Paul Robeson’s Antifascist Lessons

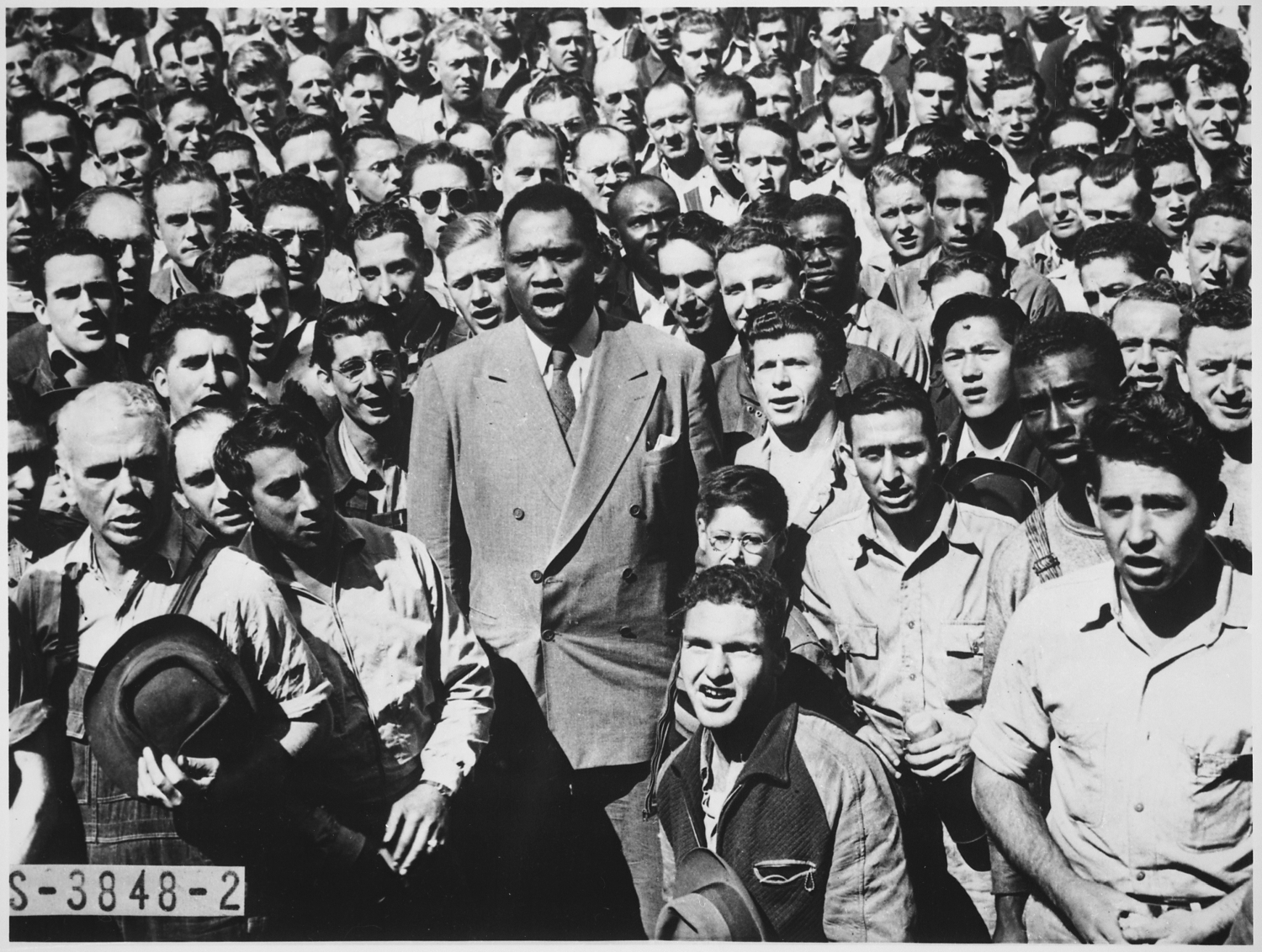

Robeson leading Moore Shipyard workers (Oakland) in the national anthem, Sept. 1942. NARA, Public Domain.

The climate of the Cold War was anti-radical—but it was also white supremacist, as Paul Robeson experienced firsthand. Yet it didn’t faze him, Lindsey Swindall explains. “He not only refused to stop speaking against militarism, segregation, and colonialism, but found new ways to disseminate his message.”

As the Second World War concluded in 1945, artist and activist Paul Robeson was wrapping up a record-breaking run in Shakespeare’s Othello that had started on Broadway and then toured the United States and Canada. The prospect of peace filled him with optimism. “This can be the final war,” he wrote in The American Scholar. “It is possible to solve once and for all the problem of human poverty, to attain a speedy freedom and equality for all peoples.” Along with many progressives, civil rights activists and others who had supported the war effort, Robeson’s expectation was that, once fascism was defeated abroad, the United States would turn to dismantling its manifestations at home—including racial segregation and support for colonial empires.

But it was not to be. Rather than an era of peace and progress, the end of the war gave way to militarism and repression. There were immigration crackdowns. Passports were revoked, loyalty oaths imposed. And anything less than unquestioning fealty to the State was considered subversive, disloyal and dangerous. The climate of the Cold War was anti-radical, to be sure. But it was also white supremacist.

Robeson experienced those deeply troubling developments first-hand. He supported the 1948 Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry A. Wallace, who emphasized peace, diplomacy, and ending segregation—but that campaign was met with a stunning defeat. Following some off-the-cuff remarks at a World Peace Conference in Paris in 1949, where Robeson highlighted the need to end global militarism and systems of racial oppression, the mainstream US press turned virulently against him. Some Robeson concerts were canceled. Worse, concert attendees in Peekskill, New York were assaulted by vigilantes. Then, in 1950, the State Department revoked Robeson’s passport, claiming that his outspokenness undermined the US interests. While in 1945 Robeson’s career had reached an artistic pinnacle, just five years later he was trailed by the FBI, his income was plummeting, and he was treated as a pariah across the nation.

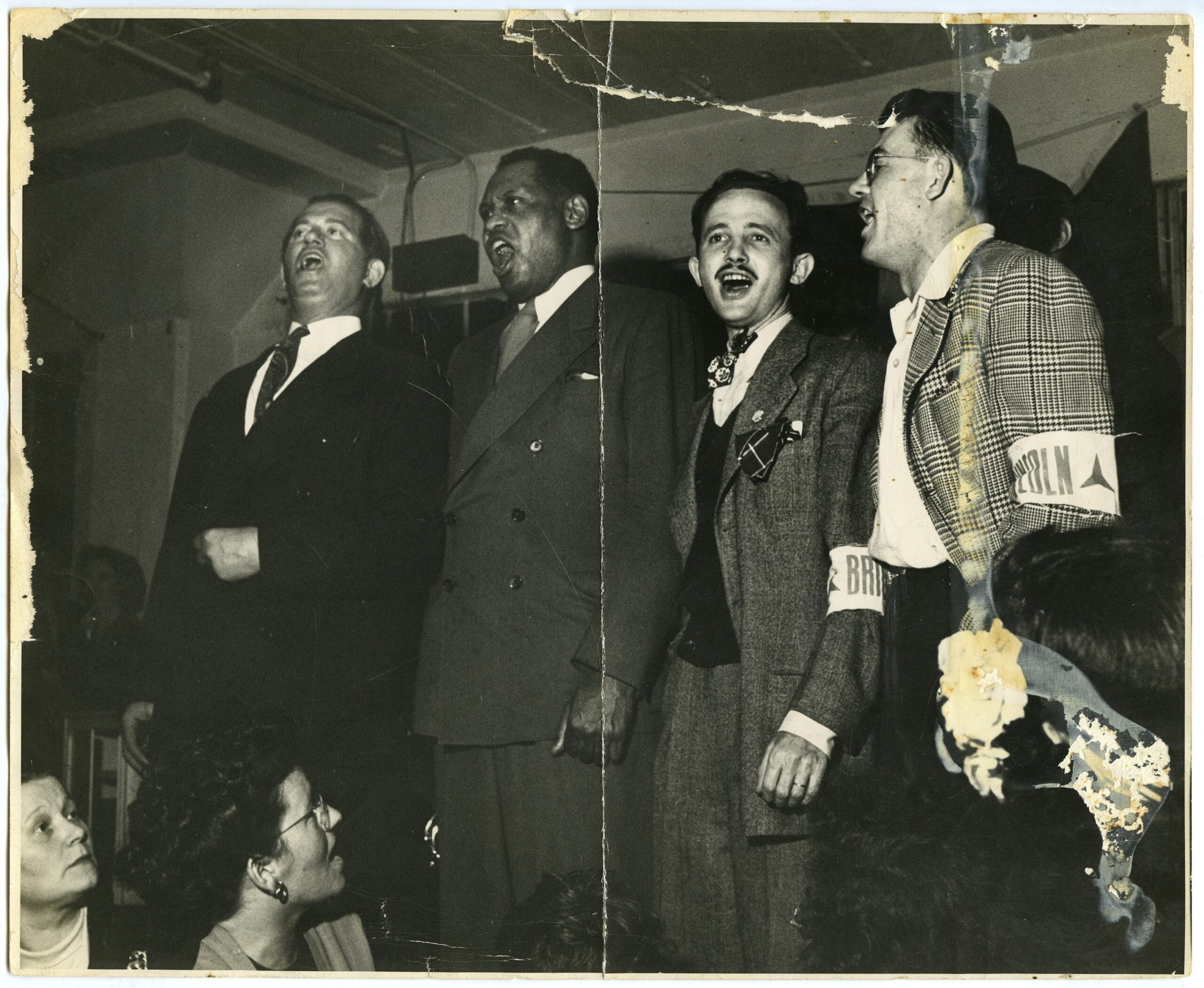

Bart van der Schelling, Paul Robeson, Moe Fishman, and Art Landis. Tamiment Library, NYU, ALBA Photo 66, box 1, folder 3.

Today, as we face yet another rise of a vindictive, power-hungry right-wing movement, looking to the past can be instructive. Reading today about the courage of Robeson and those like him reminds us of their commitment in the face of authoritarian tactics. The anti-fascism of the post-WWII era holds important lessons for us—including the importance of solidarity, unity, and resiliency.

In his statements following the Peekskill riots, Robeson compared the attackers to “Hitler’s storm troopers” who struck at “all who stand for peace and democracy in America.” In response, Robeson and others quickly organized another concert in Peekskill, followed by a six-city concert tour, as acts of solidarity and peaceful protest. Such opportunities to come together peacefully and uplift each other were sorely needed.

When Robeson’s passport was revoked, he missed out on artistic work around the world. He wasn’t even allowed to travel to Canada. In response, a concert was organized in May 1952 at Peace Arch Park in Washington State, on the US-Canadian border, where tens of thousands gathered to demonstrate their solidarity. Hearing Robeson’s voice travel across the border, when his body could not, buoyed the spirits of people who supported free speech, civil rights, and anti-colonial struggles. When he returned in 1953 to sing at the border again, Robeson repeated a message he often stressed during those years: “I know that there is one humanity, that there is no basic difference of race or color … [and] that all human beings can live in friendship and in peace.” Robeson did not just talk about a vision of living in peace and friendship, but put it into practice at his concerts, if only for a few hours.

The response to Peekskill and the Peace Arch concerts illustrate the resilience of US anti-fascists in the postwar years. Robeson not only refused to stop speaking against militarism, segregation, and colonialism, but found new ways to disseminate his message—even when mainstream media largely ignored or maligned him. Starting his own newspaper, Freedom, allowed Robeson to create a space for news, history, and culture that placed people of African descent at the center of the story. Freedom engaged stalwarts like W.E.B. Du Bois, Louise Thompson Patterson, Eslanda Robeson and W. Alphaeus Hunton while also nurturing the talents of younger writers and activists like Louis Burnham, Esther Jackson, and Lorraine Hansberry. When mainstream presses refused to publish Robeson’s memoir, he founded his own company to distribute his book, Here I Stand, and recordings of his music. When one of the founders of the Council on African Affairs abruptly turned rightward, Robeson and others took over the reins and doggedly continued the anti-colonial work of the organization.

Few moments illustrate Robeson’s resilience better than his testimony before the infamous House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956. Although he had to testify before the committee shortly after undergoing a difficult surgery, Robeson stood firm. HUAC, known for ferreting out radicals, also had long-time segregationists among its members. When the committee confronted Robeson with his famous statement that it was in Russia where he had first felt “like a full human being,” because of the lack of racial prejudice, and asked him why he hadn’t moved there, Robeson’s reply was unwavering in its antifascism: “Because my father was a slave, and my people died to build this country, and I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it. Is that clear?”

Perhaps Robeson’s most significant lesson for us today is that, while periods of repression are damaging, they do end. Robeson’s resilience paid off when his passport was restored in 1958. Before going on a triumphant, extended global concert tour, Robeson performed to a sold-out crowd at Carnegie Hall, signaling that major concert halls were again welcoming him. By bringing people together and by resiliently continuing his advocacy, Robeson helped push the anti-fascist fight forward and cleared the way for the next generations of antifascists.

Lindsey Swindall teaches at Stevens Institute of Technology. She is the author of The Politics of Paul Robeson’s Othello, Paul Robeson: A Life of Activism and Art and The Path to the Greater, Freer, Truer World: Southern Civil Rights and Anticolonialism, 1937-1955.