Kirsten Weld: “The Administration Has Made No Secret of Its Admiration for Franco-Style Authoritarianism.”

Kirsten Weld has spent years studying Latin American dictatorships and the citizens who fight to hold them accountable. That experience has proven valuable in her current role as president of the AAUP chapter at Harvard, which, in March, sued the federal government for targeting students and faculty—and won.

President Trump has “a problem … with the First Amendment”, William G. Young, a senior U.S. district judge, wrote in September, adding: “The President’s palpable misunderstanding that the government simply cannot seek retribution for speech he disdains poses a great threat to Americans’ freedom of speech.”

This striking passage is part of the scathing 160-page sentence following a suit brought in Massachusetts against four defendants—the President, the director of ICE, and the Secretaries of State and Homeland Security—by the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), the Middle East Studies Association, and AAUP’s Harvard, Rutgers, and NYU chapters. The plaintiffs claimed that the administration had violated the first-amendment rights of students and faculty when it targeted non-citizen university affiliates for deportation as retribution for their pro-Palestine activism.

The outcome of the AAUP v. Rubio case has been one of the most decisive judicial blows dealt to the administration so far, both in the evidence that the proceedings brought to light and in the court’s unequivocal assessment of the administration’s goals, intent, and methods. At the end of his ruling, Judge Young, who is 85, quotes Ronald Reagan, who appointed him: “Freedom is a fragile thing [that] must be fought for … by each generation”.

“As I’ve read and re-read the record in this case,” Young adds,

… I’ve come to believe that President Trump truly understands and appreciates the full import of President Reagan’s inspiring message—yet I fear he has drawn from it a darker, more cynical message. I fear President Trump believes the American people are so divided that today they will not stand up, fight for, and defend our most precious constitutional values so long as they are lulled into thinking their own personal interests are not affected. Is he correct?

Kirsten Weld (Ottawa, 1982), a Professor of Latin American History and the President of the AAUP chapter at Harvard, would like to answer that question with a resounding “no.” But she’s not sure. “In the face of the attacks on higher education from the administration,” she said when we spoke in October, “it’s been painful to see the relative absence of a collective response. As an historian who has worked on authoritarian regimes, I know that is a common reaction. On the other hand, my work with the AAUP this past year has also shown me that everyone can do something, however small, and that you never know what effects those small actions might have. We saw that in the court case. When we first brought the suit back in March, we had no idea it was going to go this far. Our only thought was: “The government is going after our students and colleagues. We must do something!” As it happened, the same evening we filed the paperwork, ICE abducted Rümeysa Öztürk, right in my neighborhood, for having co-authored an op-ed in her Tufts college newspaper. In that moment, that felt like such a defeat. Fortunately, we were able to add her and subsequent arrests to the case as it developed.”

Kirsten Weld (Ottawa, 1982), a Professor of Latin American History and the President of the AAUP chapter at Harvard, would like to answer that question with a resounding “no.” But she’s not sure. “In the face of the attacks on higher education from the administration,” she said when we spoke in October, “it’s been painful to see the relative absence of a collective response. As an historian who has worked on authoritarian regimes, I know that is a common reaction. On the other hand, my work with the AAUP this past year has also shown me that everyone can do something, however small, and that you never know what effects those small actions might have. We saw that in the court case. When we first brought the suit back in March, we had no idea it was going to go this far. Our only thought was: “The government is going after our students and colleagues. We must do something!” As it happened, the same evening we filed the paperwork, ICE abducted Rümeysa Öztürk, right in my neighborhood, for having co-authored an op-ed in her Tufts college newspaper. In that moment, that felt like such a defeat. Fortunately, we were able to add her and subsequent arrests to the case as it developed.”

The AAUP was founded in 1915. Did it really take more than a hundred years to create a Harvard chapter?

(Laughs.) No, there have been chapters before. The most active period was in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when Sen. Joseph McCarthy and others claimed Harvard had been overrun by lunatic Communists who wanted to destroy the fabric of America. The almost literal echoes with the rhetoric coming from the administration today are striking.

What do those echoes tell you?

The fact that every generation seems to have to fight the same battle could be a depressing insight. But I found it oddly reassuring to see that the current administration is simply tapping into a well-established vein of anti-intellectualism: a kind of pseudo anti-elite posturing by people who themselves are the product of these same elite institutions.

Are there any tactical lessons to draw from those past battles?

Yes, although they are not surprising. They involve solidarity, collective action, and not allowing individual people and institutions to be picked off through cooptation. These may be principles rather than tactics, but you can’t have one without the other.

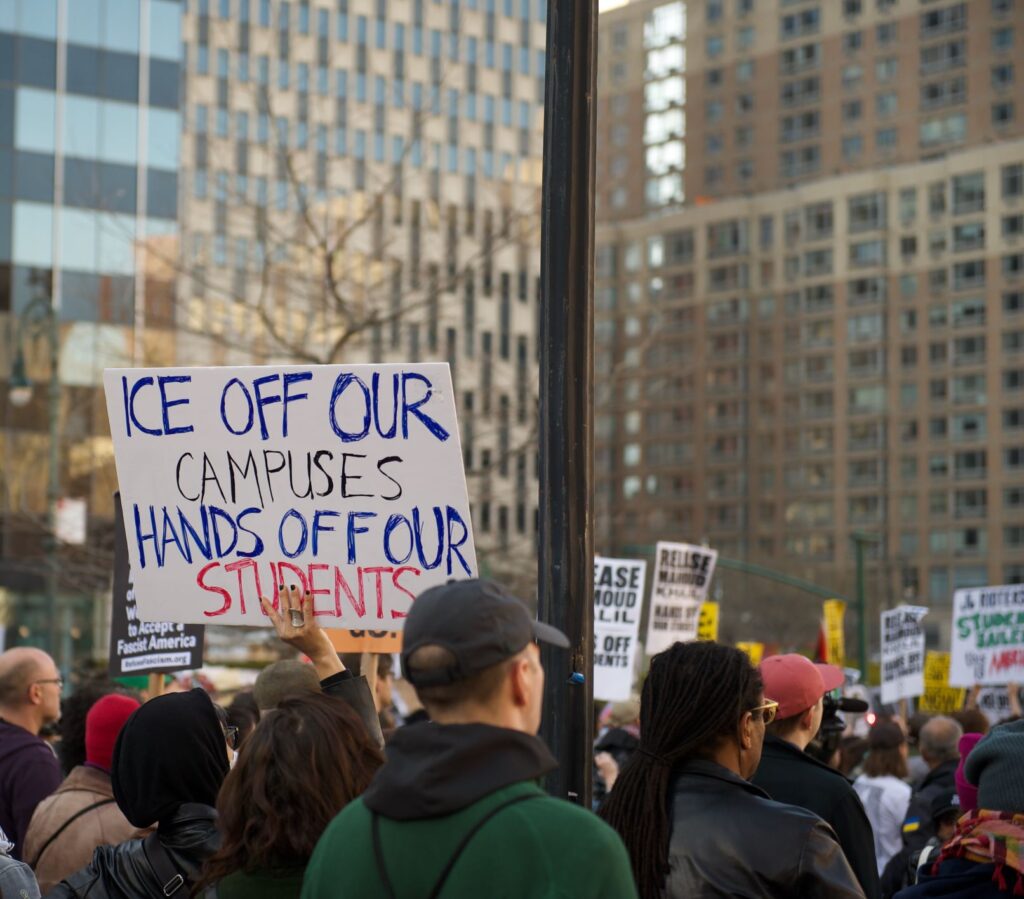

Protests in NYC against the detention of Palestinian activist and Columbia student Mahmoud Khalil, 10 March 2025. Photo SWinxy. Wikimedia Commons.

What prompted you to resuscitate the AAUP chapter at Harvard?

A long-brewing governance crisis; we don’t even have a faculty senate, though efforts are underway to create one for the first time. In recent years, the faculty has been increasingly marginalized. After Harvard was thrust into the national spotlight following October 7, 2023, the Harvard Corporation, which is our equivalent of a board of trustees, went repeatedly over the heads of the faculty. That created a huge amount of discontent.

At many public universities, the AAUP functions as a labor union. At Harvard and other private colleges, it has what are called “advocacy chapters.” These also operate on the principles of solidarity and collective action. But what does that look like, given how massively different academic working conditions are across the country?

That’s a good question. I’ve been in AAUP workshops with colleagues at colleges in Texas, for example, where the state legislature has an enormous amount of direct power. Faculty there are afraid not just to join the AAUP but to be associated with colleagues who are—and they are right to!

That kind of fear-induced caution seems to be spreading everywhere, though.

Yes, even here at Harvard I’ve talked with non-tenured or non-citizen colleagues who are afraid to join the AAUP because they fear deportation or professional retaliation. That may sound ridiculous—but it was also ridiculous for Rümeysa Öztürk to be arrested for having co-authored an op-ed in her campus paper. Still, all that said, the circumstances here at Harvard, especially for tenured faculty, are not comparable to those in many other parts of the country.

In the examples you gave, being at a private institution provides some protection from the State. But when it comes to first-amendment protections, you’re actually more vulnerable at a private university. What we’ve seen since January is that the real power of protection comes from civil society: organizations like the AAUP, the ACLU, and labor unions.

I agree. That, too, is a familiar historical pattern, of course. It’s precisely why regimes have long been bent on destroying people’s ability to organize in those forms.

Mark Bray, the Rutgers historian of antifascism who was forced to seek exile in Spain, told me that if it hadn’t been for the fact that he teaches at a New Jersey public university with a strong union, he’d been fired a long time ago.

Rutgers is a great example, given its historical legacy of labor organizing and cross-sector solidarity.

What’s it like at Harvard?

When you’re at an institution that does not have that kind of history, it can be a challenge to get going. When folks don’t default to an understanding of themselves as workers, they may have trouble seeing themselves in meaningful solidarity with other groups of campus workers. Imagining that faculty inhabit a separate category is a luxury that has been cultivated in the private, elite higher-education space.

A luxury that, now, has proven to be a liability. Maybe that’s why the administration first went for the Ivies.

Totally! If they had tried to go after Rutgers first, I doubt they would have come away with an early “deal” like at Columbia. As far as Harvard is concerned, I am pretty sure that if there had not been an AAUP chapter back in March when the university was in backroom negotiations with the federal government trying to do a deal of its own, things would have turned out differently.

How has your experience with the courts this past year shaped your faith in the judiciary?

It’s complicated. On the one hand, the judiciary has served as a crucial check—much more so than, say, Congress, which has totally abdicated its responsibility—upon a regime that seems hell-bent on shredding the rule of law as we know it. On the other hand, you need lawsuits and rulings and judicial relief for that check to function, and the Trump administration’s “flood the zone” approach has made it difficult for the judiciary to keep up with the pace and extent of unlawful and unconstitutional governmental activity.

I’m curious how you read the current moment as an expert on twentieth-century Latin America. Your first book is on the police archives that document the genocidal actions of the military dictatorship in Guatemala. What parallels do you see?

The idea I keep coming back to is that you never know what consequences your actions might have. Keeping a scrap of paper that attests to someone having been in a particular place at a particular time—or, today, recording a video of someone being arrested—may prove crucial in the future to shape a narrative or build a court case. Over the years I have worked with and written about astonishingly brave folks all over the hemisphere who don’t know what outcome their work might have. But they keep doing it anyway, putting one foot in front of the other, even as the landscape looks incredibly bleak. The other day I read about how, in Chicago, people are using free street libraries to distribute whistles along with a simple code to issue warnings when ICE is around. Someone came up with that idea and put it in practice, without knowing if it would work—and now it has empowered people to collectively defend their neighbors and communities from the masked paramilitaries besieging them.

You are currently working on a book about the ways that the Spanish Civil War shaped Latin American politics across the continent during the Cold War. You show how dictatorships in Chile, Guatemala, or Argentina were directly inspired by Francoism. Can’t something similar be said about the US today?

That’s a bit of a leading question! (Laughs.) But yes, I see several parallels. For one, Trump, like Franco, is a kind of idiot savant of coalitional politics. Both have an intuitive grasp of how to get people who disagree with each other on fundamental issues pointed in the same direction. But there are more direct connections as well. Some of the most powerful people in the current administration are recent converts to Catholicism who have made no secret of their admiration for integralist approaches, including Francoism. They are part of a strain in US reactionary thought that looked to Spain for inspiration, not just in the 1930s but through the 1960s and ‘70s. The people behind some of the first big anti-abortion demonstrations in 1970, like L. Brent Bozell and Fritz Wilhelmsen, saw themselves as American Carlists—including the paramilitary methods and the red berets. They wanted to turn the US into a Catholic confessional state. So-called “post-liberals” like J.D. Vance are part of that lineage.

What also reminds me of Francoism is the way they describe anyone who disagrees with them as part of a massive left-wing conspiracy to destroy civilization.

You know, for my book, I’ve forced myself to carefully read a slew of reactionary and Falangist writers. It wasn’t fun, exactly, but it did allow me to understand something that is present quite clearly both in the reactionary Hispanophone space and in Trumpism today.

What did you discover?

The thing that they hate is not actually whatever they think communism is, though they do hate that, too. The thing that they really hate is the Enlightenment, or at least what “the Enlightenment” has become a shorthand for: secularism, modernity, equality, mass politics. They hate liberal universalism – its implicit leveling of what the far-right sees as “natural” racial and gendered and civilizational hierarchies. And they think that communism is bad because it’s a thing that liberalism helps to produce. Therefore, if you want to eradicate communism, what you must destroy is liberalism—the universalist idea that we should tolerate and find ways of coexisting with people with whom we may disagree or who have different faith traditions. For them, that very aspiration is itself a weakness, indeed a pathology, that needs to be extirpated.

Sebastiaan Faber teaches at Oberlin College. A Spanish version of this interview appeared in CTXT: Contexto y Acción.