Miguel G. Morales: “If You Look at an Image Carefully Enough, It Will Start Emitting Its Own Light.”

For Miguel G. Morales, the archive is an endless treasure trove. His new short on Cuban volunteers in the Spanish war brings it to life. Next up: a feature-length project on the Lincoln Brigade.

More than a thousand Cubans—one of the highest per-capita contributions in the world—joined the International Brigades to defend the Spanish Republic. On November 21, Espacios de Cultura (NYU) will screen Listen to the Shadow (Escuchar la Sombra), a compelling short film by Spanish independent filmmaker Miguel G. Morales, who uses historical photographs and archival footage to create a moving tribute to the Cuban volunteers.

Morales, who was born in 1978 in Tenerife (Canary Islands), has a special bond with Cuba. His paternal grandfather was born in Havana as a child of Spanish migrants. After moving back to Tenerife in the 1920s, in 1936 he was forcibly recruited, totally against his will, along with many other Canarios, to fight in the army of Franco—who at the time of the coup was stationed on the islands.

Morales himself spent significant time in Cuba as well: he studied there in the late ‘90s (Escuela de cine de San Antonio de los Baños), and he returned a couple of years ago in search of rare archival materials. This fall, he spent some months in New York working on a new feature-length project on the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and the relationship of the city with the Spanish Second Republic.

Tell me about the new project. When you begin working on a film like this, do you know what the finished product will look like?

No, I don’t. But I do have a sense of its rhythm and cadence. Just like my short on the Cubans, this new film will be a story at street level, focusing on the experiences of everyone who was an outsider at the time: women, ethnic minorities, and activists. I also know that the movie will incorporate the search process itself—a process often shaped by chance. Let me give you an example. I accidentally came across a text by Langston Hughes in which he writes that, when he entered Spain during the war on a train together with Nicolás Guillén, he realized that he and Guillén were the only Black people on board. Then, at one stop, a mulatto joins them. When they go talk with him, he tells them he is a Canary Island fisherman who’s fled from the Nationalists with his boat and traveled all the way through Africa to Spain to fight for the Republic. Reading that story moved me deeply. In a way, it’s a metaphor of my own journey: two Black men, one from the United States and the other from Cuba, who are entering Spain clandestinely—and then run into someone from Canarias!

How did you come up with the idea for the Cuban film?

Totally by chance as well. When I was in Cuba to present a fiction short of mine, for some reason I came across a speech that Pasionaria gave in Cuba in 1963, in which she remembers the Cuban volunteers who came to Spain. Once I decided to make a movie about them, I made sure to get a Cuban script writer—the great Atilio Caballero—and Fajardo, a Canarian composer, for the soundtrack to avoid any hint of cultural appropriation. But even then, chance played a huge role. It was chance that allowed us to discover that the great Belkis Vega had made a documentary about the Cuban volunteers in 1983 —when she was only 31 years old—titled España en el corazón, which includes interviews with veterans. That film had been so totally erased from Cuba’s cultural memory that we had to go to the Cinemateque of Catalonia to find a copy.

About “Listen to the Shadow” you write that it is a “song to the memory of the so-called defeated, who were in fact never defeated, to those who sacrificed themselves and their bodies for a better world. … It is also a film that seeks to come to the defense of everyone who was left out of the official history of the legendary International Brigades …, to weave alternative paths through history.” Can you tell me about your process?

I think of myself as a visual artist who does research in the archive. Sometimes that research results in a movie, sometimes in an installation, and sometimes in something else altogether. More than as a creator, I prefer to see myself as a catalyst of the archive. The documentary movies I make are personal essays in which I go in search of stories that are hidden in the archive but have never been told. Mind you, I don’t claim to be doing history or biography. I am interested in the image and how it interpellates me. When I do research, I like to let myself be sidetracked, guided by chance, to go down roundabout paths that I couldn’t have imagined in advance. For example, I only realized later that, for me personally, making the film was a way to repair the horrible dilemma that my Cuban grandfather faced when he was forced to fight for Franco.

Your Cuban movie seems like a declaration of love for the images themselves—a love that makes you want to rescue them, resuscitate them, bring them back into circulation. Or perhaps to make us look differently at images we thought we knew.

It’s true that I have a very special relationship with images. They saved me when I was going through a very traumatic time in my childhood. Simone Weil said somewhere that the desire for light ends up producing light. In other words, if you look at an image carefully enough, it will start emitting its own light. It’s always important to go beyond the first impression. Right now, for example, I am in the archive all day looking at thousands of images. Every now and then, one will jump out at me. For me, those moments are crucial. What is it about that one image that makes me stop and look again?

The Cuban film opens with images of women volunteers.

Yes, because we wanted to normalize the presence of women in the war. Have you noticed that almost all the films about the Civil War limit themselves to a single sequence about the role of women? We wanted to go against that trend. For that same reason, we tried to avoid images of casualties, trenches, bombs, and airplanes. Emilio Silva, the founder of Spain’s Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory, loved that we did not put images of violence front and center. “After all,” he said, “the fascists have always used images of violence against us.”

Although the 1930s produced fewer images—moving or still—than we do today, there are still thousands of photographs and hours of film to choose from. How do you decide what makes the cut?

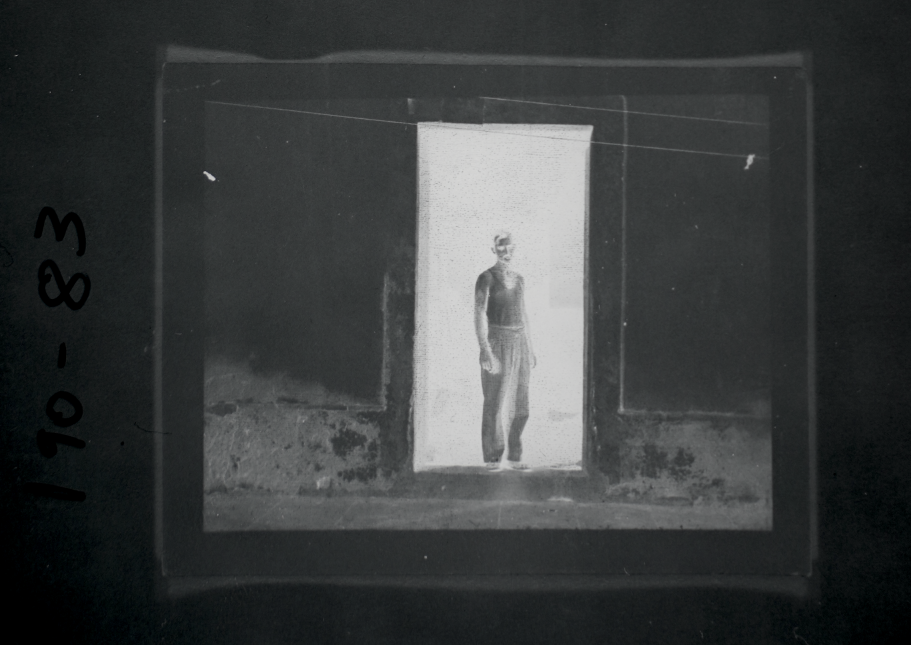

I always try to decontextualize the archive. That often means working with raw materials, including negatives and outtakes. This is also why I couldn’t do this work without the generous help of people like Shannon O’Neil, the curator at the Tamiment Library. For this film, I had access to Harry Randall’s negatives (Randall was the Chief Photographer of the Photographic Unit of the XV International Brigade, ed.), which included images he chose not to print. Going through the negatives, you can tell what his eye was drawn to—details of the soldiers’ daily lives, for example.

Your film makes a point of showing us that we are looking at images from an archive. You often show them as negatives, as microfilm, or held down by thumb and index finger.

The point, for me, is precisely that I am manipulating the archive. I am looking at it from my present moment, and my gaze contributes to the meaning of the image—as does the gaze of the people who view the film.

Manipulating images to create a new meaning was also what drove montage artists from the 1920s and ‘30s, like Josep Renau, John Heartfield, Kati Horna, or Luis Buñuel, who helped create some of the most iconic images of the Spanish war. To what extent is your editing process—your montage—deliberate, and how much do you leave to chance?

I try to do both. Just as I do with my research process, in the editing process I try to remain open to randomness—an unexpectedly powerful combination of images, for example, or image and sound. But then, at a later stage, I become obsessive and perfectionist about the emotional rhythm of the film, which is absolutely crucial in all my work. For Escuchar la sombra, the writer, the composer, and I worked together throughout the editing process so that the images, the text, and the music bled into each other organically, just as the three of us bled into each other. None of us had any idea of where we’d end up.

Join us for the screening on November 21. More information, including an RSVP link, here.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin.