Book Review: Giles Tremlett’s Franco Biography

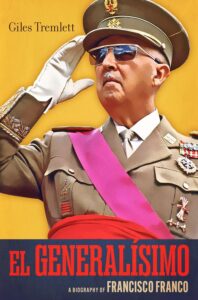

Giles Tremlett, El Generalísimo: a Biography of Francisco Franco. New York: Oxford University Press, 2025. 528pp.

The dictator-biography business has always been good. In 2006, one scholar estimated that there were about 106,000 biographies of Adolf Hitler. If we add the thousand works on Benito Mussolini and an additional 100 or so on Francisco Franco, one cannot help but wonder what more there is to say.

But history does not work that way. Historians and biographers extract from the past infinite lessons, not just from new sources—which always appear—or from new approaches. They also write for their own historical moment. Today, the rise of dictators during the 1930s and 1940s is calling our attention once again, with the promise of an explanation that might help us make sense of our current predicament. Do countries have the leaders they deserve? The ones they ask for? Or do dictators simply force their way onto the stage through vile talent, exploiting a distracted or disaffected public? As one scholar once said about biographies of Mussolini, one can describe the Duce’s rise in two ways: either he was an exemplar of his age, or he was just lucky.

It is into this breach that Giles Tremlett’s new biography of Francisco Franco leaps. What do we learn from it? The subject is certainly challenging. Franco’s gift as a leader was to remain isolated, keep his own counsel, and use enigma as a tool. Most Franco biographers present a figure who cared little for external assessments. Even close confidants did not often feel they truly had his ear. Infamous for delivering rambling, chaotic, and disconnected rants in public and private, he chronically avoided taking positions—especially in moments where action was demanded, or he felt put under pressure by those around him. In July 1936, he dithered so much before joining the military coup against the Republic that his comrades began referring to him as “Miss Canary Islands.” The sexist sobriquet was the product of their frustration: Franco seemingly required what Tremlett calls “intense wooing” to help overthrow a government of which he had been deeply critical.

Most efforts to sum up Franco have focused on his contradictions, his ability to sow confusion, his obfuscation, and his ideological opacity. He combined a rabid form of anti-communism with a consistent antisemitism that sometimes veered into philo-sephardism. Adding to the mix was an idiosyncratic, almost fanatical hatred of freemasonry, a villain whose contours are curiously hard to make out.

Franco skillfully controlled and manipulated a collection of right-wing parties—a coalition that Tremlett anachronistically calls “far right,” and among which he presumes more unity than there was—that included Spain’s fascist party. But the Falange had to add “traditionalist” to its name to fit into the Francoist coalition, much to the consternation of the various “new men and women” who saw fascism as a break with all traditions.

During the thirty-six years that Franco ruled Spain after declaring victory in 1939, he continued to defy categorization ideologically, psychologically, and diplomatically. Because he kept the motives and core values driving his behavior inscrutable to analysts and the general public, Franco was unpredictable for political opponents and supporters alike. Ruthless and greedy, he was widely reviled and ostracized. Yet all his biographers agree that when it came to decision-making, he cared very little about the hatred he might incite. Perhaps the lesson is that a dictator’s true source of power is his shamelessness. Tremlett agrees with Paul Preston and others that what defined Franco at his core was the arrogant conviction he and only he could lead the childlike Spaniards into the future.

Tremlett’s efficient biography guides the reader quickly through the contexts of Francoist and post-Franco politics, corruption, regionalism, and terrorism. The result, however, is a portrait like others. Franco’s early life, with a distant, philandering father, a devout mother, a more famous brother, an unenviable stature, and a nasally voice, led to a military career of unconstrained violence and dehumanization of the enemy in his colonial experiences in Africa. Combined, these experiences instilled in Franco a basic sense that cruelty was a political act—in fact, the only truly effective one. His legacy was to believe that politics was a ruthless battle. Beating the enemy required brutality and viciousness as both a tool and an example.

In light of Tremlett’s earlier work, which includes the extraordinary The Ghosts of Spain (2006), it is surprising how little he says in this book about Franco’s lasting effects on Spanish society, including its culture, art, and media. Still, his most interesting contribution to our understanding of Franco is his epilogue, which juxtaposes the dictator’s funeral in 1975 with his disinterment from the Basilica at the Valley of the Fallen in 2019. By buttressing the post-Franco period with these two events, Tremlett offers the kind of thought-provoking lesson on Franco and his legacy that the rest of the 404-page biography shies away from. The book’s final line could be a good opening sentence for the book one craves in the current moment: “For those seeking excuses for autocracy or tyranny, Francisco Franco will always provide a role model.”

Joshua Goode is the Book Review Editor of The Volunteer. He is a Professor of History and Cultural Studies at Claremont Graduate University in Claremont, California. His own attempt at a biography of Franco appears in Europe Since 1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of War and Reconstruction, edited by Jay Winter and John Merriman (2006).