Antifascist Resistance: A Dutch Family Saga

After the Nazis occupied the Netherlands, the Seegers family did not hesitate to join the resistance. They had experience fighting fascism: their son Piet had fought for the Spanish Republic. When Tom King started digging into his family history seventy years later, he fell from one surprise into the other.

Southern California, October 2010. My mother, the last remaining member of a notable Amsterdam Communist family, lies dying in the improvised hospice in my parents’ living room in the semi-arid desert east of San Diego. Standing beside her, I watch with clinical detachment as she wearily fills her lungs for what turns out to be the final time. Then, on that final breath, she pronounces a name I have never heard before. I am stunned.

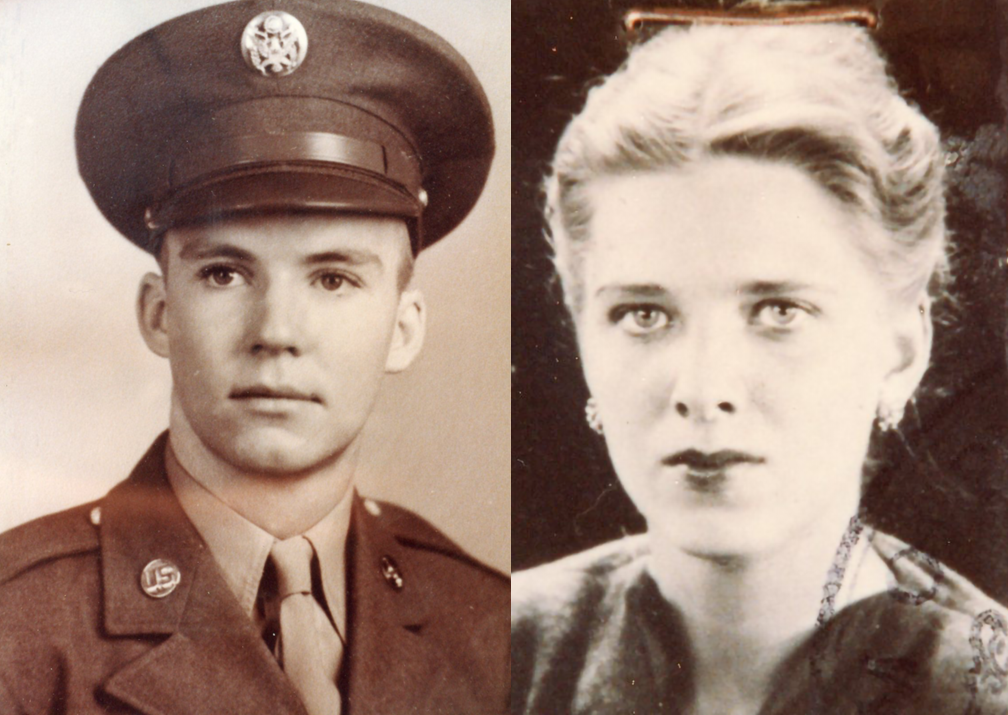

I look around the room seeking an explanation. My father, who as an American G.I. during World War II served as an infantryman under generals like Patton and McAuliffe, tries hard to stare through a blank wall as though it were a pane of glass. My older brother, born in Switzerland while my parents were both students there after the war, gazes down at the floor.

“I think Mom might have had a kid before us,” my brother said later. He also told me that he had a memory of some letters sent to our mother in the 1960s that might have been from the half- brother I never knew existed. He even recalled his full name from a return address he’d seen only once.

In the years following my mother’s death, I managed to gradually put some pieces of the story together. I would learn from my father that when my parents met in their student rooming house in Lausanne (Switzerland), my mom already had a child from a previous marriage. Within a few years, she and my father had one child of their own—my older brother—and she was pregnant with another.

Dad further admitted to me that when they abruptly decided to leave for California, where my American grandmother was dying of cancer, they decided to leave the child from her first marriage—I’ll call him Arend, not his real name—at a children’s home in the Alpine village of Trogen, one of many opened to shelter the vast population of orphans created by the war. My father then took his pregnant wife and child via train, ocean liner, airplane, and automobile to his hometown of San Diego, where they would live for most of the rest of their lives.

But what was Arend’s story? Who was his father, and how had he and my mother met? What had become of him? The answers to these questions, it turns out, seem drawn from the plot of an implausible adventure film that spans the geography of the entire planet, and involves love and war and everything in between. I wonder whether the people who knew my mother in California could ever have imagined the epic scope and sweep of the life of her family. I certainly didn’t.

The story starts with my uncle Piet, my mother’s younger brother, who was one of the roughly 650 Dutch volunteers to join the International Brigades to help defend the Spanish Republic. From the biographical dictionary of Dutch volunteers, I learned that Piet, who had arrived in Spain at the beginning of 1938 and had been taken prisoner by April, spent years in Francoist POW camps like San Pedro de Cardeña and Miranda de Ebro.

Among his fellow captives was a stateless Russian from the Netherlands, Alexis, who had been stripped of his nationality when his father, the Tsar’s ambassador in The Hague, lost his patron in the revolution of 1917. Well-educated, multilingual, and groomed for diplomacy, Alexis was an asset for the prisoners when it came to keeping them mentally engaged with lectures on history and politics, language classes, and chess tournaments. Before pledging himself to the cause of the Spanish Republic, Alexis’s life had been marked by failed business ventures and an unsuccessful arranged marriage to a White-Russian woman of his parents’ choosing.

The stateless Alexis, reportedly with Uncle Piet’s help, was registered as one of the 25 Dutch prisoners in San Pedro. He was also included in a group of four POWs who were released to the Dutch government in December 1939. Meanwhile, the remaining 21 Dutch prisoners, including my mother’s brother, Piet, were sent to Belchite as laborers in the rebuilding of that city, which had been thoroughly razed. Alexis made his way by ship first to England, and then to Rotterdam, before arriving in Amsterdam at the home of Piet’s mother, my grandmother Helena Seegers-Budde, who promptly took him in.

This is when, in a scene worthy of a great Hollywood film, the 33-year-old Spanish Civil War veteran met his host’s 17-year-old daughter, Jet (pronounced in Dutch as “Yet,” short for Henrietta)—my mother—who, within three years, would become his second wife. Jet’s father, the legendary Communist politician Leen Seegers vigorously disapproved of the relationship. But he was in no position to do anything about it, because he was arrested by the Nazi occupiers in April 1941 and deported to the Buchenwald concentration camp, where he was imprisoned until its liberation in April 1945. (After the war, my grandfather Leen resumed his career as an alderman for the Communist Party of the Netherlands in the Amsterdam city council, where he served for forty years.

When he retired in 1967, the city gifted him a trip to spend time with his daughter’s family in San Diego. Although I was only ten at the time, I’ll never forget that visit.)

Meanwhile, as Piet Seegers toiled in Belchite and eventually ended up in Franco’s Miranda de Ebro prison camp, his liberated comrade-turned-brother-in-law Alexis was embarking on a career as a pharmaceutical executive in occupied Amsterdam. It wasn’t long before his young wife, Jet, was expecting a child. Arend was born on May 27, 1942.

Nazi-occupied Amsterdam in 1942 was a chaotic and scary place and time. By the end of October 1940, our maternal grandmother and one of her sons had been arrested for their anti-fascist activities. She was beaten to death in a notorious Hamburg prison while my uncle Leendert was held in a neighboring cell. Leendert was later tried in Berlin on charges of sabotaging German ships loaded with arms for the Spanish Falangists. Improbably, he was acquitted. Nevertheless, he was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where he was deliberately inoculated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a subject in the medical “experiments” conducted by the infamous Zahn brothers. (These Dutch-Nazi quacks and grifters worked under a contract awarded by the buffoonishly self-important Reich Commissioner Heinrich Himmler, whose gullibility the brothers exploited when convincing him of the efficacy of ozone for the prevention and treatment of tuberculosis.) Leendert would eventually die of tuberculosis, aged 29, in the Majdanek Concentration Camp in Lublin, Poland.

Arend, in short, was born into quite a mess. To make things even more complicated, eyewitness accounts of Jet’s life at this time, though few seem to describe an immature, negligent mother who did not take her duties as a wife and homemaker very seriously. Nor did her relationship with Alexis last. At the pharmaceutical company, Alexis met a young secretary, Ann Wagemans, who would later become his third and last wife. When I spoke with Ann in 2012, she told me that it was she, as an early member of the anti-Nazi resistance, who convinced Jet and Alexis to join the underground. Alexis later expressed guilt over not doing so earlier. Jet, who had perhaps enjoyed a maternity-related respite from anti-fascist activism—the Seegers’ “family business,” so to speak—seemed to embrace the sense of obligation provoked by Ann’s example.

Meanwhile… cut, back to Spain… Around the time of Arend’s birth in 1942, the last few Dutch prisoners in Spanish custody, including my uncle Piet, were released from Miranda de Ebro. They were sent first by train to Vigo, Spain, and then by ship via Trinidad and Curaçao to Canada. There, these stateless Dutchmen, stripped of their nationality for the sin of serving under another nation’s flag, were mustered into the Dutch military and trained in various combat specialties. Next, they were shipped to Australia, where they would be pressed into service in the KNIL (the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army). First, they were tasked with defending Dutch Indonesia against the Japanese invaders. Later, they fought against Indonesians who were struggling for independence.

It seems that during this time Piet was captured once again and spent time in a Japanese POW camp. Not long after, we find him back in Australia, where he lived as a refugee and apparently began receiving mental health treatment in a hospital. Meanwhile, his father and sister, Leen and Jet, had lost confidence in the efforts of the Red Cross to find him. They appealed to the Dutch Seafarers Union, hoping it could use its globally distributed membership to find Piet and bring him home. Miraculously, this worked. By late 1945 or early 1946, my mother told me, Piet was allowed to go home.

Cut back to Arend, my long-lost half-brother, who had been born to Alexis and Jet in 1942, and left in Switzerland by my parents after the war: Sometime in 1952, when Arend was ten, Alexis and his wife Ann, who was now expecting a child of her own, withdrew him from the Swiss children’s home where my parents had housed him. They brought him to Brussels, where they lived as a family until moving to Lausanne, of all places, a few years later. While Alexis became quite successful in his career as a pharmaceutical executive, Arend attended an exclusive boys’ high school on Lake Geneva’s south shore, commuting daily via water taxi from Lausanne.

My uncle Piet’s story has a less happy ending. Although my grandfather and mother were able to retrieve him and bring him back to the Netherlands, he would remain institutionalized for the remainder of his life in facilities near Rotterdam, Haarlem, and finally Eindhoven, where he died of chronic illness in October 1963.

Post-script:

In 2011, the year after my mother died, I finally met my half-brother Arend in Amsterdam. We then traveled to Brussels to meet his children and grandchildren, all of whom have by now been melded together with the 45 or so members of the U.S.-based King family to form one exceptional trans-Atlantic clan, united by the struggle against fascism.

Tom King (b. 1957), the son of Dutch resistance fighter Henrietta M. King-Seegers and American veteran-linguist Francis X. King, was born and raised in San Diego, California, and received his bachelor’s and doctorate degrees from UC Berkeley. He lives in San Francisco and is a member of ALBA’s Bay Area community.