The Republic’s Legal Resistance to Fascism

The Republic’s fight against fascism was not limited to the trenches. There was also a quieter, though no less vital front—the judiciary—where the Republic fought to preserve legality, due process, and democratic norms.

In the fall of 1936, Federico Enjuto Ferrán, a 52-year-old Republican judge, instructed the case against José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Falange and one of the principal ideological instigators of the fascist uprising, who was sentenced to death and executed in November. The judge’s memoirs, which will be published for the first time this year, offer a rare window into the legal and moral world of the Spanish Republic as it confronted the coup and worked, against all odds, to uphold the rule of law.

Enjuto’s testimony shows that the Republic fought not only with rifles and militias, but also with judges, clerks, and legal institutions that refused to surrender their principles even as the country collapsed around them. The defense of democracy was not only a matter of armed resistance but also of insisting that justice, even in wartime, must be something more than vengeance or improvisation.

Federico Enjuto Ferrán was not a young jurist thrust prematurely into a crisis. Born in 1884, he was a third-generation magistrate whose family had served on the bench since the nineteenth century. His grandfather and father had both been magistrates in the Spanish Supreme Court—his father even serving in Havana and Puerto Rico during the final decades of Spanish colonial rule before the family returned to Spain in 1900. Thus, Enjuto inherited not only a profession but a tradition: a belief that the law was a craft, a discipline, and a public trust.

By the time he was appointed to instruct the case against José Antonio, he had spent decades in the Spanish legal system, moving through courts in Madrid, Barcelona, and the Balearic Islands, and participating in commissions for civil and penal reform. He was shaped by the slow, meticulous rhythms of judicial life, not political upheaval. It was this procedural temperament that the Republic needed in the summer and fall of 1936.

When the military uprising began in July, José Antonio Primo de Rivera was already in prison, arrested in March on charges of conspiracy and illegal possession of arms. As founder and leader of the Falange, an openly fascist movement that had been agitating for insurrection, he was a symbolic figure for both sides. For the rebels, he was a natural caudillo, the son of Miguel Primo de Rivera, who ruled Spain as a military dictator from 1923 to 1930—but also, potentially, a martyr-in-waiting. For the Republic, he was a dangerous conspirator whose political project aimed to destroy democratic institutions.

Into this volatile situation stepped Enjuto, tasked with instructing the case. He had to gather evidence, interrogate witnesses, evaluate documents, and determine whether the charges could be sustained in court. Under normal circumstances, this would have required technical precision and a steady hand. Under the conditions of civil war, it demanded something more: the composure of a man who understood that the Republic’s credibility depended on the seriousness with which its judges continued their work.

The summer of 1936 was marked by killings on both sides. A mass shooting of right-wing prisoners taken from Madrid’s Cárcel Modelo in August horrified the government and convinced its leaders that the Republic could not survive if violence continued to unfold outside the law. Mariano Gómez, President of the Supreme Court, crafted an ambitious emergency legal framework to bring conspirators, rebels, and suspected collaborators before so-called tribunales populares. These people’s courts were hybrid: while career magistrates presided and guided the proceedings, a fourteen-member popular jury evaluated the evidence and delivered verdicts. The goal was to ensure that people were tried not for their political affiliation, but for their acts, and to channel the fury of a society under attack into a legal process that preserved the Republic’s democratic legitimacy.

Enjuto’s work as instructor in the Primo de Rivera case took place within this broader institutional effort. He was not acting alone or improvising under pressure; he was part of a deliberate policy to replace summary violence with judicial procedure, to transform the Republic’s instinct for survival into a defense of legality. His memoirs show how seriously he took this mandate. He insisted on distinguishing between moral culpability and criminal proof, between ideological leadership and legal responsibility. José Antonio was, without question, a central figure in the coup’s ideological architecture. His speeches, writings, and organizational leadership helped create the climate that enabled the uprising. But the legal question was narrower: could he be held criminally responsible for acts committed while he was in prison?

Enjuto approached this question with the discipline of a jurist who understood that the legitimacy of the Republic depended on its ability to distinguish between political judgment and legal judgment. He sifted through communications, testimonies, and organizational links, reconstructing the broader context of Falangist activity while also acknowledging the gaps—places where the chain of causality was incomplete or where the urgency of war prevented further investigation. His honesty about these limits is one of the memoir’s most powerful features, revealing a Republic struggling to maintain its standards even as the world around it disintegrated.

The pressures on the judicial process were enormous. Changes in the prosecutor’s office, political expectations, attempts to storm the prison cell, and the accelerating tempo of the war all shaped the environment in which Enjuto worked. He describes how deadlines were shortened; how new directives arrived from Madrid and, after the Republic’s government fled the capital, from Valencia; and how the symbolic weight of the case threatened to crush its legal foundations. Yet he also shows how the judiciary resisted: judges insisted on proper documentation, demanded corroboration of testimony, and refused to accept political rhetoric as evidence. They maintained the distinction between the courtroom and the battlefield, even when the two seemed to be collapsing into one another.

This is not to romanticize the Republic’s justice system, which was imperfect, strained, and sometimes inconsistent. Still, Enjuto’s memoirs make clear that there was a real and deliberate effort to preserve legality, even when doing so was politically inconvenient. In this sense, the trial of José Antonio becomes a microcosm of the Republic’s broader struggle: a fight to defend democratic norms against a movement that sought to destroy them. While Franco’s rebels executed thousands without trial, the Republic, even in its darkest hour, tried to build a case.

José Antonio was sentenced to death and executed in November 1936, guilty of conspiracy and military rebellion. His death became a cornerstone of Francoist mythology, but only after a long, enforced silence of two years about the trial and execution on the Nationalist side, which promulgated the legend of the “absent one” (el Ausente). After the war, the dictatorship elevated him to the status of martyr, built monuments in his honor, and used his memory to legitimize its repression. What disappeared from view, meanwhile, was the story of the trial itself—the painstaking work of judges like Enjuto, the debates over evidence, the procedural safeguards, and the attempt to maintain legality in the midst of chaos. Francoism had no interest in preserving that history. It needed a martyr, not a defendant who had been afforded due process by the Republican state.

Enjuto’s memoirs restore that missing chapter. They show that the Republic did not rush to execute José Antonio out of vengeance or ideological hatred. It tried and judged him with a seriousness that stands in stark contrast to the summary executions carried out by the rebels. For readers of The Volunteer, this is a reminder that antifascist resistance took many forms.

After the war, Enjuto—like so many Republican intellectuals—was forced into exile. He eventually settled in Puerto Rico, where he had been born, and he became a respected law professor, editor, and cultural critic. His work there, especially his efforts to build institutions and promote public culture, reflects the same procedural rigor and civic commitment that shaped his judicial career. Exile gave him the distance to reflect on the trial. His memoirs are a meditation on the fragility of institutions, the dangers of political fanaticism, and the responsibility of jurists in times of crisis. At a moment when authoritarian movements around the world seek to undermine legal norms, Enjuto reminds us that the rule of law is a practice sustained by individuals who choose integrity over expediency.

Pedro García-Caro, Associate Professor of Spanish at the University of Oregon, studies how transnational encounters shape culture and politics. His work deals with postcolonialism, nationalism, authoritarianism, extractivism, power, and identity. Together with Cecilia Enjuto-Rangel, he has edited Judge Enjuto’s memoirs, which will be published in Spanish by Comares.

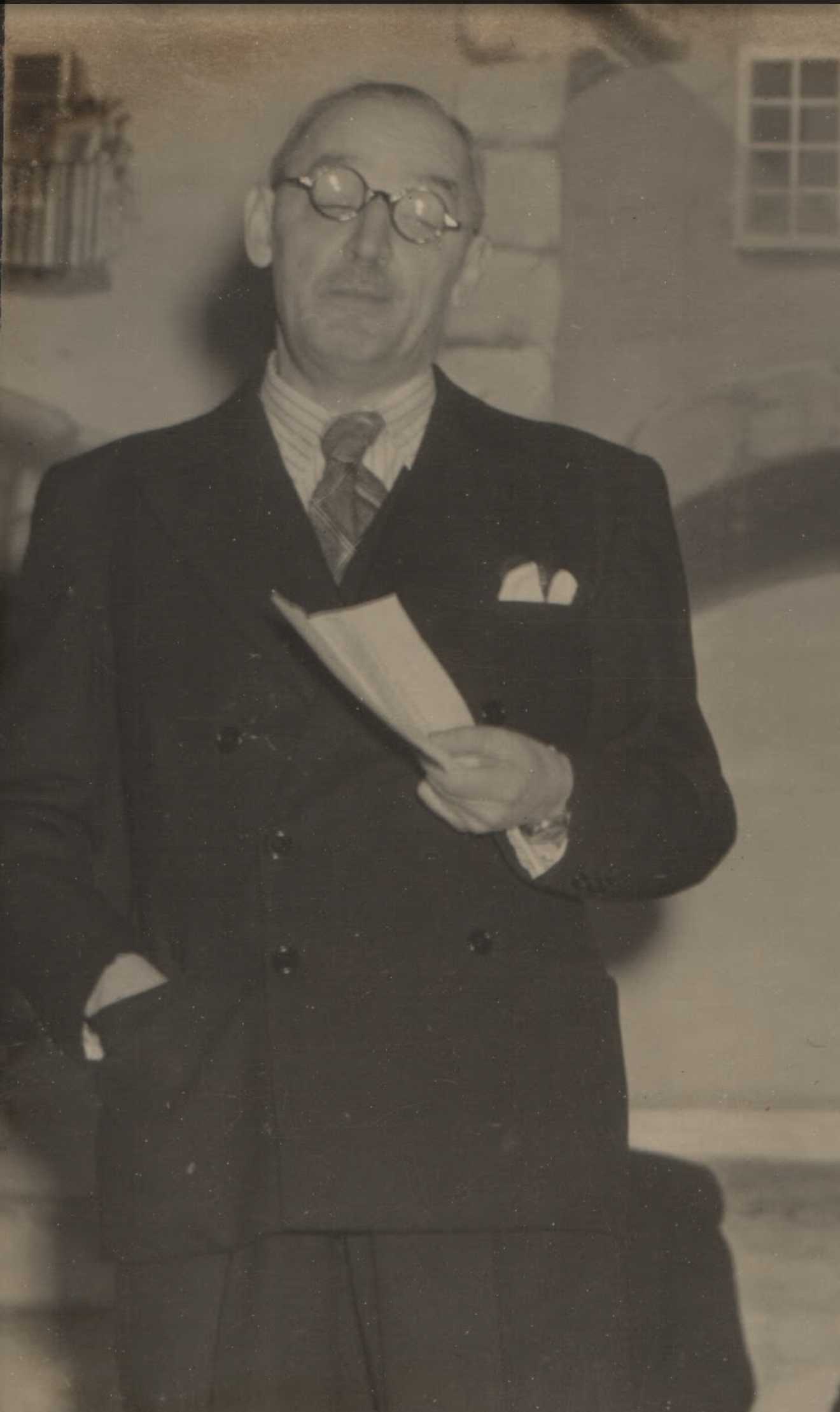

Image: Federico Enjuto Ferrán during a public meeting in New York in early 1940.