NYU Is Digitizing ALBA’s Civil War Poster Collection

“We Don’t Want Pristine Museum Pieces.”

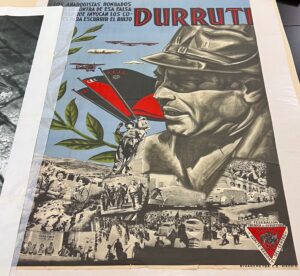

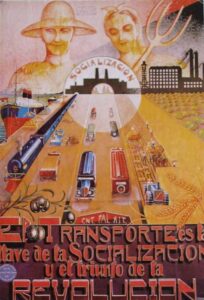

Lindsey Tyne spent much of last summer carefully studying more than two hundred posters from the Spanish Civil War that were first brought to the United States by the surviving veterans of the Lincoln Brigade. “It was an incredibly educational experience,” she told me when we spoke in early January. “These posters represent an amazing moment in graphic design, but also in terms of printing techniques—despite the fact that they were produced under very challenging and urgent circumstances.”

Tyne, a paper conservator and the Conservation Librarian in the Barbara Goldsmith Preservation & Conservation Department at NYU Libraries, is coordinating a major, two-year project to conserve and digitize all the Spanish Civil War posters held at the Tamiment Library. The NYU collection, which comprises over 250 posters, is one of the largest held by any institution outside of Spain, more than twice the size of those at UC San Diego, Brandeis, the Library of Congress, or the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. (By comparison, the University of Barcelona has more than 1,100 posters, while the Spanish Civil War archive in Salamanca boasts more than 2,200.)

Exactly what posters are part of this project?

We’re limiting the scope to posters held at the Tamiment that were produced between 1936 and 1939, either in Spain or in other countries. Most of them were part of the original ALBA collection when it was transferred from Brandeis to NYU in 2000, but some were added later. Excluding duplicates, we’re talking about 230 unique titles that will now be available for physical and remote digital access.

Why conserve and digitize them now?

The main reason is the high level of interest. According to our reading room statistics, our poster collection is among the most heavily used collections. It’s also frequently featured in classroom instruction—plus, we recently sent some of the posters out on loan. In 2024, for example, three of them were featured in the Francesc Tosquelles: Avant-Garde Psychiatry and the Birth of Art Brut exhibit at the Folk Art Museum here in New York City. Before any item can go out on loan, it comes through the Special Collections Conservation Unit, where we assess the item and perform any necessary conservation work. As it happened, I had the opportunity to conserve these three posters myself. Fortunately, they didn’t need major work, just some minor stabilization.

What’s the role of your unit in this project?

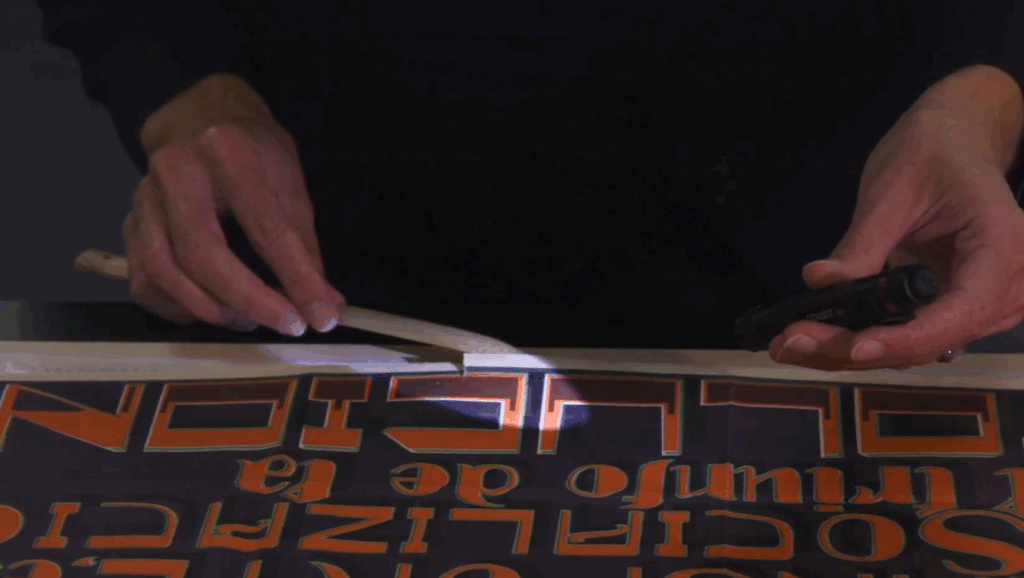

Before our Digital Library Technology Services can start digitizing the posters, for which we fortunately have the equipment and expertise in-house—we have to conserve them. Honestly, that’s the most time-intensive part of the project. In fact, an anonymous donation has allowed us to hire a designated project conservator, Ana Sofia Drinovan. She started this past fall and will be working on the project for two years.

What draws you in personally?

I hope to learn more about the print technology used through the research we will be doing as part of this project. These posters were produced as offset lithographs. What that means is that all the drawings, paintings, text, and photos they include were transferred to printing plates. For multicolor images, moreover, each color had its own plate, which is mind-boggling if you consider how many colors some of these posters include.

What shape is the collection in?

We haven’t finished assessing every poster yet, but I can tell you there is a huge range. I have seen some posters that are in extremely good condition and that just need minor work, such as mending a small tear. Others are in much worse shape: they are missing fragments, or they have broken into several pieces. We shouldn’t forget that these posters were printed under wartime conditions and were meant to be ephemeral items for immediate use. The paper and ink used were not selected for their longevity or preservation!

As a paper conservator, what do you see when you handle objects like these?

I see paper that is machine-made—low-quality, short-fiber paper that, over time, has become discolored and brittle. That’s a problem, especially given the size of these posters: they average about 30 by 40 inches, but some are double that size. Because short-fiber papers don’t have a lot of internal mechanical strength, the posters’ size makes them extremely susceptible to handling damage during routine access. The inks, on the other hand, are oil-based, which was the standard in lithography, and therefore relatively stable in comparison.

What is your conservation treatment philosophy?

Our goal is stabilization for long-term preservation. At the same time, we don’t want to remove any evidence of these posters’ history or use.

What do you mean?

I mean that we do not want to turn the posters into pristine museum pieces. Rather, we want them to read as whole items. How they were used in Spain and how they came to the United States is important information to us. That means we’ll mend tears and losses, but we will not try to make the mends invisible—although if a tear is distracting, we might use some color to make it slightly less so. In some cases, we’ll have to line posters with thin Japanese paper. But we won’t do that unless the poster is so fractured or has so many tears that it really needs it.

All that sounds like a tricky balance to strike.

Absolutely. And we’ll certainly be consulting with Shannon O’Neill, Curator for the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, and other experts worldwide who have worked on collections like these. And of course, we’ll carefully document every step of the process in writing and with photographs. All that said, the simplest but perhaps most important thing we are doing, as a final phase, is encasing the posters in polyester sleeves. That way, anyone handling them can pick them up without a high risk of causing damage.

When and how will the scans be available?

Michael Stasiak, our Digital Content Manager, is overseeing the digitization, which, as I said, will be done in-house. We aim to finish the project in the fall of 2027. The images will be made available on our website through the Spanish Civil War Poster Collection (ALBA.GRAPHICS.001) finding aid as high-resolution, interactive digital images with panning and zooming functions.