Of Gargoyles and Guttersnipes: How City College Stood Up to Fascism in 1934

Antifascism has long been synonymous with American values. In 1934, student activists at New York’s City College arguably understood this better than many do today.

As jeers and cat calls erupted from the student section, the restive Great Hall at New York’s City College (CCNY) filled with the din of two thousand murmuring voices. “Guttersnipes, your conduct is worse than that of guttersnipes,” muttered College President Frederick B. Robinson, visibly upset. It was October 9, 1934—and a new epithet was born.

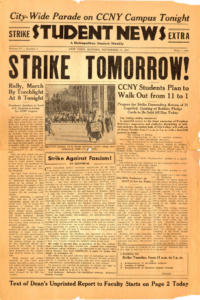

The CCNY community had gathered to welcome a small group of Italian students who were visiting American universities as part of a goodwill tour from Mussolini’s Italy. This cultural exchange, chronicled by Robert Cohen in When the Old Left Was Young, was fiercely opposed by campus groups worried the Italian visitors would promote fascist propaganda in Shepard Hall, the gargoyle- and grotesque-covered building that was the symbolic heart of CCNY’s iconic campus. Warnings and calls for resistance filled college newspapers and pamphlets ahead of the event.

Fearful of disruption, President Robinson had warned students against making overt political statements during the assembly or engaging in any behavior that might tarnish the reputation of the institution. They ignored him. “I do not intend to be discourteous to our guests,” Edwin Alexander, who represented the student council, said in his formal address to the visitors. “I merely wish to bring them anti-fascist greetings from the student body of City College to the tricked, enslaved student body of Italy.” These would be Alexander’s last words at the podium, as administrators dragged him away from the microphone. Handwritten notes on the back of a political poster preserved in CCNY’s archive described the scene that followed. As some of Alexander’s supporters rushed the stage to help him, “fists flew freely,” and partisan pushing and shoving plunged the Great Hall into chaos.

The tense exchange mirrored the international scene during the interwar period, as individual citizens and their local governments responded in different ways to the rise of right-wing authoritarianism. Remarkably, CCNY students were ahead of the university leadership in defending their alma mater’s institutional integrity. Using publicity and direct action—through their school newspaper, The Campus, protests, and mass demonstrations—student activists were able to clearly articulate the threat that fascism posed to democracy and to American values.

Such values, of course, included freedom of speech and of assembly as well as academic freedom more broadly. Both had come under assault during the interwar era, an age of radical campus activism across the country. A backdrop to college life in the decades following the devastating war 1914-18 was the tension between national loyalty and free speech, perhaps best articulated by the Supreme Court’s 1919 decision to label anti-government agitators as a “clear and present danger,” allowing the government to restrict first-amendment protections if warranted by national security. The debate on national loyalty and first-amendment rights returned to college campus debates following Hitler’s 1933 ascension to the German Chancellery—but this time it was accompanied by a new concept: antifascism.

The term first entered the American lexicon thanks to Willi Münzenberg, who brilliantly exposed the injustice of the German trial following the Reichstag Fire through a widely publicized counter trial in London. The antifascism that Münzenberg represented, with its implied defense of democratic principles and the promise of direct action against fascism, gave new legitimacy to student activism across the democratic West, the United States included. Crucially, it reconciled students’ desires to be patriotic, principled, and academically committed.

The emergence of antifascism coincided with a larger debate about “Americanism” that began in the early 1930s (when the phrase “The American Dream” was coined) and was especially prominent on college campuses. It was not long before Congress joined the conversation. In December 1933, the House of Representatives instituted the McCormick-Dickstein Committee to combat, wherever possible, “the overthrow of democratic principles and personal liberties; the freedom of the press, liberty of speech, rights of franchise without discrimination as to race, creed, or color…” Urging Americans to be vigilant against “those dark forces that are working against us,” the Committee’s work sought to define what constituted “American” values and behavior. It was in this context that American anti-fascism first emerged. It was defined on an ad-hoc basis by an active public that embraced it as a moral argument against “un-American” behavior.

The arrival of the Italian delegation in October 1934 foregrounded the national debate on fascism and the dangers it might pose for American civil society. Days before the visit, The Campus, the CCNY paper, ran a story with the headline: “Fascist Group to Visit Here on School Tour.” The piece called attention to the reaction of other regional universities to visits from the Italian delegations. Mentioning the opposition of the Yale chapter of the National Student League, a Communist-led radical student organization founded in 1931, the piece quoted from the NSL’s formal protest to Yale President Angell: “the Italian students represent the destruction of intellectual integrity characteristic of fascism.” The Campus story, in other words, not only portrayed the City College campus as a site of intellectual and democratic ideals to be protected from fascism but also as part of a national academic community.

The next issue of The Campus advertised a protest in the campus quad in a story titled: “Student Council, Radicals Plan Flagpole Protest Against Visit of Fascists.” In addition to once again denouncing fascism, the story related that “many groups” planned to protest at the demonstration, acknowledging the power of anti-fascism to unite groups across the political spectrum. The article also noted that many students now held Robinson himself in suspicion for extending official greetings to the Italians in the first place. One upperclassman even charged the President with “acting against the interests of the student body for the sake of a decoration from the Italian government.” “We must oust Robinson, the Fascist president of the College,” he stated. A contemporary political poster made these points even more explicit. Student strikes would be ineffective, it stated, if they did not “raise concretely a militant protest against the fascist tendencies of our administration as exemplified by President Robinson.” These claims—fairly or unfairly—painted Robinson as a defender of the same “dark forces” that were increasingly working against the freedoms outlined by the House Committee.

Students feared the official welcome would lend credibility to Mussolini’s regime. They saw the “visit of the Italian Black shirts (as) an attempt to reestablish Mussolini’s reputation and popularize fascism here.” They presciently worked to stop this popularization by dominating all possible mediums of publicity. Defending academic freedom and free speech gave CCNY students—neither “tricked” nor “enslaved”—noble causes to rally around. Yet the embrace of antifascism gave the students something to do in a moment when fascism came to the very gates of the College. Their physical and discursive opposition to the Italians created a public firestorm resulting eventually in the suspension and expulsion of dozens of students—but also in a significant contribution to the national conversation about national loyalty, which now proposed antifascism as both a logical goal of patriotic activism and one soon to be sanctioned by the federal government.

Indeed, an “antifascist philosophy” emerges from the conclusions of the McCormick-Dickstein Committee’s work in February 1935. In a nod to the importance of maintaining a public sphere free from “dangerous” foreign influence, the Committee included in its recommendations that Congress should enact a statute requiring all “publicity, propaganda, or public-relations agents” of foreign governments or political parties to register with the Secretary of State of the United States. The committee further stated:

To the true and real American, communism, naziism (sic), and fascism are all equally dangerous, equally alien and equally unacceptable to American institutions . . . Whatever may be the result elsewhere, the constitutional rights and liberties of American citizens must be preserved from communism, fascism, and naziism. The only ‘ism’ in this country should be ‘Americanism.’

For CCNY students in the Fall semester of 1934, Americanism was synonymous with antifascism. The extent to which antifascist activists at CCNY galvanized students from across the political spectrum would be made patently clear in 1936-37, when a contingent of more than 40 CCNY students volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War.

By presenting themselves as the ultimate defenders of college policy and institutional reputation, antifascist students won nation-wide credibility when their efforts coincided with the objectives of the National Government. But this credibility would not last forever. On their return from Spain, the volunteers would be branded “Premature Anti-fascist” and investigated for potential ties to Communism by the very congressional committee mentioned above—now known as the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Yet for a brief, important moment, student activists succeeded in making antifascism synonymous with Americanism and democracy. The CCNY incident shows an example of civil society defining “American” behavior for itself, and declaring it to be democratic, loyal to liberal institutions, and antifascist. Ironically, President Robinson was himself instrumental in creating a new category of antifascist identity when coining a nickname many students would later embrace. In subsequent rallies and around the CCNY campus, activists proudly wore buttons claiming: “I am a Guttersnipe. I fight Fascism.”

Carter Barnwell is a graduate of The City College of New York and holds a doctorate in Modern European History from the University of New Mexico. This story is based on research funded by the UNM’s Latin American and Iberian Institute in Albuquerque, New Mexico.