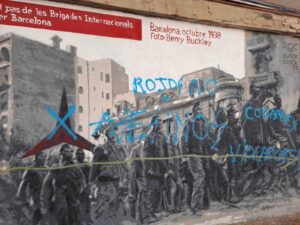

The project’s aim is not just to learn about the Civil War, but to think about it, debate it, and reinterpret it. Roc Blackblock’s urban art serves as a key pedagogical tool, transforming public spaces into sites of memory. While Roc paints the mural with stencils based on historical photographs, the students research the historical meaning of the images and create informational content. As visual narratives, the murals engage the community, prompting questions among residents and passersby.

Joining in the process of artistic creation helps students understand that memory is neither neutral nor fixed; it is constructed and contested. Deciding what to represent, how, and why requires critical reflection on both past and present. Moreover, leaving a visible mark on their surroundings strengthens students’ connection to local history, turning them into active agents of memory. Even experiencing vandalism—murals are regularly defaced by far-right graffiti—has helped heighten students’ awareness of the continuing relevance of these historical issues—including the persistence of intolerance and fascism.

Indeed, a core aspect of our classroom work is focused on the present. The International Brigades serve as a springboard for discussing the rise of the far right, current armed conflicts, refugee movements, and new forms of international solidarity. Students are invited to consider to what extent the ethical values and commitment that motivated the brigadiers remain relevant today.

My public school, the Instituto Quatre Cantons in Poblenou, Barcelona, employs a project-based curriculum, providing significantly more time for projects like these—five weeks, to be precise—than schools following the standard curriculum. This is not to say we don’t face limitations. Even for us, class time is often insufficient to fully develop all aspects of the project, and access to artistic or material resources is not always easy. Moreover, working on historical memory—still a sensitive topic in Spanish society today—can generate tensions. Still, these challenges are an integral part of the educational process and often present opportunities for debate and critical reflection.

Over the years, I’ve learned that analyzing the Spanish war with the International Brigades as a guiding thread has a profound impact on students—not only in terms of historical knowledge but also in their understanding of democracy, social justice, and personal responsibility in the face of injustice. The historical empathy that is required to step into the shoes of a brigadista helps young people understand that history is made by ordinary people making decisions in extraordinary circumstances.

At a time when fascism is resurging in new forms and discourses, the memory of the International Brigades reminds us that solidarity among peoples is not an abstract idea, but a concrete practice embodied in real names, faces, and stories. Teaching this memory means committing to an education that not only explains the past but also helps build a more just, democratic, and compassionate future.

Ioseba Landa is a history teacher at the Instituto Quatre Cantons in Poblenou (Barcelona) who holds a degree in Political Science and specializes in Contemporary History, including the Spanish war of 1936. Translated by Sebastiaan Faber.