Art as Weapon: Wifredo Lam in MoMA Retrospective

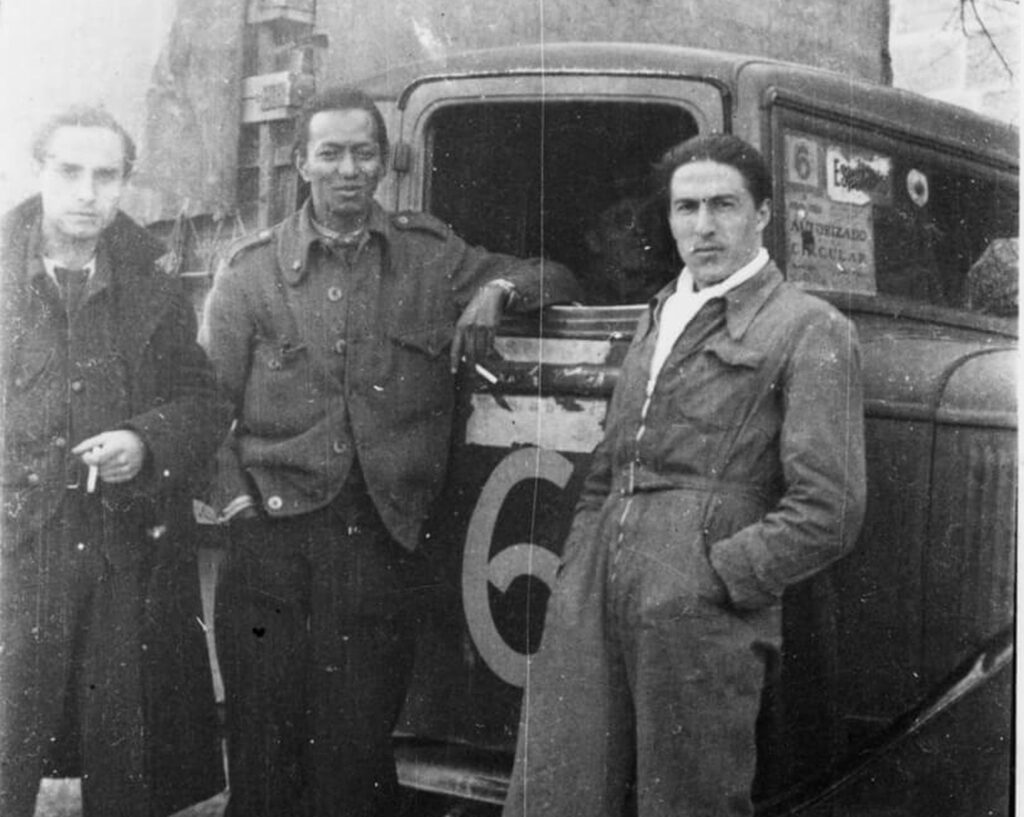

The painter Wifredo Lam (1902-1982), whose work is on display in a long-overdue MoMA retrospective, spent his formative years in Spain—where in 1936 he joined the defense of the Second Republic.

In 1945, when New York’s Museum of Modern Art purchased The Jungle (1943), Wilfredo Lam’s first major painting to explore Afro-Cuban belief systems, the curators inexplicably chose to display it in the museum lobby, next to the coat check. In a way, MoMA’s stunning retrospective of the African-Chinese-Cuban painter, on display until April 11, makes amends for that decades-long slight. Curated by Beverly Adams, the exhibit offers a rare opportunity to appreciate Lam’s magnificently transcultural version of modernism.

Born in 1902 to a Chinese father and a Congolese-Spanish mother in Sagua la Grande on Cuba’s north coast, Lam moved to Spain in 1923 to study artistic technique. He’d live in Europe until 1941, when the rise of fascism drove him back to Cuba, where he re-established contact with his cultural roots. He worked closely with Lydia Cabrera, an ethnologist of Afro-Cuban culture, and illustrated texts by Martinican decolonial theorists Aimé Césaire and Édouard Glissant. Forced to leave by Batista’s military coup in 1952, he spent the years following moving between Europe (mainly Paris and Italy) and the Americas.

Yet it was Republican Spain, where Lam frequented left-wing circles and read Marxist literature, which first politicized the painter. Lam rejected the Eurocentric primitivism of much modernist art, which he denounced for commodifying non-European cultures as objects of curiosity. In Lam’s paintings, Afro-Cuban culture speaks back. Toward the end of his life, he described his work as “an act of decolonization.”

Lam initially made no connection between his artistic aspirations and his ethnically diverse background. (Lam’s godmother was a respected Lucumi priestess; we know less about his Chinese cultural heritage.) In the 1920s, however, he discovered prehistoric and African art at Madrid’s Archeological Museum. In 1933, also in Madrid, he met the Paris-based Cuban writer Alejo Carpentier, who had gone into exile from the Machado regime in Cuba and who that year published his first novel, Ecué-Yamba-O, a pioneering exploration of Afro-Cuban culture.

After the military uprising against the Spanish Republic in July 1936, Lam joined the Fifth Regiment, the informal name given to the Communist Party’s militarized unit—also known as the “Talent Battalion” because it attracted many writers and artists. He designed several posters for the Republican Propaganda Ministry, none of which seem to have survived. Information about his participation in the defense of Madrid against Franco’s November 1936 assault is vague. From October 1936 to March 1937, he worked in a munitions factory, where he supervised the manufacture of anti-tank bombs. After contracting chemical poisoning, he was sent to a sanatorium at Caldes de Montbui, north of Barcelona. On the way, in Valencia, he met the sculptor Timoteo Pérez Rubio, who happened to chair the committee selecting artworks for the Republic’s Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris World’s Fair. Pérez Rubio encouraged Lam to submit a painting. The result—which Lam did not complete in time for the Paris exhibition—was The Civil War, the first painting to feature his distinctive style.

Painted in blues and grays with strong black brush strokes on wrapping paper (he couldn’t afford canvas), and measuring just under 7 x 8 feet, La Guerra Civil depicts a jumble of suffering bodies compressed into a contorted mass by a tank advancing from the top right, with a civil guard’s three-cornered hat visible in the top left. Arms are prominent; two of them brandish a sickle and a red flag. Faces are mask-like. Like Picasso’s Guernica, painted for the same Paris exhibition, the painting is hard to decipher but is a clear depiction of pain.

In May 1938, Lam left Spain for Paris, where Picasso took him under his wing, and where he painted Douleur de l’Espagne (The Sorrow of Spain), with two geometric female figures crossing their hands over their chest and face respectively. The one visible face is a mask. This is the only other painting by Lam that references the Spanish war.

Still, the conflict left a lasting impact on his work. In a later interview, Lam stated that his experience of the war in Spain turned his art into a weapon. In 1981, a year before his death in Paris, the Cuban government awarded him the Internationalist Combatant Medal for his participation in the defense of the Spanish Republic.

Jo Labanyi is Professor Emerita of Spanish at New York University. MoMA’s retrospective “Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream” continues through April 11, 2026.