Book Review: Writers, Outsiders, and the Spanish War

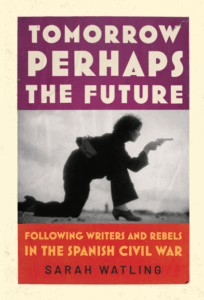

Sarah Watling, Tomorrow Perhaps the Future: Writers, Outsiders, and the Spanish Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023), 372 pp.

Sarah Watling, Tomorrow Perhaps the Future: Writers, Outsiders, and the Spanish Civil War (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2023), 372 pp.

What do you do when you feel like your world is profoundly threatened, but very few people around you seem to care? What do you do if you are without significant social power or status, and have no platform on which to stand, speak, and be heard? What if your family and close friends think you’re crazy for being so obsessed? And what if there is a war going on in another part of the world that seems to encapsulate and represent all that you hope or fear? While these questions feel all too relevant to our contemporary moment, I’m referring to the Spanish Civil War and the political and cultural crises that accompanied it, which are so powerfully evoked in Sarah Watling’s new book.

In Tomorrow Perhaps the Future, Watling follows a group of mostly women writers and artists whose fears of fascism and fascination with the revolutionary developments in Spain drove them to travel there and report on what they saw—hoping, in the process, to alert the world to the tremendous injustice of western “neutrality.” Spain, of course, turned out to be a dress rehearsal for World War II, with Hitler and Mussolini testing out new military tactics, bombing civilians, and using various terror tactics against supporters of the Republic. The legitimate Spanish government, meanwhile, militarily weakened and abandoned by the western democracies it considered its natural allies, was forced to depend on arms from the Soviet Union and the bravery and sacrifice of rag-tag local militias and, later, the 35,000 volunteers who joined the International Brigades.

Yet many more supporters of the Spanish Republic were not ready to take up arms. What could they do? Scores of writers and artists traveled to Spain to document what was happening, to stir the conscience of the world, and to share in the revolutionary moment. Most of the Spaniards who participated in the revolution, my research shows, would come to see their years of activism as peak moments of their lives: experiences they would not have missed for anything, despite all the hardships, fear, and death. The same seems to be true for the writers and artists featured in Watling’s book, from Martha Gellhorn and Nancy Cunard to Josephine Herbst, Sylvia Townsend Warner, Jessica Mitford, Paul Robeson, and Langston Hughes. They went to Spain to understand, to participate, and to document; and they were profoundly changed by the intensity of political feeling and commitment they experienced there. What Watling writes of Martha Gellhorn could have written of many others: “Because of the war, Martha had got to live the rarest kind of life—a life in which her beliefs and the labors of her days coalesced into a perfect wholeness.”

While the book presents a series of vignettes of individual lives and travels, it also reads as a mystery. Watling tries to reconstruct not just what these artists did, but what they felt—drawing on their published materials and letters, but also on interviews recorded years later. We learn that writers and photographers who were largely ignored in their home countries felt they had a place in Spain. They felt welcomed and valued by those who understood how critical it was to get their stories out to the world. They also came to appreciate the role of culture—the importance of literacy and the value of art—to the revolutionary project in Spain, where levels of illiteracy, especially among women, were very high. There were huge challenges: in addition to the conditions of war, sexism and racism were evident among the volunteers (and also among some of the writers). Most came to question traditional notions of “objectivity,” which, they insisted, made no sense in the context of a war in which right and wrong were so clearly defined. Nevertheless, virtually all continued with their work, putting aside whatever doubts they had about the conduct of the war—or the complex machinations among the Republicans—to try to tell the story of the antifascist struggle for justice.

Watling’s stories resonated deeply with this reader. Our own historical moment feels not all that different from the 1930s: we, too, face world-wide challenges to democracy, a sense that values and practices taken for granted are under threat, and a perception among many that there is “nothing we can do.” But Watling points out that the intellectuals, writers, and artists she studies effectively “made a way out of no-way,” claiming their place in the struggle, and the specific contributions they could make to that struggle as outsiders. Of course, their legacy is a mixed one. They succeeded in stirring the conscience of some but failed to convince the western democracies to intervene on behalf of the Spanish Republic. Still, the images they captured and the stories they told continue to inspire. They also impel us to do what we can.

Martha Ackelsberg is the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor Emerita of Government and Professor Emerita of the Study of Women & Gender at Smith College. Author of numerous works on Feminist Theory, Women’s Studies, and Spain, Ackelsberg’s Free Women of Spain: Anarchism and the Struggle for the Emancipation of Women (1991) is an essential history of women and anarchism in Spain.